Alphonso Gerard

One lone ballplayer from the U.S. Virgin Islands played in the Negro Leagues: Alphonso “Piggy” Gerard, who did so in 1945-48. Thus, when the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Gerard’s honor as a pioneer was amplified.

One lone ballplayer from the U.S. Virgin Islands played in the Negro Leagues: Alphonso “Piggy” Gerard, who did so in 1945-48. Thus, when the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Gerard’s honor as a pioneer was amplified.

The outfielder also played during 14 seasons in Puerto Rico, where a very young Roberto Clemente broke in alongside the veteran. His travels also took him to Canada, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, and he was one of the men whom Branch Rickey considered to break the color barrier before deciding on Jackie Robinson.

Gerard was the sporting hero of a generation of players who grew up on St. Croix, including big-leaguers Valmy Thomas, Horace Clarke, and Elmo Plaskett. As a “bird dog” scout, he started Julio Navarro and José Morales on their path to the majors. This trailblazer shaped the history of baseball in the Virgin Islands.

***

Alphonso Gerard was born in Christiansted, St. Croix, on June 26, 1917, to Benjamin and Louisa Gerard. Like many ballplayers, he shaved several years off his age. Thomas Van Hyning, a historian of Puerto Rican baseball, notes that a recap of the 1953-54 Winter League season says Gerard’s age was 32. However, Osee Edwards of St. Croix, a great fan of Piggy’s as a boy and later a friend and neighbor in Puerto Rico, has helped set the record straight. “Ozzie” was born in 1930, and he reckoned Gerard was about 13 years older. The baptismal records of Christiansted’s Holy Cross Catholic Church confirm it, though Negro League historian Larry Lester’s data show a birthdate of January 22, 1916. (For many other details of this account, thanks also go to Ozzie, who played some ball himself.)

Young Alfonso received instruction in baseball from a Holy Cross priest. Valmy Thomas, Gerard’s teammate for eight years with the Santurce Cangrejeros, remembered Father Meehan. “Though he could not play that well, he taught us well,” Thomas said. “We slept, ate and talked baseball.” Gerard was mainly a pitcher on St. Croix growing up. He admired Dizzy Dean and especially fellow lefty Carl Hubbell. “I was a little boy watching him,” Thomas, 12 years his junior, said. “We used to play on a makeshift field right in Basin.” Their local neighborhood was called Water Gut, for the stream that ran right through their outfield. [1]

As a young adult, Piggy played ball with the local branch of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). His good friend Alfred Thomas, Valmy’s older brother, was a supervisor there. This semi-military organization, which came to the Virgin Islands in 1935 and disbanded in 1941, was enacted with Federal funds during the New Deal. It was designed to train young men and help the community. In Valmy’s words, it “was a place where your parents sent you when you needed some structuring.” [2] Members lived in a camp for two years, learned a trade (for example, carpentry), and earned a salary of $12-$45 a month. The CCC made new roads, planted trees, maintained parks, and so forth. It is easy to see how baseball fit in with its mission.

In 1938, when he was about 21 years old, Gerard moved to Puerto Rico, where he adopted the Spanish spelling of his given name. He represented the island in international competition, but the Cubans got wind of Gerard’s Crucian birth, and he had to come up with a false Spanish-language birth certificate to fend off the challenge. Gerard played amateur ball in the country towns of Manatí and Utuado. Manatí was the hometown of his future boss with the Santurce Cangrejeros, Pedrín Zorrilla. Zorrilla, who was also an executive with Shell Oil, gave Alfonso an extra job as a meter reader.

Piggy graduated to the top local amateur level, AA, where he became the star player/manager for the San Juan Pirates. He broke into the professional winter league with Santurce in 1944. That Crabbers team also included Roy Campanella, but Gerard was co-winner of the Rookie of the Year award with Luis “Canena” Márquez, one of the all-time idols in Puerto Rico. He batted .348 in 141 at-bats and led the league with 12 stolen bases.

This showing impressed Jesús T. Piñero, the first native to be appointed governor of Puerto Rico. During his first season, Alfonso played as an import, though he got only the $25 per week wages of a native rather than the $125 he might have earned. Thanks to Governor Piñero, the league granted Gerard native status. Thus the exemption that would help the next wave of V.I. players was born.

Alfonso’s rookie year also gave him his entrée to the mainland. The Negro Leagues and the Puerto Rican League had virtually shared their blood supply since the latter’s foundation in 1938. George Scales, one of the smartest, toughest men in black baseball history, had been managing the Ponce Leones since 1940. When Piggy went 3-for-4 in his debut against Ponce’s Tomás “Planchardón” Quiñones, the league’s top pitcher and MVP that year, Scales took notice. He brought Gerard up to play with his New York Black Yankees in 1945.

Segregation was then still in force in what were then known as the major leagues. “Blacks had no opportunity, and worse West Indians,” said Valmy Thomas, who reached the majors in 1957. “Anyone who stayed in the oven too long had trouble.” [3] Yet around this time Gerard was apparently an early candidate to cross the line. In the early 1940s, Branch Rickey had instructed Puerto Rican baseball man José Seda to compile scouting reports on every player of consequence on the island. [4] Gerard came to notice not only for his ability but also for his even temperament and clean-living habits (he neither drank nor smoked). However, in interviews with the St. Croix papers, Gerard stated that he was passed over because Rickey wanted an African-American, not — as he mistakenly thought — a Puerto Rican.

In the Negro Leagues, Alfonso “was projected as a deadly hitter and tabbed as a coming star,” [5] but his numbers with the Black Yankees were unexceptional. He batted .258 in 1945. In 1946, Gerard became one of the many players whom Mexican baseball magnate Jorge Pasquel lured south of the border in his abortive bid to create a major league. Along with several Negro League compadres, he joined the new franchise in San Luis Potosí. With the Tuneros (translation: Prickly Pear Pickers), he hit .261 in 40 games. One of the Pasquel brothers gave him a solid gold watch.

Gerard returned to the Black Yankees in 1947, but after a slow start, he went to the Indianapolis Clowns. There he performed his best as a Negro Leaguer, hitting .340. Moving to the Chicago American Giants in 1948, he posted an average of .262. Piggy had a reputation for handling the best fastball pitchers, such as Satchel Paige. He once tripled off Satch to lead off an inning, but the master told him, “You aren’t going anywhere,” and proceeded to strike out the side.

Alfonso played with the Clowns again in 1949, but as the signing of Jackie Robinson heralded the decline of the Negro Leagues, a good many black ballplayers found work in Canada, which had integrated earlier and was generally a much more receptive environment. Gerard was with two clubs in 1950. He hit .333 for Kingston (Ontario) of the Colonial League, and when that league disbanded in July 1950, he hooked on with Pittsfield (Massachusetts) of the Canadian-American League, where he hit .258. He then spent two seasons in the Canadian Provincial League, batting .337 for Three Rivers and .303 for Granby, both in Québec. If the weather got too cold for his liking, he would wear a catcher’s chest protector as an extra layer!

In 1953, Piggy went to play for the summer in the Dominican Republic. Pro ball had resumed there in 1951 but did not switch over to the winters until 1955. He was with the Escogido club in Santo Domingo that season, facing Valmy Thomas, who was with arch-rival Licey.

All along, Alfonso had been playing for Santurce during the winters. He registered some very fine averages, especially as a regular from 1947-48 through 1951-52, batting in the #3 spot ahead of Willard Brown. His best mark, .342 in 1948-49, was good enough for fourth in the league. Freddie Thon Jr. — the father of future big-leaguer Dickie Thon — called Piggy “a pesky hitter who could hurt you.” Thon told author Tom Van Hyning that Willard “Ese Hombre” Brown and Bob “El Múcaro” Thurman “were the big guns, but that Gerard did a lot of damage to opposing teams throughout his Santurce career.” [6]

Gerard’s lifetime batting average of .303 (with just six homers) stands eighth on the all-time list in Puerto Rico. He played on three champion clubs with the Cangrejeros, all of which also won the Caribbean Series, including the Scales-led 1950-51 group. Another Negro Leaguer, Buster Clarkson, was player-manager of the 1952-53 team. Gerard went 1-for-3 in the 1951 series, as Luis Olmo joined Brown and Thurman as the starting outfielders. In 1953 he was 3-for-5 with a triple; that year Canena Márquez started ahead of him. [7]

Most noteworthy of all, though, was the 1954-55 squad, which Don Zimmer called “the best winter league baseball club ever assembled.” [8] Managed by Herman Franks, the cast again featured Latinos, Negro Leaguers, and both black and white major leaguers. Willie Mays formed an extraordinary outfield with Thurman and Clemente, but reserve Gerard chipped in with 28-for-84 (.333). His big moment in the Caribbean Series came in Game 4, as the Crabbers came back from a 6-0 deficit to beat Almendares of Cuba. Down 6-4 with two out in the 9th, Alfonso singled to left as a pinch-hitter. Zimmer homered to tie the game, and then Clemente walked and came all the way around on a Mays single. [9]

Alfonso Gerard ended his playing career in 1957-58. If there is any apt major-league comparison in more recent times, it might be Greg Gross, another outfielder who hit for high averages with very occasional power. Both also had good batting eyes, striking out about half as much as they walked, although the Puerto Rican statistics from that time are patchy. While Gross drew more walks, Gerard had better speed and range and also served as an infield fill-in in the Negro Leagues.

Before his retirement, Gerard received an offer to return to Canada to teach children to play ball. [10] Instead, he returned to St. Croix, where he managed local teams and was in charge of development and maintenance of fields for the V.I. government’s baseball development program. He was also a bird dog for Santurce owner Pedrín Zorrilla, who himself scouted for the Giants. Zorrilla signed Julio Navarro in 1955 and José Morales in 1963.

Piggy wanted to see more locals succeed. “His son James ‘Tremelle’ Gerard said his father would get disappointed when he heard about young players who forfeited good careers because they lacked the discipline to live out the sport. ‘My father felt there were a lot of guys that left here and could have made it. It would break his heart’ when they ended up coming back home.” [11]

Outside of work, Valmy Thomas remembers that “Gerard had a lot of goats at one time. Goat milk and cognac, that was his concoction. People would flock around his car when he would open his trunk, they would get in line!”

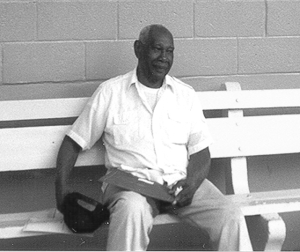

Gerard retired in 1984 and lived for the next 18 years outside of Christiansted. His humble white concrete home in the Estate St. Peter’s neighborhood was just half a mile over the hill from David C. Canegata Ballpark, where he had spent much time at work. For several years during his time in Puerto Rico, Gerard was apparently married, but even his own sister and Valmy know little more.

Gerard suffered a mild stroke in 1998, and his memory loss deprived us of more personal reminiscences. For the next year at least, he still spoke clearly and moved around unaided. He enjoyed sitting peacefully outside with his two dogs, and he remained well enough to cut the ribbon at the ceremony for the Basin Triangle residential community that was named for him in July 2001.

Gerard suffered a mild stroke in 1998, and his memory loss deprived us of more personal reminiscences. For the next year at least, he still spoke clearly and moved around unaided. He enjoyed sitting peacefully outside with his two dogs, and he remained well enough to cut the ribbon at the ceremony for the Basin Triangle residential community that was named for him in July 2001.

Gerard’s health gradually declined, though, and the old outfielder finally passed away on July 14, 2002. According to his obituary, he had been suffering from Alzheimer’s and prostate cancer. He was survived by his daughter Linda and sons James and Antonio. [12]

Valmy Thomas recalled, “I last saw him two or three months before. After that he went into the hospital. It was too hard for me to see him, who had been such an active man, in such condition. I read the eulogy, I recounted some of the things I knew about the Negro Leagues. He was the quiet one, I was the loud one. Translated: I spoke my mind! The bus life, barnstorming, waiting in back of the restaurants — not for me, no way, José!” But without Alfonso Gerard’s trailblazing, the opportunity for Thomas and all the other Virgin Islands ballplayers might never have arisen.

Sources

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, PR: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Acknowledgments

This biography originally appeared on the now-defunct website “Baseball in the Virgin Islands,” from which it was adapted. It was most recently updated on June 17, 2025.

Grateful acknowledgment to Osee Edwards and Valmy Thomas for their personal memories of their friend, Alfonso Gerard.

Photo Credits

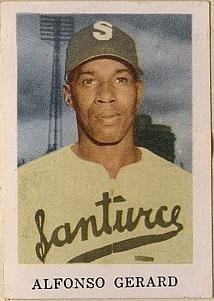

Baseball card from 1950-51 Toleteros Puerto Rican set.

Gerard in 1999: taken by the author on St. Croix.

Notes

[1] Karen D. Williams, “Memories Are Many of Alphonso ‘Piggy’ Gerard,” St. Croix Source (online newspaper), July 18, 2002.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 56.

[5] James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers), p. 312.

[6] Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999), p. 28.

[7] Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2005), pp. 346, 374.

[8] Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1995), p. 216.

[9] Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, p. 70.

[10] Williams, op. cit.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

Full Name

Alphonso Gerard

Born

June 26, 1917 at Christiansted, St. Croix (VI)

Died

July 14, 2002 at Christiansted, St. Croix (VI)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.