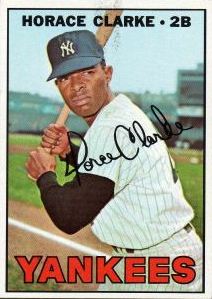

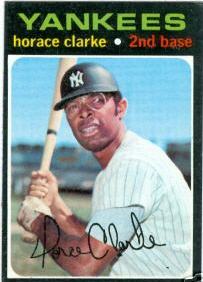

Horace Clarke

He was a leadoff man. He played all through the eclipse of baseball’s greatest franchise. So, mainly for worse he came to symbolize an era. Alas, Horace Meredith Clarke was never a star, but he was a pesky hitter with speed and a good glove. Perverse as it may be, his durability and visibility made Horace the undeserving scapegoat for the Roman Empire-like dry rot of the Yankees after 1964. This descent was exposed through the neglect of the CBS ownership. The criticism of sportswriters and fans, many of whom had a sense of entitlement, bothered him at the time. “But now that I’m through playing,” said Clarke in 1999, “my conscience is clear.”

Horace was the fifth of 16 men (as of 2020) from the U.S. Virgin Islands to make the major leagues. He was born to Dennis and Vivian Woods Clarke in Frederiksted, St. Croix, on June 2, 1939. During his career, his published year of birth was 1940, but the 1940 census shows him in Frederiksted with his age listed as one.

“Harry” — as he remained known at home — was the youngest of six children. There was one brother named Verne and four sisters named Dina, Holly, Annette, and Letty.

Dennis Clarke was a cricketer. He saw a curveball for the first time from a Navy sailor but decided he “was too old to learn a new game.” He also played the violin, and his son inherited the musical inclinations. “I don’t know whether baseball gained or music lost,” said Horace in 1969.1

At the time, there were no Little Leagues on St. Croix, so the boy’s introduction to the game came via softball. At age 13 or so, he remembered seeing Navy ship’s teams playing hardball against the locals at Frederiksted’s Paul E. Joseph Stadium. “As kids we formed teams and played wherever we could, usually on Saturdays. If the older players were using the ballpark, we were relegated to a small area by the ocean.”

“Almost all of us were right-handed. And since we were strong enough to hit the ball into the water, we switched sides at the plate, and everybody batted left-handed, so we wouldn’t lose the ball.”2

Horace joined the Braves, a local team in the St. Croix Baseball League, which was made up mainly of teenagers with some adults. He played there for five years, also representing Christiansted High School in inter-island school meets against St. Thomas (whose teams featured future Orioles catcher Elrod Hendricks). His coach was math teacher David C. Canegata, for whom the other main ballpark on St. Croix is named.

Clarke remembered attending the 1957 tryout camp where Pittsburgh superscout Howie Haak signed his fellow Frederiksted native, future Pirate Elmo Plaskett. As he noted in 1999, though, “it just wasn’t my time yet.” But the next year he turned pro at the age of 18. Yankees scout José “Pepe” Seda, who contributed to the Puerto Rican Winter League on many levels, signed him that January. It was at that time that Clarke shaved a year off his age, on Seda’s advice.3

The young Crucian made his pro debut in 1958 with Kearney of the Nebraska State League. It took a season to adjust — to night ball, among other things. Clarke batted just .225 in 187 at-bats, with 2 homers and 20 RBIs. However, he showed off his most valuable attribute — speed — with 27 stolen bases.

Clarke’s marks then picked up to 5-58-.292 for St. Petersburg in the Florida State League in 1959. He added 34 steals. In 1960, he followed with 2-40-.307 for Fargo in the Northern League, swiping 22 bases. He made the circuit’s All-Star team at shortstop and moved up to Single-A Binghamton for a game at the end of that year. Staying with Binghamton in 1961, he led the Eastern League with 40 steals (3-38-.278).

As it did for so many players, including other men from the Virgin Islands, the Puerto Rican Winter League spurred Clarke’s development. He felt that hitting against pitchers such as Bob Gibson, Earl Wilson, and Denny McLain really sharpened his skills on the way to the big leagues.4 Clarke began his winter ball career in the winter of 1959-60 with the San Juan Senadores. His father asked José Seda to arrange this opportunity. As a backup to Jerry Adair and local favorite Ronnie Samford (a Texan who played on the great Santurce Crabbers teams in the mid-fifties), he hit .247 over his first three seasons.

The oceanside sandlot training from Frederiksted also reasserted itself. “It was the winter of 1960 when I began to fool around as a switch-hitter in Puerto Rico. I did pretty well with it, so [with the support of manager Jimmy Gleeson] I kept doing it in Binghamton…and have been switching ever since.”5

Clarke roomed for a couple of winters at the San Juan YMCA with his friendly rival from St. Thomas, Ellie Hendricks. Although they were rarely around at the same time, owing to the schedule, they still became close. Hendricks recalled that musical Horace, “who hardly said anything,” played vibraphone and xylophone.

During the 1962-63 season, at Elmo Plaskett’s urging, the Ponce Leones traded for the infielder. Either Al McBean from St. Thomas or Clarke formed a Virgin Islands tandem with Plaskett for several winters in Ponce. However — mainly because Pittsburgh had McBean sit out that PRWL season and the next — the whole trio was on the field together just briefly, in 1964 before Plaskett suffered a broken leg.

Clarke also benefited from the Puerto Rican culture. He had grown up hearing a lot of Spanish spoken on St. Croix, but had never picked up more than a few words. But like Plaskett, McBean, and Joe Christopher, he met his wife in Puerto Rico, and so he had a reason to learn. A San Juan girl, Hilda Robles was a little put out with Elmo — even though she was very fond of him — for making her ride two hours to Ponce! Horace and Hilda eventually got married in October 1966.

Back stateside, the unsung farmhand continued his steady progression in the minors, hitting .300 with 9 home runs, 50 RBI, and 17 stolen bases for Double-A Amarillo in 1962. Earning promotion to Triple-A Richmond the next year, his totals dipped to 4-26-.249, with a mere 6 steals. However, he lifted that to 5-44-.299 in 1964, back in Richmond, also rebounding to 20 stolen bases. After starting the year at Toledo (which had replaced Richmond as the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate) in 1965, he broke in with the Yankees that May as a utility infielder. He singled off Dave Morehead in his debut at Fenway Park on May 13, pinch-hitting for Hal Reniff.

Clarke spent the months of May and June with the Bombers and then returned to Toledo for the next two months before being recalled in September. Overall, he finished 2-32-.301 in 89 games for the Mud Hens and 1-9-.259 in 51 games for the Yankees. A special highlight came at Yankee Stadium on September 21: his first major-league homer, off Cleveland’s Floyd Weaver, was a grand slam.

When the wheels came off in ’66, with the Yankee franchise finishing last for the first time since the 1912 Highlanders, starting in July Clarke got a chance to play every day. “Rubén Amaro had a major injury and they were looking for shortstops within the troops. Ralph Houk said, ‘You’re going to be the shortstop the rest of the year. Bobby Richardson is going to retire in the coming year or so and you’re going to be the second baseman, we hope. So I want to see how you handle the bat.’”

With Richardson’s retirement after the 1966 season, The Major did in fact install Clarke as the regular pivotman in 1967. On March 31 that year, he enjoyed a celebration at Paul Joseph Stadium as the Yankees beat the Red Sox in the first major-league exhibition game ever in the Virgin Islands.6 The man who set up the event was the first big-leaguer from the territory, Valmy Thomas, then a sports consultant with the St. Croix Bureau of Recreation.

Clarke went on to record what would be a pretty typical season for him: 160 hits in 588 at-bats (.272) over 143 games, with 21 steals. A note of interest: his second big-league homer (at Knasas City on July 16) was also a grand slam. However, the winter of 1967-68 would be his last in Puerto Rico — the Yankees asked him to stop playing there for fear of injury or overwork.

“At first I said, ‘Well, wait a minute now. That’s my winter earnings that’s going down the drain there, will you consider subsidizing me for not playing?’ The first year they did, but after that, I guess getting that year off, somehow or the other I might have liked it, because I never went back. And I had lodged a part-time job on St. Croix giving clinics, after-school sessions which I got a couple of bucks for.”

Clarke had been a starter with Ponce for five years, batting .281 overall and leading the league in triples and runs scored as an All-Star in 1965-66. He was an All-Star again the next winter — at shortstop. Over his ten seasons in Puerto Rico (1958-59 through 1967-68), Horace recorded 12 homers, 140 RBIs, and a .270 average in 1,835 at-bats. He added 52 steals and 25 triples.

After an off year in 1968 (.230 with just nine extra-base hits), Clarke’s strongest offensive season came in ’69. He hit a career-high .285 with an on-base percentage (OBP) of .339 and 33 steals. The next year also had some career moments. On April 19, 1970, Clarke enjoyed a five-hit day in the nightcap of a doubleheader at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. In the span of a month, he also broke up three possible no-hitters in the ninth inning, foiling Jim Rooker on June 4, Sonny Siebert on June 19, and Joe Niekro on July 2.

It’s worth noting that the Yankees of this era were not always bad. The 1970 Yankees won a very healthy 93 ballgames, but they were simply outclassed by the Orioles, who finished 15 games ahead. In addition, the ’72 club was one of four AL East contenders into mid-September before falling out of the race.

But in 1974 — the second year of George Steinbrenner’s ownership — Yankees general manager Gabe Paul continued to clean house. Clarke was dealt to San Diego in May for $25,000 in cash. As it turned out, the bridge to Willie Randolph at second base was a former double-play partner in Ponce, Sandy Alomar Sr. — who would later do the Clarke family a good turn. Horace played in 42 games for the Padres and retired after that season. His final major-league totals were 27 homers, 304 RBIs, and a .256 batting average, plus 151 stolen bases.

In summary, Clarke’s career may not have been stellar, but it was quite admirable. He appeared in the most major-league games (1,272) of any player from the Virgin Islands, though his career on-base percentage of .308 was less than ideal in the leadoff slot. As a contact hitter and deft bunter, perhaps he would have been best off hitting second.

A sounder choice at the top of the lineup would have been Roy White — .360 career OBP, consistently ranging from .380-.400 from 1969-72, and also a good base stealer (though Clarke’s 72% lifetime success rate was better than the left fielder’s 67%). Ralph Houk recognized this, but argued, “I can’t spare [White] up there because he’s my big RBI man.”7

Years later, The Major remarked, “I know I got a lot of criticism for playing Horace Clarke as much as I did, but he was a lot better ballplayer than anyone gave him credit for. He did a lot of things good but nothing great, and that was his problem. . .besides, I didn’t have anyone else.”8

Clarke made a similar comment in 1999. “I was just one little infielder, one of 25 guys, not any Superman.” But he added, “After all the negative ink, after I got out of the game, I said, ‘Let me see what my accomplishments were.’” In retrospect, he regarded himself as an underrated defensive player.

There was one big knock on him in the field, though. It wasn’t so much that he wore his helmet — he would not turn the double play with runners barreling in. Nobody ever took out Clarke with a slide, but he held the ball after leaping. Several members of the sinkerballing Yankees staff, “who lived and died on ground balls. . .confronted their teammate. ‘It was a sore subject with him,’ says [reliever Jack] Aker, ‘and he became upset.’”9 The late New York sportswriter Dick Young, curmudgeon par excellence, also took Clarke to task for this shortcoming in his usual brusque manner.

But another NYC columnist, Phil Pepe, was a more generous sportsman. When Clarke left the Bronx, Pepe wrote, “You know what, there are a lot of good things to say about Horace Clarke. And the more I poked around, the more good things I found to say about him. If you went to him with a fair question, he’d give you an honest answer, and if you met him in a hotel lobby, he’d nod or say hello even if you’ve been knocking his brains out for years. It takes a man to do that.”10 Thirty years later, Pepe again rose in support of Horace in a piece called “Enough of the Clarke bashing”.11

Cecil Harris, who became the first Black beat writer to cover the Yankees in the 1990s, sounded the same theme. Harris, whose parents came from Barbados, grew attached to the Virgin Islander as a young fan. He chose as his hero “a guy in whom I saw a semblance of myself.” Over several pages in his book on the Bombers, he too made a spirited defense of his boyhood favorite. Harris even argued that the gulf between Clarke and Willie Randolph was not so great, and that the 1977-78 champions could just as well have won with Hoss.12

Perhaps even more noteworthy was how Horace’s conduct under the critics’ barrage formed future Yankee captain Thurman Munson’s avoidance of the press. Munson added a curious footnote on team history. “Polite and humble Clarke was a hard-working family man. . . the last club member, according to Thurman, to make his residence in the direct vicinity of Yankee Stadium.”13

Horace Clarke’s two sons each played in the minors. Jeff Clarke (2B/SS) signed as a free agent with the Royals in 1991. After two years of A ball, he was derailed by injuries, though he was considered as a replacement player by Kansas City in 1995. Jason (J.D.) Clarke, also a middle infielder, enjoyed a successful college career at St. Thomas University in Miami, Florida. He was named Florida Sun Conference Player of the Year in 1998. The Cubs signed him as a free agent on the recommendation of scout Sandy Alomar, Sr., and J.D. played 1999 and part of 2000 in Single-A.

After his playing career was over, Clarke returned to St. Croix, teaming with Elmo Plaskett as a government-paid instructor in the local baseball programs. They reported to Valmy Thomas, who’d risen to Deputy Commissioner in the Recreation department. Another colleague was Alfonso Gerard, St. Croix’s pioneer in the PRWL and Negro Leagues. “Piggy” — who was Horace and Elmo’s sporting hero and Valmy’s longtime teammate — was in charge of field development and maintenance. It was hard, hot work, but they did it for love of the sport and their desire to see young people do well. Their star pupils were Jerry Browne, who went on to play from 1986 through 1995 in the majors, and Midre Cummings (1993-2001; 2004-05).

For several years in the early ’80s, Clarke was an associate scout with the Kansas City Royals after meeting one of their people at a tournament in Panama for the 13-15 age group. “It’s now a fancy name for a bird dog,” he said. “You can make a reference or recommend, but you’re very limited in signing a player.” Clarke had entertained the idea of getting back into the majors as a coach, but found that attending minor-league camp with the Royals was quite satisfying because the young players were keen to hear his advice. He was also interested to see how much training methods had changed since his time.

Clarke took an early retirement package in 1997. The Virgin Islands haven’t been producing as many major-leaguers as they used to, and while there are many reasons — basketball, immigration, politics, television — the absence of Clarke and Plaskett (who passed away in 1998) made a difference at the grassroots.

The key issue — anywhere, not just the V.I. — is what happens to players once they hit their teens. Clarke called it “the real test, the real keeping of the nose to the grindstone. There’s practice, there’s regimentation. When that kid gets about 13 or 14 years, he says, ‘Man, I’m tired of this crap. I could go to the beach, I could go fishing, and have more fun than to have somebody bawling down my ears.’ And let’s face it, baseball is supposed to be a game and to be fun. It doesn’t come to be fun when you got a manager saying, ‘You gotta do this, you gotta do that’ — but you gotta do it!”

Yet still, Clarke believed there will always be a select few from the Virgin Islands who are willing to work and do what it takes. He took a quiet pride in his homeland and its baseball tradition.

In his late sixties, Horace underwent several operations (heart, hip, knee), but it helped that there still wasn’t one excess pound on his frame. He enjoyed the quiet life in Frederiksted — unlike chatty Al McBean, he didn’t even have a phone. He liked to rise early and practice his music, playing vibes in a local jazz combo. He also went back to Yankee Stadium for quite a few Old Timers’ Games over the years, most recently in 2013. When asked after the 2002 edition why he didn’t play, the old second baseman replied, tongue firmly in cheek, “It’s time to give way to another generation!”14

On September 5, 2007, the Yankees invited Horace up once more for a special on-field appearance as part of a co-promotion with the Virgin Islands government to boost tourism in the islands. Many fans and writers would do well to emulate the organization’s quiet and enduring loyalty to this player. Indeed, there was a shift in the tone of stories about Clarke from the new millennium onward, especially toward the end of his life.

Owing to complications from Alzheimer’s disease, Clarke died on August 5, 2020, at the home of his son Jeff in Laurel, Maryland.15 His passing prompted an outpouring of warm memories in the media and from many friends.

Acknowledgments

This biography originally appeared on the now-defunct website Baseball in the Virgin Islands, from which it was adapted. Grateful acknowledgment to Horace Clarke for providing his memories (personal interview on St. Croix, 1999), to his late wife Hilda, and to his son J.D.

All Clarke quotes come from the 1999 interview, unless otherwise indicated.

Sources

www.retrosheet.org

Professional Baseball Players Database

Private database of José Crescioni (Puerto Rican statistics)

Notes

1 Jim Ogle, “Musician Clarke Playing Hot Yank Tune With Glove, Bat,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1969.

2 Philip Bashe, Dog Days: The New York Yankees’ Fall from Grace and Return to Glory, 1964-76, New York: Random House, 1994: 106-107.

3 E-mail from J.D. Clarke to Rory Costello, June 2, 2020.

4 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995: 105.

5 Ogle, “Musician Clarke Playing Hot Yank Tune With Glove, Bat/”

6 Dave Anderson, “Yankees Top Red Sox, 3-1; Clarke Is Hailed in Virgin Islands,” New York Times, April 1, 1967: 22.

7 Phil Pepe, “Houk Man of Letters, Mostly Clarke Critics,” New York Daily News, September 1, 1970: C22.

8 Bill Madden, Pride of October, New York: Warner Books, 2004: 187.

9 Bashe, Dog Days,: 202-203.

10 Phil Pepe, “Is Obit Needed as Clarke Goes?” New York Daily News, June 3, 1974.

11 Phil Pepe, “Enough of the Clarke bashing,” Special to YES Network Online, August 31, 2004.

12 Cecil Harris, Call the Yankees My Daddy, West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Infinity Publishing, 2005: 14-17.

13 Christopher Devine, Thurman Munson: A Baseball Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001: 37.

14 Phone call, Rory Costello with Horace Clarke.

15 E-mail from J.D. Clarke to Rory Costello, August 5, 2020.

Full Name

Horace Meredith Clarke

Born

June 2, 1939 at Frederiksted, St. Croix (V.I.)

Died

August 5, 2020 at Laurel, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.