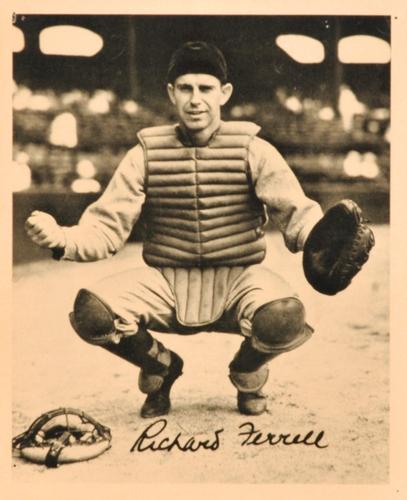

Rick Ferrell

Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell (1905-1995) caught in the American League for eighteen years (1929-45,’47) during two of America’s most challenging periods: the Great Depression and World War II. Playing for the St. Louis Browns, Boston Red Sox, and Washington Senators, his skill as a durable knuckleball catcher with a laser-accurate arm for picking off potential base-stealers was held in high regard. His .378 career on-base percentage is eighth all-time among 50 catchers with 3,000 at-bats, and fourth among the thirteen major league Hall of Fame catchers, bested only by Mickey Cochrane (.419), Roger Bresnahan (.386), and Bill Dickey (.382).

Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell (1905-1995) caught in the American League for eighteen years (1929-45,’47) during two of America’s most challenging periods: the Great Depression and World War II. Playing for the St. Louis Browns, Boston Red Sox, and Washington Senators, his skill as a durable knuckleball catcher with a laser-accurate arm for picking off potential base-stealers was held in high regard. His .378 career on-base percentage is eighth all-time among 50 catchers with 3,000 at-bats, and fourth among the thirteen major league Hall of Fame catchers, bested only by Mickey Cochrane (.419), Roger Bresnahan (.386), and Bill Dickey (.382).

Richard Benjamin Ferrell was born on Columbus Day, October 12, 1905, in Durham, North Carolina, the fourth of seven sons of parents Rufus and Alice Ferrell. Rufus had enjoyed playing sandlot baseball, passing his passion on to his sons, who grew up playing the game together out on the homemade baseball field at the family’s 160-acre dairy farm near Greensboro. Six sons fancied themselves as pitchers, with Rick as the catcher who caught them all by the hour. Primarily self-taught, they played on high school and North Carolina county league teams during their teen years. Rick, Wes, and George ultimately developed lifelong careers as a major-league catcher, pitcher, and minor-league outfielder, respectively.

Despite his slender build, at an early age, the quiet, hard-working Rick secretly aspired to become a professional baseball player and devoted all his efforts towards achieving that goal. From 1923-26, the 5’10”, 160-pound athlete attended Guilford College, locally, where he lettered in both baseball and basketball and received top coaching. To pay for classes, the muscular Rick boxed in county middleweight boxing matches, winning 18 of 19 bouts he fought.

In 1926, the Detroit Tigers signed Rick for $1500. After three years in the minors, (Kinston, then Columbus) in 1928, Ferrell hit .333 and made the league All-Star squad, despite being on a seventh place team. After failing to be called-up to the majors in September, the catcher suspected that he was being unfairly buried in the minor leagues, a common, though illegal practice at the time. At the end of the season, a determined Ferrell traveled to Chicago to request free agency from the Grand Wizard, himself: baseball commissioner Judge Landis. After learning that the Columbus club and its players’ contracts had all been secretly sold to the Cincinnati Reds the previous off-season, Landis agreed that the catcher was being illegally held back and granted him free agency. After sorting through multiple, immediate offers from eight major league teams, Ferrell signed a three-year contract with the St. Louis Browns that included a $25,000 bonus—one of the largest ever awarded a baseball player at that time—which Rick promptly turned over to his father to help pay for the farm.

Browns manager Dan Howley debuted Ferrell, 23, vs. the Chicago White Sox on April 19, 1929, as back-up catcher to veteran Wally Schang. Rick got his first hit in his next game. The motto for the Browns was “First in shoes, First in booze, and Last in the American League;” the St. Louis Browns placed fourth, sixth, fifth, and sixth from 1929-32, despite having Ferrell, pitcher General Alvin Crowder and slugger Heinie Manush on the team. Ferrell’s first year was his weakest, as he hit only .229 in 64 games as second-string. For the next three years as starting catcher under manager Bill Killefer (1930-32), Ferrell played in over 100 games per season and dramatically raised his batting average to .306 in 1931, becoming one of the premier receivers in the league.

On April 1, 1932, Browns coach Allen Sothoron told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I don’t think there’s a better catcher in baseball. I had heard and read a lot about [Ferrell], but he was really better than I believed he could be.” By the end of the 1932 season, Rick hit .315, the best among American League starting catchers, with 30 doubles and 65 runs-batted-in, while defensively, he had totaled 78 assists, second highest of any AL catcher.

From 1929-32, Rick’s younger brother, right-hander Wes Ferrell, had gained instant major league success as a pitching ace for manager Roger Peckinpaugh’s Cleveland Indians. The only pitcher since 1900 to win 20 or more games in his first four years, Wes had won 21 games in 1929, 25 in 1930, 22 in 1931, and 23 games in 1932 while power-hitting home runs, as well. With 38 career homers, he is still often considered the best hitting-pitcher of the twentieth century.

“We were brothers off the field, but there was no love lost on it,” Rick said. “We fought like cats and dogs. Wes was always trying to strike me out, and meantime, I was always trying to hit a home run off him.” As evidence, on April 29, 1931, Wes pitched a 9-0 no-hitter vs. the Browns that was almost broken up by his brother Rick, who blasted a hit through the middle that the scorer ultimately ruled an error on a wide throw from short to first base.

During the 1930s, Rick became one of several major league catching stars that included Mickey Cochrane, Bill Dickey, Al Lopez, Ernie Lombardi, and Gabby Hartnett. On May 10, 1933, young Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey purchased Ferrell from the fiscally strapped Browns with southpaw Lloyd Brown for catcher Merv Shea plus cash estimated at between $50,000 and $100,000. From 1929-early 1933 with the Browns, Rick had hit .289 in 430 games.

With the east coast Boston Red Sox, the catcher enjoyed his best years, catching and hitting well. Two months later on July 6, 1933, Connie Mack chose Rick to catch the entire inaugural All-Star Game. The American League team, consisting of such luminaries as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Al Simmons, Charlie Gehringer, and Lefty Grove, beat the National League, 4-2. Rick was selected to a grand total of eight All-Star teams (1933-38, 1944-45; no game in 1945 because of wartime travel restrictions).

When Cleveland and his brother Wes played against Boston two weeks later on July 19, 1933, Rick homered off Wes, after which Wes homered off Boston’s Hank Johnson, marking the first time brothers on opposing teams had homered in the same game. They taunted each other about their home runs during the game and went out for a steak dinner afterwards. Rick caught a career-high 137 games in 1933.

Yawkey was trying to buy a pennant-winning team, which eluded him. In 1934, due largely to Rick’s encouragement, Yawkey and Eddie Collins signed the ailing Wes to a Red Sox contract, creating the historic Ferrell brothers battery for the next three and a half years (1934 until mid-1937) under managers Bucky Harris and Joe Cronin. While extremely close, the Ferrell brothers presented a study in contrasts. In appearance, Rick was slightly balding with dark hair, slim and muscular, and looked like a banker or college professor; big Wes, 6’2”, and 35 pounds heavier at 195 lbs., was movie-star handsome with thick wavy, blonde hair and a big smile. Older by two years, Rick displayed a quiet, mild-mannered temperament while Wes could be brash and outspoken. Rick was a model teammate, a leader by example, considerate and helpful to others. Wesley was a hothead, at times, acting impulsively out of frustration and a strong desire to win. But while supremely competitive against one another on the field, off the field the brothers were extremely loyal, roomed together, and got along well. Speaking of Rick, Wesley observed, “Brother or no brother, he was a real classy catcher. You never saw him lunge for the ball. He never took a strike away from you. He’d get more strikes for a pitcher than anybody I ever saw because he made catching look easy.” In 1934, Rick led all American League catchers with a .990 fielding average in 128 games and was selected for the All-Star team, as Wes garnered a 14-5 record.

A strong contact hitter, the catcher developed a pattern of hitting in the .300’s during the season until September, when due to exhaustion and the wool uniforms in the summer heat, his batting average would invariably drop. Yet he still hit over .300 five times during his career.

In 1935 with Rick as his catcher and personal confidante, Wes pitched a 25-14 comeback season, using his “nuttin’ ball,” to compensate for an over-worked, lame arm. The pitcher hit .347 and was voted runner-up to league MVP Hank Greenberg. Boston’s “Lefty” Grove went 20-12. Rick got 138 hits for a .301 season and was selected to the American League All-Star team. In 1936, Rick hit for a .312 average in 121 games behind the plate and was again selected for the All-Star Game, but Boston placed sixth (74-80) in the standings. During an August game, the Ferrell brothers became embroiled in an embarrassing, volatile argument with umpire Lou Kolls, leaving the duo temporarily suspended and Red Sox management upset.

The following June 10, 1937, as Rick was batting a strong .308, he and Wes were unexpectedly traded together with Mel Almada to the Washington Senators for pitcher Bobo Newsom and outfielder Ben Chapman. (Washington’s Clark Griffith would only make the deal if Rick was included.) Totaling a .302 batting average from 1933-37 with Boston, Rick had broken Red Sox catcher’s records in batting, home runs, doubles, and runs-batted-in.

With the Senators, Rick and Wes again formed a battery under manager Bucky Harris and both were selected for the 1937 AL All-Star team. In a season of double-injuries, Rick hit a mere .244 in 104 games, playing the season with a partially broken right hand while gripping the bat with his single, left hand at the plate. Playing through the pain, he never once asked to come out of the lineup. Wes went 14-19 for the season, but was released in August 1938 (13-8). As his battery mate for five years, Rick had caught 141 of his starts, including nine shutouts.

In 1938, Rick topped all catchers at starting double plays with 15. Also in 1938, he first began successfully catching the Senators’ big knuckleball pitcher Emil “Dutch” Leonard, giving Leonard a new chance in the major leagues. By 1939, Leonard became a 20-game winner, success he attributed to having a catcher like Ferrell, who could handle the knuckleball pitch.

The Senators played at Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939, when Lou Gehrig retired from baseball with his “Luckiest Man” speech. Rick was standing three feet from the microphone and always clearly remembered that day. When Ted Williams once asked Ferrell how to pitch to Gehrig, Ferrell replied, “No one way. You’ve got to move the ball around, try to cross him up and outguess him…keep him off-stride.”

In 1940, Ferrell caught 99 games for Washington for a .980 fielding average and a .273 batting average. Yet even with Ferrell, Buddy Lewis, Cecil Travis, Sid Hudson and Mickey Vernon on the team, the Senators finished in the second division during Rick’s tenure.

On May 15, 1941, three months after he married Ruth Virginia Wilson, the catcher, 35, was traded back to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Vern Kennedy. Rick caught 98 games for pitchers like Denny Galehouse, knuckleballer John Niggeling, and Elden Auker.

In a clutch situation, Ferrell almost always seemed to belt the critical hit with the game on the line. On September 26, 1941, his bunt single in the fifth inning broke up Bob Feller’s no-hitter in a 3-2 St. Louis loss, but the Brown ended in sixth place, 70-84, exactly tied with Rick’s former team, the Washington Senators. On December 7, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor led to the US entry into World War II, as wartime baseball and player depletion began.

In 1942, Ferrell, now 36, caught 95 games, sharing catching duties with Frankie Hayes, to help the Browns finally finish in third place—a team that hadn’t seen the first division for 14 years, since 1928. In 1943, Rick caught 70 games for a .987 fielding average with 327 put-outs.

On March 1, 1944, the St. Louis-Washington express traded Ferrell back to manager Ossie Bluege’s Washington Senators for Gene Moore and cash. There during the 1944-45 seasons (at age 38 and 39), Rick was faced with catching the Senators’ rotation of four knuckleball starters (Leonard, John Niggeling, Roger Wolff, and Southpaw Mickey Haefner), the only catcher in major-league history to accomplish such an arduous feat. The “butterfly pitch” was an unpredictable pitch that was extremely difficult to hit and catch. When asked how he did it, Ferrell would reply, “Never reach for the knuckleball; I just let it come to me.” Although Ferrell led the league in passed balls both years, he was selected with Stan Spence to represent the Senators in the 1944 All-Star Game, but did not see action. The Senators finished the season in eighth- and last- place while Ferrell’s former team, the St. Louis Browns, finished in first. Rick had just missed playing on the pennant-winning team, something that eluded him his entire catching career. In 99 games, Ferrell garnered a .277 batting average.

Tides turned in 1945 as the Senators began steadily winning. In July at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Ferrell broke Ray Schalk’s American League record for most games caught (1,721) as Schalk watched him from the crowd. Although no All-Star Game was played due to World War II, Rick was selected for the theoretical team. In the final week of the 1945 season, Ferrell, along with catcher Al Evans, helped the Senators come within one-and-a half games of winning the American League pennant, ultimately clinched by the Detroit Tigers and Hank Greenberg’s grand-slam home run in the top of the ninth of the critical final game of the season. The four Senators knuckleball pitchers had totaled 60 wins out of 87 team victories. After retiring to coach the 1946 season, Ferrell put on his catching gear again in 1947 at age 41 to return to catch 37 games for the seventh-place Senators, hitting .303.

Rick Ferrell caught his final major league game on September 14, 1947, retiring as a player after 18 seasons in possession of the American League record for most games caught: 1,806. His lifetime batting average was .281; slugging average: .363. An astute judge of pitches, Rick tallied only 277 strikeouts in 6,028 at-bats, and drew 931 career walks. Nineteen percent of his 1,692 hits were doubles (324). With only 28 career homers, Ferrell, like fellow old-time catchers Roger Bresnahan (26) and Ray Schalk (11), was clearly a contact, rather than a power, hitter. His lifetime fielding average was .984. Ferrell coached another two years (1948-49) for the Senators and returned to the Detroit Tigers organization—his original organization– to coach (1950-54) before retiring from the field altogether.

After 25 years in uniform, most baseball players leave the game to pursue other endeavors. However, baseball lifer Rick Ferrell progressed through the Tigers’ ranks for the next four decades. He advanced to being a scout (1955-’57) for the Southeastern region (North and South Carolina and parts of Virginia and Tennessee), Tigers’ scouting director in Detroit (1958), then general manager and vice president (1959 –’74), and finally, to executive consultant (1975 – ’92) of the Tigers for President Jim Campbell. Under owners John Fetzer and Domino’s Pizza magnate Tom Monaghan, Ferrell was valued as a hard-working gentleman of class and integrity with encyclopedic baseball knowledge and an acute ability to evaluate talent. His perpetually calm demeanor– seldom found in those of keen intelligence– brought balance and stability to a sometimes manic front office. “When I was telecasting for the Tigers, everybody wanted to be like Rick Ferrell- so calm, so soft-spoken, a real gentleman,” wrote Hall of Fame third baseman George Kell to the author in a note dated January 2008.

During his administrative tenure, before the age of computerization, Rick was the “central computer” for the Detroit Tigers, able to retain vast amounts of baseball data in his “Big Brain,” a nickname given him as a player. The Detroit Tigers won two World Series (1968, 1984), two AL pennants (1968, 1984), and three divisional championships (1972, 1984, 1987), while placing second six times. Players like Al Kaline, Denny McLain, Mark Fidrych, Jack Morris, Lou Whitaker, and Alan Trammell played for Detroit through the years. Rick also served as a 20-year member on the Major League Baseball Rules Committee, voting on changes to baseball like the designated hitter rule.

A family man whose wife died in 1968, Ferrell was father to four children, two daughters and two sons, whom he raised first in Greensboro, North Carolina, then in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, a well-to-do “old money” suburb of Detroit. Out at Tiger Stadium in the summertime, they attended most Tiger games, watching from Rick’s front-row, third base line box seats and literally growing up at the ballpark. On off-days, Ferrell enjoyed playing golf and exercising; he actually took up the game of tennis at age 70. Staying in shape was always a priority for this optimist, forever youthful and appearing much younger than his age, despite his baldness.

On August 12, 1984, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee inducted Rick, 78, along with shortstop Pee Wee Reese, into the National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, NY, bringing the ultimate recognition to one of baseball’s quiet, devoted heroes. “I know of no one who deserves the Hall of Fame more than Rick Ferrell,” wrote Detroit Free Press sportswriter Mike Downey in August 1984. “I don’t know how they kept him out for so long,” commented Kell to the Free Press then.

In August 1988 after more than forty years, Ferrell’s American League most-games caught record was broken by Hall of Fame White Sox catcher Carlton Fisk at Tiger Stadium, this time with Rick in the stands to congratulate his successor.

When Little Caesars Pizza owner Mike Ilitch purchased the Detroit Tigers in 1992, Ferrell, 86, finally retired from baseball altogether, with his 66-year baseball career having “excellence” written all over it. Not only were Rick’s athletic accomplishments outstanding, but also his inner character and impeccable reputation were of the highest caliber. Three years after his retirement from the Detroit Tigers, Rick Ferrell, 89, passed on in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, on July 27, 1995, three months shy of his 90th birthday.

Sources

The Baseball On-line Library

Ferrell, Kerrie with William M. Anderson. Rick Ferrell, Knuckleball Catcher, A Hall of Famer’s Life Behind the Plate and in the Front Office. (McFarland, 2010).

Thompson, Richard. The Ferrell Brothers of Baseball. (McFarland Press, 2005).

Boston Globe

Greensboro Daily News and Record

St. Louis Post Dispatch

The Sporting News

Full Name

Richard Benjamin Ferrell

Born

October 12, 1905 at Durham, NC (USA)

Died

July 27, 1995 at Bloomfield Hills, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.