Clay Touchstone

Although right-handed, side-armed pitcher Clayland Maffitt “Clay” Touchstone Jr. has a sparse major-league resume — no decisions in 12 games spread over parts of three seasons, including a 16-year gap between appearances at one point — he nonetheless had a long, often successful career in the minor leagues, winning 272 games, making multiple all-star teams, and having sufficient fame that car dealers and appliance stores used his name and photo to sell radios, refrigerators, and automobiles.

Although right-handed, side-armed pitcher Clayland Maffitt “Clay” Touchstone Jr. has a sparse major-league resume — no decisions in 12 games spread over parts of three seasons, including a 16-year gap between appearances at one point — he nonetheless had a long, often successful career in the minor leagues, winning 272 games, making multiple all-star teams, and having sufficient fame that car dealers and appliance stores used his name and photo to sell radios, refrigerators, and automobiles.

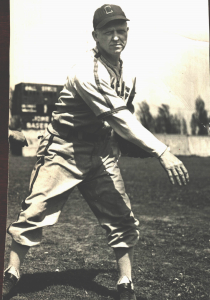

Described in newspaper accounts as blond and burly, right-handed-hitting Touchstone (listed at 5-feet-9, 170 pounds) was born on January 24, 1903, in Prospect Park, Pennsylvania, as the sixth of seven children of Clayland M. Touchstone Sr. and Ada B. (Strout) Touchstone. There is evidence that he tried throughout his career to shave two years off his age. Although the 1910 census has his date of birth as 1903, a 1945 player questionnaire lists it as 1905.1 Likewise, several 1925 articles reporting his signing his first professional contract, with Waterbury of the Eastern League, give his age that year as 20, as do several articles from early 1926 when the Cubs invited him to spring training.2 Articles announcing his signing a contract with the Chicago White Sox in 1945 also reduce his age by those two years.3

During Touchstone’s childhood, his father worked in various capacities in the railroad industry, while census records describe his mother as not being employed outside the home. Touchstone appears to have gotten only as far as the eighth grade in his education, at Prospect Park’s Lincoln Avenue School; by the time of the 1920 census, when he was 17, his occupation was listed as messenger boy for a steam railroad.4 He grew up in something of a baseball family, as his oldest brother, Vernon Touchstone, spent two seasons, 1907 and 1909, in the minor leagues. Touchstone credited Vernon with helping him develop as a pitcher.5 In 1928 several newspapers reported that a second brother, Fred Touchstone, was a member of the Providence Grays, although neither Baseball-Reference nor Retrosheet shows any statistics for him.6 Another article from that year describes Fred as briefly a bullpen catcher for the Boston Braves.7

Starting in 1922, Touchstone spent three seasons playing semipro ball in the Philadelphia area, primarily as a pitcher but also in the outfield and infield on days he wasn’t on the mound, acquiring a reputation for his “powerful right arm” and a “trusty bat.”8 With Salem in the Salem County League in 1922, he went 18-6.9 The next year, he moved to a team sponsored by Lit Brothers Department Store in the Philadelphia Baseball Association, finishing the season 21-7.10 In September that year, Lit Brothers played an exhibition against a rival, Ascension Catholic Church, which featured Babe Ruth at first base, participating as a favor for the church’s pastor, Father William Casey, to help raise money to pay off the parish debt for its athletic field.11 (Lit Brothers won 2-1, as its pitcher, Howard Gransbach, held Ruth to one hit in three at-bats.12) The next season, Touchstone was once again back with Lit Brothers, then in the Penn-Jersey League, reportedly going 15-8.13

In August of 1925, after he threw a one-hitter in a game against Ascension that ended in a 0-0 tie, the Detroit Tigers invited Touchstone to a tryout, although it appears they did not offer him a contract, since going into the 1925 season Touchstone was preparing to play for another Penn-Jersey League semipro team, Camden.14 However, instead he got an offer from Waterbury of the Eastern League when Billy Whitman, manager of the Penn-Jersey team in Chester, who also doubled as a scout for the Chicago Cubs, recommended him to Waterbury manager Kitty Bransfield.15

Touchstone made his professional debut on April 24, 1925, in relief in a 5-4 loss to the Springfield Ponies in Springfield; the box score shows he pitched in the eighth inning, likely facing a single batter, as his line was zero innings, no hits, no strikeouts, one walk.16 He got his first professional start the next day, also in Springfield, going nine innings in a game that ended a 2-2 tie when the umpires stopped it on account of darkness. Touchstone allowed five hits, walked three and struck out seven, while collecting his first professional hit, a double.

Throughout the season, in which Waterbury won the championship, Touchstone alternated between starting and relieving; once in a while, his name shows up in a box score playing the outfield or as a pinch-hitter. In all, he appeared in 65 games, 46 as a hurler, ranking second among Waterbury pitchers for appearances, after Jim Bishop’s 51. Touchstone’s final record was 10-11, with a 3.73 ERA, 89 strikeouts, and 95 walks.

Touchstone crowned his season in an odd fashion. On September 17 the Hartford Senators came to Waterbury for a doubleheader, with Waterbury leading Hartford by two-tenths of a percent atop the standings with four days remaining. Waterbury took the opener, 6-5 in 12 innings. Then, as the second game began, controversy arose when umpires ran out of the official league-sanctioned baseball. According to the Berkshire Eagle account, umpires procured a supply manufactured by a different company and league President Dan O’Neill, who was in attendance, gave his approval to use them. Hartford manager Paddy O’Connor immediately announced he was playing under protest. After Waterbury took a 3-0 lead in the third, the Senators scored in each of the next four, taking an 8-3 lead in the top of the seventh when they plated four off reliever Moose Fuller, prompting Bransfield to bring on Touchstone with two outs. He retired the only man he faced, ending the inning. Waterbury answered by scoring five in the bottom of the inning, the last two coming in on a long drive to right by catcher Tommy McCarthy, who tried to stretch the hit into a triple, but was apparently cut down, as the umpire ruled him out, but then reversed himself, saying the Hartford third baseman had dropped the ball. The ensuing argument emptied both benches as the “diamond took on the aspect of a riot scene.” After calm returned, the umpires ordered play to resume, but O’Connor kept his team off the field, and the umpires awarded the game to Waterbury in a forfeit. As Touchstone was the pitcher of record, he got credit for the victory.17 Waterbury never relinquished its lead in the standings and, after league owners voted to reject O’Connor’s protest, Waterbury nailed down its second consecutive Eastern League championship, the first team to win back-to-back pennants in the league’s short history to then.18

The Chicago Cubs invited Touchstone to spring training in 1926, and he was among the earliest players to report to camp.19 His progress was slowed in the second week, when he took a line drive off a shin and the injury become infected.20 However, he did have his bright moments; for example, he earned a positive notice in the Chicago Tribune for his performance in a March 9 intrasquad game when he threw four scoreless innings after the opposing squad had pummeled starter Tony Kaufman for 11 runs in the first five frames.21 Despite that, the team assigned him to Waterbury once again, as the final player cut before Opening Day.22 However, Touchstone refused to report, and instead went home and spent the season playing in the Camden County semipro league, under an assumed name, Johnny Carr.23

Before the 1927 season, Waterbury sold Touchstone to another Eastern League team, the Providence Grays, and he turned in solid work there over the next two years. In 1927 he went 17-17 with a 3.73 ERA, 99 strikeouts, and a league-high 128 walks for a team that finished last, at 61-91. In 1928 he made his first minor-league all-star team when he went 16-13 with a 3.27 ERA and finished third in the league in WHIP among pitchers with at least 150 innings, 1.264. He also recorded 100 strikeouts against 77 walks.

That September, the Boston Braves recalled Touchstone and he made his major-league debut in the second game of a doubleheader against Brooklyn on September 4, coming on in the top of the eighth with Boston trailing 5-2 and playing as if they were “in a trance on the field.”24 Babe Herman greeted him with a bunt single down the third-base line, and the second batter reached as well when Braves first baseman George Sisler made a wild throw after fielding a groundball, putting runners on second and third. Touchstone induced the next batter to ground to short, the runners holding, but then Rube Bressler’s single plated both runners. With two outs, Touchstone walked a man and gave up a two-run triple to Watty Clark, before closing out the ugly inning on a lineout to center. He managed to get through the ninth with no further damage — allowing only a single — giving him a final line of two innings, four runs, all unearned, four hits, one walk, no strikeouts.

In all, Touchstone saw action in five games that month, as the Braves finished out a miserable season, ending up 50-103, in seventh place. Touchstone recorded no decisions in throwing eight innings, finishing with a 4.50 ERA, allowing eight runs, four earned, on 15 hits and two walks, while registering one strikeout, which came in his final appearance that year, on September 25, when he fanned the Pirates’ Mack Hillis. That last game saw Touchstone’s longest outing of the season with Boston: He went four innings, garnering his first strong notices from the Boston press. He came on to begin the top of the fourth with the Braves down 8-1 and steadied the ship enough to allow Boston to creep back into the game, allowing single runs in the fifth and sixth, while Boston was scoring seven. While Boston ended up on the short side of the eventual 13-8 score, Touchstone earned praise from two Boston daily newspapers. The Globe said, “Touchstone was the only Boston pitcher who could hold the visitors.”25 The Herald was even more enthusiastic, saying he was “easily the best of the four Boston pitchers,” and adding that after he entered the game, “Boston looked better, because the Pirates could not take liberties with his stuff.”26

Boston returned Touchstone to Providence for 1929 and he had his best year in professional ball to that point, going 22-12, leading the league in innings (292) and strikeouts (132), and finishing second in victories. His ERA of 3.39 ranked second among hurlers with at least 150 innings, as did his WHIP of 1.301. He also gained his second consecutive selection to the Eastern League all-star team. His success earned him a second trip to the major leagues, when Boston called him up in September. This time Touchstone saw action in only a single game, 2⅔ innings in relief against the Pirates on September 20. He came on with one out and a runner on second in the bottom of the sixth and suffered what would turn out to be the worst stint in his brief major-league tenure, allowing five consecutive hits, three for extra bases, capped by a three-run home run by Lloyd Waner, increasing the Braves’ 4-2 deficit to 10-2. He managed to go the rest of the distance without allowing another run, giving up only one more single. His line for the game (and that major-league season): 2⅔ innings, five runs (all earned), six hits, no walks, one strikeout (of Bill Windle, in his second and final major-league plate appearance).

Although his game on the mound was abysmal, Touchstone did have one career highlight that day, his first and, as it turned out, only major-league hit, a one-out single to left in the eighth inning, off Jesse Petty. While Touchstone advanced to second with two outs, on a single by Freddie Maguire, that was as far as he got on the basepaths, as the next hitter, Sisler, grounded out, ending the inning.

In nearly every other era of baseball history, that likely would have been the end of Touchstone’s major-league career, such as it was. However, he did have one more shot at the big leagues — only he had to wait 16 years.

Boston assigned Touchstone to Newark of the International League for 1930. In May, with his record 1-2, Boston sold his contract to the Southern Association Birmingham Barons.27 There, he became a bona fide star. Even before he arrived, the local press was lauding him. Describing him as a “burly right-hander” and, because of his 1929 workload, “a real life iron man,” the Birmingham News said, “Touchstone is a hurler of proven Class A ability (who) should cop a lot of games in the Southern, provided the climate agrees with him. … (He is) a curve ball pitcher, although he has a fast one, a knuckler and one or two other varieties in his repertoire.”28 He made a positive impression nearly immediately, starting his first game as a Baron in Atlanta on May 26 and going the distance in an 11-inning, 3-2 victory, again earning effusive praise: “In addition to showing (Atlanta) a world of stuff, Clay Touchstone showed that he had courage … to keep right on pitching in the face of adversity and blasted chances for runs. Few Baronial hurlers have broken in with the goods the former Boston Brave put on display for 11 innings. … Touchstone’s hurling should serve as a great tonic for the Barons.”29

Touchstone went 15-6 with the Barons, giving him a combined record for the year of 16-8. His 15 victories with the Barons ranked second on the team, despite his joining it in late May and also missing the final week when he returned to Pennsylvania because his mother had fallen ill, dying on September 9.30 His performance earned him his third selection to a minor-league all-star team, and helped establish him as enough of a name in the city that a local car dealer ran a photo of him and two of his teammates buying Buicks to promote the dealership, and a local appliance store hired him to sell radios and refrigerators during the offseason, using Touchstone’s photograph and name, and those of several other professional ballplayers, in its advertising.31

Although 1931 turned out to be a bit of a down year for Touchstone — he posted his worst minor-league ERA to that point, 4.76, highest among all Barons hurlers that year, although he did win 15 games (against 11 losses). He did have one significant positive moment. After the Barons won the Southern Association in a bit of a walk, finishing 10½ games ahead of second-place Little Rock, they met Texas League champ Houston in the annual best-of-seven Dixie Series. Houston was led that year by two future Hall of Famers: Dizzy Dean, who’d been spectacular, leading the Texas League in wins (26) and strikeouts (303), while posting a 1.53 ERA, and Joe Medwick, who’d led the league in home runs (19) and RBIs (126). The first four games were pitchers’ duels, all shutouts, as Birmingham took the opener, defeating Dean 1-0, and Houston took the next three by scores of 3-0, 1-0, 2-0, pushing the Barons to the brink of losing the series. To start the win-or-go-home game five, Barons manager Clyde Milan tapped Touchstone, his first action in the series, and he responded by “going the route in never-wavering fashion, speeding down the last five innings like a midnight express passing through a tank town,” scattering seven hits in nailing down a 3-1 victory that kept Birmingham alive.32 The Barons won the last two, bringing home the championship, their second in three years.

Touchstone spent two more seasons in Birmingham. He struggled again in 1932, posting a league-high ERA among pitchers with at least 150 innings, 5.56, although he did manage to go 16-15, for a fifth-place Barons team that finished 68-83. The next season, however, was far better. Touchstone began working out in earnest in January, prompting Milan to predict he would win 20 games.33 He got the ball as Opening Day starter; while he allowed 10 hits, he “flashed an amazing curve” and went the distance in the victory.34 He went on to win six in a row in all, finally losing his first of the season on May 11. By the end of the June, he was 12-5 and pitching so well that the Barons staged a “Touchstone Day” at the ballpark during a July 2 doubleheader, at which Touchstone hosted semipro pitchers in a skills competition in between the two games, and fans presented him with a Gladstone bag. Then he had his worst day of the season to that point, losing 8-7 when he allowed two runs with two outs in the top of the ninth.35 He finished the season 21-13 (his 21 wins tied for tops in the Association), and ranked third both in innings pitched (283) and ERA among hurlers with at least 150 innings (3.21). His performance landed him his fourth all-star selection, in both the Associated Press and United Press polls.36

Despite his success on the field, and the postseason recognition, Touchstone ended 1933 on an unfortunate note: On December 30, he and shortstop Jess Cortazzo were arrested for possession of alcoholic beverages and operating a game of chance; Touchstone pled guilty in early January 1934, paying a fine of $40, and his plea led the court to drop the charges against Cortazzo.37 Roughly three weeks later, the Barons traded Touchstone to Memphis for a career minor-league southpaw, Clarence Griffin. Some reports suggested the arrest might have been a factor in the deal: “In Touchstone’s case there must have been some motive other than a desire for southpaw strength, as the portly curve-baller found his best stride … last year. … Perhaps the idea of ‘cleaning house’ balanced the ledger. … Again the difficulties Clay found himself in when officers discovered beer at his lunch stand bore some influence.”38

Touchstone spent three seasons in Memphis, with uneven success. The team acquired him hoping to build on the prior two seasons when they had finished with the best overall record in the Southern Association. It was not to be, as Memphis never repeated during Touchstone’s tenure there. In 1934 he experienced his first sub-.500 season since his initial year in professional baseball, finishing 16-18, although his 2.78 ERA ranked second among league hurlers with at least 150 innings, and his 275 innings also ranked second.

The next season Touchstone again was in the 20-win club, going 22-11 (his victories ranked fourth in the league), and he also ranked fourth in innings, 283, although his numbers may have been better than that if he had not suffered bad cuts to his hands when a water faucet snapped off when he was bathing.39 It later turned out that the injury may have cost him another shot at the major leagues, as shortly before Touchstone sliced his hands, Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, had considered picking him up but was dissuaded when it was not clear how the injury would affect his pitching.40 Nonetheless, his season landed him yet again on the all-star team, his fifth such selection.

Touchstone’s final year with Memphis was an abysmal one, for both Memphis and him. He began it by holding out in a salary dispute, not signing until mid-March.41 He didn’t make his first start of the season until April 20, the Chicks’ ninth game of the season, against New Orleans, and although he allowed only six hits and a walk in eight innings he ended up losing because he hit five batters, three of whom scored.42 He finished with his worst record to that point in his professional career, 12-18, the first time since his initial professional season that he did not reach at least 15 victories. His ERA, 4.57, was the third worst among pitchers with at least 150 innings. As far as the Chicks fortunes went, they finished last, 60-90, the first time since 1920 that they ended the season below .500 and in the second division.

After the close of the season, Memphis traded Touchstone to Oklahoma City for career minor-league pitcher Ed Marleau, and Touchstone spent two years there, performing well in each season, though not without significant challenges in the latter year.

In the first of those, 1937, he went 19-11 with a 2.53 ERA and a career-high 181 strikeouts in 277 innings, earning selection to yet another all-star team. Interestingly, he was only the second-best hurler for Oklahoma City, which went 101-58: even better was career minor leaguer Harold “Ash” Hillin, who went 31-10, with a 2.34 ERA in 302 innings; Hillin took league MVP honors.

In the offseason, Touchstone began feeling ill and when he consulted a doctor, he was diagnosed with diabetes and anemia, conditions that caused him to lose a considerable amount of weight and weakened him to the point that doctors suggested that if he were to pitch at all in 1938, it might not be until June 1.43 He did come back sooner, beginning his season in mid-April by working strictly in relief. A sportswriter from the Daily Oklahoman described one such appearance (in the nightcap of an April 24 doubleheader against Fort Worth):

“The Tribal invalid, skinny Clay Touchstone, staggered into the picture (with one out) in the second inning. … Everyone felt sorry for poor Clay, but he made his way to the pitching mound without assistance. He couldn’t stand up out there. But he got two men out. … Then, in the Indian half, his fragile wasted form presented a sorry picture at the plate. The bases were loaded. Two were out. The ghost swung and the result was a clean single into left for two tying runs.”44

Despite his slow start, Touchstone nonetheless pitched well for most of the season, ending up 16-11 with a 2.42 ERA; his victory total tied for 10th in the league, while his ERA stood eighth among pitchers with at least 150 innings, and his WHIP (0.996) was second. For his work, he earned another selection to a Texas League all-star team. Nonetheless, when the season ended, declaring they were pitching-rich and hitting-poor, Oklahoma City traded him to Dallas, for career minor-league outfielder Tony Governor, and cash.45

Perhaps mindful of his slow start in 1938, Touchstone returned his signed contract to Dallas quickly after receiving it, enclosing a note saying the was confident he was fully healthy and “rearing to go.”46 However, he suffered a leg injury in a preseason game that delayed his first regular-season appearance until the eighth game, on April 22, but his performance that day made plain that he was, indeed, “rearing” to go, as he shut out Tulsa 8-0, allowing six hits and two walks, fanning eight.47 In all that year, he threw seven shutouts, posting a record of 20-12, with a 2.70 ERA in 253 innings, and earning yet another spot on the Texas League North all-star team.48

As it turned out, that was the last truly outstanding season of Touchstone’s career, as he never again finished a year with a winning record: In 1940, still with Dallas, he went 11-14, with a 3.67 ERA in 218 innings, although he was still enough of a fan favorite that he earned a berth on the North all-star team.

Before the 1941 season, Dallas sent Touchstone back to Oklahoma City, in exchange for right-handed pitcher Otho Nitcholas. There, he ended up 13-18, with a 2.99 ERA, highest among Oklahoma City pitchers with at least 150 innings. However, in October, Touchstone was invited to participate in an exhibition game in Oklahoma City, pitting a team of “All Stars” headed by Bob Feller against the Kansas City Monarchs, whose major draw was hurler Satchel Paige.49 Paige was a no-show, as he was unable to get timely transportation from Kansas City; despite that, the Monarchs prevailed 3-2, scoring one run off Feller in his three innings of work and the other two off Ed Marleau, who took the loss. Touchstone pitched the final two frames, setting down all six he faced.50 Standing in for Paige was Booker T. McDaniels, later the first African-American pitcher in the PCL when he joined the Los Angeles Angels in 1949.51

The next year, 1942, was Touchstone’s last in the minor leagues. He was again back with Oklahoma City, which had an even worse season than the team had in 1941, finishing 58-95. In fact, the team was so awful it went through four managers, beginning with Homer Peel, who was fired on June 12 with the team 24-35, followed by scout Jimmy Payton, who served as acting manager until June 17, when the team turned to second baseman John Kroner, who resigned on August 3 after the team went 18-32 during his brief tenure. To replace Kroner, the team turned to Touchstone, who took over with the team in a challenging spot: not only was it in seventh place, but in good part because of the World War II draft, it had an active roster of only 13.52 Under Touchstone, the team ran out the string, going 14-24. As for his individual numbers, Touchstone ended up 10-17 with a 3.11 ERA.

When the season ended, the Texas League suspended operations for the duration of the war, and Oklahoma City sold Touchstone’s contract to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League.53 However, in March 1943, the 40-year-old pitcher announced that he had no interest in playing, retiring instead to run a tavern he owned in Beaumont, Texas, Service Amusement Club.54 His career minor-league totals: 272 wins, 230 losses, 1,766 strikeouts, 1,196 walks, and a 3.51 ERA.

As it turned out, Touchstone was not entirely finished with baseball. In 1945, with major-league rosters depleted by the demands of the war, the Chicago White Sox approached him about joining the team as a relief pitcher, and Touchstone agreed, telling The Sporting News that although he not thrown a pitch in more than two years, he “suddenly got the hankering to try it again and figured with manpower conditions being what they are, now would be a good time for a whirl in the majors.”55

The 42-year-old Touchstone did not see much action. Although on the roster the entire season, he pitched in only 10 innings over six games, all in relief. He recorded no decisions, put up an ERA of 5.40 on 14 hits and six walks, while striking out four. His final appearance came on September 8 against the Athletics in Philadelphia, when he came on to begin the bottom of the fifth, relieving Eddie Lopat with the White Sox losing 5-0. In an echo of his first major-league game, he was hurt by a key error, when third baseman Ray Schalk made a wild throw after fielding a groundball, eventually leading to three unearned runs. Touchstone allowed another in the seventh, on a home run by Hal Peck, which closed out the scoring in the 9-0 A’s victory. In the game, Touchstone recorded his sixth and final major-league strikeout, of pitcher Jesse Flores leading off the bottom of the seventh. The final major-league batter Touchstone faced was George Kell, who grounded back to Touchstone for a 1-3 putout.

When the season ended, with the regulars returning with the end of the war, the White Sox released Touchstone, assigning him to Little Rock, but he elected not to report, giving up the professional game once and for all. He returned to Beaumont to run his amusement club, until his death on April 28, 1949, of pulmonary thrombosis.56 He left a wife, Elsie (Crowel) Touchstone, whom he’d married in 1928, as well as three sons. Touchstone is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Beaumont, Texas.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author referred to The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, editors; The Minor League Register, Lloyd Johnson, editor; Minor League All Star Teams 1922-1962, by James Selko; as well as Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org. He also consulted SABR’s BioProject.

Notes

1 1910 Census; The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for Oklahoma, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 511;

2 “Eastern League Notes,” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), March 9, 1925: 13; “Prospect Park Hurler Signs,” Delaware County Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), March 5, 1925: 11; “Cubs Line Up 14 Pitchers for Trip,” San Antonio Light, January 31, 1926: 37.

3 “Game in Touchstone’s Blood,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1945: 16.

4 “Prospect Park Hurler Signs,” Delaware County Daily Times, March 5, 1925: 11; “Eastern League Notes,” Berkshire Eagle, March 9, 1925: 13.

5 “Prospect Park Hurler Signs.”

6 “Have a Brother Battery,” News Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania), August 3, 1928: 13.

7 “Eastern League Notes,” Berkshire Eagle, August 13, 1928: 13.

8 “Lit Brothers Defeat Camden in Fast Game,” Morning Post (Camden, New Jersey), August 15, 1928: 4.

9 “Prospect Park Hurler Signs.”

10 “Prospect Park Hurler Signs.”

11 “Ruth in Sandlot Game,” Washington Evening Star, September 5, 1923: 24.

12 “Pitching Battle Draws Interest,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) New Era, September 6, 1923: 12. Gransbach later spent five years in the New York-Penn League, pitching for four different teams. The writer was not able to determine whether Touchstone appeared in the game; there do not appear to be any extant box scores.

13 “Eastern League Notes,” Berkshire Eagle, March 9, 1925, 13.

14 “Lits and Ascension in Scoreless Deadlock,” Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey), August 1, 1924: 19; Unheadlined note about Touchstone, Courier-Post, August 4, 1924L 19; “Swigler Will Not Play for Camden,” Courier-Post, February 21, 1925: 12.

15 “Prospect Park Hurler Signs.”

16 “Ponies Win in Initial Game on Home Field, 5-4,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Telegram, April 25, 1925: 24.

17 “Ponies Win in Initial Game on Home Field, 5-4.”

18 “Only One Game in Brass City Today,” Hartford Courant, September 20, 1925: 37.

19 John Hoffman, “Several Rookies Join Bruins for Drive to Pennant,” Chicago Daily News, February 10, 1926: Two-1.

20 “Caught on the First Hop,” Camden Courier-Post, March 4, 1926: 24.

21 Irving Vaughan, “Cub Subs Drub Cubs Regulars,” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1926: 23.

22 William H. Becker, “Cubs Are Ready,” Chicago Daily News, April 12, 1926: Two-1; “Touchstone Released, Will Join Waterbury,” Camden Courier-Post, September 29, 1926: 20.

23 “Demoe, Touchstone sold to Providence Nine,” Boston Globe, December 1, 1926: 13; “Circuit Also Approves Deighan and Spaulding” Camden Courier-Post, September 3, 1926: 30.

24 James C. O’Leary, “Three Home Runs in Braves Double Loss,” Boston Globe, September 5, 1928: 12.

25 James C. O’Leary, “Pirates Get Very Busy and Beat Braves, 13-8,” Boston Globe, September 26, 1928: 13.

26 Burt Whitman, “Pirates Swamp Braves, 13-8,” Boston Herald, September 26, 1928: 22.

27 “Providence Fails to Land Pitchers from Newark Club,” Scranton Republican, May 16, 1930: 16.

28 James L. Conners, “Barons Obtain Iron Man in Touchstone,” Birmingham News, May 20, 1930: 18.

29 Zipp Newman, “Dusting ’Em Off,” Birmingham News, May 27, 1930: 17.

30 “Former Baron Blanks Milans with One Hit,” Birmingham News, September 9, 1930: 16.

31 “Three Members of Baron Team Buy Buick Automobiles from Drennen Motor Car Co.,” Birmingham News, September 14, 1930: 40; display ad for West End Radio Co., Birmingham News, October 5, 1930: 17.

32 Zipp Newman, “Clay Touchstone Gives Barons Second Victory, 3-1,” Birmingham News, September 22, 1931: 10.

33 Zipp Newman, “Dusting ’Em Off,” Birmingham News, January 20, 1933: 9; Zipp Newman, “Dusting ’Em Off,” Birmingham News, March 10, 1933: 16.

34 Zipp Newman, “Manager Milan Chased by Ump in First Inning,” Birmingham News, April 12, 1933: 8.

35 Zipp Newman, “Bill Hughes Blanks Vols in Nightcap,” Birmingham News, July 3, 1933: 5. According to the Birmingham News account, a pitcher named Lewis Reynolds won the skills competition.

36 “New Orleans Pels Land Three Stars on All-Loop Team,” Birmingham News, September 11, 1933: 8; “Managers Pick Lee Head,” Knoxville Journal, September 12, 1933: 7.

37 “Barons Arrested,” Birmingham News, December 31, 1933: 1; “Touchstone Fined,” Birmingham News, January 4, 1934: 4.

38 Bob Murphy, “Tommy Keeps Modesty; ‘Revenge’ Game Starts Tough for Mr. Mack,” Knoxville News Sentinel, February 16, 1934: 12.

39 “Touchstone Injured,” Knoxville Journal, September 8, 1935: 16.

40 Don Whitehead, “Clay Touchstone Hopes to Shake Off Injury Jinx This Year,” New Orleans State, May 13, 1936: 8.

41 “Memphis Pitcher Is Not Satisfied with Terms,” Tampa Tribune, February 14, 1936: 19; “Rain Halts Chick’s Drill, Clay Touchstone Signed,” Tennessean (Nashville), March 17, 1936: 17.

42 “Memphis Star Plunks Five Pels in Ribs,” Tennessean, April 21, 1936: 9.

43 Jim Hopkins, “Touch Says He’ll Be Ready,” Oklahoma News (Oklahoma City), March 29, 1938: 10.

44 Charles Saulsberry, “Hillin Gains Shutout, 6-0, Draws Second Victory, 6-5,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), April 25, 1938: 8.

45 Charles Saulsberry, “Governor Is Obtained in Indian Swap,” Daily Oklahoman, November 15, 1938: 16.

46 “Touchstone Signs Dallas Contract,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, January 20, 1939: 20.

47 “Tulsa Drops Game to Indians, Dallas Gets New Nickname,” Monitor (McAllen, Texas), April 10, 1939: 5; “Rebels Drub Tulsans, 8-0,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 23, 1939: 12.

48 Tony Governor, the player that Oklahoma City got in exchange for Touchstone in their search for a bat, ended up not providing much help: he appeared in only five games with them, going 3-for-19, and then temporarily retired from professional baseball, only returning five years later, when the minor leagues were in search of bodies to fill rosters that had been depleted by the military draft.

49 John Cronley, “Satchel Paige Opposes Bob,” Daily Oklahoman, October 5, 1941: 39.

50 John Cronley, “Monarchs Are the Best After Feller Leaves,” Daily Oklahoman, October 9, 1941:18.

51 Prescott Sullivan, “The Low Down,” San Francisco Examiner, June 15, 1949: 27.

52 “Touchstone Takes Over as Okla. City Manager,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1942: 1.

53 C.M. Gibbs, “Gibberish,” Baltimore Sun, February 25, 1043: 18.

54 “Jones Signs Pact, Touchstone Quits,” Baltimore Sun, March 20, 1943: 8.

55 “Game in Touchstone’s Blood.”

56 Clay Touchstone death certificate, on file in the National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives.

Full Name

Clayland Maffitt Touchstone

Born

January 24, 1903 at Moore Township, PA (USA)

Died

April 28, 1949 at Beaumont, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.