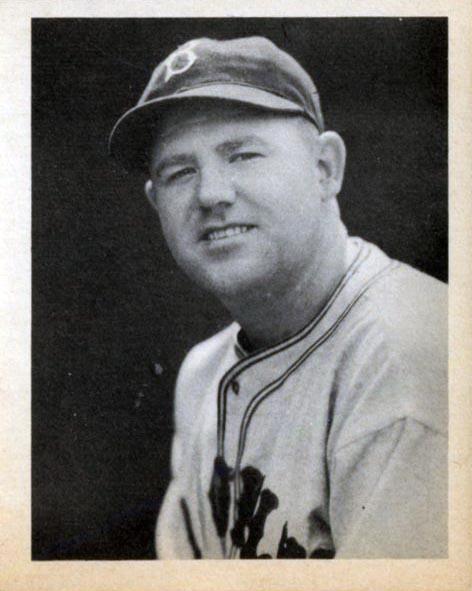

Babe Phelps

New York’s Penn Station was all hustle and bustle on the sunny afternoon of June 12, 1941. The Brooklyn Dodgers were gathering to board a train bound for Pittsburgh. The trip would then continue west to St. Louis, where a crucial series with the Cardinals awaited the two early rivals in the National League pennant race.

New York’s Penn Station was all hustle and bustle on the sunny afternoon of June 12, 1941. The Brooklyn Dodgers were gathering to board a train bound for Pittsburgh. The trip would then continue west to St. Louis, where a crucial series with the Cardinals awaited the two early rivals in the National League pennant race.

Dodger manager Leo Durocher was anxiously pacing through the waiting area. He quietly made a mental headcount of his assembling players. He checked again and notably absent was his veteran catcher Babe Phelps. He dispatched coaches to make some calls – attempting to locate the missing player. In vain, he even delayed the train, hoping against hope that the backstop would arrive shortly. Finally, the train left the station, as a dismayed Durocher tried to figure out what to tell his boss, General Manager Larry MacPhail.

Across town, after seeking out a doctor, the missing Babe Phelps headed back to his hotel. He packed his bags and prepared to head, with his wife, back to their home in Maryland. He didn’t know it at the time, but for all intents and purposes, his seven-year stint with the Dodgers was over. The last player from the era known as the “daffiness boys” was about to pass into history.

What led Ernest Gordon “Babe” Phelps to this crossroad in his career?

The future all-star was born on April 19, 1908, in what was then a very rural Odenton, Maryland. One of ten children, Phelps and his siblings would play baseball in the abundant space of open fields that dominated the Maryland countryside. Showing lots of talent for the game, the lefty-swinging youngster played for a variety of local teams. He caught the eye of the manager of a team in Bowie, Maryland: a key series was approaching with rival Mt. Rainer and high caliber players were needed for the match-up. Young Gordon had a banner day, going 6 for 7 at the plate, providing the offense needed for victory.

Phelps’ exploits caught the attention of Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators. Griffith eventually offered the young ballplayer his first professional contract and assigned him to Hagerstown in the Blue Ridge league for the 1930 season, where he compiled a batting average of .376. Moving through the minor league system, with stops at Youngstown and Albany over the next two seasons, provided more seasoning for the solid hitting young prospect. In 1931, he was called up to the big club at the end of the season for the proverbial “cup of coffee.”

Phelps always had fond memories of those early days when manager Walter Johnson would hit him fungoes by the hour trying to improve his skills with the glove. His time on the diamond was usually spent in the outfield or at first base. He moved behind the plate during an emergency situation in the minors, volunteering to catch when no one else was available to fill the position.

Phelps related the kindness of Washington veteran Goose Goslin, who allowed him to use his bat when given a turn in the cage by manager Johnson. The bat felt good and “Babe” took to it as easily as he took to his new nickname. Babe always preferred a relatively small bat-especially for a big man-generally swinging a 31″ model weighing 28 ounces.

The moniker “Babe” came as a result of his resemblance to a legendary slugger. The 6’2″, 235-pound Phelps was built like the immortal Babe Ruth. His stance and swing bore a similar appearance to that of the Yankee Bambino. Later in his career, as his physique matured, Phelps would also be referred to as “Blimp.”

Dealt to Chicago, he donned the Cubs uniform for 1933 and 1934, hitting .286 in each of those campaigns despite limited plate appearances. The Cubs were contenders in ’33 and ’34, boasting a strong lineup that included future Hall of Famer Gabby Hartnett behind the plate. Based on that level of competition, the young Phelps was considered an expendable commodity. As a result, he was sold to Brooklyn in 1935 for what was essentially the waiver price. Legendary manager Casey Stengel quickly put him to work.

Stengel was starting his second season as the field manager of the hapless Dodgers. This was the era of humorous quips by vocal fans that loved to rile their beloved “Bums,” as evidenced by the classic line, “How are the Bums doing?” The response was “great – they’ve got 3 men on base!” To which the quizzical fan would then reply – “Oh yeah, which base?” – mimicking a scenario that actually did occur!

Babe Phelps fit right in. He got along well with Stengel and quickly assumed the role of back-up catcher, behind Al Lopez. He proceeded to hit a mighty .364 in 121 at bats, impressing Stengel with his offensive ability and prowess as a pinch hitter. Although not a stellar performer defensively, his hitting abilities were becoming quite evident and provided much needed punch in the Dodger lineup.

1936 saw Lopez dealt to the Braves, with Phelps now sharing the catching duties with Ray Berres. The position essentially was “platooned” by Stengel who later, as manager of the Yankees, would turn the platoon system into a (not so exact) science. Phelps responded by blossoming during the ’36 season, hitting a hefty .367 – battling veteran Paul Waner for the batting title right down to the last day of the season. Although ultimately finishing second to Waner for the crown, his .367 mark is still the record for a catcher qualifying for the batting crown.

Under the tutelage of Stengel, for whom Phelps had the utmost respect, a little of the “daffiness” syndrome began to surface. The Dodger teams of this era had a reputation for being “colorful,” and Phelps was not to be excluded: The Dodgers lost a close one in the ninth inning when catcher Phelps called for knuckleballer Dutch Leonard to throw a fastball. The resulting pitch was quickly knocked out of the park to end the game. In the dugout, Stengel asked Phelps why he had called for a fastball. Phelps responded, “His knuckle ball is tough to catch!” The exasperated Stengel responded, “If his knuckler’s tough to catch, don’t you think it might be tough to hit too?” Stengel’s advice was too late to save his own job; 1936 would be his last season as the Dodger skipper.

In 1937, Phelps posted a batting average of .313, while leading the team in doubles (37), extra base hits (47), and slugging percentage (.469). He saw action in 121 games (111 behind the plate) and would make 442 plate appearances during this productive season. On September 3 against the Giants, Phelps finished five-for-six, with a double and triple.

Unfortunately, as the season drew to a close, the Dodgers would still be mired in the second division, finishing sixth with a 62-91 record under new manager Burleigh Grimes.

January 19, 1938, was a significant date in Dodger history. On that momentous day, Larry MacPhail signed a contract giving him complete control of the operation of the ball club. The team was in dire straits. Still feeling the effects of the Depression, the club was losing money and ownership could scarcely afford the hemorrhaging of cash. Ebbets Field had fallen into disrepair, the team was a perennial loser and no evidence of change was on the horizon. This desperate situation led the Board of Directors to coax MacPhail out of his family business and back into baseball.

The roaring redhead had been out of the game since resigning from the Cincinnati Reds after the 1936 season. A falling-out with new owner Powel Crosley perpetuated that move. As general manager of the Reds, MacPhail had been a positive influence, initiating night baseball and essentially building the team into what would become the pennant winners of 1939 and 1940. He entered the scene in Brooklyn with his usual vigor, immediately secured financing to spruce up the ballpark and increase its capacity, while also reviving the lineup with some fresh players.

Babe Phelps’ tenure as backstop continued in 1938. Although injuries limited his playing time to only 66 games with 208 at bats, Blimp contributed a .308 batting average while being named to the National League All-Star team, an honor that would be repeated in 1939 and 1940. The 1939 contest was held on July 11 at Yankee Stadium and was the first All-Star Game ever televised. The American League won 3-1, with Blimp going 0-for-1 on a ground out in the seventh inning. (“Blimp” was by now an unofficial moniker attached to the big catcher; he had passed his 30th birthday and it more aptly described his physique).

Nineteen thirty-eight saw the advent of another MacPhail innovation at Ebbets Field: the addition of a lighting system for night baseball. The historic event occurred on June 15, with 38,748 in attendance. Phelps caught the game and later recalled the impressive fireworks display preceding it. This left a “mist” in the air that he claimed affected visibility. The Reds, who apparently saw well enough to score six runs, won the contest. This game, incidentally, was won by Cincinnati southpaw Johnny Vander Meer, pitching his second consecutive no-hit game. Phelps recalled the southpaw as being wild that night and occasionally the Dodgers were able to hit the young pitcher pretty hard, but the drives were right at Reds players. Vander Meer walked three in the ninth inning (including Phelps on four pitches), but the no-hitter stayed intact and went into the record books.

During the season, the Dodgers signed a man who was arguably the greatest attraction in the game: the legendary Babe Ruth! Although he was now way past his prime, it was thought that Ruth could still attract crowds. Hiring Ruth as a coach, management wanted the home run king to entertain fans during batting practice. Ruth saw it as a possible path to a managerial post, especially since MacPhail was increasingly disappointed with Grimes’ leadership.

Ruth and Phelps became fast (if not unlikely) friends. The two were Maryland natives and enjoyed each other’s company. They had an unofficial contest during batting practice, placing a friendly bet on who would hit the most pitches out of the ballpark. The prize of a cigar went to the winner. Since he was hired to put on a show during batting practice, it can be assumed that Babe Ruth won lots of cigars from Babe Phelps. Although completely different personalities, they would often sit together in the hotel lobby, after a game and before dinner. Phelps would marvel at passers-by who would glance and remark to companions “That’s Babe Ruth,” while Phelps sat and quietly took it all in.

Phelps often was allowed to travel with his wife Mabel and daughter Janet. Upon the acquisition of Ruth, a sportswriter asked young Janet her opinion of the addition of the “Sultan of Swat” to the Dodgers. She reportedly responded, “Oh, he won’t be any help!” On another occasion, the huge Ruth placed young Janet on his lap and asked, “Who’s the greatest ballplayer?” The youngster responded, “My daddy!” The Phelps family always remembered the great Babe Ruth as a lovely man and friendly person.

For the 1938 season, the Dodgers also acquired veteran shortstop Leo Durocher from the Cardinals. During the season, it became obvious that he was also lobbying MacPhail for the job of field manager. A change was in order. Manager Grimes surmised that he would not be back, and the fiery Durocher ultimately prevailed. The Bums finished a disappointing seventh in 1938, marking the end of Grimes’ second (and last) season as field boss. Durocher would make his managerial debut in 1939.

Things were changing in Brooklyn, and the tandem of MacPhail and Durocher would not tolerate a losing team. Phelps once again was penciled in as the regular catcher in 1939. However, he saw action in only 98 games while posting a batting average of .285. The relationship between Phelps and Durocher is interesting to note. Apparently, they did not care for one another prior to becoming teammates. After Durocher joined the Dodgers, the relationship changed, possibly due to the fact that Phelps admittedly did not get along with Grimes and Leo was looking for allies. A pre-game ritual developed, with Durocher and Phelps donning their gloves and warming up together on the sidelines. Although they did not always see eye to eye, Phelps always thought Durocher treated him in a fair manner.

During the 1939 campaign, Phelps became part of the first televised Dodger game. On August 26, at Ebbets Field, the Reds routed the Dodgers 5-2 in front of a small audience of TV viewers. A camera was perched above the catcher for long views; a second camera was beside home plate for close-ups. Babe Phelps was the Dodger backstop that day in Brooklyn. He hit a single and scored a run in the second inning, the first of the Dodger runs ever to appear on the little screen.

Under new manager Durocher, the Bums finished an impressive third in the standings in 1939 and appeared to be on the threshold of contention. A few more changes brought those dreams to fruition. Phelps himself was almost part of the change. A rumor circulated during the winter of 1939 had Babe going to the pennant winning Cincinnati Reds, in exchange for a disgruntled Ernie Lombardi. The deal never did come to pass, but 1940 saw the acquisition of key players such as Joe Medwick and rookie Pee Wee Reese. Phelps at one time roomed with the youngster from Kentucky. He recalled how he once found Reese under the bed after a particularly frightening nightmare. Reese also had a habit of rearranging the hotel room furniture to keep from accidentally falling out of a window.

On the matter of roommates, Phelps made it known to management that he needed a quiet roommate. Unlike the typical ballplayer of the era, Babe did not keep late hours and usually would turn in early to get the rest he needed. Since this sort of a “roomie” was hard to find, Phelps would often be the sole occupant of a hotel suite.

During the season, Babe, Mabel, and young Janet would maintain living quarters in New York so that Babe’s evenings at home were spent with the family. Road travel was by train, and Babe’s favorite pastime was to play bridge (never poker) during the rides to other National League cities. Players were expected to maintain some semblance of a proper dress code. Even in the heat of the summer it was expected that players would be clad in a neat sport coat and tie. The wives would have their own section at Ebbets Field, and they in turn dressed appropriately to cheer on their husband’s performance – it was not uncommon for the ladies to be in heels, hats and even gloves.

On May 7, 1940, the Dodgers embarked on another MacPhail innovation – air travel. While operating as GM of the Reds, MacPhail had experimented with moving the club by air. He now decided that in the modern age of the 1940’s it was time to institute more air flight for the entire team.

After completing a three-game series with the Cardinals, the Dodgers boarded two planes headed for Chicago. Immediately apprehensive, Phelps refused to go on the flight. After some coaxing by Durocher, the big catcher boarded the plane and sat next to the Dodger manager for three harrowing hours in flight. Upon landing, Babe announced that he would absolutely never fly again. On the return trip from Chicago to Brooklyn, Phelps took a train, while the balance of the team flew back to New York. The nickname “Blimp” now became “the Grounded Blimp.” Most of the players started getting used to the idea of air travel. Durocher was all for it and announced that in the future, this was the only way he wanted to go.

The 1940 Dodgers finished in second place, 12 games behind the pennant winning Reds. Phelps appeared in 118 games, hit .295 and slugged a career-high 13 homers. After such an impressive run, the Dodgers spent the winter with thoughts of further improving personnel and finally becoming a contender for the National League flag. It was no secret that Durocher wanted to make a change behind the plate. The Dodger manager sought a better defensive catcher. Phelps was not viewed as an aggressive player on the field. Durocher was aware of this long before he joined Brooklyn. He liked players cut in his own mold: fiery on the field with a win at all costs attitude. The affable Babe Phelps was a nice guy and in Durocher’s mind, “nice guys finish last.”

While attempts to trade the big catcher proved fruitless, MacPhail was able to obtain veteran catcher Mickey Owen from the Cardinals. Owen had a style of play that Durocher sought. He was strong on defense, but the right-handed hitter was not a stellar performer with the bat.

Clearwater was the official spring training site in 1941. The plan was to spend one full month working out in Havana, then head back to Florida and points north at the conclusion of camp. The mode of transportation to Cuba was either by air or boat. The prospect of crossing a desolate 90 miles over the Atlantic was unthinkable to Phelps. He abruptly turned around and left camp. He would ultimately rejoin the club in Florida, but this incident confirmed Durocher’s thinking that Owen would be his number one catcher during the regular season.

The season opened with the Dodgers losing their initial series versus the Giants. Babe Phelps’ ailments included a sore arm that kept him out of the lineup. Then, after beginning to put in some time behind the plate, he broke a finger and was out for a month. It was after the finger healed that he returned to the lineup, pinch hitting, handling some of the catching duties and even hitting clean-up the day before embarking on the fateful road trip west.

The day of the trip, Durocher was pacing the train station – waiting for his lefty-swinging catcher. The veteran backstop told his manager that he was worried about his heart but indicated that he would make the trip. Phelps’ concern for his health and his heart in particular had become common knowledge around the league. It was Phelps’ contention that if his heart did not maintain a proper rhythm of beats, the result could be fatal. Thus he personally would monitor the beating of his heart, sometimes throughout a night that should have been spent in restful sleep.

Phelps never arrived to make the trip with his team. Apparently, Durocher finally reached him by phone before the train left New York. Phelps refused to come over and board the train for the trip, citing health reasons. The catcher’s absence so incensed both MacPhail and Durocher that, while traveling west, they repeatedly attempted to deal the absent receiver to another club. All of this was occurring while the Dodger brass continued to make excuses to members of the press. Chaos reigned on the trip, MacPhail finally deciding to end the speculation by suspending Phelps for his unauthorized absence and fining the veteran catcher $1,000. The big catcher reportedly tried (unsuccessfully) to reach MacPhail in his office the day before the road trip. Upon learning of the suspension, he reportedly packed his bags and traveled with his wife back to their residence in Maryland, deciding this course of action was best for recuperation.

Physicians had previously examined the catcher, and their findings indicated Phelps was basically fine. It was reported in the press that he was a neurasthenic – a person who imagines things. A closer scrutiny of the symptoms of neurasthenia indicates an emotional disorder accompanied by fatigue, a lack of motivation, feelings of inadequacy and psychosomatic symptoms.

In the context of the early 1940s, this was not considered a legitimate set of circumstances for being removed from the lineup – especially in a pennant race.

Former teammate (Fat) Freddie Fitzsimmons, in an interview years later, would comment that some players (e.g. Phelps) could not take the strain of bearing down every day in the heat of a pennant race. Durocher voiced displeasure over his catcher’s actions, declaring that he was “through” with the veteran receiver. Although the Dodger manager would recant in the near future, he essentially was correct that Phelps’ tenure as a Dodger was over.

Durocher’s reversal occurred when he took the matter to the Commissioner of Baseball. Traveling to Chicago, Durocher visited Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in his office on Michigan Avenue, seeking reinstatement of his tardy catcher. Why this change of heart? The Dodgers were legitimately in the heat of a pennant race, and Phelps was a veteran with a decent bat and a left-handed hitter to boot. All of this had value to a manager fighting for the flag. The unsuccessful attempts to trade Phelps meant that the suspended catcher would bring nothing of value by sitting out the season. Certainly Durocher saw more value in at least having him accessible to spell Mickey Owen behind the plate. In this light, seeking a reversal from Judge Landis makes sense.

Durocher probably embellished the facts in relating the story to Landis, but developed the scenario that Phelps’ roommate Lew Riggs had knowledge of the Babe’s concerns about his health, specifically problems with his heart. Landis thought he had a pretty clear idea of what had occurred when Babe Phelps himself sought out the commissioner to plead his case. Upon meeting with Landis, the Judge did most of the talking – almost to the point of leading the witness. Landis asked the Babe if he feared he was having a heart attack. The big catcher answered an emphatic no. When Landis asked about what Riggs had reported to Durocher, Phelps would not confirm any of it and was so non-committal throughout the meeting that the Judge simply had no choice but to let the fine and suspension stand.

The Babe returned home to Maryland, where he sat out the rest of the season, watching from the sidelines as his team streaked toward the pennant, ultimately capturing the National League flag in an exciting race that went right down to the wire. The Dodgers proceeded to lose the 1941 World Series to the rival New York Yankees, a series remembered most for Dodger catcher Mickey Owen’s passed ball that ultimately lead to a Yankee victory in Game Four. The Bronx Bombers would win the Series the next day.

The attention of the country went from the fall classic to the sudden and tragic events of December 7, 1941, as the bombing of Pearl Harbor changed the world and thrust the country into war. Just days later, Brooklyn management traded Babe Phelps, Pete Coscarart, Luke Hamlin and Jimmy Wasdell to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Arky Vaughan. After parts of seven seasons in Brooklyn, Phelps’ tenure there officially came to an end. At the time he was the senior Dodger in terms of service; the last link to the daffiness boys of days gone by was passing into baseball history.

Babe joined former teammate Al Lopez with the Pirates for the 1942 season, sharing catching duties with him. Phelps hit .284 in 95 games, splitting the catching assignment equally with Lopez. The Pirates, under manager Frankie Frisch, finished the ’42 campaign in a disappointing fifth place, far out of contention.

After the close of that season, Phelps was dealt to the Philadelphia Phillies in exchange for another Babe – veteran first sacker Babe Dahlgren. Phelps never did sign a contract or report to his new club. He instead opted to retire, stay in Odenton, and go to work for the railroad. He assisted in the war effort as a dispatcher at the military post in Fort Meade, Maryland.

Home to stay and ever the family man, Phelps forged a pleasant life for his wife and growing daughter. Later he would again participate in local baseball both as a player and manager. In retirement, Babe would often be surprised at how fondly he was remembered by the affectionate Brooklyn fans. Long after Babe retired, a very unscientific poll taken among Dodger fans listed the big catcher as their all-time favorite Dodger backstop. Over the years, Babe would marvel over correspondence from fans with accompanying requests for autographs.

Prior to his passing in 1992, at the age of 84, he was inducted into the Dodgers Hall of Fame, the Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame and the Anne Arundel County Sports Hall of Fame. All of these honors were a testament to his talent on the ball field and his popularity with the fans.

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, 1982

Creamer, Robert W. Baseball and Other Matters in 1941. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books – University of Nebraska Press, originally published by Viking, 1991.

“Daffy Dodgers Monopolize the Headline Again as Majors Open Their Spring Training Grind”. Newsweek. March 2, 1942. No author.

Eskenazi, Gerald. The Lip – Biography of Leo Dorocher. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1993.

Frank, Stanley. “Did the Best teams get in the Series?” Saturday Evening Post. October 1, 1955, pp. 25, 110, 112.

Macht, Norman. Audio tape interview with Babe Phelps.

Meany, Tom. “They Didn’t Hire Him for Laughs.” Saturday Evening Post. March 12, 1949, pp. 110, 112, 124.

The New York Times. June 12-15, 1941. Box scores.

Pietrusza, David. Judge and Jury. South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998.

“Scorecard”. Sports Illustrated. March 20, 1967. No author.

Steadman, John. “Lineup of Legends.” Baltimore Sun Magazine. July 17, 1994, p. 18.

Vitty, Cort. Interview with Janet Engler (daughter of Babe Phelps).

Warfield, Don. The Roaring Redhead. South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1987.

Full Name

Ernest Gordon Phelps

Born

April 16, 1908 at Odenton, MD (USA)

Died

December 10, 1992 at Odenton, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.