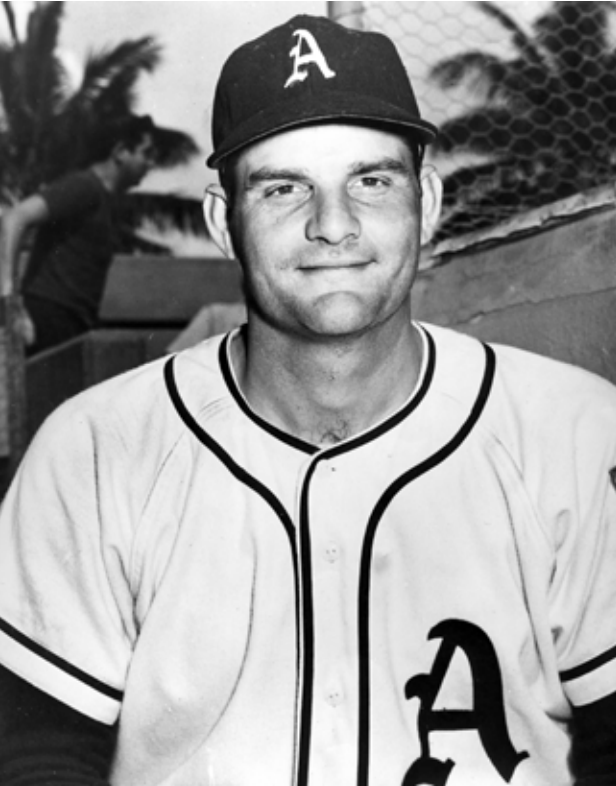

Harry Byrd

Harry Byrd Highway runs west from US 401 for about five miles along South Carolina Route 34/151, and past Darlington Raceway, NASCAR’s first paved superspeedway. The 1.25-mile egg-shaped oval, built in 1950, is a shrine for stock-car racing comparable to what Wrigley Field is for baseball. Many racing fans visiting the Darlington Raceway Stock Car Museum probably ask, “What did Harry Byrd drive?” or “Who was Harry Byrd?”

Harry Byrd Highway runs west from US 401 for about five miles along South Carolina Route 34/151, and past Darlington Raceway, NASCAR’s first paved superspeedway. The 1.25-mile egg-shaped oval, built in 1950, is a shrine for stock-car racing comparable to what Wrigley Field is for baseball. Many racing fans visiting the Darlington Raceway Stock Car Museum probably ask, “What did Harry Byrd drive?” or “Who was Harry Byrd?”

Byrd was, in fact, a Darlington native and the American League Rookie of the Year in 1952, when he had a 15-15 record for the Philadelphia Athletics, and compiled a 3.31 ERA in 228⅓ innings. He was a local boy who made good, but returned home after his professional career was over. He compiled a lifetime record of 46-54 in seven seasons in the major leagues, and 120-129 in 12 seasons in the minor leagues.

Harry Byrd was born on February 3, 1925, in Mont Clare, South Carolina, an unincorporated village about seven miles northeast of Darlington. He was the youngest of six children – two girls and four boys – born to James Curtis Byrd Sr. and Annie Tuttle Byrd. His father, like most folks in Mont Clare, made a living as a laborer in logging and pulp lumber operations, and raised chickens for food and extra income. Later he became a superintendent in a sawmill.

Mont Clare had a grammar school for grades one to seven, with two teachers. Harry and a group of nine or 10 boys with ages in an approximate four-year range learned to play baseball together at the school. They played ball all the time. One of the boys later explained that the only two things to do at recess were see-saw or play baseball. “After all,” he said, “the interest span for see-sawing is very limited for boys that age.”1 The boys started playing games with nearby villages when they were about 10 years old. Harry was chosen as the pitcher because he won the team’s long-throw contest. There were no official leagues, and games were arranged on an ad-hoc basis. The coach drove the players to away games in a wagon towed behind his car.

Harry enrolled at Darlington St. John’s in eighth grade. He started logging with his father when he was 12 years old, and the hard labor turned him into an imposing physical specimen, with wide shoulders and well-developed muscles. He played football and baseball at St. John’s High School. As a junior Byrd pitched St. John’s to the 1942 State Class-A Championship. Legendary Columbia High School coach H. B. Rhame called Byrd “the best high school pitcher he had ever seen.”2 Five players from the old Mont Clare youth team were on the squad – Harry, his older brother, Wesley, Tom Tyson, Robert Richardson, and Tom Kleven.

Later in 1942 Harry’s father moved the family to Pelzer, South Carolina, probably to take a job in textile mills that were booming to fill wartime orders. Pelzer was an unincorporated village in northern Anderson County, just south of Greenville. Harry pitched for the Pelzer Bears town team and a Junior American Legion team from Greenville in the spring of 1943. He graduated with the Pelzer High School Class of 1943 on May 24, and enlisted in the Army on June 8. He was assigned to an airborne division, but then was transferred to the 567th Anti-Aircraft Battalion, which arrived in Europe on December 20, 1944. Byrd was discharged on February 3, 1946, and returned to his family, now back in Mont Clare. He still had the desire to play baseball. “There wasn’t much time to play ball in the Army,” he declared. “I played a little softball now and then, but it didn’t do anything for me. I began to wonder whether I’d be able to pitch again.”3

He did not have to wait long to find out. Johnny Stokes, Darlington County sheriff and Harry’s Legion coach, had alerted Philadelphia Athletics scout Ira Thomas about Byrd back in 1941 and 1942. Thomas signed the burly right-hander shortly after he came home, and the A’s assigned him to their Martinsville (Virginia) farm team in the Class-C Carolina League.

Byrd had a 15-12 record for sixth-place Martinsville, but had control problems all year. He walked 108 batters in 236 innings, and finished with a 4.77 ERA. Harry returned to Mont Clare after the season, and worked in local logging operations, a practice he maintained throughout his baseball career. (Major-league sportswriters later frequently referred to him as a “lumberjack” or “woodsman.”) He also met Mary Lee Lyles, a girl from nearby Hartsville. They were engaged before Harry returned to baseball in early 1947, and were married in October.

Byrd spent the next two seasons with Savannah (Georgia), the A’s farm team in the Single-A Sally (South Atlantic) League. He had solid, but unspectacular results: 16-13, with a 5.56 ERA in 1947, and 15-15, with a 4.09 ERA in 1948. He continued to have control problems and was overshadowed by other young pitchers in the A’s organization: Lou Brissie, Carl Scheib, Alex Kellner, and Bobby Shantz. Brissie was 24 years old in 1948, Byrd and Kellner were 23, while Shantz was 22, and Scheib only 21.

Savannah sold Byrd to Buffalo of the Triple-A International League in October 1948. It is unclear whether the Athletics had given up on him, or felt they had too many young pitchers in their organization, or if they simply wanted to give him experience in a tougher league. (They owned no farm teams above Class A.)

Byrd got off to a good start in the Buffalo spring training camp in Waxahachie, Texas. Bisons manager Paul Richards called Byrd the best rookie pitcher in his training camp, and Byrd said Richards taught him how to pitch. “Before he took hold of me, I was just a thrower. I still had a lot of rough spots, understand, but after three weeks under Richards I felt I had a chance to go somewhere in baseball.”4 The relationship was strained when Harry learned his father had suffered a heart attack. He asked the team for a leave to go home to care for his father’s 400 chickens. Team officials figured Byrd was just homesick and refused his request. Byrd went home anyway, and Buffalo suspended him. Byrd later regretted his decision. “I was a fool to leave the Buffalo team in spring training,” he said in a 1952 interview. “But I could think only of my father at the time. He recovered, and is in fairly good health now. But that season almost wrecked me.”5

Back home in Mont Clare, Byrd contemplated quitting Organized Baseball, and soon began pitching for his old Legion coach, Johnny Stokes, with nearby Hartsville in the semipro Palmetto League. When Buffalo offered to reinstate Byrd, Stokes talked him into accepting. He was optioned in mid-August to Savannah, where he had a subpar 2-8 record with a 4.67 ERA in 54 innings of work.

Byrd was still under contract with Buffalo, which had moved its 1950 spring-training base from Texas to Avon Park, Florida. He was brought to the A’s camp in West Palm Beach early in spring training to pitch batting practice and impressed Hall of Famer Mickey Cochrane, who had just been hired as one of the team’s coaches. “He’s big and fast,” Cochrane said. “He’s strong and has a good fastball. His curve is fair, but getting better. I think he’s a helluva prospect.”6 Thanks to sore arms by three expected starting pitchers – Alex Kellner, Dick Fowler, and Joe Coleman – the Athletics purchased Byrd’s contract from Buffalo and he found himself on the Opening Day roster.

Byrd’s first major-league game was forgettable. He entered the game in the top of the ninth inning against Boston at Shibe Park on April 21, with the Athletics trailing 4-1, and gave up a grand slam to Vern Stephens. He was optioned to Buffalo in June after making six short relief appearances. Byrd struggled to a 4-9 record with the last-place Bisons. His 6.75 ERA (in 108 innings) was the highest in the International League for pitchers who worked more than 100 innings.

Nevertheless, the Athletics placed Byrd on their 1951 spring-training roster. He saw little action once spring-training games began and was optioned to Single-A Savannah once again, but was encouraged by advice given to him during training camp by the A’s new pitching coach, future Hall of Famer Charles “Chief” Bender. “It was the Chief who encouraged me to throw side-arm, my natural style,” Byrd said in a 1952 interview.7 He had been a side-armer growing up, but professional pitching coaches had drilled him on throwing straight overhand. “He needed to wind up in order to get anything on the ball up top,” Bender recalled. “But I noticed that when he threw from down near his chest, he had speed to burn.”8 Byrd had a solid season at Savannah, with an 18-14 record and a 3.59 ERA in 248 innings pitched. He thrived on the heavy workload.

The Athletics seemed to have the nucleus for a strong team coming into spring training in 1952. After finishing above .500 three seasons in a row, 1947-1949, they had a miserable 52-102 record in 1950, but in 1951 under new manager Jimmy Dykes, their first new manager in 50 years, the team finished 18 games better at 70-84. First baseman Ferris Fain led the league in batting with a .344 average, outfielder Gus Zernial led the league with 33 home runs and 129 RBIs, and Bobby Shantz became the team’s ace starter with an 18-10 record.

Byrd felt good about his season at Savannah, was in good shape after an offseason of hard physical labor in a sawmill, had a good relationship with A’s pitching coach Chief Bender, and was looking forward to reporting to 1952 spring training. He was given more chances to pitch in early exhibition games than he had in 1951 and made the Opening Day roster.

Byrd was used sparingly early in the season. He impressed Dykes with a six-inning relief job against Washington on May 10 when he came in to replace an injured Morrie Martin. Dykes rewarded Byrd with a start against the Browns at St. Louis on May 14, but he lasted only three innings, and didn’t get another start until May 27. Byrd came through with a complete-game 7-3 victory – his first major-league win – over the Red Sox at Boston, and Dykes put him in the starting rotation for the rest of the season. The team was 31-37 at the All-Star break, and in sixth place. Shantz was 14-3 and almost single-handedly keeping the team competitive. Byrd was 5-7 overall, but 4-5 as a starter.

The A’s were 48‑38 after the break and finished the season in fourth place. Shantz continued his brilliant season with a 10-4 second-half record, while Byrd was 10-8. Byrd was a workhorse, starting 19 games, relieving in three others, and pitching 155⅔ innings … and asking for more work. “I’ve been lucky, I guess,” Byrd drawled. “Never had a sore arm. My arm’s been tired, understand, but never sore. Luck, I guess.”9

Byrd started five games with only two days’ rest. Two came late in the season. He beat Boston on August 28, giving up three earned runs in eight innings, and on August 31, in the same series in Philadelphia, he shut out the Red Sox 2-0. Then, on September 3 he pitched a one-hit shutout to beat the Yankees, 3-0.

Byrd finished the season with a 15-15 record. He could have been 17-13, but he lost 1-0 at Cleveland on September 11 and 1-0 at New York on September 21. His ERA at the All-Star break was 4.46 in 72⅔ innings pitched, but his second-half ERA was 2.78, bringing his season’s average down to 3.31. Byrd gave a lot of credit for his success to Bobo Newsom, the 19-year veteran pitcher the A’s signed in June after his release from the Washington Senators. Newsom was from Hartsville, just a few miles down the road from Darlington, and the two had a lot in common. “I never could have done it without Newsom,” Byrd volunteered. “He helped me a lot. Bobo was the first to notice that I was rearing back so far that I was letting go of the ball too soon.”10

The A’s had a lot to feel good about – Ferris Fain won his second consecutive batting title with a .327 average; Gus Zernial had another good year, with 29 home runs and 100 RBIs; and Bobby Shantz was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Byrd and his family shared a home with Everett “Skeeter” Kell (younger brother of future Hall of Famer George Kell) and his family during the season. A’s officials suggested he should stay in Philadelphia over the winter to cash in on his reputation, but he moved back to Darlington. “Can’t do it,” he said. “You can’t go huntin’ or fishin’ in Philadelphia like you can down home.”11 More than 200 local supporters attended the Darlington Lions Club “Harry Byrd Night” on October 13. Chamber of Commerce president Kenneth James presented Byrd with a repeating shotgun from the Lions Club. “I hope your eye is as keen on partridge as it is on home plate,” he said.12

In late November the Baseball Writers Association of America announced they had voted Byrd the 1952 American League Rookie of the Year. Byrd tallied nine votes to eight for catcher Clint Courtney of the Browns and seven for catcher Sammy White of the Red Sox. (Three writers from each city in the league served as the electors.) It was a mild surprise. The Sporting News had selected Courtney as Rookie of the Year in its September 24 edition, but it was the third year in a row its choices differed from the official BBWAA voting.

A reporter from nearby Florence caught up to Byrd and his wife, Mary Lee, at a cold Friday-night high-school football game on November 21 to ask him about the award. He wrote that “There probably wasn’t a more surprised man in Darlington yesterday than Harry Byrd. He still wore that dazed look late last night, hours after he had been informed of his selection as the American League’s ‘Rookie of the Year’ for 1952.”13 Byrd said he didn’t think he had a chance to win the award, but seemed more interested in the game between bitter rivals Darlington and Hartsville. Asked what immediate plans he had, Byrd said he had a deer hunt Saturday morning and would be hunting squirrels in the afternoon … just like many other men in the area.

Byrd changed his offseason plans a little, however, and decided to do a little less work in the sawmill. In August he had speculated that the hard physical labor tightened up his muscles too much. “But next winter I think maybe I’ll quit a month earlier, and do a lot of runnin’. I’ve always been slow gettin’ started, and I believe maybe all that sawin’ may tighten me up. I know I’ve always had trouble gettin’ loose.”14 Probably because of the reduced hard physical labor, Byrd came into spring training overweight. Byrd claimed it was only 10 pounds, but manager Jimmy Dykes said it was 20 or more. Harry’s weight was a sore spot between the two all season.

The A’s figured their starting pitching would be strong, and general manager Art Ehlers had made a big trade in December to bolster their offense. The A’s traded their two-time batting champ Ferris Fain and minor-league infielder Bobby Wilson to the Chicago White Sox for Eddie Robinson, a three-time All-Star who had 29 HRs and 117 RBIs in 1951 and 22 HRs and 104 RBIs in 1952, Joe DeMaestri, and Ed McGhee.

The A’s closed out April at 7-6, a far cry from their disastrous 1-8 start in 1952. Manager Jimmy Dykes took advantage of two open dates and three rainouts to start his aces Shantz and Kellner in 10 of the team’s first 17 games. Byrd started three times. The team was 10-7 and in third place after a doubleheader sweep of Chicago on May 3, but then lost seven straight and fell to seventh place. They would remain in sixth or seventh the rest of the season.

Byrd hit bottom on May 10 when he failed to complete the second inning in an eventual 8-0 loss to the Senators. He was 1-4 at the time, with a 6.30 ERA, but steadily improved his record to 9-10 and a 4.20 ERA at the All-Star break. Byrd was a consistent arm for Dykes on a pitching staff full of injuries, including 1952 AL MVP Bobby Shantz, who tore a tendon in his shoulder on May 21. Alex Kellner missed parts of June with shoulder soreness, then fractured a finger on his left hand on August 26 and was lost for the season. Carl Scheib had persistent arm troubles and started only eight games all season

Thus, Dykes had to look for number one and two starters as well as number four. The one constant was Harry Byrd, strolling to the mound every three or four days, sometimes less. Dykes started Byrd three times with two days’ rest in the second half, and once, on September 2, with only one day of rest after a short, four-inning start on August 31.

Byrd beat the Indians 9-3 on July 18, his first start after the All-Star break, pulling his record even at 10-10. But then his season imploded. He lost nine games in a row, and started five others during that streak where he had no decision. He finally broke the streak with a 2-0 shutout of the Browns on September 13. The A’s were in collapse, as well, with a 5-22 record from August 15 to September 9.

Byrd suffered his 20th loss in his last start of the season, on September 22 when the Yankees knocked him out of the box with six runs in 1⅔ innings. He finished with an 11-20 record and a 5.51 ERA in 236⅔ innings pitched. His second-half record was 2-10, with a 7.46 ERA.

It is fair to ask why Dykes kept writing Byrd’s name in the starting lineup. One answer is that he had no choice – the injuries to Shantz, Kellner, and Scheib left him no other options. Another answer is that Dykes and the Athletics still believed that Byrd had major-league stuff. Other teams in the league believed it, too. As soon as the season ended, the league’s scribes began speculating on possible trades, frequently mentioning Byrd. The New York Yankees had an aging pitching staff: Allie Reynolds (36 years old), Vic Raschi (34), Eddie Lopat, (35), and Johnny Sain (35). Byrd was the Yankees’ first choice in the trading marketplace, but Boston, Chicago, and Cleveland were also seriously interested in him, if for no other reason than to keep him away from New York.

There were big changes in the A’s front office on November 2 when Art Ehlers left to become general manager for the new owners of the St. Louis Browns, who were moving the franchise to Baltimore. Connie Mack’s sons Roy and Earle quickly took control of the team and signed infielder Eddie Joost to replace Jimmy Dykes as manager. Dykes was offered a front-office job, but negotiated a release and soon was made manager of the Orioles.

Joost was realistic about the team’s future. “I see no first-division possibilities as we now stand. We have to make some changes – and we will. We’ll trade anybody except Bobby Shantz and maybe Harry Byrd. …”15 He voiced the majority opinion on Byrd, saying that “most people agree that few – if any – have as much on the ball as Byrd.”16

However, the Athletics and Yankees announced a big 13-player trade on December 16. The A’s sent Byrd, Eddie Robinson, Tom Hamilton, Carmen Mauro, and Loren Babe to the Yankees in exchange for Vic Power, Bill Renna, Don Bollweg, John Gray, Jim Robertson, Jim Finigan, two additional players to be named later, and $25,000.17 A’s beat writer Art Morrow wrote that obtaining Byrd and the slugging Robinson practically guaranteed another pennant for Casey Stengel: “ ’Twas the week before Christmas, chuckled New Yorkers, and Santa Claus dropped in early at Yankee Stadium.”18

The Yankees dismissed worries about Byrd’s physical condition. “Byrd is a good, strong pitcher,” Stengel said. “He wasn’t in the best of physical shape much of last season, but did not have a sore arm. He’s experienced and strong and should be a topflight pitcher.”19

The Yankees brought Byrd to New York for a physical in early January. Ordinarily, players are permitted to take physicals in their hometowns, but the team wanted to talk to him about his conditioning. Byrd tried to downplay his weight, insisting that working in a sawmill after the season had already brought his weight down 10 pounds, from 218 to 208. When asked in an interview if he gained weight because he had lost interest over the A’s poor season, Dan Daniel wrote, Harry protested. “No, it wasn’t that. Not exactly.”20 When asked to clarify, Byrd said, “I don’t want to say what it was.”21

Byrd’s reticence and awkwardness gave him a bad reputation with the press, even though his temperament could simply have been the natural result of his rural upbringing. The front-page story in the January 6, 1954, issue of The Sporting News reported on rankings of players on each team by major-league writers. There were 44 categories, ranging from “fastest runner” to “best dressed” to “best all-around athlete.” Byrd was cited as “most temperamental,” “least cooperative with writers,” and “worst dressed.”22 Others were more forgiving. In November 1957, for example, Detroit general manager John McHale claimed many bad reputations were overexaggerated. “We found that with Byrd. Nobody wanted him a year ago because of reports on his behavior. … He gave us less trouble than anyone on the club.”23

Byrd later laid the blame on Jimmy Dykes for pitching him too much in batting practice and making him run too much during the 1953 season. Dykes made a sharp reply. “He wasn’t in shape and I was determined to get him in shape. Too many players are satisfied today to coast along. They don’t have enough drive. I did Byrd a favor and he doesn’t know it. In fact, he asked to pitch batting practice. Now he blames it on the manager, claims it was too much. That’s the bunk.”24

The Yankees sold longtime ace Vic Raschi to the Cardinals on February 23, 1954, opening a spot for Byrd in the rotation. Tom Morgan was also expected to compete for a starting job after spending a year and a half in military service.

Byrd had bad luck while losing his first three starts. He gave up only three earned runs in 17 innings pitched, but the Yankees did not score a run when he was on the mound in those games. He finally won his first game on May 9, pitching seven innings in a 7-4 victory over the Athletics, but tore a muscle in his side in a game on May 14 and sat out two weeks. Then he was plagued several times by attacks of hives, caused by a reaction to some antihistamine shots. Byrd had a 4-5 record, with a 3.96 ERA in 61⅓ innings pitched, at the All-Star break, and had become a spot starter. Six of his 11 starts had been in doubleheaders, when extra starting pitchers were required.

Byrd pitched a complete-game shutout to beat Detroit 6-0 on July 18, his first start after the All-Star Game. In his next start, on July 22, he pitched another complete game to beat Chicago, 11-1. Both games, not surprisingly, were in doubleheaders, but he had worked his way back into the starting rotation. On August 28 he started and pitched six innings in a 4-2 win against Detroit, bringing his overall record to 9-7. Since the All-Star Game he had started nine games, completed four, with a 2.05 ERA and a 5-2 record. At the time the Yankees were 88-40 and 3½ games behind Cleveland, and appeared to be on their way to winning at least 100 games for the first time since 1942.

But Harry made only two appearances the rest of the season. Rookie Bob Grim, on his way to a 20-6 record and Rookie of the Year honors, and Whitey Ford each started five of the team’s final 26 games. Byrd’s fate with the Yankees was foretold when Tommy Byrne, a regular starter for the Yankees in 1949 and 1950, was purchased from Seattle of the Pacific Coast League on September 3, and started five games in September.

Byrd was not surprised when he found that he was traded to Baltimore in a multiplayer deal on November 17, 1954. Harry and Jim McDonald, Willie Miranda, Hal Smith, Gus Triandos, Gene Woodling, and four players to be named later were sent to the Orioles in return for Billy Hunter, Don Larsen, Bob Turley, and four players to be named later. Byrd said he was happy to be traded. “Not that I’m sore at the Yankees or at Casey Stengel or at the organization,” he said. “It’s not that. It’s just that I have to pitch regularly to be effective and I didn’t get that chance to pitch regularly with the Yankees.”25

Byrd started well at Baltimore in 1955, beating the Senators 3-0 on April 23 with a three-hit shutout, but the Orioles placed him on waivers and Chicago picked him up on June 15. He shut out the Senators again, giving up only four hits in a 7-0 win on June 23, but was not very effective the rest of the season. His combined record was 7-8, with 20 starts and a 4.61 ERA in 156⅓ innings pitched.

Chicago traded Byrd to Detroit on May 15, 1956, along with Bob Kennedy and Jim Brideweser in exchange for Fred Hatfield and Jim Delsing. He had pitched only 4⅓ innings in three games at the time. Detroit sent him to their Charleston farm team in the Triple-A American Association, where he spent the rest of the season. Used as a starter there (21 of 24 games) his record was 8-9, with a 4.06 ERA.

Byrd decided to play with Centauros de Maracaibo in Venezuela’s four-team Occidental League over the winter to build up his arm strength. The league played a 57-game schedule from December 1956 to February 1957. Byrd had an 11-7 record with a 2.36 ERA for the third place (28-29) Centauros, and got a lot of work, pitching 156 innings.26

Detroit assigned Byrd to Charleston again in 1957. After several games he was sent down to the Tigers’ Birmingham farm team in the Double-A Southern Association. He was recalled by the Tigers in late June, and pitched two innings in relief only hours after he joined the team in Washington. Although he was a starting pitcher at Charleston and Birmingham, he became a short reliever in Detroit. He pitched in 37 of the team’s 89 remaining games, and had a 4-3 record and a 3.36 ERA in 59 innings pitched.

Byrd appeared to be a key man in Detroit’s bullpen plans for 1958. He was placed on the Detroit 40-man roster in January, but was the last man cut in spring training and returned to Birmingham. In July, Detroit sold the 33-year-old’s contract to Omaha (a Cardinals farm team) in the Triple-A American Association. “Youth has the right of way in the Tigers’ farm system,” said an article in The Sporting News. “When veteran Righthander Harry Byrd was sold by the Birmingham Barons (Southern) to Omaha (American Association), it was announced here [Detroit] that the move was made to give young pitchers more work. Byrd, whose bull-pen work was vital in the Tigers’ fourth-place finish last season, had an 8-11 mark at Birmingham.”27

Harry never made it back to the big leagues. He had an 8-16 record for Miami in the Triple-A International League in 1959, and pitched for Miami and for Portland (Oregon) of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 1960. He retired in 1961, after pitching in 21 games for Portland and Hawaii in the PCL.

When it was over, Byrd returned to his roots back in Darlington, where he worked, hunted, and fished with folks he grew up with. He was active in the local VFW, hunters’ clubs, and several baseball alumni organizations, and was a member of the Wesley Memorial United Methodist Church. He returned to work in the lumber business and eventually worked for more than 10 years as a foreman with the R.E. Goodson Construction Company, whose origin was building roads for logging operations. He played some more baseball, too, as player-manager for the Darlington Rebels in the semipro Border Belt League (consisting of eight towns on either side of the South Carolina/North Carolina border).

Harry died after a short illness on May 14, 1985. He left behind his wife, Mary Lee, and two daughters, Pamela and Vicky.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com, newspaperarchive.com, newspapers.com, and retrosheet.org, as well as:

Cobb, Bill, and Gene Welborn. Memories of Pelzer 1881-1950 (Bountiful Utah: Family History Publishers, 1995).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997).

“A History of the 567th Battalion.” 567thbattalion.com, accessed June 1, 2017.

Anderson County Library, Anderson, South Carolina 29621.

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York, player file for Harry Byrd.

Darlington Historical Commission, Darlington, South Carolina 29532.

Hennepin County (Minnesota) Library: Ancestry Library Edition; ProQuest Historical Newspapers, the New York Times; and ProQuest Newsstand.

Notes

1 Arthur Richardson, “How Harry Byrd Came to Be a Major League Pitcher,” Darlington News & Press, September 27, 1990: One-C.

2 “Statistics About Darlington Class A Baseball Champs of South Carolina,” Florence (South Carolina) Morning News, May 31, 1942: 5.

3 Edgar Williams, “1953’s for the BYRD!,” Baseball Digest, November 1952: 21.

4 Williams: 22.

5 Ibid.

6 Art Morrow, “Wyse Posts First Win – Gets Connie to Up Pay Terms,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1950: 16.

7 Art Morrow, “Hats Off,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1952: 22.

8 Ibid.

9 Art Morrow, “ ‘Get Lost for Awhile,’ Dykes Tells Bobby in Effort to Ease Tension on A’s Ace,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1952: 9.

10 Art Morrow, “Dotted Line Dash of Athletics Finds Bobo Out in Front,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1952: 8.

11 Williams: 23.

12 Arthur Strickland, “Harry Byrd Honored by Darlington Friends,” Florence (South Carolina) Morning News, October 14, 1952: 9.

13 Bob Weirich, “Surprised Byrd Says, ‘Who, Me?’ at AL Rookie-of-Year Selection,” Florence Morning News, November 22, 1952: 1.

14 Morrow, “ ‘Get Lost for Awhile.”

15 Art Morrow, “Joost Plans Player Changes, Few Rules,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1953: 3.

16 Ibid.

17 Daniel, “Champs Now Eyeing Turley or Larsen in Oriole Trade,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1953: 9.

18 Art Morrow, “A’s Given Eight, Including Power, Bollweg and Renna,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1953: 9.

19 Dan Daniel, “Champs Now Eyeing Turley.”

20 Dan Daniel, “Byrd, First Yank to Sign, Denies He’s Overweight,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, January 14, 1954.

21 Ibid.

22 C.C. Johnson Spink, “The Low-Down on Majors’ Big Shots,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1954: 1-2.

23 Watson Spoelstra, “Swap Sewed Up by McHale in Frank’s Absence in Cuba,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1957: 7.

24 “ ‘Byrd Out of Shape,’ Snaps Dykes to ‘Overwork’ Charge,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1954: 20.

25 Van Newman, “ ‘Great to Be Yank, But Not Once-a-Week Kind!’ – Byrd,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1955: 13.

26 Olaf E. Dickson, “Dickens, Hoskins Occidental Loop Bat, Hill Leaders,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1957: 30.

27 “Byrd Sale Points Up Bengal Emphasis on Kids in Chain,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1958: 17.

Full Name

Harry Gladwin Byrd

Born

February 3, 1925 at Darlington, SC (USA)

Died

May 14, 1985 at Darlington, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.