Clint Courtney

Scrap Iron: the punchy, evocative nickname fit Phil Garner well in the 1970s and ’80s — but it fit catcher Clint Courtney even better a generation before. The punchy part was one reason. Journalist Bob Addie wrote in 1959, “Clint put his aggressive temperament to work several times and was involved in some notable fisticuffs during his early career.”[1] Yet that was just one aspect of The Toy Bulldog’s toughness. Author John Daniel described him as “a man composed, according to my father, solely of bruises, knitted bones, and sheer grit.”[2]

Scrap Iron: the punchy, evocative nickname fit Phil Garner well in the 1970s and ’80s — but it fit catcher Clint Courtney even better a generation before. The punchy part was one reason. Journalist Bob Addie wrote in 1959, “Clint put his aggressive temperament to work several times and was involved in some notable fisticuffs during his early career.”[1] Yet that was just one aspect of The Toy Bulldog’s toughness. Author John Daniel described him as “a man composed, according to my father, solely of bruises, knitted bones, and sheer grit.”[2]

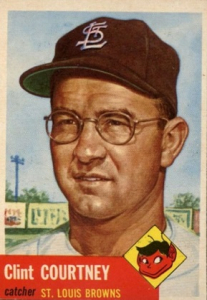

In past eras baseball had more “characters,” and Courtney exemplified the breed. Miles Wolff, who owned a string of minor-league ball clubs over three decades, had Clint as a manager at Savannah in the early 1970s. Wolff said, “Everybody in baseball has their own story about ‘Scrap Iron’ Courtney, a squat, bespectacled catcher who was known to like a beer now and then.”[3]

In Courtney’s best obituary, however, sportswriter Milton Richman gave a more fully rounded picture of his friend: “Clint Courtney was only tough on the outside. Inside, he was a soft, compassionate human being, more outspoken than he should’ve been at times perhaps, but with uncommon understanding and honest concern for others which always transcended the rough exterior he chose to show the world.”[4] This empathy helped him become a successful minor-league manager. Had Clint not passed away so young — he was only 48 years old — he might have realized his ambition of managing in the majors.

As a player, Clint wasn’t elegant, but he got the job done, especially as a field general. At his best, he was a good line-drive hitter, though he never had a great deal of power. His 11 years in the big leagues also featured two intriguing positional footnotes. Clint gets credit (with an element of doubt) as the first receiver in the majors to wear glasses behind the plate. Nine years later, in 1960, he was the first to wear the giant mitt that Paul Richards developed to help handle knuckleball pitchers.

Clinton Dawson Courtney was born on March 16, 1927, in Hall Summit, Louisiana. This village’s population was just 264 as of 2000, and it was not much more when Clint was a boy. It is located in Red River Parish, in the northwestern part of the state, about 14 miles north of the parish seat, Coushatta, and roughly 40 miles southeast of Shreveport. Clint always spoke with a pronounced Southern drawl. St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg called it “a treble, singsong voice that is as deceptive as his mild appearance and smallish size.”[5]

Clint’s father, C.D. Courtney (the initials did not stand for anything), was a tenant farmer. “Cotton picking, not baseball, was the first trade the youngster learned,” wrote journalist David Condon in a 1955 feature.[6] C.D. separated from Clint’s mother, Ethel Murray Courtney, when the boy was only three or four years old. His sister Fleta went with Ethel, but Clint stayed with C.D., who married a woman named Gladys Woods and had two other daughters, Cecil and Jo.

It was a hardscrabble life for the Courtney family. In 1958 Clint said, “I was so poor as a boy, my shoes were so bad that I could step on a dime and tell you if it was heads or tails.”[7] In 2010, Clint’s sister Jo Lawson said, “There was always plenty of food on the table, though. It may not have been exactly what we wanted, but we didn’t go hungry.”

Courtney went to school in Hall Summit for grades 1-5 and in the neighboring village of East Point for grades 6-8, but the family then moved to Arkansas. (Several sources indicate that they spent time in Alabama, but this is incorrect.) “We needed money,” said Jo, “so our daddy went to work in the oil fields. Clint graduated from Standard-Umstead High School in Smackover, Arkansas. I believe he was a member of the last class from that school. There were 11 grades, not 12.”

After graduating, young Clint joined his father in the Smackover oil patch. He then went to work as a welder in a shipyard in Orange, Texas. Clint’s obituary in the New York Times said that he did not play baseball until he entered the U.S. Army, but this is one of several inaccuracies in that article. A Sporting News feature by L.A. McMaster in May 1952 noted that his introduction to the game came in the shipyard at age 17.[8] That too is a misconception. It would seem most likely that an American country boy in those days played baseball growing up, and Jo (who idolized her big brother) confirmed that indeed he did. “He was often found playing on sandlots in Red River Parish.” Clint was short and did not appear athletic — “he could pass for the fellow working at a gas station.” Still, he was also an All-State basketball player in high school, though Jo points out, “It was probably the lowest class in the state, since Standard-Umstead was a small school.”

In 1944, Clint was drafted into the Army. His first stations were Camp Robinson and Fort Chaffee, Arkansas. Fort Chaffee’s team played in the 1945 National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. After that, he served in Korea, the Philippines, and Japan, where he was a member of the Army of Occupation. Courtney was an outfielder at first, but then went behind the plate. David Condon’s article further supported the idea that Clint had played ball before joining the Army. It said, “Along the route, Courtney had developed into a proficient ballplayer.”[9]

Accounts also vary widely as to when Courtney began wearing glasses. The McMaster story said it was while he was in Korea, but Bob Broeg said it was later, in the minors. Jo Lawson’s family knowledge makes intuitive sense: the need arose from his welding job. At any rate, Clint found he had trouble with high twisting foul pop-ups. A vision check revealed that he had astigmatism, and so he also needed specs to play. There was precedent among catchers in college ball and the minor leagues, and (contrary to the accepted wisdom) a big-league catcher — possibly Mike González — may have worn glasses before Courtney.[10] Clint’s lenses were shatter-proof and he taped the frame to the sides of his head.[11] Even so, his collision-prone style led him to run through a dozen pairs by 1958.[12]

Shortly after Courtney was discharged in 1947, the New York Yankees signed the lefty-swinging catcher. The scout was Atley Donald, who stayed in the Yankee organization after pitching his last game in 1945. He visited Clint on the family farm (C.D. had returned from Arkansas) and they worked out the deal. Clint received an $850 bonus, “$250 of it cash and $600 contingent on an impressive showing. Courtney lost no time in making the impressive showing.”[13]

At age 20, Courtney’s first assignment was Beaumont in the Double-A Texas League. After four games there, he went to Bisbee, Arizona in the Class C Arizona-Texas League, where he hit .319 with 5 homers in 114 games and was named to the league’s All-Star team. His manager was Charlie Metro, who later became part of the “College of Coaches” for the Chicago Cubs in 1962 and managed the Kansas City Royals at the beginning of 1970. In his memoirs, Metro told an array of stories, including how he had to fine Clint — “the hardest-headed ballplayer I ever saw” — after the catcher started a fire in his hotel room. Courtney, who was still wearing his olive drab military underwear, was reluctant to fork over the discharge money he had not spent.[14]

Growing up poor obviously affected Courtney. In 1952, he told Bob Broeg, “Hell, guys ought’a be tickled to death to play ball in the big leagues. They don’t know how good they got it. Those who complain ought’a try pickin’ cotton the way I did. That’d learn ’em. They’d come runnin’ back in a hurry.”[15] Later, in 1954, American League sportswriters named him for “Best Business Sense” and being “Least Generous” on the Baltimore Orioles — as well as “Most Serious Minded,” “Most Serious on the Field,” and “Worst Dressed.”[16]

Clint was something of a junior Ty Cobb: furiously competitive and fond of coming in with spikes high. The 1947 season was also notable for the genesis of his feud with an even more pugnacious player: Billy Martin, then with Phoenix. Martin remembered that Courtney slid into second base, spiking the hand of playing manager Arky Biggs, who then broke his hand on Clint’s face. After that there was bad blood between Clint and Billy. “I was always waiting to get Courtney,” Martin told author Maury Allen.[17]

After the 1947 summer season ended, Courtney enjoyed his first winter-ball experience in Mazatlán, Mexico. The opportunity came courtesy of Charlie Metro, who had also been invited. As Metro related, Clint successfully hustled the locals at ping-pong.[18]

Courtney started the 1948 season with Beaumont but was optioned to Augusta (Class A) in late April. Augusta then traded him to Norfolk (Class B) in late July. He didn’t hit much that year (.243 with just one homer overall) and so he remained in Class B during 1949. With Manchester and Norfolk, he picked up to .302 with 10 homers.

In the winter of 1949-50 Courtney led the Mexican Coast League in batting at .371 in 38 games. At age 22, he also got his first chance to be a manager. He was one of two skippers for the Guaymas Ostioneros that season. The Oystermen dismissed José Luis Gómez after a poor first half of the season, and Clint turned the club around in the second half.

For 1950 Courtney earned promotion to Beaumont once more. He was one of two unanimous choices for the league’s All-Star Game, hitting .263-4-79 and standing out as a leader. His manager, Rogers Hornsby, took a liking to the hardnosed backstop. Clint also made an impression on Frank Lane, general manager of the Chicago White Sox. Beaumont beat the White Sox in an exhibition game, led by “the cocky catcher’s chatter and spirit.” Lane told Hornsby, “That Courtney’s an old-time chew-tobacco type of player, like Nellie Fox and Burrhead Fain. There aren’t enough of ’em left in the majors. Too bad the little son-of-a-gun wears glasses.” Hornsby responded, “Glasses or not, Courtney’ll fight his way into the big leagues.”[19]

Hornsby managed Clint again for the Ponce Leones in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Courtney was not among the league leaders in any category, but he made a tremendous impression on the fans of Puerto Rico. In the balloting for the two all-star teams, one made up of local players and the other of imports, the fiery catcher received more votes than anyone else, native or otherwise.[20]

According to Courtney’s family, Yankees general manager George Weiss tried to talk Clint out of playing winter ball. Weiss proposed that he work instead for the team’s co-owner, construction magnate Del Webb, because the pay would be better. Clint responded that no general manager ran his life. He played.

Courtney advanced again in 1951. He did well in spring training — New York sportswriter Dan Daniel called him “an interesting newcomer” and “likely to stick.” In fact, he was on the big club’s roster as the season started. After just a couple of games the Yankees optioned him to their Triple-A team at Kansas City. As the starting catcher for the Blues, Clint played and hit well again (.294-8-35 in 105 games). Among other things, in a June game against Milwaukee, he knocked out two of Johnny Logan’s front teeth in a “bump” at second base.[21] He also got into a scrap with future Phillies manager Danny Ozark after a play at the plate.

Toward the end of the season there was a more unpleasant episode. During a game at Milwaukee on September 3, Courtney (according to American Association president Bruce Dudley) spat twice on umpire John Fette and struck him with a bat. Courtney was ejected, fined $100, and suspended indefinitely.[22]

Nonetheless, the Yankees were able to call Clint up later that month. He made his big-league debut on September 29 at Yankee Stadium in the second game of a doubleheader against the Red Sox. He went 0 for 2 and was hit by a Mickey McDermott pitch.

Courtney did not lack confidence; he viewed himself as a legitimate contender for Yogi Berra’s job. Realistically, there was no opportunity for him in the Bronx. Berra was the 1951 AL Most Valuable Player; backup catchers Ralph Houk and Charlie Silvera saw little action while Yogi was in his prime.

Therefore, the Yankees traded Courtney to the St. Louis Browns on November 23, 1951. Rogers Hornsby, who had become the Browns’ manager, recommended that the club obtain Courtney. The Browns felt so confident in Courtney that four days later they traded away another fine catcher, Sherm Lollar. Although the door had opened in the majors, Clint still resented his lack of opportunity with the Yanks.

Near the end of spring training in 1952, the Browns’ new starting catcher got his “Scrap Iron” nickname. Teammate Duane Pillette and announcer Buddy Blattner have received credit for this label, which came about after a footrace against sportswriter Milton Richman in a railway yard near the end of spring training. Clint tumbled, sliced himself up all over on glass and rocks, but stayed in for the next day’s exhibition game when Hornsby threatened him with a fine. “Bandaged up like King Tut,” as his sister Jo put it, he could barely hold the bat but still got three hits against Early Wynn. According to Richman, Clint missed several weeks, but he was the Opening Day starter.[23]

His first big-league hit came in the fourth game of the season; it was a bases-loaded triple off Bill Kennedy of the White Sox. His first homer in the majors came on May 6 at Shibe Park off Philadelphia’s Bob Hooper. Although he missed a couple of weeks in June after a foul tip split a finger, Courtney played in 119 games and batted .286 with 5 homers and 50 RBIs. The Sporting News named him its AL Rookie of the Year (in the baseball writers’ voting, Athletics pitcher Harry Byrd got nine votes, Clint eight, and Sammy White seven).

When the owner Bill Veeck fired Hornsby in June 1952, outfielder Jim Rivera and Courtney were the only men who were sorry to see the Rajah go. Clint said, “He never spoke to me either but I understood him. Most of these fellows couldn’t play for him but I could. He was tough but he was okay with me.”[24] It was reported that the other Browns expressed their gratitude by giving owner Veeck a trophy, but there is lingering suspicion that Veeck bought the trophy himself as another of his publicity stunts.

About a month later, on July 12, Clint got into the first of his on-field fights with the Yankees and the noted sucker-punch specialist Billy Martin. Clint apparently spiked Billy in the second inning at Yankee Stadium.[25] Then, “with two out in the eighth, Courtney tried to steal second and was out by a wide margin as Martin applied a hard tag to Courtney’s face.” Clint followed Billy, who pivoted and slugged the catcher. A brawl ensued and umpire Bill Summers was knocked flat.[26]

Clint drew a three-game suspension and a $100 fine. As Milton Richman noted, “Courtney already had a reputation for belligerence when he first came up.” He described how the catcher “kayoed” and “flattened” two different teammates who were either not playing team ball or kibitzing card games in which Clint was losing.[27]

Courtney most likely got his other monicker, “The Toy Bulldog,” in 1952 as well. He credited Browns broadcaster Dizzy Dean, though the new manager Marty Marion adopted it as his pet name for the catcher. [28]

During that season Clint developed a rapport with Satchel Paige. Bill Veeck told the story in his autobiography, Veeck as in Wreck. Courtney “had served notice that he wouldn’t catch Satch. I liked Courtney because he was a rough, tough little man who played the game for all it was worth. I felt very strongly that this was a matter entirely of environment and upbringing. Once Clint got to know Satch, I was sure, he’d come around — even though I was perfectly aware that Satch would do nothing to appease him.”

That was how it worked out.[29] Veeck later said, “One day I noticed Clint was warming him up. [A week later] I walked into a bar in Detroit called The Flame. There were Leroy and Clint having dinner together. Courtney told me, ‘My pap’s comin’ up tomorrow from Lou’siana and he’s gonna be mighty mad when he hears about us being friends. But Satch and me figure we can whup him together.’”[30] Eventually Paige said, “There’s the meanest man I ever met, but I’m glad he’s on my side.”[31]

That summer, as a reward for learning to lay off high fastballs, Veeck gave Clint a white-faced Hereford calf for his ranch back in Coushatta.[32] This was the catcher’s main off-season occupation for many years. “I aim to own my own land ‘n’ all the cattle I can git,” he said in 1953.[33] He wound up with 200 good acres and rented up to 500 more at times. He also brought thoroughbred racehorses to Red River Parish and had a big greenhouse full of 10,000 tomato vines, eggplants, and peppers.

“Courtney was country to the core,” wrote Warren Corbett in his biography of Paul Richards. “He sometimes loaded his hunting dogs, and, allegedly, his smaller cows, into the backseat of his Cadillac, which was carpeted with empty beer cans. ‘I rode with Clint once,’ pitcher Dick Hall said. ‘It was like being in a barn.’”[34]

Part of the Courtney lore concerns how oblivious he was to pungent aromas. As he inspected cattle in the stockyards of Chicago and Kansas City, he would stomp around in manure and then head directly to the ballpark.[35] When Early Wynn and Les Moss smeared Clint and his mitt with Limburger cheese as a practical joke, he wasn’t fazed a bit; umpire Jim Honochick was the one revolted.[36] In fact, Charlie Metro remembered how Clint — “They called him a billy goat. . .I don’t think he ever took a shower” — used his own hunk of cheese inside his mitt as a shock absorber until even he found it too rank.[37]

In 1953 Courtney sought a 60 percent raise from $7,500 to $12,000 after his fine rookie year.[38] Bill Veeck responded with an $11,000 contract. Courtney wrote back, “Dear Veeck: I changed my mind. I want $14,000, not $12,000. Clint.”[39]

On April 28 Scrap Iron mixed it up with the Yankees again. In the 10th inning at Sportsman’s Park, he got riled. His old minor-league teammate Gil McDougald had jarred the ball loose on a play at the plate, which he always protected zealously. In response, he rammed into Phil Rizzuto at second base with spikes high in the bottom of the inning. The Yankees came to the defense of their little shortstop, and it turned into another free-for-all. Umpire John Stevens suffered a dislocated shoulder; fans heaved soda bottles on the field; action was halted for 17 minutes. AL President Will Harridge meted out a total of $850 in fines — including $250 on “instigator” Courtney for “violating all rules of sportsmanship.”

In retrospect, this brawl has been billed as a rematch between Courtney and Billy Martin. Newspaper accounts at the time, though, showed that Allie Reynolds got the first shot in at Clint, not Billy. Reynolds later said, “Clint Courtney? Did Billy get the credit for that one? Heck, I was the one who K.O.’d Courtney.”[40]

The ’53 season also featured another dustup in July. This time Clint squared off with Johnny Bucha of Detroit when the opposing catcher came in hard at the plate. Over the course of the year he produced much less with the bat, driving in just 19 men on four homers while hitting .251 in 106 games. Broken fingers early in the season hampered him.

In December 1953 Clint went back to Mexico, as the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis made him manager. On January 11, 1954, he married a St. Louis woman, Dorothy Knelange. The wedding took place in Ciudad Obregón.[41] The newlyweds must have postponed their honeymoon, though — two days after they exchanged vows, Clint appeared in the league’s All-Star game. They had five children: Wendell, Cynthia, Kathleen, Nancy, and Stephen.[42]

Scrap Iron was still first-string after the Browns franchise shifted to Baltimore for the 1954 season. His home run off Chicago’s Virgil Trucks on April 15 was the first in the big leagues at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. Clint hit a respectable .270 with 4 homers and 37 RBIs. Perhaps his most distinctive number at the plate, though, was his strikeout total: just seven in 437 plate appearances, which remains a club record. Throughout his big-league career, Courtney fanned only once for every 22 times he came to the plate (4.5 percent).

On November 17 of that year, the Orioles obtained catcher Gus Triandos (who had also been stuck behind Yogi Berra) in the 17-player deal with New York. A few weeks later, Clint became part of a seven-man swap with the White Sox. “We wanted catching strength,” said Marty Marion (by then Chicago’s manager), “and I think we got it. The Orioles were interested in pitching and in [Fred] Marsh.”[43]

At the end of March 1955 Clint told United Press, “Gone soft, hell! I’m just as wild as I ever was. I still don’t take nuthin’ from nobody. They say I turned into a lamb just because I got fined for one of those fights, huh? Well, whoever says it is crazy.” He added, “This is a good club to be with — providin’ they gimme some work to do.”[44]

Scraps spent less than half a season in Chicago. He didn’t get off on the right foot there, holding out for a better contract from Frank Lane (whom he addressed as “Dear Lane” in his negotiating letter).[45] On June 7, 1955, the White Sox sent him in a 3-for-1 deal to the Washington Senators. Courtney finished the year hitting .309 and he was at .300 in 1956. He was a semi-regular, getting roughly 300 plate appearances a year from 1955 through 1957. He split time with Lou Berberet (who had been in the Yankees system at the same time as Clint) and Ed FitzGerald. In ’57 Courtney suffered a broken hand on a foul tip, missing nearly all the month of May. Manager Charlie Dressen fined him $200 for “insubordination.”[46]

The Senators had a surplus of catchers in 1958 as Steve Korcheck returned from the Army. Courtney was the subject of trade talks in the early part of the season. Washington wound up trading Lou Berberet instead and Clint set a number of career highs: games played (134), plate appearances (515), home runs (8), and RBIs (62).

Courtney split the Senators’ catching duties almost evenly with Hal Naragon in 1959. He had a heart-attack scare in February, but the ailment was later diagnosed as pleurisy.[47] Then in the exhibition season, he suffered a hairline fracture of the leg in a collision at the plate with Hal Smith. Expected to be out for a month to six weeks, he was back in action mere days later. However, mumps kept him out of the lineup from late April through early June. His batting fell off to .233-2-18.

On April 3, 1960, Washington traded Scrap Iron back to Baltimore, along with Ron Samford, for Billy Gardner. “There was a lot of nose holding in Baltimore. Gardner had been one of the fans’ favorites and they didn’t think Courtney was the best the Orioles could get for him.” Gus Triandos had a sore thumb and went on the disabled list, though. As Clint drawled, “Ah got a hunch Ah’ll play more than a lot of people think. Ah can hit and Ah ain’t as bad a catcher as a lot of people think.” [48]

Orioles manager Paul Richards agreed. “You know, Courtney is about three times better a catcher than anyone has ever given him for being. He hops around out there, but he gets the job done. He’s one of the fellows who doesn’t mind winning.”[49] A word about Courtney’s arm is in order, too. He played in a time when the stolen base was largely out of vogue, but throughout his career, he nailed 41 percent of opposing runners (198 out of 478). In addition, he possessed another valuable skill as a receiver, being an expert “framer” of pitches.

What proved Clint’s prediction right in 1960 was Hoyt Wilhelm and his knuckleball. The butterfly had bedeviled Gus Triandos, who surrendered 28 passed balls and 29 wild pitches in 1959. “The more I caught him, the worse I got,” said Triandos in 1984.[50] During the early going in 1960, Gus and Baltimore’s other catcher, Joe Ginsberg, gave up 11 more passed balls and four wild pitches while Wilhelm was working. The O’s staff had another knuckleballer too, Hal “Skinny” Brown.

The innovative Richards, noting that there was no regulation governing the size of catcher’s mitts, came up with the model called “Big Bertha” or “the elephant ear.” He had first hatched the idea in the fall of 1959; in May 1960 he said, “with the situation no better, I sent [Orioles pitching coach] Harry Brecheen to Chicago to a factory.” The mitt was 42 inches in circumference and (even after eight ounces of padding was removed to make it less unwieldy) weighed 30 ounces, vs. the standard 33-34 inches and 27 ounces.[51]

Courtney got to break in the mitt on May 27 when Wilhelm pitched against the Yankees. The Orioles won 3-2, and the game was free of passed balls. After the game, Clint said the glove was easy to handle. “I don’t know how many pitches would have jumped past me with a regular glove. This was the first time I ever caught [Wilhelm]. Boy is he rough to catch. I don’t see how anybody ever hits him.”[52]

First baseman Jim Gentile said, “Clint was lower to the ground. Ol’ Scrap Iron, he’d get back there with that big glove on, and he’d just pounce on it.”[53] The costs as well as the benefits became visible on August 15. Again facing the Yankees, with Wilhelm on in relief, the Orioles were leading 3-2. After Héctor López walked, Courtney dropped a foul pop by his old teammate, Mickey Mantle. After the reprieve, Mickey then hit a game-winning two-run homer. (Major League Baseball’s rules committee enacted a rule against the Big Berthas in December 1964, establishing a maximum circumference of 38 inches for catcher’s mitts.[54])

The oddity of Courtney’s 1960 season was a bout with the yips. Various catchers (most notably Mackey Sasser) have found themselves unable to throw the ball back to the pitcher normally. Clint got around the mental block — which he may also have suffered at some point in the ’50s — either by throwing the ball to third base or by walking partway to the mound.[55] Fortunately, the malady did not last long, but it was ironic because Courtney had been known in the past for “burning” the ball back to his pitchers.

On January 24, 1961, Clint was packed off again, going to Kansas City in a 5-for-2 trade. Scraps appeared in just one game for the A’s, however, before they returned him to Baltimore on April 14. Courtney’s last major-league appearance came on June 24, 1961. On July 1, the Orioles sent him down to Triple-A Rochester, which needed a catcher. Paul Richards said, “You don’t have to go back to the minors if you don’t want to, but if you did you’d be doing the organization a big favor.”[56]

In February 1962 the expansion Houston Colt .45s signed Clint as a free agent. Richards, who had become the Colts’ general manager, kept the promise he had made the previous year: whatever club he was with, there would be a catching job for Courtney.[57] Bill Giles, later principal owner of the Phillies, was then Houston’s traveling secretary. Giles later said, “His [Clint’s] role was really to be Richards’ valet, catering to his every whim and carrying his golf clubs.”[58] Some of the many amusing Courtney anecdotes revolve around the golf course, with Scraps shagging balls for Richards on the driving range, getting one free throw per hole when he took the game up himself, and not being averse to improving his boss’s lie with a well-timed kick.[59]

Although the big club cut the 35-year-old veteran in April 1962, he played three games for AAA Oklahoma City but then stepped down to the Durham Bulls, a Class B team. Lou Fitzgerald, another of Paul Richards’ men, had asked Richards if he could have an experienced catcher to help develop his young pitching prospects. At Durham, Clint worked in particular with Wally Wolf, who would eventually pitch in six games for the California Angels in 1969 and 1970.[60]

Clint hung on in the minors for two more years as a player-coach. He got into 61 games in 1963 at Durham (which had become Class A) and San Antonio (AA). A 1997 retrospective in the San Antonio Express-News carried the headline, “Veteran backup catcher was heart of S.A. team,” with the subhead, “Courtney’s hard-working, simple style had an effect.”[61] He passed on his experience to two future big-league receivers, Dave Adlesh and Jerry Grote. Grote in particular was in the same mold as Scraps, a tough take-charge guy.

Clint finished up behind the plate with 37 games for San Antonio in 1964. In November he rejoined Houston as a combination bullpen coach and catcher. His feisty side was still on display in the ’65 season, as he got into a brief fistfight with teammate Lee Maye. As Courtney was hitting fungoes, a little kidding got out of hand. Clint got a bruise on his head and a minor finger injury.[62]

After that season ended, Paul Richards lost his job in Houston, and so did several of his coaches, including Clint. Yet as Richards moved on to Atlanta as farm director, he found a spot for Courtney as a roving minor-league catching instructor. Clint also joined the Braves for spring training 1967, where the catching drills were so rigorous that Gene Oliver nicknamed the camp “Stalag 17.” Joe Torre adjusted — Scraps said, “Joe is coming along pretty good; he’s not even complaining any more.”[63] But the aching Oliver moaned, “When I dream, all I can see are a bunch of baseballs coming at me and a voice yelling, ‘Git out ’are and git a-holt uv of that ball.’”[64]

Richards cited Courtney’s influence in persuading him to draft Ralph “The Roadrunner” Garr out of Louisiana’s Grambling University in 1967, although another Louisianian, Mel Didier, is the scout of record. In the summer of ’67 with the Austin Braves, Courtney drove Garr and the 26th round pick, Dusty Baker, to Texas League games in his pickup. Whoever had the most hits the night before got to sit up front — a real incentive, given the likely state of the truck bed. [65]

Courtney remained as an instructor through early 1970. He then became a manager in U.S. baseball for the first time, and he got to do it close to home in Louisiana. Clint took over the AA Shreveport Braves in early May after the team got off to a poor start under his good friend Lou Fitzgerald. It was originally supposed to be a temporary assignment that allowed him to visit his father and brother-in-law, who had both been ill, but it lasted for the rest of the season.[66] Jo Lawson recalled, “That was my husband, Bobby. He and Daddy were already better and they all went fishing and quail hunting together, with the dogs. It sure was nice that Clint could come home at night.”

In 1971 Courtney was reassigned to the Greenwood, South Carolina, Braves of the Class A Western Carolina League. He led them to a league-best 85-38 record. Jim Joyce of the Greenwood Index-Journal wrote, “Clint ‘Scraps’ Courtney is a man who means what he says and doesn’t beat around the bush getting the job done.”

The following season Clint stepped up to Savannah, the Braves’ Class AA affiliate in the Southern League. He stayed with the organization even after Paul Richards was pushed out in January 1973. Scrap Iron advanced to Atlanta’s top farm club, Richmond, that June. He replaced Bobby Hofman, who gave up the job under doctor’s orders because of high blood pressure. The man who took over at Savannah was Hank Aaron’s younger brother Tommie. At the time, it was the highest level a black manager had reached in organized baseball.

As a manager, Courtney would never ask a player to do anything he could not do. He stressed the importance of working together and getting along with each other. Echoing his own experience, he took up the cause of underdogs. One example was a little pitcher from the Bahamas named Wenty Ford. Ford was a junkballer who was stuck in the Braves chain, but Scraps loved his craft and guile. Wenty pitched the best ball of his career at Richmond in ’73 and got his cup of coffee in the majors that September.

In July 1974 Atlanta fired Eddie Mathews as manager. The Braves narrowed their choices for successor down to two: Clint and Clyde King. (Hank Aaron was miffed that neither he nor Tommie was considered.) Courtney wanted the job badly. Milton Richman asked him, “Do you want to manage in the big leagues that much?” Clint responded, “Does a goat have horns?” He also credited Richards and the new Braves GM, Eddie Robinson, for teaching him “little things, inside baseball. . .how to win.”[67]

Atlanta hired King and Courtney stayed at Richmond. The team came in second in the Southern Division of the International League in 1974 after a last-place finish the previous year. Charleston Gazette sports editor A.L. “Shorty” Hardman wrote, “If the Braves are improved, credit it to ‘Scrap Iron’ — there’s one thing you can always be sure of, he’ll let you know where you stand with him.”

On Sunday, June 15, 1975, Richmond arrived in Rochester for a series. That night Scraps was playing table tennis and talking baseball with several of his players at the team hotel, the Colony East Motor Inn. Team trainer Sam Ayoub said, “Courtney had played just one game of Ping Pong and he decided to rest for a while.” Courtney began talking with player Al Gallagher and “then he just keeled over and hit the floor,” Ayoub said. Stricken by a heart attack, Clint was pronounced dead on arrival at Genesee Hospital early on Monday morning. He was 48.[68]

Although Clint chewed tobacco, he was not a smoker, and he did not have a history of heart trouble. Jo Lawson said, “I am a nurse, and I remember that a few years before he came in short of breath with chest pains. But he was checked out and there were no signs of a problem.”

Courtney was buried in Mount Zion Cemetery in Hall Summit. Though neither of them is on his gravestone, two fitting epitaphs came from men who played for and with Scrap Iron. Clint’s friend with the Senators, pitcher and self-styled Cuban cowboy Pedro Ramos, said, “Clint Courtney. . .was a funny guy who’d drink a lot of beer and talk about cows.”[69] Jeff Geach, a minor-league utilityman at Greenwood, Savannah, and Richmond, said, “On the field he gave you hell. . .off the field he treated you like one of the family.”

Grateful acknowledgment to Jo Lawson for input from her own biographical sketch, clippings, and personal memories (April 2010). Thanks also to SABR member Warren Corbett.

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano. Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998.

Sortillón Valenzuela, Manuel de Jesús. Temporadas de la Liga del Béisbol de la Costa del Pacífico, www.historiadehermosillo.com/BASEBALL/Menuff.htm

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

[1] Addie, Bob. “Senators’ Rugged Individualist.” Baseball Digest, May 1959: 81.

[2] Daniel, John. Rogue River Journal: A Winter Alone. Washington, DC: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2005: 23. For similar sentiments, see also Cole, Diane. “Old Scrap Iron.” Psychology Today, May 1988 (condensed in Reader’s Digest, August 1990).

[3] Wolff, Miles. “Diary of a Minor League Season.” Anthologized in Baseball in the Carolinas: 25 Essays on the States’ Hardball Heritage (Chris Holiday, editor). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002: 139.

[4] Richman, Milton. “‘Tough – compassionate’: Clint Courtney dead at 48.” United Press International, June 17, 1975.

[5] Broeg, Bob. “Baseball’s Noisiest Newcomer,” Saturday Evening Post, April 25, 1953.

[6] Condon, David. “Clint Courtney: Baseball’s No. 1 Battler!” Chicago Tribune, March 7, 1955: L24; Baseball Digest, June 1955; 63.

[7] Anderson, Norris. “Sports Today.” Miami News, August 17, 1958.

[8] McMaster, L.A. “Specs Keep Clint Courtney Behind Bat.” The Sporting News, May 21, 1952: 4.

[9] Condon, op. cit.

[10] One example was Burton Bruckman, a catcher at Purdue and then in the Cardinals chain in the early 1930s. Another was Gene Lillard in the Pacific Coast League in the 1940s.

[11] Broeg, Bob. “Scrappy Clint Take-Charge Guy With Mitt.” The Sporting News. September 24, 1952: 4.

[12] Anderson, Norris. “Sports Today.” Miami News, June 11, 1958: 3D.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Metro, Charlie and Thomas L. Altherr. Safe by a Mile. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2002: 136.

[15] Broeg, op. cit.

[16] Spink, C.C. Johnson. “Lead-Off Men on Writers’ AL Lists.” The Sporting News, January 6, 1954: 2.

[17] Allen, Maury. Damn Yankee; The Billy Martin Story. New York, NY: Times Books, 1980: 77. Billy blended another spiking from 1946 into bitter memories of his foe. This one involved a third baseman named Eddie Lemade (who was later killed in action in the Korean War), but Courtney had not even turned pro yet. Allen, op. cit.: 32; Martin, Billy and Peter Golenbock. Number 1. New York, NY: Dell Publishing, 1981: 172-73.

[18] Metro, op. cit.: 136.

[19] Condon, op. cit.

[20] Llorens, Santiago. “Yankee Rookie Tops Star Poll in Puerto Rico.” The Sporting News, January 3, 1951: 25.

[21] Milwaukee Journal, June 26, 1951: 7.

[22] “Clint Courtney of Blues Suspended and Fined.” Associated Press, September 6, 1951.

[23] Richman, op. cit.; The Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965.

[24] “Only Rivera, Courtney Sorry Hornsby Gone.” Associated Press, June 12, 1952.

[25] Effrat, Louis. “Raschi Pitches One-Hitter as Yankees Crush Tigers in Two Games.” New York Times, July 14, 1952: 21.

[26] “Tagged Too Hard, Courtney Swings Fists at Martin.” Associated Press, June 13, 1952.

[27] Richman, op. cit.

[28] The Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965.

[29] Veeck, Bill. Veeck — as in Wreck. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962:190.

[30] Boswell, Thomas. “Satchel Paige: ‘Best I Ever Saw – Veeck.” Washington Post, June 9, 1982.

[31] Broeg, “Baseball’s Noisiest Newcomer.”

[32] Broeg, “Scrappy Clint Take-Charge Guy With Mitt”

[33] Broeg, “Baseball’s Noisiest Newcomer.”

[34] Corbett, Warren, The Wizard of Waxahachie. Dallas, Texas, Southern Methodist University Press, 2009: 225; Klingaman, Mike. “In nest of zanies, 3 stood out.” Baltimore Sun, August 31, 2004: 1E.

[35] Klingaman, op. cit.

[36] Story originally told by Al Lopez and often cited. First appearance may have been Stann, Francis. “Scent-sational catcher.” Baseball Digest, May 1960: 86.

[37] Metro, op. cit.: 121-123.

[38] “Courtney Asks $12,000; Spurns Browns Offer.” Chicago Tribune, January 17, 1953: A3.

[39] Condon, op. cit.

[40] Tullis, John. I’d Rather Be a Yankee. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1986: 229.

[41] “Clint Courtney Weds.” Associated Press, January 19, 1954.

[42] Duvall, Bob. “Whatever Became of. . .?” Baseball Digest, May 1970: 47.

[43] “Braves Seek Pirates’ Thomas; White Sox get Clint Courtney.” Associated Press, December 6, 1954.

[44] “Who’s Getting Soft? Not Clint Courtney.” United Press, March 29, 1955.

[45] Prell, Edward. “Courtney and Keegan Cool to Sox ’55 Terms.” Chicago Tribune, January 22, 1955: B3.

[46] “Dressen Reveals Clint Courtney Tapped For $200.” United Press International, May 5, 1957.

[47] “Courtney Released After Hospital Tests.” Associated Press, February 5, 1959.

[48] “Clint Courtney Big Help in Oriole Drive.” Associated Press, June 3, 1960.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Hertzel, Bob. “There Is Nothing Quite Like a Baseball Glove.” Baseball Digest, September 1984: 30.

[51] “Giant Glove Helps.” Milwaukee Journal, May 28, 1960: 7.

[52] “Catcher’s Mitt Helps Orioles Win.” Associated Press, May 28, 1960.

[53] Eisenberg, John. From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: An Oral History of the Baltimore Orioles. New York, NY: Contemporary Books, 2001: 101.

[54] Maher, Charles. “No More Giant Mitts To Be Seen.” Associated Press, December 2, 1964.

[55] Klingaman, op. cit.

[56] Richman, Milton. “Richards Keeps Promise, Hires Courtney to Catch for Houston.” United Press International, February 13, 1962.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Giles, Bill with Doug Myers. Pouring Six Beers at a Time and Other Stories from a Lifetime in Baseball. Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books, 2007: 45.

[59] Corbett, op. cit., loc. cit.; Eddie Robinson, interview by Warren Corbett, August 18, 2006, Fort Worth, Texas; Herskowitz, Mickey. “The Foremost Salvage Master.” Baseball Digest, June 1963: 30.

[60] Horner, Jack, “Scrap Iron Turns Out to Be Gold Mine as Talent Tutor.” The Sporting News, June 2, 1962: 31.

[61] King, David. “Veteran backup catcher was heart of S.A. team.” San Antonio Express-News, August 24, 1997: 15C.

[62] “Astros Need Fighters; Maye, Coach Oblige.” Associated Press, July 29, 1965.

[63] “Torre Stops Complaining.” Associated Press, March 1, 1967.

[64] “Brave Receivers Have Nightmares.” Gadsden (Florida) Times, March 5, 1967: 27.

[65] Buchholz, Brad. “Disch days.” Austin American-Statesman, July 9, 2000: A1.

[66] “Courtney Is Temporary Skipper at Shreveport.” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970: 40.

[67] Richman, Milton. “Courtney Anxious to Tackle Braves Job.” United Press International, July 23, 1974.

[68] “Clint Courtney Collapses, Dies.” Associated Press, June 16, 1975.

[69] Peary, Danny. We Played the Game. New York, NY: Hyperion, 1994.

Full Name

Clinton Dawson Courtney

Born

March 16, 1927 at Hall Summit, LA (USA)

Died

June 16, 1975 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.