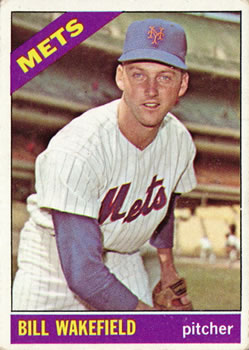

Bill Wakefield

In the one (and only) year that Bill Wakefield pitched in the major leagues, 1964, he set a Mets team record for game appearances that would stand up for 13 more years, and packed into a single season a full-length career’s worth of excitement and highlights, ending with a nail-biting season-ending game that decided the National League pennant.

In the one (and only) year that Bill Wakefield pitched in the major leagues, 1964, he set a Mets team record for game appearances that would stand up for 13 more years, and packed into a single season a full-length career’s worth of excitement and highlights, ending with a nail-biting season-ending game that decided the National League pennant.

The early Mets, of course, were never themselves within sniffing distance of the National League pennant, but Wakefield’s final game, in which he surrendered the winning runs to the eventual world-champion St. Louis Cardinals, was pivotal on the most dramatic final day in regular-season National League history. Wakefield’s key part in the pressurized game was doubly meaningful to him because he had been traded to the Mets before the season from the Cardinals, who had signed Wakefield to a large bonus contract. Furthermore, Wakefield knew many of his Cardinal opponents very well both professionally and personally.

Wakefield was only 23 years old for most of that 1964 season, having been born on May 24, 1941, (the same day as Bob Dylan) in Kansas City, Missouri. He was the only child of Dr. Franklin Horton Wakefield, a surgeon and general practitioner, and Roberta Jones Wakefield, known as Bobbie, a nurse who had met Dr. Wakefield while working in Research Hospital, where their son would be born years later.1

Dr. Wakefield had studied medicine with the prominent plastic surgeon Dr. Sumner Koch (from whom William Sumner Wakefield’s middle name derives) at Northwestern’s medical school; he had earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Missouri and had graduated from Central High School in Kansas City only a few years after Casey Stengel, his son’s eventual big-league manager, had attended Central High.

Bill Wakefield enjoyed a comfortable middle-class upbringing, interrupted in 1943, when Dr. Wakefield joined the U.S. Army, despite being a 43-year-old married father, serving in the Army Medical Corps overseas throughout the Second World War.

After his father’s return, Wakefield attended grade school in Missouri, and moved just across the Kansas state line to attend the Pembroke-Country Day School, where he played shortstop on that high school’s baseball team and eventually pitched. He also played high school football (a punter, he averaged 44 yards per kick) and basketball, where he played guard, making the all-district team in his senior year.

One of his high school’s fiercest rivals, Bishop Ward High, the top-ranked basketball team in Kansas, featured the future Cardinals star pitcher Ray Sadecki, a few months older than Wakefield and a year ahead of him in school. The two future big-league pitchers guarded each other on the hardwood, and pitched against each other on the diamond. Wakefield’s team beat Sadecki’s in a January 1958 basketball game, and Sadecki personally led his baseball team to victory, pitching a 1-0 shutout, and smashing a home run off of Wakefield to score the game’s sole run.

Dr. Wakefield worked long hours at the hospital, often working a six- or even seven-day week, taking Thursday afternoons off to golf with his son, and with occasional bowling outings and the annual Missouri-Kansas football game. Mrs. Wakefield oversaw most of young Bill’s early athletic competitions. From his earliest days, Wakefield rooted for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League, and the Kansas City Blues, the Yankees’ top farm team, until the Athletics relocated to KC from Philadelphia. He attended the first Athletics’ home opener in April 1955.

In 1958, he was offered a job as an office boy for the Athletics by Joe Bowman, a former National League pitcher and Wakefield’s neighbor, who was also head of scouting for the team.

Wakefield soon learned that the best parts of the job included driving around town in the club’s Jeep delivering tickets to sales outlets, picking up box lunches for the players at Arthur Bryant’s barbeque restaurant, and helping legendary groundskeeper George Toma and his crew prepare the field and the tarp before games. His predecessor as the A’s office boy had been his old school pal and rival Ray Sadecki, who had signed a $50,000 bonus contract with the Cardinals in 1958. Wakefield’s own bonus contract, even larger, was just around the corner.

During the summers of 1959 and 1960, Wakefield pitched in the amateur Ban Johnson League in Kansas City, hurling back-to-back no-hitters in his second year. Wakefield’s performance drew 10 big-league clubs’ scouts to his house in Leawood, Kansas, throughout the summer of 1960.

The two top offers came from the Baltimore Orioles and the Cardinals, each offering a $60,000 bonus. The Cardinals’ advantage was more than monetary—they welcomed the Wakefield family to their stadium, where they sat with club owner Gussie Busch in his box seats. They also had Wakefield’s former high school rival Ray Sadecki telephone the young pitcher, advising him to sign with the Cardinals.

Furthermore, the Cardinals agreed, as Bobbie Wakefield had insisted, to letting her son attend college for two quarters of each off-season. Wakefield had entered Stanford University in September of 1959, majoring in geography, with an emphasis in geology and economics. After protracted negotiations, in early August of 1960 he signed with the Cardinals.

Instead of pitching for a minor league team for the remaining few weeks of the 1960 season, he travelled again to St. Louis, where he worked out with the Cardinals during a home stand against the Giants and the Dodgers, pitched some batting practice, and lived in the Chase Hotel with players Ernie Broglio, Bob Grim, Tim McCarver, and Carl Sawatski. He got advice from coaches Harry Walker (“Get yourself some shower shoes”) and Howie Pollet (“Don’t throw too many BP pitches without a screen in front of you”) and the greatest Cardinal of all, Stan Musial, threw an arm around Wakefield, making him feel like a teammate.

Wakefield received pitching and attitude advice from Bob Gibson, and went out with McCarver to movies and dinners in Gaslight Square. He witnessed Ray Sadecki losing to the Giants on a Wednesday night, and overheard Gibson, not yet in the starting rotation, consoling Sadecki, “Hang in there, Ray, there’ll be good days and bad days,” which would be true for both of them.

A few games later Wakefield and Broglio had dinner, and then Wakefield watched Broglio outduel Sandy Koufax in a 2-0 win. In the locker room after the shutout, Broglio met Wakefield’s eye and said, “Good dinner last night.”

In September, Wakefield started his sophomore year at Stanford. He never played varsity sports in college, despite having received an athletic scholarship from Stanford. Freshmen in 1959-60 were prohibited from playing varsity sports, but in an intramural basketball game his freshman year, Wakefield broke his right wrist going for a lay-up and missed the freshman baseball season as a result.

He joined the Delta Tau Delta fraternity at Stanford with future Mets teammate Darrell Sutherland (friend and future Cy Young Award winner Jim Lonborg was in Phi Delt at Stanford at the same time) but he became ineligible for college athletics when he signed his Cardinals’ contract. Stanford allowed him temporary leaves of absence during the spring and summer quarters from 1961 through 1966 while the Cardinals (and later, the Mets) required Wakefield’s services.

Wakefield joined the Lancaster Red Roses of the Eastern League in the spring of 1961, moving up the next season to the Tulsa Oilers, where 1940s Cardinal star Whitey Kurowski managed the team into the Texas League playoffs. Among Wakefield’s Oiler teammates were future Cardinals stars Dick Hughes and Dal Maxvill, who in 1964 would be the final batter Wakefield faced in the big leagues.

In mid-1963, Wakefield joined the Cardinals’ top AAA farm team, the Atlanta Crackers, managed by Harry “The Hat” Walker. There Wakefield won back-to-back games in relief in the International League playoffs that September. But on November 17, 1963, Wakefield learned that he had been traded, along with outfielder George Altman, to the New York Mets for veteran pitcher Roger Craig.

No longer competing with the likes of Bob Gibson, Curt Simmons, Ray Sadecki and other star pitchers for a place on the Cardinals’ staff, he was pleased to find himself now competing among the more modest pitching talent on the early Mets.

“I had friends from Stanford,” Wakefield recalls, “fellows from New York, who called me up when they heard about the trade and told me this would be the chance of a lifetime — the way the Mets are playing now, they told me, you could be starting for them this year. And they were right.”2

Wakefield remembers that first spring training. “I arrived in Florida on March 7th,” he says, “which was kind of late to be reporting to camp, but I pitched well my first few times out. One spring training game, I remember, was against the White Sox, and Casey [Stengel, the Mets’ manager] was yelling over to his friends in the White Sox dugout, like Al Lopez, about how well I was throwing, and then I threw some more good games and I came north with the team. I asked Casey why the Mets had traded for me, and he said that he had friends back in Kansas City — where I’m from, and where he’s from, that’s how he got the name ‘Casey’ — who spoke well of me. It was surprising how much he knew about me. He knew my father was a doctor, and he told me that he had gone to dental school when he was young. Casey’s friends followed my career, and when he had the chance to pick me up, he did.”

“I had a good spring,” Wakefield said, “and also Carl Willey, who was the Mets’ best pitcher at the time, got hurt badly in a spring training game against Detroit. Gates Brown hit a line drive to the mound that broke Willey’s jaw. It was an awful sight — Willey never pitched effectively in the major leagues again. And that kind of opened up a spot for me. I played with Carl in the minors the following year in Buffalo. He was from Cherryfield, Maine. Worked in a clothing store in the offseason. That was a different time.”

Major-league players may have been more aggressive in 1964 — certainly, Ron Hunt, the Mets’ first elected All-Star that year, struck Wakefield as highly competitive. “Ron was a kind of, well, arrogant type of guy,” Wakefield recalls. “He invited pitchers to throw at him. If you’re going to crowd the plate, you’re going to get hit by a lot of pitches, but Ron didn’t care if other players liked him so much.”

“I did hit a number of batters that year, but that wasn’t deliberate. It wasn’t part of my style, or my intention, but I did hit [nine] batters just by throwing inside a lot,” Wakefield notes. He ranked fifth in the NL in “batters hit by pitches” in 1964, which was very high considering the number of renowned head-hunters in the league who pitched twice or more Wakefield’s 120 innings. “One game, I hit Jeff Torborg with a fastball right after I’d balked and people thought I hit Torborg because I was frustrated, but I just liked to jam guys on the first pitch.”

Wakefield didn’t mention that between his balk and the inside fastball to Torborg, his manager had protested the balk vigorously to Shag Crawford’s umpiring crew, while 40,000 fans at Shea Stadium were roaring.

Stengel had brought along many star pitchers in his long managerial career. Wakefield was the final young pitcher he nurtured to big-league success, though Stengel’s use of his pitching staff might strike a current fan as anything but nurturing.

“Pitchers didn’t really have specific roles back then, not like they do today. You weren’t a starter or a reliever, you just played when the manager put you in the game,” Wakefield says. “I wasn’t about to beg off of any assignment I got — I started, I relieved, sometimes in both ends of a doubleheader. I got the chance to get into a lot of games.” Wakefield appeared in 62 ball games in 1964, setting a club record that would stand until 1977. “No, I don’t follow baseball all that closely, but that was one record I kept track of.”

A modern pitcher who set a club record for appearances, of course, wouldn’t start any games at all, but Wakefield got several starting assignments in 1964, including the first night game at Shea Stadium on May 6, 1964, when he lasted into the fifth inning against the Cincinnati Reds. As a starting pitcher, Wakefield had not had a successful year: in his four starts, Wakefield averaged fewer than four innings, losing three of his starts, winning none of them, and posting an astronomical 9.82 ERA.

But Wakefield’s 58 appearances in relief were as brilliant as his starting stats were grim: he threw 105 innings of relief, in itself a huge workload by modern standards, with a 3-2 record. Most impressively, in his relief appearances his ERA was a sparkling 2.74. He was clearly the Mets’ best reliever, and by any standard was one of the very few bright spots on the Mets’ pitching staff of the 1964 season.

“When I was starting, I relied mainly on my four-seam fastball. I probably threw in the low 90s then, maybe 93 miles per hour. But when I was relieving,” Wakefield says, “my main pitch was the two-seamer, the sinker, because I’d come into games with runners on base, and it was important that I get the batters to hit into double-plays. In the Mayor’s Trophy game that year, I got Yogi Berra — he was the Yankees’ manager, but he played in the Mayor’s Trophy game — I got him to hit into a double play. I remember this tremendous roar when he came into the game; the fans were surprised to see him batting, I suppose.”

By the next season, Berra would join the Mets, as would veteran pitcher Warren Spahn, but during that 1964 season, Wakefield got to play alongside such veterans as Frank Lary, Tom Sturdivant, Frank Thomas, and Roy McMillan, all of whom Wakefield remembered as being helpful to a rookie.

“McMillan couldn’t really throw very well any more, but he was a very good shortstop. I liked Frank Thomas, he was very fair to me. Players joked with him, called him ‘Big Donkey’ and all that, but Thomas was a good guy. Sturdivant and Lary were willing to share ideas about pitching — but the guys I was competing against directly, the younger players, weren’t interested in helping me succeed. And I wasn’t trying very hard to help them, either,” Wakefield recalls, with amusement.

“Some of the younger players I liked a lot. Larry Bearnarth, who had gone to St. John’s — later became the Expos’ pitching coach, died very young — was a good guy, and a good coach. A lot of the pitchers on that club went on to become pitching coaches: Craig Anderson went to coach at Lehigh College, though Craig wasn’t so much interested in the mechanics of pitching back then. I still keep in touch with him. Galen Cisco had a long career as a pitching coach in the major leagues. Al Jackson, too,” Wakefield recalls.

“Mel Harder was our pitching coach in 1964,” Wakefield says, “and his advice was mostly that we should throw the curveball more. Of course, Mel threw a great curveball when he was pitching, but for those of us without a terrific curve, that maybe wasn’t such good advice. Spahn joined the club as a pitching coach, and an active pitcher, in ’65, and gave very simple advice: don’t throw the ball down the middle of the plate, he said. And also, because he never liked to run, he told us not to bother running a whole lot. But as far as the mechanics of pitching, Spahn just told us what worked for him. He’d hurt his right [non-pitching] arm as a young man, so he kept his right shoulder in towards his body as he pitched, but he didn’t tell us that we should pitch the same way as he did — that was just what worked for him, he said.”

Wakefield appeared in many historic games that 1964 season: the 33-inning Memorial Day doubleheader against the Giants, Jim Bunning’s Father’s Day perfect game, and the pennant-deciding final game against the Cardinals. “I faced one batter in Bunning’s perfect game and I got him out — Bunning faced 27 men and got them all out. The last batter was John Stephenson. Casey told Stephenson to get up there in the bottom of the ninth, and Stephenson said something like ‘I think I might strike out,’ and that’s exactly what Stephenson did,” Wakefield says.

In the final game of the season, and of Wakefield’s big-league career, the Mets were trying to defeat the Cardinals, who were in a very tight struggle for the pennant. The Mets had won the first two games of the series, and if they won the finale, there could be a three-way tie for the 1964 pennant between the Cardinals, Phillies, and the Reds, the last two of whom were playing each other in Cincinnati while the Cards faced the Mets in St. Louis. Wakefield remembers the Cardinal fans “were right on top of us, yelling, screaming the whole game. I gave up one hit, to [light-hitting reserve infielder] Dal Maxvill, it must have bounced 25 times before it got through the infield …”

Today, it is unimaginable that a rookie of Wakefield’s caliber would never pitch another major-league inning again, and that final loss in many ways exemplifies the strangeness of his subsequent demotion to the minor leagues.

He entered the game in the fifth inning with the score tied. “I faced four batters,” Wakefield says of his final appearance, “and I got two ground balls, an intentional walk, and a strikeout, but Maxie’s groundball made it through the infield.” Wakefield allowed two inherited runners to score, giving the Cardinals a lead they never lost, and they clinched the pennant when the Phillies beat Cincinnati.

Wakefield’s major-league career was over. He didn’t pitch poorly in his next spring training, and he didn’t get injured either. He threw only a handful of innings that spring, as the Mets had acquired some veteran pitchers over the 1964-65 winter such as Spahn, and had reacquired Wakefield’s 1964 teammate Frank Lary. The Mets also gained Pittsburgh pitching prospect Tom Parsons and Phillie prospect Gary Kroll, both competing for starting roles on the Mets, as well as former Met ace Carlton Willey, who was trying to regain his spot on the Mets staff.

To make competition fiercer, the Mets were required by the bonus rule then in effect to bring rookies Jim Bethke, Tug McGraw, and Kevin Collins north. During batting practice at Huggins Field in St. Petersburg, Mets’ General Manager Johnny Murphy called Wakefield over to tell him that they were sending him to Buffalo.

Casey Stengel, standing at Murphy’s side, said, “Apparently, I think you are a better pitcher than some of the other people around here.” Many other Mets’ coaches and teammates were surprised and dismayed that Wakefield hadn’t made the Mets roster, including Wes Westrum, who would become the team’s manager later that summer, and fellow Mets pitcher Jack Fisher, who suggested that Wakefield might want to play baseball in Japan.

Instead, Wakefield pitched for the Bisons until July 4, but spent the rest of 1965 pitching for the Chicago Cubs AAA affiliate in Salt Lake City. For his final professional season in 1966, he pitched for the Mets’ AA team at Williamsport, Pennsylvania, alongside such future Mets starters as Ken Boswell and Duffy Dyer, and future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan.

Wakefield was offered a promotion in mid-1966 to the Mets’ AAA team at Jacksonville, Florida, by Mets’ Minor League Director Bob Scheffing, but the pitcher liked his house in Williamsport, enjoyed playing for manager Bill Virdon, and declined the promotion. By that point, Wakefield understood that 1966 was probably going to be his final year in professional baseball.

In December 1964, Wakefield had married Karen Nelson, a classmate at Stanford. He and Karen would have two daughters, Monica and Amy, and divorce in 1976.

He graduated from Stanford on a delayed schedule, entering the University’s Class of 1963, but graduating in the Class of 1966. Wakefield took his final college exam during spring training of 1966, proctored by the St. Petersburg library’s staff, first asking Casey Stengel for permission to take the afternoon off baseball. (Retired by then, Stengel was still consulting with the Mets during spring training.) “Casey told me ‘Sure. Edna [Mrs. Stengel] always liked Stanford,’” Wakefield recalled.

Wakefield had been discussing starting a food distribution business with his father-in-law in the San Francisco area, and after the 1966 season the two men did just that in Richmond, California. His business, a factory producing Mexican foods, lasted until 1975, when it was sold to S&W Foods.

Wakefield went on to work as an off-shore buyer for Mattel, Inc., a multi-national toy manufacturing company that produced hula hoops, Slip ‘n’ Slide, Barbie dolls, and Frisbees among its products, travelling 75 times to the Far East for them until the mid-1990s, when he took a position as the pitching coach at Camp Sho-Me in Missouri with his former Williamsport manager Bill Virdon, Hall of Famers Gaylord Perry and Brooks Robinson, and other MLB players.

He married Joan Senz in 1987 and had two more children with her, a son, Edward in 1988, and a daughter, Laura in 1990, causing his former Mets teammate Rod Kanehl to send him a trivia question: Which former Met has fathered children in each of the past four decades? His second marriage lasted until 2001, and Wakefield retired in 2006 at the age of 65. He now lives in San Rafael, California.3

He married Joan Senz in 1987 and had two more children with her, a son, Edward in 1988, and a daughter, Laura in 1990, causing his former Mets teammate Rod Kanehl to send him a trivia question: Which former Met has fathered children in each of the past four decades? His second marriage lasted until 2001, and Wakefield retired in 2006 at the age of 65. He now lives in San Rafael, California.3

He very genially regards his major league career with pleasure and enthusiasm, not seeming to regret its brevity or to dwell on what could have been. He discusses his teammates, his coaches, and his managers with warmth, and keeps in contact with former teammates like George Altman, Craig Anderson, and, until his death in 2004, “Hot Rod” Kanehl, who had been “a kind of mentor” to Wakefield on the 1964 Mets.

After the last game of the 1964 season, which was also Kanehl’s (and Altman’s) last day as a Met, still wearing their Mets uniforms, Kanehl suggested to Wakefield that they congratulate the new NL champion Cardinals, so they walked into the raucous Cardinal clubhouse and shook hands with former teammates and opponents celebrating their success. Although Wakefield expected to be back in the big leagues, he knew that Kanehl had already decided to retire from the game, and remembers with satisfaction Kanehl getting a ninth inning pinch-hit RBI and standing on first base, knowing that would be his last appearance in the majors.

Other memories of his 1964 season are off-the-field memories: living in a Times Square hotel with teammates like Frank Thomas and Jesse Gonder, taking the No. 7 train from midtown Manhattan out to the brand-new Shea Stadium, and visiting the 1964-65 World’s Fair across Roosevelt Avenue from Shea. During that year’s All-Star break, where every Met except for All-Star second-baseman Ron Hunt (and manager Casey Stengel) got a few days away from Shea (where the All-Star game was played), Wakefield golfed with his fiancé’s father at Pebble Beach in California. “That was a beautiful vacation,” he remembers, with a broad smile.

He also has fond memories of coaches and managers who helped him, starting with Casey Stengel and Wes Westrum, each of whom took a special shine to the young Wakefield. The youngest coach on Stengel’s staff in 1964, Westrum — a veteran catcher and star with the 1951 and 1954 New York Giants — in particular advised him on the small edges he might use in game situations, such as how to keep runners close by throwing more efficiently to first base. Westrum also passed along opponents’ signs that he was gifted at picking up.

Another of the better coaches Wakefield recalls was former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Clyde King, who was a roving pitching instructor in 1963 for the Cardinals’ organization. The Atlanta Crackers’ pitching coach in 1963, ex-Yankee Johnny Kucks, merely advised him to throw his sinking fastball more, and other pitching coaches had given even more general advice (“throw strikes — but nothing down the middle of the plate”) but “Clyde was a confidence builder,” Wakefield recalls. “He made you believe you could throw any pitch at any time. I liked him a lot. Every time Clyde showed up, I pitched a terrific game. Coincidence? Or what I needed?”

One coach, hired by the Mets in spring training of 1965, was former Olympic star Jesse Owens, to whom Wakefield paid special attention, just for the thrill of being instructed in techniques of running by a world-class sprinter. He also got to meet one of his boyhood heroes, Satchel Paige, at a Cardinals’ minor league camp in 1961, when he introduced himself to Paige while shagging flies before a Portland Beavers game, a much bigger thrill for the 19-year-old from Kansas City than it was for the 55-year-old former Kansas City Monarchs star. Bill Wakefield got to meet, and play with, and against, and for all sorts of major stars and managers and celebrities in his brief major league career, savoring, as much as any 23-year-old could, earning his living playing the game he loved.

Last revised: August 25, 2017

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Steven Goldleaf (writing as Bret Sabermetric), “On 45 Years’ Rest,” The Cranepool Forum, July 11, 2009. http://archives.thecranepool.net/12000/f1_t12040.shtml

Maury Allen, Now, Wait a Minute, Casey! New York: Doubleday and Co., 1965

Notes

1 E-mail from Bill Wakefield, April 20, 2017, and following month for much of the personal information that follows.

2 From “On 45 Years’ Rest”

3 Telephone interview, Steven Goldleaf with Bill Wakefield, July 3, 2017

Full Name

William Sumner Wakefield

Born

May 24, 1941 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.