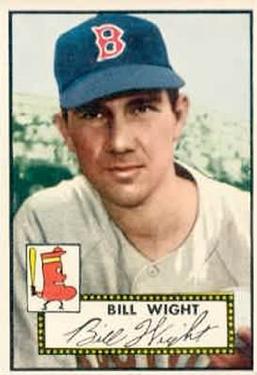

Bill Wight

Left-handed pitcher Bill Wight spent twelve seasons in the Major Leagues with eight different clubs. He appeared in 347 games, compiling a mediocre 77-99 won-lost record and a 3.95 earned run average. Wight does hold one record; however, it’s for batting, and it’s one he never took pride in. Pitching for the Chicago White Sox in 1950, Wight was hitless in sixty-one at-bats, the most at-bats by an American Leaguer in a season without getting a hit.

Left-handed pitcher Bill Wight spent twelve seasons in the Major Leagues with eight different clubs. He appeared in 347 games, compiling a mediocre 77-99 won-lost record and a 3.95 earned run average. Wight does hold one record; however, it’s for batting, and it’s one he never took pride in. Pitching for the Chicago White Sox in 1950, Wight was hitless in sixty-one at-bats, the most at-bats by an American Leaguer in a season without getting a hit.

Bill was born William Robert Wight on April 12, 1922, in Rio Vista, California, inland about 60 miles from San Francisco. His father, Bert, worked on the water as a launch operator and later as a shipping captain. Bert Wight was a California native. His wife, Laura (Quinn) Wight was from Oregon. The couple had two sons, Charles, born in 1914, and then Bill eight years later.

Bill attended Lafayette elementary school and Lowell Junior High in Oakland, and graduated from McClymonds High School in Oakland in 1940. The six-foot-one, 180-pound teenager was signed by legendary New York Yankees scout Joe Devine and played his first season as a professional in 1941 for the Idaho Falls Russets in the Class C Pioneer League.

“In California, a kid can play all year around. I used to haunt Bay View Park in Oakland,” Wight told sportswriter Will Wedge. “That must have been where Joe Devine saw me first. He’s the Yanks’ scout and a great organizer of kid teams. He got together the Yankee rookies along about 1938, and fitted us out in uniforms that were practically the same as those of the real Yanks. The only kid on the team over 18 was Russ Christopher. I was only 16, and maybe I wasn’t excited the day Devine went home with me and had my father sign an agreement that I wouldn’t sign up with any professional team but the big Yankees. I got $1,000 for that, and it seemed like all the dough in the world. A couple of years later, after I had turned 18, the Yankees sent my father and me a contract and I stepped out with Idaho Falls.”1 Bill later admitted that he was more interested in sketching than playing ball.2

There was a benefit to growing up when he did. “All the playgrounds were free and during the Depression, they’d give you equipment if you wanted. Sign out for it. You could play every day and it helped you develop faster.”3 Wight played outfield at first, but had a strong arm and soon turned to pitching. It wasn’t in high school that he got any real help; he learned the most playing semipro baseball, often against veteran ballplayers. “We were all in high school, 16 to 18, and we’d get the hell kicked out of us in some of those games by those old semi-pros, you know, but that’s who you played against. You learn when you hang a curve against a good hitter. In high school, a guy takes it for strike three. There’s a big difference. You learn quicker. And they’d tell you about your mistakes.”

The University of California made him Wight an offer, but he hadn’t been on a college track and said he didn’t think he had the grades. “I was an art major,” he said, and got straight A’s, but it was purely by taking art classes and no others. He met his future wife, Janice, in high school art class.

Yankees scout Devine had an edge, however. He would take a number of prospects on a bus down to Modesto on weekends and work them out, giving them experience, getting to know them and letting them and their families to get to know him.

Wight was 8-12 with Idaho Falls, in his debut 1941 season. He moved up to the Class A Binghamton (New York) Triplets in 1942, but the weather in upstate New York was too cold for him. He was shifted to the Class B Norfolk Tars in Virginia, where he went 7-5, with a 2.43 ERA. He was slated to pitch for the Kansas City Blues, one of the Yankees’ top farm teams, at the end of the year, but shoulder trouble ended his season a few weeks early. Wight took advantage of the extra free time and married Janice Irene Carlson on September 8.

In November 1942, Wight joined the U.S. Navy and served until his discharge in December 1945. The navy took over Oakland’s St. Mary’s College and made it into a preflight school, bringing in many pro athletes to help build a program. Wight’s primary duty was being the base mailman, and helping with physical training. There was, naturally, a baseball team organized. “Me and Charlie Gehringer managed the club and Bill Rigney was on shortstop,” he said.4 His overall record pitching for the St. Mary’s Pre-Flighters was 33-5.5

With the end of the war, the Yankees were unsure of what they had in terms of players available for the 1946 season, so they scheduled an early spring training in Panama. Bill was on the Newark Bears’ roster but had asked if he could train with the big-league team. Manager Joe McCarthy agreed on a bit of a hunch and was impressed by what he saw of Wight. “The southpaw operated with all the poise of a veteran, had plenty of stuff and made even the customarily wary and cautious McCarthy grow exuberant.”6

The New York World-Telegram’s Bill Roeder’s February 28 dispatch was headlined “Bill Wight Looks Like He Might Be That Southpaw Pitcher Yankees Need.” The New York Sun’s Will Wedge featured his pickoff move in a March 30 column headed “Rookie Wight Perfects Pickoff.” The opposition protested balk, but Wight was charged with only seven in all his time in the majors. He’d developed the move himself. “I used to watch Walter Mails in San Francisco,” he explained. “Mails was one of the best ever nipping guys off first. I studied the way he stood and how he glanced out of the tail of his eye and then swiveled his neck around. He was nifty. Once Mails picked five guys off first.”7

Despite so many players contending for spots on the club, Wight remembered everyone just being happy to be there. The Yanks purchased his contract from Newark four days before Opening Day, and Bill made his first appearance in Philadelphia on April 17, the second game of the 1946 season. He relieved starter Randy Gumpert in the bottom of the seventh after Bobo Newsom had executed the second successful squeeze bunt of the inning. McCarthy instructed Wight to pick Newsom off first base, which he did. But he failed to retire any of the three batters he faced and threw wildly on another pickoff attempt for an error.

Wight’s first of four starts that season was on April 20, against Washington at Yankee Stadium. He lasted 6 1/3 innings, and was charged with the 7–3 loss. Wight stayed with the Yankees all season. Appearing in fourteen games, he had a 2-2 record and a 4.46 earned run average.

Wight spent 1947 with the Class Triple-A Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He won sixteen games with a 2.85 ERA as the Blues cruised to a first-place finish. The Yankees recalled him on September 19, and he appeared in one game, a complete-game win in the final game of the year, against Philadelphia at Yankee Stadium.

Wight’s connection with the Yankees ended in 1948 when he was packaged as part of a late February trade with the White Sox that brought left-hander Eddie Lopat to New York. Unaware of the trade, Wight was driving from his home in Healdsburg, California to the Yankees camp in St. Petersburg, Florida. The White Sox trained in Pasadena, California.

“We’re just hoping Bill picks up a paper somewhere along the way before he gets too far,” said New York public relations man Red Patterson. “Otherwise, it’s going to be a long trip back.”8 The Chicago Tribune printed a helpful headline: “NOTE TO BILL WIGHT: GET IN REVERSE AND HEAD FOR CALIFORNIA.”9 It didn’t work. On February 29, Wight and his wife and son, Larry, (born in 1943), arrived in St. Petersburg after driving eight days cross-country. He learned of the trade from a gas station attendant in Clearwater, less than twenty miles from camp.

Wight was 9-20 with a 4.80 ERA in 223 1/3 innings for the last-place White Sox in 1948. He also led the league in walks with 135. His best game was a three-hit shutout of the Yankees on May 21. His first big-league RBI came on his game-winning single, breaking a scoreless tie in the bottom of the fifth.

There was an amusing sidelight: Jerry Coleman had known Wight since childhood and knew about his pickoff move, so when Wight was with the White Sox and Coleman with the Yanks, Jerry kept warning his teammates to be careful. The only Yankee Wight picked off that year was Jerry Coleman.10

Wight enjoyed a much better year in 1949, winning fifteen games and losing thirteen with a greatly improved 3.31 earned run average. Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau later told him he’d just missed making the All-Star team.

He started well in 1950; but he missed almost three weeks due to hemorrhoids, followed by an ailing elbow that developed in a loss to New York on July 28. He did manage to pitch at least 200 innings for the third consecutive season, but his record slipped to 10-16 despite a decent 3.58 ERA. This was the year Wight batted sixty-one times without getting a hit.

In October and November Wight took part in a 33-game postseason exhibition tour pitting the American League All-Stars versus the National League All-Stars and visiting twelve states and Canada. On December 10, Boston moved to bolster its pitching staff by trading for Wight and Ray Scarborough. Strangely, before the season began, Wight was named president of the New York Yankees Alumni Association. The association was the sole creation of Yankees scout Joe Devine, who named its presidents.11

After Wight was knocked out in his first five starts for Boston, he was pulled from the rotation and used as a reliever and spot starter from that point on. Also, opposing managers ratcheted up their complaints about Wight’s pickoff move to first base, claiming that he balked every time. By season’s end he was 7-7 with a 5.10 earned-run average.

Red Sox pitching coach Bill McKechnie was pleased with Wight’s attitude at spring training in 1952, but when it came time for a trade, Wight was made available. He was sent to the Tigers as part of a nine-player deal on June 3; his first start with his new club was a losing effort against the Red Sox on June 8. However, by July 5 he’d already registered two shutouts. Wight was stingier with runs for both teams that season, finishing 1952 with a combined ERA of 3.75 and a 7-10 record.

Wight was the first Tiger to sign his 1953 contract. Pitching coach Ted Lyons was hopeful that a little work on his defense could help him: “Wight got himself in a jam four times last year by not covering first base. We’ll work on that this spring,” Lyons said.12 Bill was sharp in spring training, but he faltered badly when the season started. His ERA for Detroit was 8.88 in thirteen appearances. Just a little over a year after the trade to Detroit, Wight was sent to Cleveland in an eight-player trade in June. He pitched just fifty-two innings for the season, split almost evenly between the two teams.

Wight missed the Indians’ trip to the World Series in 1954, though he did get a $1,000 Series share. He had trained with Cleveland in Tucson, but was sold to San Diego and spent all of 1954 pitching for Lefty O’Doul in the Pacific Coast League. He excelled against PCL batters, posting a 17-5 record with a 1.93 earned run average for the pennant-winning Padres. Wight led the league in both winning percentage and ERA, and was one of three pitchers named to the league’s All-Star team.

His work in the PCL propelled him back to the majors in 1955, where the Indians used him in seventeen games. Though Wight had pitched well in limited action, he was placed on waivers in mid-July and claimed by the Baltimore Orioles. For the year, he had only a 6-8 record, but his ERA was a sparkling 2.48.

Seen from the start as part of manager Paul Richards’ four-man rotation, Wight was the Orioles’ Opening Day starter in 1956, but was hit for four runs in one-third of an inning and then hammered for another four runs without getting a man out just four days later. He recovered from that abysmal beginning with his first of nine wins that season, a 5–1 seven-hitter against the Yanks on May 13. By December 1957, Wight found himself in the National League, after being sold to the Cincinnati Reds.

Bill Wight was a man who had a few different talents. He enjoyed playing chess on the road, when he could find a suitable opponent, and he was a very good sketch artist. The January 1, 1958, San Francisco Examiner shows Bill with a sketch he’d done of Ted Williams. While in Cleveland he’d supplied sketches to accompany a column Early Wynn wrote for a newspaper there. In 1952, thanks to a friend of Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, Bill had received a scholarship for a mail-order course from the Famous Artists School of Westport, Connecticut.

Cincinnati planned to use Wight in the bullpen in 1958, but after appearing in seven games, the Reds released him on May 20. The St. Louis Cardinals picked him up as a free agent the next day so they could have at least one lefty reliever on the staff. Wight won three games without a loss for St. Louis, but his earned run average was 5.02.

During the off-season he toured East Asia with the Cardinals, traveling to the Philippines, Korea, and Japan. After beating the Hawaiian All-Stars on October 12, 3–1, he was released by the Cardinals but welcomed to continue on the tour. He loved it, he told The Sporting News. “Wonderful, just wonderful. In fact, (the Japanese) want me to pitch in their league. I’m seriously considering that offer, too. It sounds very good, except for being so far away from home.”

Wight went on to talk about his hopes for a career in sports cartooning or commercial art. “Baseball put me in a position to return to my art work when I no longer can get anybody out.”13

In 1959 Wight worked briefly in one final season, pitching in four games for the PCL Seattle Rainiers and then retired. He worked for a while as a liquor salesman, but also enjoyed time at his ranch in Mount Shasta, California. From 1962–66, he was a scout in Northern California for the National League’s new Houston club, where he signed future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan. Wight was an area scout for the Atlanta Braves from 1967 to 1994 and signed more than a dozen players, including Dusty Baker, Dale Murphy, Bob Horner, David Justice, and Kevin Brown. He then served as a Major League scout for the Braves from 1995 through 1998. Bill and Janice Wight were at Mount Shasta when Bill died of a heart attack on May 17, 2007.

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Interview with Bill Wight by Ed Attanasio on September 11, 2003. Interview with Janice Wight by Bill Nowlin on February 18, 2010.

Thanks to Jim Sandoval for scouting information. Thanks to Eileen Canepari.

Notes

1. Unattributed column by Will Wedge, March 31, 1946 in Wight’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2. Sporting News, December 17, 1958.

3. Interview of Bill Wight by Ed Attanasio, September 11, 2003. All quotations attributed to Wight are from the interview with Ed Attanasio unless otherwise indicated.

4. Interview on July 14, 2005 available through the online American Association Almanac at http://www.americanassociationalmanac.com/billwight.php.

5. New York World-Telegram, March 1, 1946.

6. Sporting News, March 14, 1946.

7. Wedge clipping in the Wight’s Hall of Fame player file, op. cit. Mails was a left-handed pitcher with the Brooklyn Robins, Cleveland Indians, and St. Louis Cardinals in the teens and ’20s, and a longtime coach and scout afterward.

8. New York Times, February 26, 1948.

9. Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1948.

10. Online American Association Almanac, op. cit.

11. Sporting News, February 7, 1951. Devine died in late September.

12. Sporting News, January 14, 1953.

13. Sporting News, December 17, 1958. One of Wight’s cartoons, commissioned by The Sporting News, illustrates the feature on Wight and his art.

Full Name

William Robert Wight

Born

April 12, 1922 at Rio Vista, CA (USA)

Died

May 17, 2007 at Mount Shasta, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.