Billy Rhines

Using an effective submarine delivery, pitcher Billy Rhines won 113 games in nine major-league seasons. Like rookies Mark Fidrych in 1976 and Fernando Valenzuela in 1981, Rhines burst onto the big-league scene with phenomenal success. As a 21-year-old rookie on the Cincinnati Reds in 1890, he achieved an 18-2 record in his first 20 starts.

Using an effective submarine delivery, pitcher Billy Rhines won 113 games in nine major-league seasons. Like rookies Mark Fidrych in 1976 and Fernando Valenzuela in 1981, Rhines burst onto the big-league scene with phenomenal success. As a 21-year-old rookie on the Cincinnati Reds in 1890, he achieved an 18-2 record in his first 20 starts.

William Pearl “Billy” Rhines was a lifelong resident of Ridgway, a northwestern Pennsylvania town known for its thriving lumber industry. Born there on March 14, 1869, he was the son of George Washington Rhines and Nancy Helen (Moore) Rhines. George was a lumberman and owner of a Ridgway billiard hall.1 According to census records, Billy had at least nine siblings.2

Billy attended Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, but did not graduate. He left school to play professional baseball for teams in Binghamton, New York, and Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1888, and in Davenport, Iowa, the following year. He was “a young and ambitious pitcher with good curves and plenty of speed,” a right-hander who stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 170 pounds.3

On June 28, 1889, Rhines pitched all 15 innings in a 6-4 victory over Springfield (Illinois); he struck out 12 batters in the contest.4 Six days later, he fanned nine in a three-hit shutout of Burlington (Iowa).5 In October 1889, the Cincinnati Reds of the National League signed him and his Davenport batterymate, Jerry Harrington.6

Rhines did not receive a decision in his major-league debut on April 22, 1890; he allowed two runs in four innings of relief facing the Chicago Colts.7 Then, with Harrington as his catcher, he won six consecutive starts in impressive fashion: a three-hit shutout of the Cleveland Spiders on April 30, a five-hitter against the same team two days later; a triumph over the Colts on May 7, followed by a three-hitter against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys on May 10; and a pair of victories over the Philadelphia Phillies on May 16 and 19.8 The youngster is the best pitcher in league, opined Phillies manager Harry Wright.9

Rhines’s winning streak was broken on May 22 when the Reds made five costly errors and fell 6-4 to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms.10 But he won his next seven starts, including shutouts of Cleveland and Chicago, and his record stood at 13-1 on June 17. He is a “full-blown phenomenon,” said the Cincinnati Enquirer.11 “Rhines was discussed in parlors, in bar rooms, in street cars, in the hotels, on the streets, in fact, it was Billy Rhines here, there and everywhere.”12

Rhines delivered “a bewildering dish of outcurves, inshoots, drops, rise balls and straight balls” with “remarkable speed and command of the ball.”13 He alternated “underhand” pitching with “high-arm throws.”14 His rise ball was “a beauty”: “It shoots along about a foot from the ground, until near the plate, when it suddenly rises.”15 A batter who managed to hit it usually popped it up.16

Harrington also drew praise. He and Rhines knew “each other’s signs as well as a magician and his female attendant,” and Rhines attributed much of his success to his talented catcher.17 Harrington “had no trouble in handling” Rhines’s “underhanded shoots” and was “able to throw to the bases from a squatting position, a novelty at the time,” wrote historian Lee Allen.18 Off the field, Rhines and Harrington were “sensible young ballplayers,” who “do not intend to throw away their chances by indulging in dissipation [alcohol abuse] or bad hours.”19 But that would change.

Rhines lost 4-2 to the Boston Beaneaters on June 20, but reeled off five more victories from June 25 to July 7, including two wins over the New York Giants, beating future Hall of Famers Mickey Welch and Amos Rusie.20 “Rhines is a cool-headed, quiet player,” said Reds manager Tom Loftus. “He has won 18 of the last 20 games he has pitched and to his credit let it be said he never gets the ‘big head.’”21

But the heavy workload took a toll on the rookie, who complained of a sore arm beginning in mid-June.22 From July 9 to August 1, he lost nine of 10 decisions, dropping his season record to 19-11. He returned to form on August 4, winning his 20th game, a 7-5 victory over the Phillies.23

Cy Young made his major-league debut with the Cleveland Spiders on August 6 and defeated the Chicago Colts, 8-1. Three days later, he and Rhines dueled for 10 innings, with Young coming out on top, 5-4.24 Rhines and the Reds avenged the loss on August 16, with a 10-0 thrashing of Young and the Spiders; it was Young’s first major-league defeat.25

Rhines finished the 1890 season with a 28-17 record, six shutouts, and a league-best 1.95 ERA. He worked 401⅓ innings during the regular season and pitched in three postseason exhibition games.26 Rarely has a pitcher accomplished so much in his rookie year. His 11.4 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) in 1890 are the most in one season in Reds history through 2016.27

His sterling first season was followed by an up-and-down sophomore year. On May 12, 1891, Rhines surrendered 18 runs to the Brooklyn Grooms; his pitches “floated up to the bat” and the Grooms drove them “to all parts of the lot.”28 But on June 1, he fired a three-hitter in a 5-2 victory over future Hall of Famer Kid Nichols and the Boston Beaneaters; the “efforts of the Boston batsmen to gauge Rhines’s delivery” were “absolutely futile.”29 Eight days later Rhines fanned 10 batters in a 9-3 triumph at Philadelphia. The Phillies’ Ed Delahanty, one of the greatest hitters of the era, struck out four times.30

Bothered by a sore arm, Rhines lost 16-8 at Chicago on July 22.31 Yet on August 3, he hurled his only shutout of the season, beating Nichols and the Beaneaters again.32 Rhines finished the year with a 17-24 record in 372⅔ innings and a respectable 2.87 ERA.

But Rhines’s career spiraled downward the next year. The trouble began in March of 1892 when he suffered a broken collarbone in a wrestling match.33 He tried pitching in Cleveland on April 23, but was removed from the game after allowing five runs in the first inning.34 The Reds laid him off without pay until he “gets well enough to permit him to do his usual work.”35

To make matters worse, Rhines, Harrington, and Reds outfielder Eddie Burke were out late one night in May when they became “stupidly drunk,” and Rhines and Burke fought each other “in a disgraceful, drunken brawl.” The Reds fined Harrington and Burke $100 each and suspended Rhines indefinitely.36 After another drinking incident a week later, Harrington, too, was suspended.37 Rhines said defiantly, “I am not compelled to play ball for a living. My folks are well-to-do. My father runs three sawmills at Ridgway and I can go home any time I want to. A rest may do me good.”38

The Reds reinstated Rhines and Harrington in July. In his first game back, on July 13, Rhines hurled a four-hitter in a 3-1 victory over the Brooklyn Grooms.39 A week later, with Harrington as his catcher, he defeated the Senators, 3-2, in an 11-inning contest at Washington.40 In the third inning, Rhines slugged a solo home run, the only homer of his career.

But the success was short-lived. In Philadelphia on July 26, Rhines allowed 18 runs in five innings of work in a 26-6 loss to the Phillies.41 A week later in Louisville, he was “an easy mark” for the Colonels, who “knocked the ball all over the lot” in an 11-4 pasting of the Reds.42 And in Cleveland on August 9, Cy Young and the Spiders prevailed 8-5 over Rhines and the Reds.43

The final straw came on August 17 in Cincinnati. Rhines was taken out of the game after giving up nine runs in three innings to the New York Giants.44 After the game, the Reds released both Rhines and Harrington.

The Louisville Colonels gave the pair a one-month trial in 1893, but both men failed the test and were let go. Rhines lost four of five starts, and in 31 innings, he walked 19 batters and struck out none. Harrington batted .111 in 10 games, and he and Rhines were fined “for imbibing too freely.”45 Upon his release, Harrington’s career ended, but Rhines would work his way back to the majors.

In 1894 Rhines pitched 406⅔ innings and compiled a 25-19 record for Grand Rapids (Michigan) of the Western League. It was a hitters’ league, and Rhines allowed a whopping 436 runs during the season. Nonetheless, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, who were willing to give him another chance. The Reds were desperate for help after their pitching staff recorded a league-worst 5.99 ERA in 1894.

An interesting side note to the 1894 season is that Joe McGinnity, a 23-year-old pitcher on the Western League’s Kansas City team, observed Rhines’s submarine style with keen interest. McGinnity would go on to a Hall of Fame career by emulating Rhines’s delivery.46

In 1895 Rhines went 19-10 with a 4.81 ERA (a tad worse than the league ERA of 4.77), and his 19 wins led the Reds. One of the victories came at Cleveland on August 15, when he defeated Cy Young, 4-3.47 He continued his rivalry with Young, winning 8-4 on April 24, 1896, but losing 2-1 eight days later.48 On September 18, 1897, in the first game of a doubleheader, Rhines lost 6-0 to Young, who threw a no-hitter.49

On May 6, 1896, Rhines pitched one of the best games of his career, a two-hit shutout of the Boston Beaneaters. The Boston hitters “appeared in a dazed condition when they were at the plate”; they looked at Rhines’s pitching “in open-mouthed amazement, like it was something they had never seen before.”50

Rhines pitched another dazzling two-hit shutout on May 20, against the Phillies.51 But misfortune struck four days later: A “hot liner” off the bat of Louisville’s Doggie Miller hit the middle finger of Rhines’s pitching hand, fracturing the digit.52 The injury caused him to miss more than two months of the 1896 season. He finished the year with an 8-6 record and a league-leading 2.45 ERA in 143 innings.

The next season Rhines compiled a 21-15 record with a 4.08 ERA. On August 7, 1897, he “had not only speed, but grand command and the best use of his famous underhand ball,” in a three-hit shutout of the Louisville Colonels.53 Louisville’s Honus Wagner, a 23-year-old rookie, went hitless in the game.

Rhines pitched for an All-American team on a barnstorming tour with the Baltimore Orioles from October to December, 1897.54 In the midst of the tour, the Reds traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In 1898 Rhines went 12-16 for the Pirates with a 3.52 ERA, but he was suspended in September after throwing a wild weekend party in New York for returning veterans of the Spanish-American War. Rhines, himself a fine marksman, was fascinated by the war and delighted in interacting with the servicemen. Throwing the party was an act of patriotism, Rhines argued. Pirates manager Bill Watkins disagreed and suspended him for the remainder of the season.55 “Rhines is anything but a rowdy,” said the Pittsburgh Press. “He is intelligent and ordinarily well behaved.”56

Rhines pitched two brilliant games in 1899. He hurled a two-hitter against the Chicago Orphans in an 11-1 victory on May 17; “he had that underhand raise ball of his going,” and the Orphans “never got near it.”57 And two weeks later, he defeated the Washington Senators, 5-1, with a four-hitter.58 But three times he was knocked out of a game after allowing six or more runs in only two innings of work. After the third time, against the New York Giants on June 22, the Pirates released him.59 He received offers from several teams but decided to rest for the remainder of the year.60

Rhines’s father died in September of 1899 and left him an inheritance.61 Perhaps this affected his decision to leave baseball and stay in Ridgway and work as a lumberman.62 Except for a brief stint in 1901 with the Grand Rapids team of the Western Association, Rhines was done with professional baseball.

A longtime bachelor, Rhines got married in 1912 at age 43, to 23-year-old Kozie Lorraine Milliron.63 By 1920 they had four children and Billy operated a taxi service.64 After a long illness, he died of heart disease on January 30, 1922, in Ridgway, at the age of 52.

Though Rhines was not the first submarine pitcher, he was one of the most influential. Joe McGinnity compiled a 28-16 record as a rookie on the 1899 Baltimore Orioles using “an underhand delivery very much on the order of the veteran Rhines.”65 McGinnity’s record was reminiscent of Rhines’s 28-17 mark nine years earlier. “The submarine motion enjoyed a vogue of popularity in the early twentieth century,” wrote historian Peter Morris, “with such pitchers as McGinnity, Bill Phillips, Deacon Phillippe, Jack Warhop, and Carl Mays experiencing success with it.”66

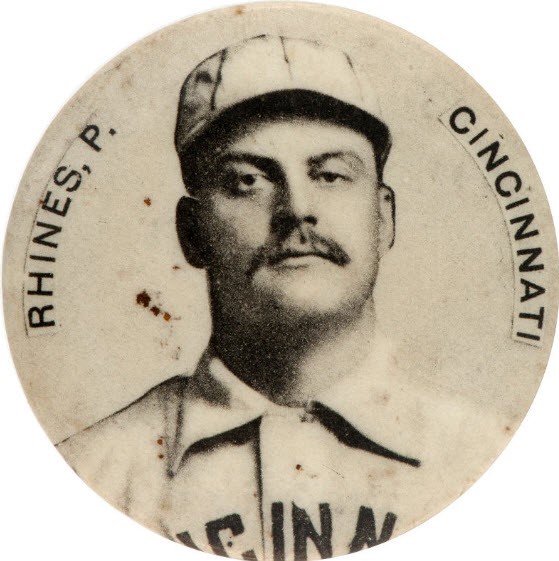

Photo credit

1¼-inch Cameo Pepsin Gum pin, made by the Whitehead & Hoag Company, circa 1898

Notes

1 Elk County Advocate (Ridgway, Pennsylvania), October 9, 1873.

2 1870 and 1880 US Censuses.

3 Sporting Life, July 25, 1888.

4 Davenport (Iowa) Daily Republican, June 29, 1889.

5 Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1889.

6 Sporting Life, October 30, 1889.

7 Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1890.

8 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 17, 20, 1890; Philadelphia Times, May 3, 1890; Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1890; Pittsburgh Press, May 11, 1890.

9 Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1890.

10 Sporting Life, May 24, 1890.

11 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 18, 1890.

12 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 2, 1890.

13 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 3, June 3, 1890.

14 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 23, 1890.

15 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 1, June 3, 1890.

16 Sporting Life, July 12, 1890.

17 Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 1, 1890; Sporting Life, January 24, 1891.

18 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006), 37.

19 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 22, 1890.

20 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 21, July 2, 5, 8, 1890; Philadelphia Times, June 26, 1890; Sporting Life, July 5, 1890.

21 Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 9, 1890.

22 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 13, 1890.

23 Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 5, 1890.

24 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 10, 1890.

25 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 17, 1890.

26 Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 8, 1890; Sporting Life, October 18, 1890.

28 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 13, 1891.

29 Boston Post, June 2, 1891.

30 Philadelphia Inquirer, June 10, 1891.

31 Sporting Life, July 18, 25, 1891.

32 Boston Post, August 4, 1891.

33 Sporting Life, March 26, 1892.

34 Philadelphia Inquirer, April 24, 1892.

35 Sporting Life, April 30, 1892.

36 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 6, 1892.

37 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 1892.

38 Ibid.

39 Sporting Life, July 16, 1892.

40 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, July 21, 1892.

41 Philadelphia Inquirer, July 27, 1892.

42 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 1892.

43 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 10, 1892.

44 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1892.

45 Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1893.

46 Don Doxsie, Iron Man McGinnity: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 35.

47 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 16, 1895.

48 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 25, 1896; Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 3, 1896.

49 Sporting Life, September 25, 1897.

50 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 7, 1896.

51 Philadelphia Times, May 21, 1896.

52 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 25, 1896.

53 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1897.

54 Sporting Life, October 30, November 27, December 4, 1897.

55 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 7, 1898; Pittsburgh Press, September 21, 1898; Sporting Life, October 1, 1898.

56 Pittsburgh Press, March 12, 1899.

57 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 18, 1899.

58 Washington Star, June 1, 1899.

59 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 23, 1899.

60 Pittsburgh Press, June 24, 1899; Sporting Life, August 12, 1899.

61 Sporting Life, November 18, 1899.

62 1910 US Census.

63 Ancestry.com.

64 1920 US Census.

65 Washington Star, June 17, 1899.

66 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 82.

Full Name

William Pearl Rhines

Born

March 14, 1869 at Ridgway, PA (USA)

Died

January 30, 1922 at Ridgway, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.