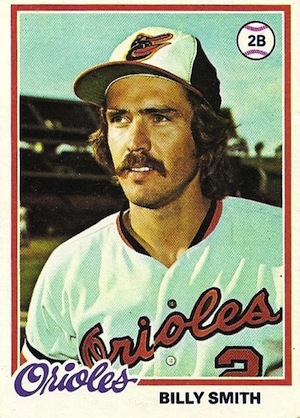

Billy Smith

November 1976 was a difficult month for fans of the Baltimore Orioles. After an 88-win, second-place finish in the just-completed season, the advent of free agency during the offseason stood to dramatically alter the team’s chemistry, and within a ten-day period the worst-case scenario was realized: On the 19th of November, 20-game winner Wayne Garland joined the Cleveland Indians; then, on November 24 Gold Glove and All-Star second baseman Bobby Grich returned to his Southern California roots by joining the California Angels; and finally, on November 29, perennial All-Star and future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson, arguably the game’s biggest superstar at the time, left the team after just one season to become a millionaire with the New York Yankees. Just like that, Baltimore was bereft of 20 wins, 40 home runs, and some brilliant infield defense.

November 1976 was a difficult month for fans of the Baltimore Orioles. After an 88-win, second-place finish in the just-completed season, the advent of free agency during the offseason stood to dramatically alter the team’s chemistry, and within a ten-day period the worst-case scenario was realized: On the 19th of November, 20-game winner Wayne Garland joined the Cleveland Indians; then, on November 24 Gold Glove and All-Star second baseman Bobby Grich returned to his Southern California roots by joining the California Angels; and finally, on November 29, perennial All-Star and future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson, arguably the game’s biggest superstar at the time, left the team after just one season to become a millionaire with the New York Yankees. Just like that, Baltimore was bereft of 20 wins, 40 home runs, and some brilliant infield defense.

With little money to spend to replace the three departed players, general manager Hank Peters improvised. On the mound, young hurlers Mike Flanagan and Dennis Martinez would replace Garland’s victories; Peters obtained veteran outfielder Pat Kelly from the Chicago White Sox to play left field, allowing the club to return unspectacular but steady Ken Singleton to Jackson’s position in right field; and finally, with Triple-A phenom Rich Dauer a possibility to replace Grich, Peters signed as a free agent from the California Angels a little-known utility infielder named Billy Smith to compete with Dauer for the second-base position. What followed were, in Smith’s words, “the best three years I ever had playing ball” and one of the hottest months by an Oriole hitter that Baltimore fans had ever seen.

Billy Ed Smith (not Billy Edward, he pointed out in a telephone interview, noting that many online sources are incorrect) was born on July 14, 1953, in the village of Hodge, in northern Louisiana, to Billy W. and Carol Smith. His father was an outstanding athlete, good enough at the age of 16 for the Brooklyn Dodgers to want to sign him. Billy’s mother refused to allow him to sign with Brooklyn, so instead he enlisted in the Air Force, and eventually became an athletic director. Billy W. met his future wife in Louisiana, where Billy Ed was born. The family (Billy Ed had a brother and two sisters) finally settled at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. After his discharge from the Air Force, Billy W. spent 27 years in the federal Civil Service, including 20 years as the civilian athletic director at Lackland AFB. He excelled as a fast-pitch softball player, traveling the country in competition against players like pitcher Eddie Feigner, of the renowned “King & His Court.” A first baseman, Billy W. was, according to his son, “a great hitter.” Comparing his own career, Billy Ed said, “I got the speed and the defense, he could hit.”

Growing up in San Antonio, Smith proved a natural athlete. After following the customary baseball path through Little League and Pony League, by the time he entered San Antonio’s John Jay High School he was well-schooled in the fundamentals. A shortstop, over the four years that he lettered in baseball he was named to the All-San Antonio and All-District teams, and in 1970 was selected to play in the prestigious North-South All Star game. (Smith also twice lettered in basketball.) By his sophomore year scouts were present at all of Smith’s games, and by his senior season Smith was almost assured of being a first-round draft choice. However, during that season a bad hop broke his thumb, and as a result he fell to the third round in the June 1971 amateur draft, and was selected by the Angels. After signing with Angels scout Rex Carr, Smith, a month shy of his 18th birthday, left for Idaho Falls, in the rookie Pioneer League, to begin his professional career.

In most respects Smith’s 59 games in Idaho were a microcosm of his six seasons in the majors. Already a polished fielder, that season he led the league in putouts and assists by a shortstop despite struggling with the thumb injury, which had not fully healed and was largely responsible for his 36 errors (mostly throwing) and dismal .881 fielding average. At the plate Smith often struggled; years later he characterized himself as “hot and cold as a hitter” throughout his career, and a “streak hitter” who was “pretty good with runners on base.” Yet while he batted just.229 at Idaho Falls, Smith led the league in stolen bases.

Over the next two seasons, as Smith rose through the Angels’ system from Class A teams in Stockton and Salinas, California, to Double-A El Paso, the maturing teenager’s skills steadily improved, and the Angels took notice. His batting and fielding improved steadily, and without an established shortstop in the Angels’ everyday lineup, Smith’s progress boded well for his future with the organization, and he was knocking on the door to the major leagues.

On opening day of the 1974 minor-league season, the soon-to-be 21-year-old Smith was the starting shortstop for the Angels Triple-A affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, the Salt Lake City Angels; to get there, he had won a spirited “battle”1 for the position with another future Angels shortstop, Orlando Ramirez. The local press was excited by Smith’s prospects, calling the “rangy kid … something new and refreshing.”2 He was “one of several Salt Lake City players blessed with unusual speed.”3 Particularly exciting was Smith’s .331 batting average the previous year at El Paso, a performance which undoubtedly gave him an edge in the competition. So too, perhaps, did his flexibility at the plate, where he was a switch-hitter. “I started to switch-hit when I was eight years old,” Smith said. “That came about as a result of me being mad at my dad. I was playing minor little-league ball at the time and the majors called me up. But my dad didn’t think I was ready and said no. I got mad at him and he wound up giving me a spanking. … I was always a left-handed hitter and decided I would get even with my dad so I strictly batted right-handed for the next four weeks. And I did pretty well. Then when I was a sophomore in high school I decided to switch-hit permanently and have been doing it ever since. … It makes no difference which way I bat. Last year [1973] I hit four home runs right-handed and four left-handed, but I think I had more power from the left side [according to Baseball-Reference.com, Smith actually hit a combined six home runs that season].”4 It’s worth noting that of Smith’s 17 career major-league homers, only one was hit as a right-hander.

At Triple-A, Smith had a difficult time reproducing the previous season’s lofty batting average, which began to seem little more than an aberration, as Smith’s batting average through 40 games was a paltry .206. Then he broke a rib and resurrected his season. To allow Smith to recover from his injury without undue pressure, the Angels sent him back to El Paso, assuring him that when he was healed, they’d return him to Salt Lake City. As it turned out, however, despite being “visibly shaken”5 and considering going home when the team kept him at El Paso for the remainder of the season, Smith recovered his bearings and delivered a blistering .335 batting average in 62 games (playing for the first time exclusively at first base and second base), and once again proved he was a top prospect. When the 1975 season began, Smith found himself on the Angels’ major-league roster.

Smith joined a team with little history of winning. Since entering the American League in 1961 as an expansion franchise, the Angels had never finished higher than third place or won as many as 90 games. In 1974 hopes had been raised when Dick Williams, who had managed the Oakland A’s to successive World Series wins in 1972 and ’73 before abruptly bolting the team after the World Series, assumed the Angels’ helm on July 1, piloting them through the remainder of that season. Now Williams was building a youthful team, one that placed a premium on fundamentals. “I maintain an open mind about several positions,” Williams said during spring training, “and about the only thing we feel is now set is our starting pitching rotation.”6

At shortstop five players vied for the starting position: Smith; Dave Chalk, the previous year’s starter before being injured; Rudy Meoli; Orlando Ramirez; and 1974’s number one draft pick, Mike Miley. In the end, Ramirez and Smith, rivals for the position the year before at Triple-A, won the job, so Smith opened the 1975 season as a major leaguer. Relegated to pinch-running and as an occasional defensive replacement, Smith appeared in just ten of the team’s first 21 games.Ramirez began to struggle defensively, and on May 2 at Texas, in the team’s 22nd game, Smith made his first start, singling in his first two at-bats off the Rangers’ Steve Hargan. On May 8 in Oakland, he replaced Ramirez in the third inning and over the next five weeks made 33 starts, during which he struggled to a .217 average.

One of those games was particularly memorable. On June 1 at Anaheim, Smith was the starting shortstop when teammate Nolan Ryan pitched his fourth no-hitter, defeating the Baltimore Orioles, 1-0. On the final out of the game, Smith recalled, “Grich was up for Baltimore, with a 3-and-2 count.” As Smith waited tensely at shortstop, Ryan poised for the final pitch, and Smith wondered, “What’s he gonna throw?” Ryan had gotten Grich to two strikes by throwing fastball, fastball, and then … “[Ryan] threw him a changeup. That’s how I got into Cooperstown,” Smith recalled with a chuckle. “My name is on the lineup card that’s in the Hall of Fame.” It was to be the highlight of Smith’s brief tenure with the Angels.

If Ramirez proved a less than capable fielder in 1975, so too, surprisingly, did Smith, who also finished the season with a .203 batting average in 59 games. By the All-Star break the two had combined for 29 errors, Ramirez 16 in 41 games, and Smith 13 miscues in 50 games. In the first week of July Williams sent both shortstops to Salt Lake City and promoted rookie Mike Miley, who finished the season as the starter. For Smith, it was an ominous sign, and although he made the team again the following spring, it effectively ended his prospects with the Angels. When he finally gained lasting success in the majors, Smith had changed not only his uniform, but also his position.

In 1976 Smith and Ramirez again made the club out of spring training, and once again it was Ramirez who was named the starter. Neither, however, made it to the All-Star break. On May 4, After batting just eight times in 13 games (none as a starter) and committing three errors in eight chances at shortstop, Smith was sent back to Salt Lake City. Two weeks later Ramirez joined him. The two-year experiment with Ramirez and Smith was finished. So, too, was Smith’s time in Anaheim.

That winter Smith filed for free agency, and on February 8, 1977, he inked a deal with Baltimore, For the next three years, Smith wore the black and orange uniform of the Orioles. (About the Angels’ “losing” Smith so they could sign high-profile free agents, the following spring Smith said, “I’m not going to say they did and I’m not going to say they didn’t. They could have done a lot of things.”7)

In the spring of 1977 the Orioles trained in Miami, Florida. With little pressure and a new $25,000 contract (plus a bonus of the same amount), Smith said, “This year I’m so much more relaxed. Sometimes you just need a different atmosphere.”8 His training-camp performance reflected his stress-free environment; in exhibition games he batted over .300 and impressed the coaching staff with his defensive flexibility and ability to hit to all fields. There was little doubt how Smith would be used: With both the brilliant Mark Belanger and Belanger’s up-and-coming backup, Kiko Garcia, on the team, Smith wasn’t going to play much shortstop. Yet one of the reasons Smith had chosen to sign with the Orioles (he had been selected by ten teams in the re-entry draft), he said, was that “I knew they had a rookie [Rich Dauer] at second base and that if something happened I might be able to move in.”9

Dauer, a much-heralded rookie, was expected to be a more than capable replacement for Bobby Grich. But things didn’t quite go as planned. As the Orioles struggled out of the gate to a 1-4 record, Dauer likewise performed miserably, going 0-for-16 at the plate over that span (he ultimately began the year 0 for 26). So, as the Orioles arrived in Arlington, Texas, to face the Rangers, Weaver decided to shake things up. On April 17, in the first game of a doubleheader, facing future Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven, Smith started in place of Dauer. The move paid immediate dividends. Playing in his home state with his parents and brother in attendance, Smith went 3-for-4, singling twice and connecting for his first career home run. Then, in the second game, Smith again started, against another future Hall of Famer, Gaylord Perry, and again tallied 3-for-4 (all singles), with another RBI. Afterward, Smith said that his 6-for-8 performance was especially gratifying because his father had been there. “I don’t know what it was,” Smith said, but I’ve never hit before when he was watching. … It’s funny, but I got my first two major-league hits in this ballpark and my mom was here, but my father couldn’t make it. He had never seen me get a hit before today.” To which his father replied, “I think he hated to see me come to the ballpark.”

As it turned out, Smith was just getting started. When the Orioles returned home the next night to face Cleveland, he remained in the lineup at second base, as he would throughout the three-game series. That night he went 0-for-3, but the following night, against yet another Hall of Famer, Dennis Eckersley, he collected three more hits, including his first double. That was another special game. With the score tied, 2-2, and left-handed reliever Dave LaRoche on the mound for Cleveland, Dauer batted for Smith in the bottom of the ninth and ended the inning called out on strikes. In the top of the tenth, though, the Indians scored three runs, so the Orioles came to their last at-bat trailing 6-2. After a run was scored, Baltimore put two men on base with one out and then legendary Brooks Robinson, pinch-hitting, delivered a dramatic three-run homer to win the game. It was the 268th and last home run of Robinson’s Hall of Fame career.

By April 20, Smith had amassed an offensive line of .476/.522/.667. Most importantly, the Orioles had won all five games Smith had started, to improve to 6-4. Five days later the Yankees came to Memorial Stadium, and over that three-game set Smith, still starting, went 6-for-12 with four runs scored. By the final day of April his slash line read .386/.460/.500. It had been quite a performance, one that Smith would rarely repeat. When the dust cleared in April 1977, he had delivered 17 hits in 44 at bats, scored seven runs and driven in five, collecting along the way his first big-league home run. Over the remainder of the season he tailed off dramatically, eventually finishing at .215, while Dauer righted his performance and finished at .243. Smith’s 109 games played and 367 at-bats in 1977 were the most he accrued in a single season.

After such a resounding first month of his Orioles tenure, over the next two seasons, as Dauer matured at second base and settled into the position full-time, Smith filled in admirably when needed and delivered the occasional burst of offense. On May 26, 1978, with the Orioles trailing Cleveland, 3-2, Smith tied the game when he led off the bottom of the eighth inning with his first home run of the season, against Indians starter Rick Wise; then, in the ninth, with two aboard and two outs, he doubled off Wise to win it. That barrage was part of a nine-game hitting streak during which Smith went 17-for-30 to raise his batting average from .227 to .296. Later, on June 2, at Seattle’s Kingdome, he hit the first of two career grand slams, in a game the Orioles won, 10-9. Finally, on September 28, at Cleveland in perhaps the best performance of his career, Smith produced a double, triple, and home run with six RBIs. In 1979 he played in just 68 games but set career highs with 6 home runs, 33 RBIs, and a .434 slugging average. During the World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, Smith started Games One and Two at Memorial Stadium, pinch-hit for Dauer in two other games, and finished his only World Series 2-for-7 with a run scored and no errors in the field.

In the spring of 1980, in what Smith in 2013 recalled as “the only thing I ever regretted,” he filed for salary arbitration. It was, he recalled, “a tough thing to do.” The Orioles offered Smith a raise, from $47,000 to $65,000; Smith asked for $95,000. The Orioles prevailed. For Smith, it was a slap in the face.10

“They tried to embarrass me at the hearing,” Smith said at the time. “The Orioles made it sound like I didn’t do anything last year. If they don’t think that much of me, why don’t they trade me?”11 Reportedly “humiliated” and “despondent”12 by the arbitrator’s siding with the team, Smith said, “If I mean so little around here, I want to leave.” Subsequently, on April 3, with rookie Floyd Rayford enjoying a good spring, the Orioles released Smith. His Orioles career was over.

On June 8 Smith signed with the Philadelphia Phillies, who sent him to their Triple-A affiliate in Oklahoma City. On March 23, 1981, the San Francisco Giants, now managed by Frank Robinson, who had been a coach for the Orioles, purchased Smith from the Phillies. He played his last major-league season in San Francisco, appearing in just 36 games and posting a .180 batting average. After the season he retired.

In 370 games over parts of six seasons, Smith batted .230/.297/.335, with 17 home runs and 111 RBIs. In 255 games as a second baseman, he fielded .987.

With his baseball career finished, and wanting to get away from the game, Smith entered the business world. During his time in Baltimore he had made weekly appearances on a local radio show, so he was a good public speaker. In California, he had a cousin who owned a roofing supply business, and Smith put his speaking skills to use there working in sales. In 1982 he began his own roofing business in San Antonio, which he sold in 1987. After that, Smith worked in the wholesale building-supply business, and in 2004 went to work for the ABC Supply Company, a wholesaler of roofing, siding, and windows, for whom he was still employed in 2013.

In 2009 Smith remarried. Over the years he had worked hard to put his three children, Ashlee, Billy Jr., and Tyler, through college, and with that done, he had time to relax. Besides playing golf with his customers, Smith enjoyed hunting and fishing, and particularly his main love, riding his Harley – “I love to ride all over,” he said. In 1994, after staying away for a good ten years, Smith re-engaged with baseball, returning to the game through the alumni association, participating in clinics and working with youth. As of 2013 he lived in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and spent time with many of his former teammates and colleagues, such as Don Stanhouse and Doyle Alexander, both of whom live nearby.

Sources

Newspapers

Annapolis (Maryland) Capital

Cumberland (Maryland) News

Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times

El Paso Herald Post

Frederick (Maryland) News Post

Long Beach (California) Press Telegram

Oxnard (California) Press Courier

Salt Lake Tribune

The Sporting News

Online

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Archives

Billy Smith player file in the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Personal correspondence

Telephone interview with Billy Smith, August 6, 2013

Notes

1 El Paso Herald, March 25, 1974.

2 Salt Lake Tribune, April 4, 1974.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 El Paso Herald, July 18, 1974.

6 Associated Press via Lima (Ohio) News, March 13, 1975.

7 Cumberland (Maryland) News, April 22, 1977.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 The Sporting News, March 22, 1980.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

Full Name

Billy Ed Smith

Born

July 14, 1953 at Hodge, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.