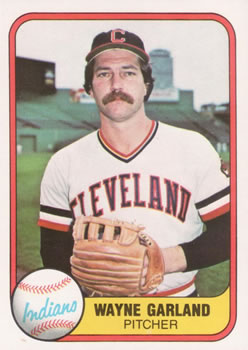

Wayne Garland

“My father-in-law said I wasn’t worth that much,” said Garland, “and he was right. No pitcher is worth that based on one season. But if they offer it to you, naturally you’re going to take it.”1

“My father-in-law said I wasn’t worth that much,” said Garland, “and he was right. No pitcher is worth that based on one season. But if they offer it to you, naturally you’re going to take it.”1

Wayne Garland wore “it” like an albatross around his neck. “It” is how baseball fans in general — and Cleveland Indians fans specifically — remember him best: the 10-year, $2.3 million contract that Garland signed with the Indians in November 1976.

Because of arm and shoulder injuries, Garland pitched just one full season with the Indians and parts of four others before he was released on January 29, 1982. The balance of his pact was paid to him over five years, after his pitching days were long over.

At the time, it was the third-biggest free agent deal (after the Yankees signed Catfish Hunter and Reggie Jackson). The Indians could ill afford to receive so little in return. But after a 20-win season for Baltimore in 1976, Garland was one of the top pitchers on the market. He had just turned 26 years old; seemingly, he could be the pitcher around which to build a staff.

Unfortunately, it was another chapter in the dreary history of the Tribe. The Indians played in an oversized, unsightly stadium and they couldn’t draw fans to their games, much less attract quality free agents to the club. Any free agent the Indians signed had to be a bullseye. The Garland contract not only yielded little but also left the club on a shoestring budget without laces for years.

Marcus Wayne Garland was the youngest of four children (the others were Stanley, Kathi and Connie) of William and Marie (née Murphy) Garland.2 He was born on October 26, 1950, in Nashville, Tennessee. Bill Garland was a veteran of the United States Army, serving in the Philippines. He worked at the Ford Glass Plant in Nashville and his family business, Garland Body Shop.3

Wayne Garland was a two-sport star as a guard in basketball and a starting pitcher in baseball at Cohn High School in Nashville. In baseball, Garland was a three-time selection of the All-Metro League of the Nashville Interscholastic League (NIL). The Black Knights captured the league championship when Garland pitched three complete games in five days. The right-handed workhorse faced 88 batters and struck out 24, walked five, gave up ten hits and surrendered only one earned run.4

In the seven-inning title game against defending champ Madison, Garland faced 22 men and hurled a two-hitter, leading the Black Knights to a 1-0 victory. With major league scouts in attendance, Garland capped a 6-1 senior season. “My arm felt tired around the fourth or fifth inning,” said Garland. “I didn’t use my fastball as much but relied more on a knuckler and a curve.”5

In addition, Garland played second base and outfield when he wasn’t on the hill. He batted .333 for the season and drove in 17 runs his senior year.

On June 7, 1968, Garland was selected with the 93rd overall pick in the fifth round by the Pittsburgh Pirates. He did not sign a contract; instead he opted to enroll at Gulf Coast Junior College in Panama City, Florida. Before he left for college, pitching for Nashville Post 5 in the Connie Mack League on August 1, he struck out 20 of 21 batters in a perfect-game 2-0 victory over Dyersburg (also seven innings). “I knew I was working on the perfect game in the seventh and I was scared all the way,” said Garland. “In fact, I have chills right now. I think this has to be the best game I’ve thrown this year. I had good stuff, but there was no particular reason why tonight was better than the others.”6

Garland pitched a second no-hitter on August 27 against Cincinnati to run his record to 15-2 on the year for Post 5. He struck out nine but walked eight in the 3-0 win.7 He was named to the Connie Mack “All-World” team.8

The secondary (winter) baseball draft was held on February 1, 1969. At that time, the major-league draft was broken into two phases: the first was to select players who just graduated, mostly high school and junior college players. The secondary phase was for those players who were previously drafted by other teams, but had not signed a contract. Garland was the first player chosen in the secondary phase, by the St. Louis Cardinals. Again, he declined to sign, saying they were not offering him the money he wanted or thought he was worth.

He returned to Gulf Coast Junior College, where he went 9-2 with a 0.84 ERA.9 The Commodores were 25-12 in manager Bill Frazier’s first of 24 seasons at GCJC.10

On June 5, 1969, Baltimore selected Garland with the fifth overall pick in the June secondary draft. This time he signed a deal that was reported to include a $30,000 bonus.11

The road to the big leagues began with the Miami Marlins of the Class A Florida State League. After two undistinguished seasons, Garland had a breakout year with Dallas-Fort Worth of the Class AA Dixie Association.12 He was the league’s top pitcher in 1971, going 19-5 with a 1.71 ERA. He had tremendous control, striking out 154 batters while walking 50. Garland also posted 20 complete games in 25 starts.

Promoted to Rochester of the AAA International League for the IL playoffs, he pitched Game Two of the championship series against Tidewater, going 8 2/3 innings and striking out seven in a no-decision effort. Rochester won the International League title.

Against Denver in the Little World Series, Garland started Game Two, pitched seven strong innings and drove in a run in the Red Wings’ 6-4 win. Rochester topped Denver in seven games.

The Orioles had remarkably strong starting pitching in those years. The three-time American League champions boasted a major-league record four starters with 20 or more wins in 1971: Mike Cuellar (20-9), Pat Dobson (20-8), Dave McNally (21-5), and Jim Palmer (20-9). Although Garland was just a level below the major leagues at Rochester in 1972, even if he had a season like the one he had in Dallas in 1971, he might not have been able to join the O’s.

As it developed, Garland found the going tougher against Class AAA. He did not win his sixth game until August 18, when he shut out Syracuse, 3-0.13 Garland ended the season with a 7-9 record and a 3.79 ERA. He led the team in strikeouts with 136 and walked 49.

While he was pitching for the Red Wings, Garland was dating Mary Sciarabba. They had met the previous season and continued their relationship when Garland returned to Rochester for the 1972 season. Mary and Wayne married on February 3, 1973.

Despite his lackluster season at Rochester, Garland could see a sliver of light in his future in Baltimore. The Orioles dealt Dobson and pitching prospect Roric Harrison to Atlanta as part of a six-player deal on November 30, 1972. However, with the new position of the designated hitter beginning in 1973, the extra position might be a cause to sacrifice another player, perhaps a pitcher. Also, even by the standards of the day, Orioles manager Earl Weaver used relatively small pitching staffs.

Garland returned to Rochester in 1973 and improved somewhat, going 10-11 with a 3.57 ERA. He once again led the team in strikeouts (141) and complete games (11). His performance was good enough to earn a call-up to the Orioles. In his big-league debut on September 13, 1973, against Milwaukee at Memorial Stadium, he pitched three innings of relief, giving up two earned runs and receiving no decision. Garland made his first start in the majors on September 27 against Detroit. He took the loss after pitching seven innings and surrendering four runs, three earned.

Garland went to spring training with Baltimore in 1974 but was optioned back to Rochester at the end of camp. He opened the season by hurling a no-hitter on April 20 at Charleston, striking out five and walking one as the Red Wings topped the Charlies, 5-0. “Wayne is primarily a fast ball pitcher,” said Charleston center fielder Dave Augustine. “Today he had a good fast ball, but his breaking stuff was the best I’ve ever seen him throw. When his breaking ball is that good, it makes his fast ball look really good. He didn’t give anybody anything today. I’ve got to give him credit.”14

While Augustine was heaping praise on his worthy opponent, one of Garland’s Red Wing teammates talked about the pressure involved in playing the final inning of a no-hitter. “You have no idea how much pressure there is with it being opening day and a pitcher throwing a no-hitter,” said Rochester third baseman Doug DeCinces. “Every batter in the last inning was a guy who could bunt, but I knew they could hit the ball by me too. I didn’t know what to do.

“[Charleston shortstop] Mario Mendoza topped a dribbler down the line [in the eighth inning.] I thought it was going foul, but it kicked back in fair. I knew he could run, so I just threw the ball as hard as I could and got him out. I would have looked kind of stupid if I let it roll and it hit the bag.”15

Lefty Don Hood was used mostly as a reliever by Earl Weaver in 1974. He was set to make his first start of the season in the second game of a doubleheader against New York on May 26, 1974. But Hood was scratched from the assignment and Baltimore recalled Garland from Rochester to take his place. Pitching in relief of starter Doyle Alexander in the nightcap on May 26, he hurled one-third of an inning and surrendered two earned runs.

Garland made six starts for the Orioles in 1974 but worked mostly out of the bullpen, going 5-5 with a 2.97 ERA in 20 games overall. On July 3 at Fenway Park, he pitched 6 1/3 innings, striking out two, walking two, and giving up three earned runs in the O’s 6-4 win. “He did a great job tonight,” said Baltimore pitching coach George Bamberger. “His ball was really sinking. I kept asking him each inning how much longer he could go and he kept saying ‘Let me try one more.’”16

Garland’s best pitching performance of 1974 came on July 15 at Memorial Stadium. The World Champion Oakland Athletics were in town for the beginning of a three-game series. In the opener, the O’s led, 4-1, headed into the top of the ninth inning. Garland was pitching a no-hitter against the champs. Oakland had picked up an unearned run in the top of the second without the benefit of a hit.

But the roof caved in after Garland yielded a leadoff single to Dick Green in the ninth. He got just one out; Oakland went on to score five and beat the Orioles, 6-4. Though Garland allowed just two earned runs, he took the loss.

Garland was much more effective as a reliever that year: 3-1 with a save and an ERA of 1.55 in relief. The Orioles won the American League East Division for the fifth time in six seasons and faced Oakland in the ALCS. The A’s disposed of the Orioles in four games. Garland pitched two-thirds of an inning in relief of McNally in Game Two. That was to be the only postseason appearance of his career.

On December 4, 1974, McNally was part of a five-player swap with Montreal. Right-handed pitcher Mike Torrez and outfielder Ken Singleton. Palmer, Torrez, Cuellar and left-hander Ross Grimsley, who won 18 games in 1974, made up the Orioles’ starting rotation. Doyle Alexander filled in when Weaver needed him. In 29 appearances, Garland (2-5, 3.71 ERA), made only one start. Baltimore (90-69) finished 4½ games behind Boston.

Garland was not happy, and much of it had to do with Weaver and the way he was being used. On June 30, 1975, the Orioles recalled pitcher Paul Mitchell from Rochester. Mitchell was given several starts and Garland remained in the bullpen, becoming especially unhappy.

Garland asked the Orioles for a raise from his current salary of $23,000 to $25,000 for the 1976 season. Baltimore went in the opposite direction, cutting his salary down to $19,000. With teams looking towards the beginning of free agency, the Orioles front office was forcing Garland out the door. On the advice of his agent, Jerry Kapstein, Garland played out his option during the 1976 season,

Before that season began, there was more shuffling within the Orioles’ rotation. Ken Holtzman and Reggie Jackson came over in a trade with Oakland, sending Torrez, Mitchell and outfielder Don Baylor to the west coast. As in 1975, Garland began the season pitching in relief. Through the first six weeks of the season, he posted a record of 3-0 with a 1.95 ERA. He made his first start against Boston on May 28 at Fenway Park, pitching the O’s to a 4-1 victory.

Although Holtzman was 5-4 for Baltimore in the first part of the season, he and Alexander were part of a 10-player trade with the Yankees on June 15, 1976. Among the players coming to the Orioles were three pitchers: Scott McGregor, Rudy May, and Tippy Martinez. May was inserted into the starting rotation with Palmer, Grimsley, and Garland, who was there to stay for the remainder of the season. He was impressive, winning seven of eight starts between June 17 and July 20, including four complete games.

At the end of July, his record stood at 10-2. The Orioles made an increased salary offer of $40,000. But on advice from Kapstein, Garland declined. His wife Mary begged him to sign the contract, as bills kept coming in. She was also worried that Wayne might get hurt and then they would wave goodbye to the cash. Yet despite her entreaties, Garland did not need much incentive not to sign. He and Weaver did not get along, and he favored Joe Altobelli to take Weaver’s place. “I’m not going to make the decision to sign just because Altobelli might be here,” said Garland. “But if he were, it would make me want to stay here much more than with him (Weaver) here.”17

Garland closed the season winning five of six games to end the season with a 20-7 record. His 20th win came against Milwaukee in the first game of a doubleheader on September 28 at Memorial Stadium, an 11-inning complete game won by Bobby Grich’s two-run homer.. “Winning 20 wasn’t possible without the support of 24 other guys, especially the defense,” said Garland. “I don’t think I would’ve won 20 with another team.”18

Even throughout this breakthrough year, Garland remained unhappy in Baltimore. As Weaver later remarked, “You know what his nickname was with us? We called him ‘Grumpy.’ This guy was a big grouch when he won 20 games for me in 1976. I had to run him to the mound four times in September, so he’d win that twentieth game, and he bitched about it the whole time. And I found it better not to listen.”19

The free agent market awaited many players after the 1976 season. The Orioles lost Jackson, Grich (another Kapstein client), and Garland to other clubs. Cleveland had finished 81-78 in 1976, the franchise’s first winning season since 1968. The Tribe was looking to improve its pitching staff. Dobson (16-12, 3.48 ERA), Dennis Eckersley (13-12, 3.43 ERA) and Jim Bibby (13-7, 3.20 ERA) were the workhorses. They had high hopes for young Rick Waits (7-9, 4.00 ERA) to step up in 1977 and have a solid season. The back end of the bullpen was anchored by right-hander Jim Kern (15 saves) and southpaw Dave LaRoche (21 saves).

Cleveland was looking for an established arm to take the lead of the staff. They set their sights on Cincinnati’s Don Gullett and Garland. Gullett signed with the Yankees on November 18. So the very next day, the Tribe settled on Garland, wanting to make a big splash in free agency. Indeed, the front office launched a “cannonball,” signing Garland to a 10-year, $2.3 million pact.

Garland said all the right things about how happy he was to be with the Indians’ organization, how talented the club was, and how there was no reason that they could not compete for the AL East championship. Kapstein and Garland parlayed a breakout season in his option year. “It’s been a tough life for 12 months,” said Garland. “It was that long ago we decided to take the chance and play out the season to become a free agent.”20

The Indians’ newest acquisition could not resist the urge to take a parting shot at his former manager. “I could never talk to Weaver man-to-man,” said Garland. “He ignored me as a pitcher and a person. I’m glad to get away from him, but that has no bearing on my signing with another team.

“I was 2-5 and doing nothing in the bull pen when I decided to take the chance. Then I became a starter, worked regularly, and got confidence and the rest is history. Like the other players, I was curious what I would get. I had no idea it would be this.”21

Cleveland general manager Phil Seghi was asked why he had favored Garland over Gullett (despite the Yankees’ prior signing). “Garland, because Gullett has so many injury problems,” said Seghi.22 He was right about Gullett — but events proved that Garland couldn’t stay healthy either.

Garland was the source of some good-natured ribbing from his new teammates. Don Hood (who was traded from Baltimore to Cleveland in 1975) accidentally picked up Garland’s equipment bag. “I see you’ve already got Hood carrying your money bags,” said Indians manager Frank Robinson.23

The Indians sported a 3-1 record as Garland made his debut in their home opener on April 16 before 51,165 fans at Cleveland Stadium. In a coincidence with his contract figure, Garland was issued uniform number 23 when Dave LaRoche was traded to California on May 11. Garland eagerly claimed his uniform number 17, which he’d worn in Baltimore. Unfortunately, his start that day was a harbinger of things to come in his time in Cleveland. The Tribe’s million-dollar pitcher gave up two runs in the first inning and two more in the fifth before exiting the game after 4 2/3 innings. “Wayne Garland, the $2.3 million pitcher, offered little more than a nickel and dime showing before being dispatched to the showers, or the counting room, by Manager Frank Robinson,” wrote Tom Melody of the Akron Beacon Journal. 24

Garland posted a 13-19 record with a 3.60 ERA for the Indians in 1977. He was tied for the league lead in losses with Oakland’s Vida Blue and Rick Langford. Garland and Blue also tied for second in the league with 38 starts each. Garland closed the season winning three of four games. “I think I pitched better in 1977 than I did in 1976,” he said. “The difference was I was pitching for a second-division team instead of a first-division team.”25 The Indians (71-90) finished in fifth place in the AL East.

It was also revealed that he had pitched with a sore right arm for most of the season. eddespite receiving a cortisone shot in spring training.

On April 29, 1978, Garland (2-2, 7.07 ERA) was making his sixth start of the season at Oakland. He was removed from the game in the second inning and was diagnosed with a torn rotator cuff. Surgery was performed on May 5, and he was lost for the 1978 season. “I feel like I got hit in the solar plexus,” said Seghi. “This is a severe blow. They won’t know until they go in whether he can ever pitch again.”26

The surgery was performed by Dr. Frank Jobe and was deemed a success. Garland did return to pitch for the Indians in 1979. However, he went on the disabled list with torn adhesions, a side effect of his surgery. Although Garland was throwing well in his rehab, the Cleveland front office was cautious about reactivating him. He was 3-8 with a 5.31 ERA when he went on the DL again. Garland returned in late August and pitched in five games, three in relief. His season record was 4-10, with a 5.23 ERA.

In his quest to regain success, Garland turned back to the knuckleball in 1980. He’d used it some in 1975 but discarded it the following year.27 In a game against Toronto on May 4, he threw it for about 40% of his pitches in four innings of relief. It was reasonably effective.28

Yet if there was a game in Garland’s time in Cleveland that gave fans a glimpse of what was anticipated when he signed his $2.3 million contract, it was on July 3, 1980. Cleveland Stadium was packed with 73,096 fans who turned out for a holiday fireworks extravaganza. The Yankees were in town and Garland was matched against New York’s Tom Underwood. Garland gave the fans something to cheer besides a fireworks show as he pitched a complete-game, two-hit, 7-0 victory. “It was a pleasure to play behind him tonight,” said Indians first baseman Mike Hargrove. “The lefties were trying to pull him to death all night. He’s an outstanding person who’s got the same competitive drive Gaylord Perry has. And he knows how to pitch.”29

Alas, Garland’s relationships with Seghi and club president Gabe Paul soured. “They didn’t believe my arm was as bad as it was,” said Garland. “A lot of things happened that never came out [in the media]. They were always telling me, ‘We’re paying you a helluva lot of money and it’s time you start earning it.’”30

It was also noteworthy that Garland was the Indians’ player representative. The threat of a players’ strike had settled over baseball beginning in 1980 and carried over to the 1981 season. The MLB players union disagreed with management over free-agent compensation. The players walked out on June 12, 1981.

While the strike was in progress, Garland took a job in a gas station. A photo of him pumping gas into a car made the papers coast-to-coast. “I wasn’t ashamed to be seen pumping gas and wiping windshields,”31 he said.

An agreement was reached on July 31. The shortened 1981 season was Garland’s last in the big leagues. He compiled a career record of 55-66 with a 3.89 ERA. In 1,040 innings pitched, he totaled 450 strikeouts and 328 walks.

The Indians released Garland in January 1982. He gave it a last shot with the Yankees organization, joining their Double-A club in his hometown, Nashville. The club president and GM, Larry Schmittou, had been Garland’s coach in youth ball back in the ’60s.32 The signing gave Wayne another chance to pitch in front of his parents.33 He worked on his knuckleball with Hoyt Wilhelm but did not find success.34 In six starts, Garland went 1-3, with a 7.48 ERA.

In late July, about a month after Nashville released him, Garland joined the Milwaukee Brewers organization as a pitching coach in the Appalachian League (rookie ball).35 His coaching career had various stops, including a return to the Nashville Sounds, then a Reds affiliate, in 1987 and 1988. He served as Nashville’s interim manager in 1988 after George Scherger resigned. Garland was a pitching coach in the Pittsburgh Pirates organization as late as 1995.

Wayne and Mary divorced in 1987. They had three children, sons Brett and Todd and daughter Ashley. Garland remarried in 1991; he and his wife Kathie live in Las Vegas.

In retirement, Garland was involved in several other jobs and business ventures. He invested in the oil business and he also owned an indoor batting cage. He worked for Walmart and a freight company, and filed for personal bankruptcy in 1988.36

His health deteriorated. He had a second surgery on his rotator cuff in 1990 and later had multiple operations on his back. “After my first back surgery [1995], the doctor told me I had the back of a 75-year old man,” said Garland. “He was probably right. And now, when I’m on my feet for 15 or 20 minutes, my right leg goes numb and I have to sit down. I can’t do much of anything.”37 As a result, he is on total disability.

The subject of the lucrative contract is brought up constantly to Garland. He didn’t ask for the money, and the shoulder injuries were not his fault. If anything, his competitive drive got the best of him — he returned too quickly from the 1978 rotator cuff surgery. His career in Cleveland was harder on this man than it was on anyone else, whether anyone believes it or not.

For Garland it was simple. He just wanted to pitch. “When I stepped over the white line,” he said, “I gave 100 per cent every time.”38

Last revised: August 18, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Bob Dolgan, “Of riches and pitches,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 20, 1997: 1-C.

2 Jimmy Davy, “Little Changes for Garland’s Parents,” The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), May 23, 1982: 39.

3 “William ‘Bill’ Conrad Garland,’ obituary, May 1, 2020, West Harpeth Funeral Home and Crematory (https://www.westharpethfh.com/obit/william-bill-conrad-garland/)

4 Bob Teitlebaum, “Cohn Clinches NIL Baseball Crown”, The Tennessean, May 23, 1968: 38.

5 Teitlebaum, “Cohn Clinches NIL Baseball Crown.”

6 Bob Teitlebaum, “Post 5’s Garland Hurls Perfect Game, 2-0,” The Tennessean, August 2, 1968: 36.

7 “Garland’s No-Hitter Leads Post 5, 3-0,” The Tennessean, August 28, 1968: 29.

8 “Garland, McLean Named All World,” The Tennessean, August 30, 1968:

9 “Garland Inks for $30,000,” Panama City News-Herald, July 9, 1969: 9.

10 “Gulf Coast Men’s Baseball Record Book”, May 20, 2019. Accessed April 21, 2020 http://www.gcathletics.com/baseball/documents/2018-19/1960-2019%20Baseball%20Records%20Revised.pdf

11 “Garland Inks for $30,000.”

12 The Dixie Association was in existence for only the 1971 season. The Texas League and the Southern League each lost a league member after the 1970 season. Both leagues combined to form the Dixie League for one season. In 1972, both leagues returned to their original organization. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Dixie_Association Accessed April 21, 2020.

13 Bob Matthews, “Wings Sweep Pair, Hold 4th by 1 Game,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 19, 1972: D-1.

14 Larry Bump, “’Wings Garland pitches no-hitter,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 21, 1974: D-1.

15 Larry Bump, “Opposing fans hail happy hero,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 21, 1974: D-1.

16 “Birds sweep twin-bill from Bosox, 9-3, 6-4,” Baltimore Sun, July 4, 1974: C11.

17 Jim Henneman, “’Tampering’ Screams Hank at Oriole Rivals,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1976: 3.

18 Lou Hatter, “Birds top Brewers twice; Garland wins 20th,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1976: C5.

19 Terry Pluto, The Curse of Rocky Colavito: A Loving Look at a Thirty Year Slump, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 227.

20 Bob Sudyk, “Will Garland’s salary create problems?” Cleveland Press, November 20, 1976: C-1.

21 Sudyk, “Will Garland’s salary create problems?”

22 Hal Lebovitz, “Hal Asks,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 28, 1976: 3-7.

23 Dolgan, “Of Riches and Pitches.”

24 Tom Melody, “Situation still ‘normal’ for Tribe,” Akron Beacon Journal, April 17, 1977: D-1.

25 Dolgan, “Of Riches and Pitches.”

26 Dan Coughlin, “Tribe Loses Garland”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 2, 1977: 1-A.

27 “Garland’s Knuckleball Saved As Ace-In-Hole,” York (Pennsylvania) Daily Record, June 29, 1976: 13.

28 Richard A. Johnson, The Knuckleball Club, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2016): 184.

29 Bob Sudyk, “It was a gem,” Cleveland Press, July 4, 1980: C-1.

30 Russell Schneider, Whatever Happened to Super Joe? Catching Up With 45 Good Old Guys from the Bad Old Days of the Cleveland Indians (Cleveland: Gray & Company, Publishers, 2006), 107.

31 Dolgan, “Of Riches and Pitches.”

32 Ira Berkow, “Garland Eyes the Road Back,” New York Times, May 10, 1982: C9.

33 Davy, “Little Changes for Garland’s Parents.”

34 Mike Tully, “Wayne Garland Recalls His Historic Contract,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1988.

35 “Career Change: Wayne Garland Hired as Coach,” The Tennessean, July 27, 1982: 42.

36 Leigh Montville, “The First to Be Free.” Sports Illustrated, April 16, 1990: 140.

37 Schneider, Whatever Happened to Super Joe? 105.

38 Tully, “Wayne Garland Recalls His Historic Contract.”

Full Name

Marcus Wayne Garland

Born

October 26, 1950 at Nashville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.