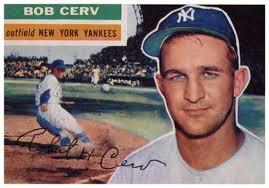

Bob Cerv

Bob Cerv survived kamikaze attacks in World War II and put all 10 of his children through college. In between, he was a three-time New York Yankee. The Yankees signed him, traded him, brought him back, let him go, and brought him back again.

Bob Cerv survived kamikaze attacks in World War II and put all 10 of his children through college. In between, he was a three-time New York Yankee. The Yankees signed him, traded him, brought him back, let him go, and brought him back again.

His claim to Yankee fame came in 1961, when he shared an apartment with Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle while they chased Babe Ruth’s home run record. The trio surely set a record for most homers under one roof: Maris hit 61, Mantle 54, and Cerv 6.

Cerv got into three World Series, but he was a small cog in the powerful Yankee machine of the 1950s and early 1960s, as a pinch-hitter and platoon outfielder. Like his contemporaries, he was a prisoner of baseball’s reserve clause. When he finally got a chance to play regularly in his 30s, he set the Kansas City Athletics home run record.

Robert Henry Cerv was born in Weston, Nebraska, on May 5, 1925, the only son of Henry Cerv, a truck driver, and the former Henrietta Staska. He had three younger sisters. The family name, Bohemian in origin, is properly pronounced “Cherf,” but was Americanized to “Serve.”

Bob’s father and an uncle played ball for the town team. When the boy visited his grandfather’s farm outside Weston, he didn’t want to pick up the walnuts that fell from a tree until his grandfather made him a bat. “After that,” Cerv recalled, “there never was a walnut on the ground. Hitting walnuts. I’d hit them into a little creek out there.” His grandfather attached a baseball to a chain hanging from a cottonwood tree. “I’d hit that thing, and it would go out there and come back. I’d hit that thing by the hours.”1

When Bob was 11 or 12, he rode with his father to New York, delivering eggs and milk in a refrigerated truck, and they took in some games at Yankee Stadium. After watching Lou Gehrig hit two home runs, he told his dad, “I’m going to play for the Yankees someday.”2

The local high school had no baseball team, but Bob was a star in basketball. He didn’t go out for football because he didn’t want to risk an injury that would interfere with his baseball dream. He played American Legion ball as a catcher and outfielder, once meeting a team from St. Louis whose star was Yogi Berra. Bob was still in high school when he began playing against adults in the Pioneer Night League, a semipro circuit of small Nebraska towns.

The 18-year-old joined the navy after graduation. Assigned as a radarman aboard the destroyer Claxton in the Pacific, he escaped injury in several kamikaze attacks during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval engagement of the war. One of the suicide attacks, off the Philippines on November 1, 1944, killed five Claxton sailors. When the ship returned home, President Truman presented the destroyer squadron with Presidential Unit Citations and shook the Nebraska boy’s hand.3

Cerv enrolled at the University of Nebraska in 1946 on the G.I. Bill. In his freshman year he met Phyllis Pelton, and married her while still in school on June 5, 1948. According to the university, he is the only Cornhusker to earn four letters each in basketball and baseball. His teams won or shared two Big 7 conference titles in each sport. After batting .444 and slugging .878 in his senior season, he was chosen in a coaches’ poll as Nebraska’s first baseball All-American.4

By the time he graduated, Bob and Phyllis already had two daughters. At 25, he signed with the Yankees for a $5,500 bonus and began his pro career at the top level of the minors, Triple-A Kansas City, in 1950. A right-handed batter, 6 feet tall and around 200 pounds, he played center field and hit .304 in 94 games.

In July 1951 Cerv was leading the American Association in home runs, RBIs, and batting average when the Yankees called him up and demoted their slumping rookie phenom, Mickey Mantle, to Kansas City. Cerv took Mantle’s place in right field, but was benched after managing only one single in his first 11 plate appearances. Less than a month later, he and Mantle swapped uniforms again. Back in Triple A, Cerv’s season ended when he separated his shoulder on August 31.

His eye-catching stats in Kansas City — 22 doubles, 21 triples, 28 homers, and a league-leading .344 batting average — put him in the Yankees’ plans for 1952. Even with Joe DiMaggio retired and Mantle limping from a knee injury suffered in the World Series, the Bronx Bombers, as usual, had no shortage of talent. Gene Woodling and Hank Bauer locked down the outfield corners. Cerv competed for the center-field job with bonus baby Jackie Jensen, veteran Johnny Hopp, and rookie Archie Wilson.

Cerv hit two long home runs in spring training, and manager Casey Stengel commented, “He has power, he can run, he will make it.”5 But Jensen won the starting nod in center on Opening Day, with Mantle in right and Bauer and Woodling platooning in left.

In his first start, in the season’s ninth game, Cerv struck out three times and left 10 runners on base. Jensen wasn’t doing much better; he was 2-for-23 when the Yankees traded him to Washington for outfielder Irv Noren on May 3. A week later Cerv crashed into Yankee Stadium’s outfield wall and knocked himself cold. That same day Mantle moved to center.

That left Cerv as the fifth outfielder, pinch-hitting and platooning occasionally with Woodling. He was batting .241 in 56 games when he was sent back to Kansas City in July. His Yankee teammates voted him a $3,000 partial World Series share, and he picked up another $1,200 when Kansas City won the Junior World Series.

In 1953 another right-handed power hitter, Bill Renna, beat him out for the fifth outfield spot, and Cerv returned to Triple A. But that used up his last minor-league option; the next spring the Yankees had to keep him or lose him, because several other teams had tried to get him in trades.

Renna was traded before the 1954 season, and Cerv spent the next three years on the Yankees’ bench. After Woodling was dealt away, Noren became the primary left fielder in 1955. Elston Howard, a right-handed hitter like Cerv, won the job in 1956 and ’57. Cerv never started more than 30 games in the outfield. Stengel evidently thought his arm was inadequate for Yankee Stadium’s huge left- and left-center pasture.

It’s unlikely that Cerv ever talked to the manager about playing time, because that wasn’t Stengel’s way. “No explanation. No nothing,” second baseman Jerry Coleman said. “He never called anyone into the office and said, ‘I’m not going to do this because of this.’ He did it.” Coleman said Stengel spoke five words to him in nine years.6

Cerv gave the club a potent bat off the bench, racking up on-base plus slugging percentages of .800, .952, and .926. In his first World Series in 1955, he replaced the injured Mantle in center in four of the seven games. He managed only two hits in the Series, but one was a pinch home run in Game Five.

Late in the 1956 season, Stengel told him, “Nobody knows this, but one of us has just been traded to Kansas City.”7 This story has often been debunked because the record shows that Cerv was not sold to the Athletics until after the season, but he said it was true.8 It appears that the Yankees secretly promised him to Kansas City as part of their deal to acquire Enos Slaughter in an August waiver transaction. That violated baseball rules; a waiver deal was supposed to be a straight cash sale.

“I was tickled to death,” Cerv said years later, “because I could play every day. And I proved to them that I could play every day.”9 He was liberated from the bench, but he was leaving behind any hope of another World Series check, because the Athletics were a tail-end team. His wife, Phyllis, was tickled, too. She liked Kansas City, and it was closer to home in Nebraska. Cerv moved his family, now numbering six children with a seventh on the way, to his new baseball home.

He was surrounded by familiar faces #— about half the Athletics had come from the Yankees in the incestuous relationship between the clubs — but his first year was a disappointment. Slowed by an ankle injury and admittedly overweight at nearly 240 pounds, he started only 77 games with a batting line of .272/.312/.420 and 11 home runs. It didn’t make much difference; the A’s finished seventh.

During the offseason, Kansas City writer Ernest Mehl said Cerv “realizes it is now or never as far as his baseball career is concerned.”10 He reported to spring training nearly 20 pounds lighter and started the 1958 season on a tear. In the first three games he rapped out two home runs and three doubles, and drove in nine.

By May 17 he was leading the league with 11 homers and 30 RBIs. That day, trying to score from second on a squeeze bunt, he crashed into Detroit catcher Red Wilson, a former Big 10 linebacker. Wilson said Cerv “looked like a mad rhino” charging toward the plate.11 Cerv was out and down, with a broken jaw.

He missed only three games, then returned to the lineup with his jaws wired shut. For nearly four weeks he played every game, although every swing, throw, and slide brought intense pain. He had trouble breathing, so the trainer treated him with oxygen in the dugout. The first time he took a whiff, he hit a home run. His teammates began demanding oxygen before their at-bats.

Subsisting on a liquid diet — mostly pureed steak and potatoes — Cerv lost 30 points off his batting average, but hit six home runs in 28 games and was still leading the league when the wires came off. His jaws were so sore he couldn’t chew a steak for another two weeks.12

After he recovered, Cerv broke a toe and sprained a knee, and was hit in the arm by a Ryne Duren fastball, but he shrugged off those inconveniences. Players, managers, and coaches voted him the starting left fielder in the All-Star Game. On July 22 the Athletics staged Bob Cerv Night at the ballpark. Former President Truman and the governors of Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska turned out to honor him. Cerv received more than $6,000 in cash as well as a slew of gifts.13

Truman claimed to remember their wartime handshake, and invited Cerv to visit him at his home in Independence, Missouri. Cerv stopped by several times to chat.

He finished in the American League’s top five with 93 runs, 38 homers, 104 RBIs, a .963 OPS, and 6.3 wins above replacement (WAR). His 38 home runs are still the most by any player for either of Kansas City’s two big league franchises as of 2017. He was fourth in the Most Valuable Player voting. It was a triumphant season, but only reminded the 33-year-old of what might have been.

He couldn’t do it again. Injuries to his back, thumb, and knee limited Cerv to 125 games in 1959, with 20 homers and an .812 OPS. After the season he was invited to compete on the syndicated TV series Home Run Derby. At the filming in Los Angeles’s Wrigley Field, he outslugged Frank Robinson to win $2,000, then lost to Bob Allison, taking home a $1,000 consolation prize — not as good as a World Series share, but a useful addition to his $30,000 salary.

In May 1960 Kansas City traded him back to the Yankees for Andy Carey, who was once the club’s regular third baseman but had fallen out of favor with Stengel. After dropping to third place in 1959, New York was fighting the young Baltimore Orioles for the pennant. Cerv went into the lineup in left field, joining Mantle and his Kansas City roommate, Maris, in the outfield. The Athletics had traded Maris to the Yankees during the offseason.

Three days after Cerv arrived, the two former A’s returned to Kansas City for the first time. Fans welcomed them like old friends, but they abused the local hospitality when they both hit home runs.

Cerv moved with Maris into an apartment near the Forest Hills tennis center in Queens. They left their families at home during the season. “We were a lot alike,” Cerv said, “just small-town Midwestern guys who did our jobs and let others make the noise.”14 His job soon became part-time left fielder. Slowed by a bad knee, he couldn’t cover the spacious Yankee Stadium outfield. He started 65 games and went to bat 249 times, the most of his career in pinstripes. The results were better than average: eight homers and a .771 OPS.

Cerv started three World Series games against Pittsburgh and batted .357. After the Series the Yankees left the 35-year-old unprotected in the expansion draft that stocked two new teams. The Los Angeles Angels chose him along with other well-known veterans including Ted Kluszewski, Eddie Yost, and Ned Garver.

In the first inning of the first game in Angels history, at Baltimore, Kluszewski and Cerv hit consecutive home runs. Klu added another homer as the castoff lineup beat the Orioles, 7-2. The Angels played their home games at Wrigley Field, the hitter-friendly site of Home Run Derby, but Cerv connected only once in 10 games there.

The 1961 season was less than a month old when the Yankees brought him back in a five-player deal that sent reliever Ryne Duren and a young slugger, Lee Thomas, to L.A. Cerv was primarily a pinch-hitter in New York, with a front-row seat for the home run derby featuring Mantle and Maris.

When Maris suggested that Mantle move in with them, Cerv resisted. He knew the superstar deserved his reputation for drinking and womanizing. “I didn’t know whether I wanted him or not, ’cause I knew what he did…. But I said, ‘These are the rules. If you break them, you’re outta here — no partying, no girls.’”15

As Mantle and Maris chased Ruth, the apartment became their refuge from pandemonium. “I was the father figure,” Cerv said. “I did all the shopping and the cooking. I ran the place…. We spent a lot of nights just sitting in the living room watching some television comedy and sipping a beer.”16 Sportswriters invented a feud between the “M&M boys,” not knowing they were housemates.

Mantle stuck with the quiet domestic life until around Labor Day. “Then he said, ‘I’ve had enough of this. I gotta have some good times,’” Cerv recalled.17 Soon after he moved out, the Mick caught what was described as a cold and got a shot from a shady doctor. Before the end of the season he wound up in Lenox Hill Hospital with complications from the botched injection. Cerv was already in the same hospital after knee surgery when Maris hit number 61.

Forty years later comic Billy Crystal directed a television movie, 61*, about the home-run chase. “My wife says I’m better-looking than the guy who played me,” Cerv told an interviewer. The only one of the housemates still living, he judged the film to be about 70 percent accurate. One scene showed him and Mantle watching on TV in a hospital room as Maris broke the record. Cerv said that happened only in the filmmaker’s imagination.18

More knee problems sidelined Cerv in early 1962. On June 26 the Yankees sold him to the expansion Houston Colt .45s, but Houston released him a month later. He tried out with the Mets the next spring, but failed to make the team.

That summer he managed Bob Cerv’s Home Plate Restaurant in Kansas City’s Berkshire Hotel, where some of the Athletics players lived. He left professional baseball, but never left the game. In 1966 he began a 10-year stint as head coach at John F. Kennedy College in Wahoo, Nebraska, then moved to Sioux Empire, a junior college in Hawarden, Iowa.

He enjoyed his greatest success as manager of the BeeJays, a semipro team in Liberal, Kansas, for 10 summers between 1970 and 1982. He led the team to the finals of the National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita three times. Cerv’s Beejays won the national championship in 1979 behind the pitching of Mike Moore of Oral Roberts University, who went on to a 14-year major league career. Others who played for him included Ron Guidry, Mike Hargrove, Rick Honeycutt, and Doug Drabek.

“I got all 10 of my kids through college,” Cerv said. “That’s my greatest accomplishment.”19 In retirement he returned to Yankee Stadium for Old Timers Days and picked up some extra money at autograph shows. Sometime after Phyllis died in 2005, he moved to a nursing home in Blair, Nebraska. Several of his seven daughters and three sons lived nearby — not to mention 32 grandchildren and 20 great-grandchildren.

For as long as he was able, he went with his son Joe to a Royals game every time the Yankees came to town. Although he played fewer than half of his 829 big-league games in pinstripes, another son, John, said, “He was proud to be a Yankee. That’s who he felt he was.”20 Bob explained, “You just know when you put those pinstripes on that you’re carrying that tradition forward. There’s nothing like it, and it really stays with you for all your life.”21

Cerv died on April 6, 2017. The University of Nebraska baseball team went ahead with plans to give away Bob Cerv bobbleheads on May 5, which would have been his 92nd birthday.

Photo credits

The Topps Company, Andy Wenstrand/Nebraska Athletics

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Larry Moffi, This Side of Cooperstown (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1996), 195.

2 Ibid., 196.

3 “History of the USS Claxton, DD571,” https://sites.google.com/site/ussclaxton/home/history-of-the-uss-claxton-dd571, accessed July 7, 2017.

4 Clark Grell, “Bob Cerv, one of the Nebraska baseball greats, dies at 91,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal Star, April 7, 2017. http://journalstar.com/sports/huskers/baseball/bob-cerv-one-of-the-nebraska-baseball-greats-dies-at/article_efafdb84-32b9-5290-a41f-4984f4845b40.html, accessed June 24, 2017.

5 Dan Daniel, “Bomber Garden Will Be Best in League, Boasts Ol’ Case,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1952: 14.

6 Jane Leavy, The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood (New York: Harper, 2010), 120.

7 Robert Creamer, Stengel: His Life and Times (repr. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 262.

8 Moffi, 201.

9 Rich Kaipust, “Nebraska native, former Husker and MLB star Bob Cerv lived lucky life; in prime he was All-Star in Kansas City,” Omaha World Herald, April 7, 2017. http://www.omaha.com/sports/local-sports/nebraska-native-former-husker-and-mlb-star-bob-cerv-lived/article_2999da36-1baf-11e7-895e-b7216c4830f5.html.

10 Ernest Mehl, “Johnson of A’s to Mark Time in Trade Mart,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1957: 8.

11 “Cerv Looked Like Mad Rhino Barging Into Plate — Wilson,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1958: 24.

12 Bob Cerv as told to Al Hirshberg, “I Played Without Eating,” Saturday Evening Post, July 19, 1958: 23, 56, 58.

13 “Wild Response at Cerv Night,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, July 23, 1958: 4.

14 Maury Allen, Yankees, Where Have You Gone? (Kingston, New York: Sports Publishing, 2004), 20.

15 Leavy, 220.

16 Allen, 20.

17 Leavy, 229.

18 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 63.

19 Allen, 18.

20 Richard Sandomir, “Bob Cerv, Three-Time Yankee and One-Time All-Star, Dies at 91,” New York Times, April 13, 2017: B13.

21 Allen, 21.

Full Name

Robert Henry Cerv

Born

May 5, 1925 at Weston, NE (USA)

Died

April 6, 2017 at Blair, NE (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.