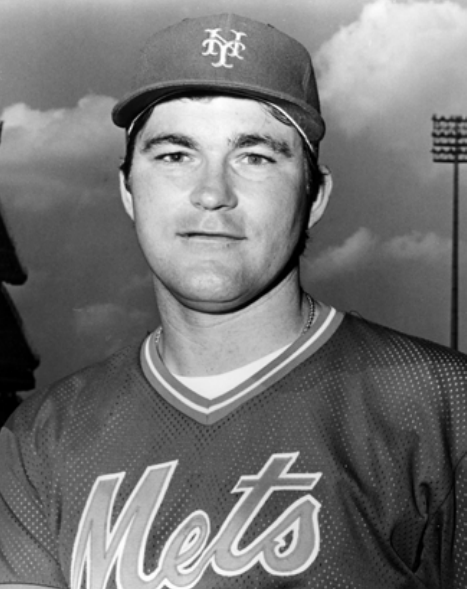

Bruce Berenyi

In the winter of 1981-1982 the Cincinnati Reds began dismantling remnants of the powerful Big Red Machine. Outfielder George Foster’s contract was scheduled to run out after the 1982 season and the slugger was rumored to be seeking a $20 million renewal. On the heels of the departures of Ken Griffey and Ray Knight, Foster was traded in February. But general manager Dick Wagner drew the line on three untouchable pitchers: future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver and two promising youngsters Mario Soto and Bruce Berenyi. The lofty company Berenyi shared wa s not undeserved. The third overall pick in the 1976 June draft (secondary phase) had shown great promise through the minors and in 27 appearances with the Reds. Wagner looked to the righty as one of the cornerstones to the rebuilding of the team.

In the winter of 1981-1982 the Cincinnati Reds began dismantling remnants of the powerful Big Red Machine. Outfielder George Foster’s contract was scheduled to run out after the 1982 season and the slugger was rumored to be seeking a $20 million renewal. On the heels of the departures of Ken Griffey and Ray Knight, Foster was traded in February. But general manager Dick Wagner drew the line on three untouchable pitchers: future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver and two promising youngsters Mario Soto and Bruce Berenyi. The lofty company Berenyi shared wa s not undeserved. The third overall pick in the 1976 June draft (secondary phase) had shown great promise through the minors and in 27 appearances with the Reds. Wagner looked to the righty as one of the cornerstones to the rebuilding of the team.

Instead hard luck and injury derailed Berenyi’s future. In 1982 he was saddled with a National League-leading 18 losses for the last-place Reds despite a respectable 3.36 ERA (league average: 3.60). Little success followed as Cincinnati, last in the league in runs scored in 1982, continued its offensive malaise. As losses mounted, the frustrated youngster petitioned for a trade. The appeal was granted and Berenyi found success with the young, emerging New York Mets. But shoulder problems developed and Berenyi was soon out of baseball. He concluded a seven-year major-league career with a pedestrian record of 44-55, 4.03 — a far cry from what was once projected.

Bruce Michael Berenyi was born on August 21, 1954, one of four children of Frank and Madeline F. (Sims) Berenyi, in Bryan, Ohio, in the state’s northwest corner. At 15 Frank had emigrated with his family from Hungary in 1938. He found early employment alongside his father in a sugar-beet refinery but, as the industry began dying out in Ohio, he settled into a long career in the motor-vehicle industry. On January 10, 1948, he married Ohio native Madeline Sims.1 They remained in Bryan until their passing in 1991 and 2008, respectively.

Their children attended Fairview High School in Sherwood, Ohio. Bruce, their second son, excelled at baseball and eventually — as an admittedly late bloomer — basketball. In the early 1970s Berenyi entered Glen Oaks Community College in Centreville, Michigan. He soon attracted attention from major-league scouts. In 1975 the Detroit Tigers selected Berenyi in the 19th round of the June amateur draft. The first Glen Oaks player ever drafted — and through 2014 the only Viking to advance to the majors — Berenyi spurned the Tigers and transferred to Truman State University in northern Missouri. The next year he rewrote the record books for the TSU Bulldogs with the most strikeouts in a single game (21), most consecutive shutout innings (30), and most innings pitched in a season (65). He was named to the 1976 Mid-America Intercollegiate Athletic Association’s All-Conference team and the NCAA Division II All-District team. These achievements earned Berenyi a first-round selection by Cincinnati in June 1976.

Berenyi spent a short time in the Northwest League followed by promotion to the Shelby (North Carolina) Reds in 1977. A pedestrian start to the season unfolded into a brilliant second half campaign (7-4, 1.80 ERA in his final 13 appearances), placing Berenyi among the league leaders in wins (10), ERA (2.30), and strikeouts (120). Success followed him into the Double-A Southern League with the Nashville Sounds in 1978. Berenyi won his first five decisions, and seven of his first eight. On May 23 he twirled a one-hitter and struck out nine in a 4-2 victory over the slugging Columbus Astros (though he did exhibit a streak of wildness with seven walks and four wild pitches). A record of 8-2, 1.99 in his first 10 appearances2 captured considerable attention. A slight second-half sag did not detour Berenyi’s steady climb in the Reds’ farm system.

At Cincinnati’s 1979 spring-training camp the Reds’ new pitching coach, Bill Fischer, enthused over his first glance at Berenyi: “[N]ow that I’ve had a chance to see [him] throw, I’m even more impressed.”3 Berenyi was assigned to Triple-A Indianapolis, where he got his first peek at what lay in store for him in Cincinnati. For the first of two consecutive years the Indians were last in the league in runs scored. The futility became blatantly clear on May 16 when Berenyi tossed a one-hitter against the Omaha Royals only to suffer a 1-0 loss. In his first nine appearances he possessed a league-leading ERA of 1.43 yet was saddled with four losses. Berenyi took matters into his own hands on June 1 in a scoreless duel against the Denver Bears, delivering the Indians’ first run with an RBI single in the eighth inning in a 2-0 win. Berenyi struck out 12 while also adding to his string of 38⅔ innings without surrendering an earned run. Even more remarkable was his dominance over the Bears that evoked comparisons to the four-man softball squad The King and His Court as the Indians’ catcher, first baseman, and second baseman accounted for nine of 12 assists, 24 of 27 putouts.

But the losses proceeded as the Indians scored more than two runs in only three of Berenyi’s first 15 starts. On June 30 he endured another heartbreaking loss, yielding just six hits and one earned run in a 2-0 loss to the Iowa Oaks. Berenyi finished with a pedestrian record of 9-9 despite a league leading 2.82 ERA. He paced the league in shutouts (3) and strikeouts (136) while disconcertingly leading in wild pitches (13) and placing second in walks (98). In a postseason poll of American Association managers Berenyi was voted runner-up to righty Dewey Robinson for the Allie Reynolds Award as the circuit’s best pitcher. Indianapolis skipper Roy Majtyka said, “[Berenyi] could be the nucleus of Cincinnati’s pitching staff in a couple of years.”4 This sentiment was echoed the following spring when pitching coach Bill Fischer predicted Berenyi as the Reds’ “sleeper” to enter the rotation.

But on the eve of the 1980 season the Reds, possessing few left-handed hurlers, chose southpaw rookie Charlie Leibrandt to proceed north while Berenyi was reassigned. The dejected Berenyi’s performance suffered considerably. On April 16 he surrendered his first home run in two years (a string of 168 innings). Over his first 48⅔ innings Berenyi yielded 38 walks and 9 wild pitches and had a 6.10 ERA. He grabbed a Houdini-like 3-1 win over the Evansville Triplets on May 28 by escaping numerous scoring opportunities after yielding 11 walks in six-plus innings. The three runs came from his first professional home run. Asked to assess the bizarre outing, Berenyi said, “I’m kinda happy. … I’m kinda embarrassed.”5

Soon Berenyi began exhibiting the type of performances to which the organization was accustomed. On June 9 he struck out six consecutive Denver batters and appeared on track to break the league record of eight before being lifted after a 67-minute rain delay. Indians manager Jim Beauchamp explained, “Very few pitchers will return with the same stuff and there is always the chance they can get stiff. I would take a loss every day of the week instead of hurting an arm like Berenyi’s.”6 As for Berenyi’s abrupt turnaround: “I convinced him that [his despondency over the spring demotion] was only hurting himself. Since then his pitching has been awesome.”7 As it turned out, Berenyi’s surge could not have been more propitious.

Since the spring Reds ace Tom Seaver had been struggling with shoulder problems that helped push his ERA over an uncharacteristic 4.00. In San Francisco on June 30 he did not make it past the fourth inning. The next day Seaver was placed on the 21-day disabled list and Berenyi was called up. On July 5 the 25-year-old made a forgettable major-league debut in Cincinnati against the Houston Astros, who jumped on him for six runs in the first inning. A more promising start occurred seven days later when Berenyi was locked in a tie against the Giants’ John Montefusco. Berenyi yielded two walks to start the sixth — nine walks total — and was lifted from the game.

Berenyi curbed his wildness on July 18, yielding just six hits and three walks in seven innings to earn his first major-league win, an 8-3 victory over the New York Mets. A similar outing on July 23 resulted in a 7-3 win over the Philadelphia Phillies. His record on the year with the Reds was 2-2 and a 7.81 ERA with 23 walks in 27⅔ innings. When Seaver came off the disabled list on August 4, Berenyi was returned to Indianapolis. Control problems continued to plague him when he surrendered a bases-loaded walk in a 1-0 loss to Evansville. He concluded his last season in the Reds farm system with league-leading marks in walks (100) and, for the second consecutive year, strikeouts (121).

Significantly, throughout Berenyi’s five years in the farm system, the organization largely ignored his periodic complaints about arm soreness. Their skepticism stemmed from Berenyi’s ability to continually deliver the ball at 90-plus miles per hour. On the few occasions when the Reds acknowledged that there was a problem they tried to work with Berenyi on his mechanics in hopes of ameliorating the soreness, while going so far as to label him a hypochondriac. Their actions would eventually exact a heavy price.

After a strong start to the 1980 campaign, lefty Charlie Leibrandt struggled in the second half. The following spring the Reds felt he needed further development in the minors, thus opening the door for Berenyi to make the team. On April 14 the confidence shown the young righty was immediately rewarded with a two-hit shutout of the San Diego Padres. Four days later Berenyi labored against the St. Louis Cardinals, then delivered a strong performance against the Astros (despite six walks) to capture his second victory. His season continued to seesaw back and forth. On May 24 he complained about the umpire “squeezing the plate”8 as he threw 15 balls in succession for five walks in a 10-3 loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers. (As he left the field after having been removed from the game, a comment directed to umpire Randy Marsh earned Berenyi an ejection.) Two weeks later, in his last appearance before the 1981 players’ strike, Berenyi twirled his second major-league shutout, a one-hit, 10-strikeout outing against the Montreal Expos, a performance that catcher Joe Nolan described as a “once-in-a-lifetime”9 gem.10

Berenyi spent the two-month strike at his parents’ home in Sherwood, Ohio. He joked that he had no problem staying in shape during the layoff because in the 1,400-population village, “there aren’t many distractions for me.”11 His conditioning paid off when the season resumed in August. In 10 appearances after the strike, Berenyi compiled a 2.64 ERA (team ERA over the same period: 3.67) in 61⅓ innings with 68 strikeouts. This stretch included two career-high 12-strikeout performances, a shutout of the Mets and a 4-2 win over the Astros in which Houston manager Bill Virdon claimed Berenyi “show[ed] us the best stuff we’ve seen all season.”12 Berenyi’s record of 9-6, 3.50 in 126 innings earned him a tie for fourth in the balloting for the National League Rookie of the Year. He was named to the NL Topps All-Rookie team. The success prompted the aforementioned “untouchable” label assigned by the Reds’ general manager.

Over the winter Berenyi often commuted 340 miles round-trip to Cincinnati for special tutoring under Coach Fischer, his fierce advocate. Fischer sought to adjust Berenyi’s release point in order to improve his control. The strategy appears to have failed as Berenyi, for the second consecutive year, placed among the league leaders in wild pitches and walks. Starting 1982 soundly (4-1, 2.93) through the end of April, he followed on May 8 in a game against the Pittsburgh Pirates abuot which The Sporting News stated that Berenyi “never was more overpowering.”13 He surrendered one “tainted”14 hit through eight innings but wound up with a no-decision when the game went into extra innings. Thereafter Berenyi struggled to get into the win column, usually had a hard time getting a win after having gone 4-1.

Despite a respectable 3.36 ERA (league average: 3.60) Berenyi was victimized by many heartbreaking losses. In two consecutive August starts he did not surrender an earned run but could not capture a win. In his final 12 appearances he was saddled with a record of 1-8 despite a solid 3.16 ERA over 79⅔ innings. (The victory was a shutout, seemingly the only way he could win a game). As the losses mounted so did Berenyi’s frustration. Through his agent, the 27-year-old requested a trade but the Reds were reluctant to part with the righty whom Philadelphia Phillies’ first baseman Pete Rose described among the league’s “fine crop of young pitchers.”15 Berenyi had the lowest home-run yield among National League starters but his run support was nonexistent. He lost four games by one run, six games by two and finished the year with a league-leading 18 losses.

He fared just slightly better in 1983. In 12 starts Berenyi had a superb 2.41 ERA that, for the offensively challenged Reds (next to last in the league in runs scored), got him a record of 0-7. He was injured in May and, perhaps unwisely, chose to pitch through it — he was 1-5, 6.11 in his next nine appearances. A respectable season-ending 3.86 ERA unduly merited a dismal 9-14 and once again Berenyi’s agent sought greener pastures for his client. This time the Reds tried to accommodate their disgruntled hurler. A trade to the New York Yankees for catcher Rick Cerone during the season was allegedly vetoed by the veteran backstop, whose contract contained trade restrictions. In October the Detroit Tigers aggressively pursued Berenyi for outfielder Glenn Wilson but the pursuit dried up when the Tigers successfully re-signed free-agent righty Milt Wilcox in November.

A glimmer of hope surfaced for the Reds in general — and Berenyi in particular — in the spring of 1984. Improved offense was expected with the signing of free-agent slugger Dave Parker, while Berenyi produced perhaps his finest Grapefruit League campaign: a 1.29 ERA. Though the Reds offense improved slightly over preceding seasons, it was largely nonexistent in Berenyi’s first four appearances. Burdened with a record of 0-3 (it easily could have been 2-2 with run support), he complained “I’m not a loser. I’ve never been a loser.”16 But a different picture emerged in May. In two of three starts Berenyi could not get a single out as his ERA shot above 6. Two promising starts in June were followed by a disastrous outing against the Astros on June 12. Three days later Berenyi was traded to the Mets for three minor-league prospects.

Since the notorious “Midnight Massacre” seven years earlier (when the Mets dumped 11 players via four trades in one day), the team had suffered through hard times. But in 1984, under the guidance of their new manager, Davey Johnson, the league’s youngest team was competitive again. When Berenyi joined the Mets he became the most senior member of the staff despite just four years of major-league service under his belt. Johnson, who’d been in awe of Berenyi’s slider in an April 4 match against the Mets, was elated with the addition: “He’s going to fit right in here. … I liked what I saw from him the first time. He’s going to do just fine with us.”17 Berenyi’s season immediately turned for the better. With the Mets he went 9-6 with a 3.76 ERA and won five of his final six decisions. When Walt Terrell was traded to Detroit on December 7, Berenyi was projected as the Mets’ third starter in 1985.

But fate had something else in store as Berenyi struggled with a tender shoulder the following spring. He pitched only 13 Grapefruit League innings. These worries appeared to be for naught on April 12 when Berenyi came out of the gate with a spectacular seven-inning one-hit performance against his former teammates. The win was his only decision of the 1985 season. Berenyi pitched only 6⅔ more innings in two appearances before a tear in his rotator cuff was discovered. Surgery in May placed him on the shelf the rest of the season.

After the season Berenyi reported to St. Petersburg, Florida, to pitch in the winter Instructional League. But the shoulder did not respond. He instead rehabbed with Mets trainer Tom McKenna. Having to wait until spring to ascertain Berenyi’s status, the Mets traded with the Boston Red Sox for lefty Bob Ojeda. Even Berenyi sounded conflicted about a rapid return, stating, “It’s hard to keep from having second thoughts. Every now and then when you throw, your arm might feel funny. But then the next time, it doesn’t. You try to push it out of your mind but it’s difficult. Right now I feel great, and the doctor says there is no reason I can’t be ready for next season.”18

Berenyi reported to spring training early and began pitching throwing every other day under the supervision of pitching coach Greg Pavlick. When he experienced no pain, Davey Johnson predicted that “he will throw as hard as he used to, maybe even harder.”19 The manager confidently announced Berenyi’s return to the staff. But the righty did not begin the 1986 season in the rotation. In a cautionary approach, he was initially assigned to the bullpen and did not receive a starting nod until May 13. He started six more games but never worked beyond the sixth inning. Despite Johnson’s earlier optimism, Berenyi’s velocity was lacking. He proved hittable. Having generated a 6.35 ERA in July, Berenyi agreed to be assigned to the Tidewater Tides in the International League, where he showed little improvement. Shortly after the Mets secured a World Series win over the Red Sox, Berenyi was released. On January 23, 1987, he signed with the Montreal Expos and went to spring training as a nonroster invitee. It was not long before the shoulder problems resurfaced and he was released on March 11. Berenyi had a second surgery, whose success provided him the confidence to re-sign with the Expos in 1988. This stint also proved short-lived. In late February he signed a minor-league contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates, but was released before the start of the season. With a major-league ledger of just 142 appearances, Berenyi retired from baseball.

Berenyi returned to the Sherwood, Ohio, home he had built on a 25-acre tract he purchased in 1984. With a second residence in Florida, he worked for a resort/golf course in North Miami in the winters. Berenyi retained the winter home while forsaking his native state for New Hampshire. In 1993 his collegiate exploits were recognized with his induction into the Truman State University Athletic Hall of Fame.

Unfulfilled were the grand expectations surrounding Berenyi when he made his way through the professional ranks. His complaints of arm soreness were ignored — even ridiculed — as the hard throwing righty advanced. Those problems were unmistakable when two shoulder surgeries were unable to resurrect Berenyi’s once-promising path. Unknown is the career that might have developed had the Reds been more attentive when the aches and pains initially surfaced.

Sources other than those cited in Notes:

The author wishes to thank SABR members Bruce Slutsky, Randy Rice, and Anne Surman for their assistance.

Ancestry.com

technicians.truman.edu/csweb07/hallOfFame3/myXML.xml

Notes

1 Madeline’s younger sister, Dorothy Louise, married pitcher Ned Garver, whose major-league career spanned 14 years.

2 “Southern Averages,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1978: 48.

3 “McNamara Checks Band, Finds All on Key,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1979: 11.

4 “American Association,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1979: 39.

5 “American Association,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1980: 37.

6 “Rain Stops Berenyi Streak,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1980: 39.

7 “End of Trail Looming for Seaver,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1980: 21.

8 “Berenyi Runs Wild,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1981: 26.

9 “Soto’s Spurt Spurs Reds,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 33.

10 The victory was the last of four consecutive complete games for the rotation, a string that had not been reached by a Reds staff since five straight complete games in 1962.

11 “Reds: Pastore In Dark,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1981: 32.

12 “’Bullets’ Berenyi Finds the Range,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1981: 37.

13 “Reds Attack Dulled By Power Shortage,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1982: 34.

14 Ibid.

15 “Pete on Winning Side of Another Record,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1983: 6.

16 “Is Berenyi Trapped In Twilight Zone?” The Sporting News, April 16, 1984: 21.

17 “Young Hurlers Leading Mets,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1984: 21.

18 “N.L. East — Mets,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1986: 50.

19 “Pleasant Complications For Pitching-Rich Mets,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1986: 38.

Full Name

Bruce Michael Berenyi

Born

August 21, 1954 at Bryan, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.