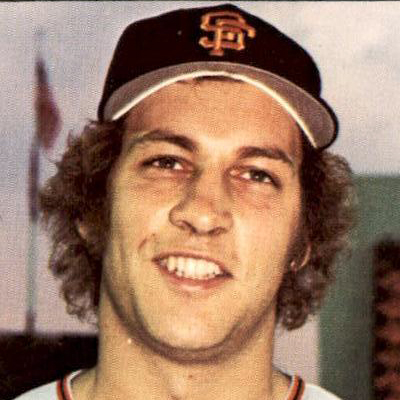

John Montefusco

The right-hander stood on the pitcher’s mound in Tucson, Arizona, watching his manager Rocky Bridges walk out for a visit. It was the eighth inning; the bases were loaded with his team in the lead. Bridges grabbed the ball and gave it a good rub. After placing it back in his pitcher’s glove he offered the following advice, “Kid, will you stop messing around? The Giants just called, you are going to big leagues. So stop worrying.”

The right-hander stood on the pitcher’s mound in Tucson, Arizona, watching his manager Rocky Bridges walk out for a visit. It was the eighth inning; the bases were loaded with his team in the lead. Bridges grabbed the ball and gave it a good rub. After placing it back in his pitcher’s glove he offered the following advice, “Kid, will you stop messing around? The Giants just called, you are going to big leagues. So stop worrying.”

On September 3, 1974, John Montefusco from Long Branch, New Jersey, arrived at Dodger Stadium, one hour before that night’s game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants. His new manager, Wes Westrum, quickly went over the signs while informing him that he would be the first pitcher out of the bullpen that evening. Montefusco did not get much of a chance to familiarize himself with the visitors’ bullpen. The Dodgers jumped out to a quick 4-2 lead, sending veteran Ron Bryant to an early shower before he had retired a batter. Westrum motioned to the bullpen for a relief pitcher. The newest member of the Giants strolled across the right field grass on his the way to be baptized by fire.

Years later, Montefusco admitted to having butterflies that evening. “But then I got to the skin part of the infield and Tito Fuentes was there and greeted me on my way in. And he said, ‘Come on kid, I know you can do this.’ So I gathered myself up to the mound, took the ball from Wes Westrum and I said, ‘I guess you need three strikes,’ because the bases were loaded and he said, ‘Kid, just don’t walk anybody.’ But I ended up getting a force out and I struck two guys out to end the inning. After that, it was easy.”

Montefusco finished the day by allowing one run on six hits in a nine-inning relief stint. Not only was he the winning pitcher, he also smashed a two-run homer in his first official at-bat in the third inning. He had walked the previous inning, scoring on a grand slam by Gary Matthews. His home run was unexpected. Montefusco admitted to asking Dodgers second baseman Davey Lopes if the ball had left the park. After the game, Montefusco rekindled some of the sparks of the two team’s classic feud with his postgame remarks. “I wanted to beat the Dodgers — I hate the Dodgers, I’m from New Jersey, and I’ve always been a Yankee fan.”

John Joseph Montefusco Jr. was born on May 25, 1950, in Long Branch, New Jersey, a shore community only a stone’s throw from the Atlantic Ocean. He grew to love the national pastime. While in high school, he played shortstop. John was tall and lean, distributing all of his 150 pounds upon a six-foot frame. His physique and the fact he did not begin pitching until his senior year in high school did not make him attractive to most major league scouts. Still, Montefusco accumulated a 6-0 record that included a no-hitter. While others his age were being scouted by major league teams or offered athletic scholarships, Montefusco was completely overlooked.

He landed on the campus of Brookdale Community College in Lincroft, New Jersey, pitching for the Jersey Blues in 1971 and 1972 and setting several school pitching records. He held the record for the lowest ERA for a single season at 0.65, most consecutive victories with 16, career strikeouts with 202 and 19 Ks in a single game. Even his 18-2 record for his two seasons was not enough to attract the attention of big-league scouts. Montefusco ended up taking a job as a clerk with a large telecommunications company and spent his summers playing semi-pro ball at the New Jersey shore.

In an interview with Bill Ballew for his book The Pastime in the Seventies: Oral Histories of 16 Major Leaguers, Montefusco reflected upon his fate. It seems that the only team that showed an interest was the San Francisco Giants. “I think the Giants did somebody a favor by signing me.” The favored somebody was probably Frank Porter, the owner of the semi-pro team that Montefusco played for. Apparently Frank had been bugging John Kerr, a local scout and former American League infielder, until he finally agreed to sign Montefusco. Porter was aware of the right-hander’s talent and had almost as much confidence as the young pitcher did.

It did not take long for the brash pitcher to make his first bold prediction. Montefusco professed that he would be pitching in San Francisco within two years. He beat his prediction with a month to spare. “You don’t get much help in the minor leagues, you either make it on your own or you don’t make it.” The rookie pitcher also felt that one major advantage of pitching in the minors was the ample opportunities to pitch. “We were on a four-man rotation back then. It wasn’t like it is today, where organizations are trying to save everybody and use starters every fifth day and only let them throw 100 pitches. Back in the early seventies, you went out every fourth day and they didn’t care if you threw 160 pitches.” He praised Gordy Maltzberger, who helped him during his first spring training. Maltzberger felt that Montefusco had a good enough curveball for the big leagues. Ironically, Montefusco admitted that he never threw it during a game. Instead, he relied upon a slider or a slurve to accompany his fastball.

His spring training audition placed him as the 13th pitcher on the 1973 Decatur staff. Decatur was the Giants’ Class AA entry in the Midwest League. Montefusco posted a 9-2 record with a 2.18 earned run average. He spent the following season with Amarillo of the Texas League before moving up to Phoenix. The young right-hander accumulated an 8-9 record at Amarillo and a 7-3 mark with Phoenix before his call up to the parent club.

Montefusco was impressive during his debut 1974 season. He began turning many pages in his biography. One was the creation of a nickname that would be his identity for his entire career. The nickname “The Count” originated during a game he pitched in El Paso. He won, 9-1, and the next morning’s headlines declared him the “Count of Monty Amarillo.” Then after his debut with the Giants, Al Michaels, the San Francisco announcer, bestowed the title of “The Count of Montefusco,” and it followed him for the duration of his major league career.

The young Giant pitcher did not waste any time tossing his first shutout. Before the game, Wes Westrum advised him not to finesse the Reds but challenge them. Montefusco went on to allow seven hits and issue two walks while striking out seven, only 19 days after making his debut. He also hit his second home run, which was especially impressive since he played with the designated hitter rule while in the minors. Don McMahon, the Giants pitching coach, described Montefusco, “Electricity just seems to purr from him. It’s in his smile, his refreshing honesty and his arm.” Montefusco completed his first major league campaign with a 3-2 record, 4.81 ERA, and 34 strikeouts in 39 1/3 innings.

While 1974 was a fairly impressive season for the young right-hander, it also represented a low point since the Giants had moved to California. The Giants finished in fifth place, 18 games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers. The team’s disappointing season was also reflected by its attendance; only 519,991 fans went through the Candlestick Park turnstiles. Even with the obvious ineptitude, there was hope for the upcoming season. For instance, the team did not have a player over the age of 30. Their one veteran, Bobby Murcer, did not turn 29 until May. Manager Westrum was convinced that pitching would become the team’s strong suit. the club began the season with a staff that included Montefusco, John D’Aquisto, Mike Caldwell, and Jim Barr. The rotation was complemented by a bullpen comprised of Randy Moffitt, Charlie Williams, and Dave Heaverlo.

The Count got out of the gate fast in 1975. He started with a four-hit shutout over the Atlanta Braves. Then on April 18, the Giants traveled to Los Angeles to play the reigning National League champions. All he did was fashion a 3-1 complete game. “I really get psyched up for the Dodgers and Reds. I think the Dodgers are the best team. I don’t think the A’s are.”

While complimenting his bitter rivals, he loudly predicted that the Giants, not the Dodgers, would win the NL Western division. After beating the Dodgers in April, Montefusco defeated them two more times, including a 1-0 shutout against Andy Messersmith, giving up eight hits and striking out 10. In his postgame comments, he dedicated the game to one of the Dodger players: “This one was for Ron Cey. He said in the papers that I wasn’t a good pitcher and that I wouldn’t win 10 games.” Leaning back with a beer in hand, he continued, “This is the greatest game of my life, I’ll tell you better than the first time. This time, I shut out the Dodgers — I was really psyched.”

Thus the brazen pitcher penned a new chapter in one of the longest rivalries in the history of the sport. The Dodgers and Giants had been hated enemies ever since the early years of the National League. The conflict could be traced back to a rift between former Baltimore Orioles teammates John McGraw and Wilbert Robinson. It intensified in 1951 with Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” It picked up after the teams moved to the West Coast, when the Dodgers and Giants squared off for a playoff series in 1962 that the Giants won. It took an ugly turn on August 22, 1965, when Juan Marichal hit Johnny Roseboro over the head with a baseball bat. Now, the Count rekindled the mutual dislike.

After the Dodgers shutout, the right-hander lost to the Cubs, and then reeled off three consecutive victories. The winning streak stopped with the help of the Cincinnati Reds when Montefusco got pounded, 11-6. A long home run from Johnny Bench punctuated the loss. The homer’s estimated distance of 500-plus feet might have been influenced by the Count’s bold prediction before the game. He claimed that he would strike out the slugger four times. Montefusco recalled the homer in an interview with Bill Ballew, one that was sprinkled with some humor. “Johnny Bench hit the longest home run ever hit off of me. As a matter of fact, he hit the cement façade on the third deck of Riverfront Stadium. When we got back to Candlestick, my mail was stacked up in front of my locker. As I was going through my mail, I noticed an envelope with Cincinnati Reds letterhead. I wondered what the heck it was, so opened it up and it was a bill for $957. It read, ‘For damage done to the cement façade at Riverfront Stadium from Johnny Bench’s home run.’ Chris Speier had filled it out and sent it. That was funny.”

Montefusco finished the 1975 season by winning five out of seven games, ending up with a record of 15-9, 2.88 ERA, and 215 strikeouts. His strikeout record was the most by a Giants rookie since Christy Mathewson, who had 221 in 1901. It was also the most for a National League rookie since Grover Cleveland Alexander’s 227 in 1911. On October 30, 1975, the Count was named the National League’s Rookie of the Year, receiving 12 of the 24 first place votes; Gary Carter garnered nine while Larry Parrish, Manny Trillo, and Rawly Eastwick received single votes.

Modesty was never one of Montefusco’s strongest virtues, and his braggadocio endeared him to the San Francisco faithful as much as his talent on the mound. After receiving the award, he responded not with thanks but a promise. “Next year, the Cy Young Award. Why should I stop right here? I want to be the best pitcher in baseball. I said that I could win 15, but that was a minimum. I had my sights on 20. I was kind of disappointed. I thought that I could have done better.” The rookie’s style was reminiscent of Dizzy Dean: “It ain’t bragging if you can do it.” Even with Montefusco’s fine season, the Giants finished in third with an 80-81 tally.

In 1976, Montefusco picked up were he left off the previous year, both with his loquaciousness and performance. He made his first start against the Dodgers, the team that he loved to hate. To no one’s surprise, the Count predicted a shutout. His prophecy was shattered in the first inning. The newly acquired Dusty Baker greeted him with a home run. As Baker returned to the dugout, Bill Russell jumped out and waved a towel towards the pitcher. Although Montefusco did not get the shutout, he hurled a strong 7 1/3 innings for a 4-2 victory. “The Dodgers should stop worrying about waving a towel and think about throwing in the towel. We’re thinking about the Reds.” It was obvious that the Dodger-Giants rivalry was intact.

After the game, Montefusco fielded questions concerning the sophomore jinx. Once again, he admitted his intentions of winning the Cy Young Award. “I have to win 20 games to win it and now I need 19 more and I’m going to get 19. I’m going to do it. Everyone played a hell of a game behind me today and I love to beat the Dodgers because I hate them so. Now I hear that they’re making predictions against me like I do against everyone else. They say that I’ll beat them only 1-0.”

The Count faced the Dodgers again on June 2. He entered the contest with a 6-3 record and was coming off two consecutive three-hit shutouts and a string of 21 scoreless innings. John was anxious to extend this streak against his nemesis. Unfortunately, the streak came to an end in the third inning when Los Angeles sent ten batters to the plate to score five times. As he departed, the Count, in typical fashion, waved his cap to the jeering crowd. Montefusco and his favorite opponent met again on June 26, with the pitcher scattering six hits before leaving with a blister in the eighth inning. The Giants went on to a 4-2 win that included homers by Matthews and Murcer.

Although he sported a 7-8 record, Sparky Anderson, the manager of the National League All-Star team, selected Montefusco for the team’s pitching staff. The Count did not let Anderson down. In the two innings that he pitched, he faced four future Hall of Famers: Carl Yastrzemski, Rod Carew, George Brett, and Carlton Fisk. He completed his work allowing just two walks while striking out two.

Montefusco squared off with the Dodgers on July 31. It was not his best effort; he won 6-3, giving up eleven hits to raise his personal record against the Dodgers to 6-3. “I’m glad to win but I’m not overwhelmed. I wanted to shut ’em out so I could shut up [manager Tommy] Lasorda. He’s been all over my case. He’s been saying I’ll never beat ’em again, it’s good to beat ’em by any score.” That day, another page was turned in the Count’s personal rivalry with the Dodgers. The new participant came in the form of the 6-foot, 180-pound Reggie Smith. Years after his career was over, Montefusco admitted that Smith was the toughest batter that he faced. That day, Smith took him deep and went 3-for-4.

While the Count completed another season to be proud of, it was on September 29 that he had what he later referred to as “the greatest day of my life. I just can’t believe it.” John pitched a 9-0 no-hitter against the Atlanta Braves on the last game of the 1976 season. “It’s the perfect ending to a perfect day.” Years later, he shared his emotions from that day with author Bill Ballew. “At the end of that game, it was the greatest feeling in the world. It is the greatest high that I have ever experienced in my life. The adrenaline that I felt in the ninth inning was incredible, because adrenaline that was rushing through my body would have allowed me to get Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and anybody else in the ninth. I felt no pain and felt like I was ten feet off the ground in the ninth inning.”

While Montefusco considered this game his greatest moment, it was not absent of disappointment. In the fourth inning, he walked Jerry Royster; otherwise it would have been a perfect game. The post-game interview was shown on NBC’s Today show the next morning. The cameras showed him cradling a bottle of champagne that he received from Ted Turner. It had been the Braves’ fan appreciation night. Only 1,300 fans attended the game and for some reason the game was not televised on Turner’s station. In fact, the public relations department actually needed to call the news networks to inform them that a no-hitter was being pitched. Montefusco finished the season with a 16-14 record, 2.84 ERA, and 172 strikeouts while pitching six shutouts.

While Montefusco had enjoyed much success during his brief professional career, 1977 marked his first of several physical setbacks. The injury occurred on May 26 during a contest with the Cincinnati Reds. The Count suffered a severely sprained ankle during the second inning as he ran to first base. It occurred after laying down a bunt that he had a chance to beat out. Joe Morgan was covering first base, and the throw came in high and to the outside of the base. Morgan ended up standing on the middle of the bag. Instead of plowing into him, Montefusco decided to go toward the corner of the base. That is how he turned his ankle, causing him to go down and head for the disabled list.

Montefusco was not activated until July 7, and he started three days later, allowing four runs in the fourth inning against the Braves. Dave Heaverlo came in holding the Braves to one more run and the Giants won 12-5, enabling San Francisco to sweep the doubleheader. The Giants’ right-hander finished with a less than stellar season at 7-12, 3.49 ERA and 110 strikeouts. It marked the fourth consecutive sub-.500 season for San Francisco.

The following season was a different story. The Giants snapped out of their losing ways in 1978 and finish in third place with a final tally of 89-73. In their second year under manager Joe Altobelli, San Francisco featured a young Jack Clark, who hit .305, with 25 homers and 98 runs batted in, and Bill Madlock who chipped in with a .309 average along with 15 homers. The team’s two lefty starters, Bob Knepper (17-6, 2.63) and Vida Blue (18-10, 2.75), led the way.

While the Giants played well together, they did not necessarily get along. The first signs of dissension could be traced to March 8 at the Casa Grande spring training facility. On that day, the Count and Madlock had a publicized altercation. It seemed that Madlock took exception to Montefusco’s public criticism of the ability of certain teammates, especially the fielding of a certain Giants second baseman. Then there was the disappearance of the newly acquired Vida Blue, who was not enamored with moving across the bay from Oakland. On a lighter note, John asked the Giants and was given permission to leave spring training to marry his girlfriend, Dory Samples.

Montefusco’s season started off with another injury. On April 7, with a 2-0 lead in the sixth inning, he again sprained his ankle while stepping off the mound. The two Giant relief aces, Randy Moffitt and Gary Lavelle, let the game get away, and San Diego went on to win 3-2. The Dodgers-Giants rivalry refueled in 1978, ignited via a mutual dislike between the Count, Reggie Smith, and manager Tommy Lasorda.

On May 28, the Giants beat the Dodgers in front of 56,103 fans in San Francisco. Smith took Montefusco deep to tie the game, knocking him out of the box. The Dodgers outfielder accented his home run by walking the last fifteen feet of his trot home. Eventually Darrell Evans drove in the winning run in the seventh inning to give the Giants a 6-5 victory.

After the game, Lasorda launched the first shot of the battle of words. “The Giants haven’t shown me anything. The only thing is that they must have read Wee Willie Keeler’s book on how to hit ’em where they are and where they ain’t.” Lasorda did not miss an opportunity to comment on the pitching performance of Montefusco. John had not distinguished himself with his two starts against the Dodgers; the Giants right-hander yielded 12 runs on 18 hits, but still the team was able to win both games. “I could make a fortune by buying him for what I think he is worth and selling him for what he thinks he is worth. Twelve runs and eighteen hits, damn.”

On August 13, Montefusco and Smith met again. This time, Smith clubbed homers off the Count in both the first and fifth innings. Montefusco was not around at the conclusion, but the Giants won, 7-6, in the 11th, and moved into first place. Unfortunately, a little more than a month later on September 17, they fell down to third place and finished the season there. Montefusco finished with a decent season at 11-9, a 3.81 ERA, and 177 strikeouts.

Both Montefusco and the Giants returned to mediocrity in 1979, the club finishing in fourth place, 19½ games off the pace, and Montefusco at 3-8, 3.94 with 76 strikeouts. The clubhouse was a disaster: Vida Blue verbally assaulted San Francisco writers on several occasions; pitcher Ed Whitson punched out shortstop Roger Metzger; and Montefusco left Candlestick Park after losing to the Cubs, promising never to come back. Manager Joe Altobelli was fired that September, and his coach Dave Bristol, a disciplinarian, replaced him.

Any doubts concerning the health of the Dodger-Giants rivalry were answered on April 24, 1980. Reggie Smith hit a homer off the Count early and raised his fist as he approached second base. The Dodgers won in the tenth inning. Montefusco departed in the seventh with the score knotted at two. This was also a year that John’s name returned to the sports page headlines. On June 19, the Giants defeated the Mets, 8-5. Bristol lifted Montefusco, who was angry about being removed in the ninth inning with a 8-2 lead but with two men on and no outs. After the game, Giants players found their pitcher and Bristol grappling on the floor of the manager’s office. Several years later, Montefusco wished the incident did not occur. “I had a habit of not only burning bridges but also blowing them up.”

Montefusco’s relationship with the Giants dissolved in 1981, when he was traded to Atlanta for a disgruntled Doyle Alexander. Montefusco lost and won games against his former team during the first week of the season, which was soon interrupted by a baseball strike. Montefusco finished his first and only season in Atlanta with a record of 2-3, 3.49 ERA, and 34 strikeouts. He was suspended at the end of the year, learning of it by watching television in an Amarillo, Texas, motel. The reason for the suspension was his failure to make a plane flight for the last series against the Cincinnati Reds. The Count claimed that his manager, Bobby Cox, gave him permission. After the season, he asked to be traded, then insisted instead on being released so he could become a free agent. The Los Angeles Times reported that if Ted Turner had not spent all of a $15 million loan on non-baseball matters, the Count would still be pitching in Atlanta.

As a free agent, Montefusco next went to the pitching-starved San Diego Padres, who in 1982 were counting on veterans Rick Wise, John Curtis, and the Count. With Montefusco riddled with numerous injuries over the past seasons, he borrowed a page from the past to carry a no-hitter into the seventh inning against the Reds until a single by Dave Concepción. He completed seven innings, allowing only the single, and beat the Reds 4-1. That August, he tossed his first complete game since April 1980 by beating the Astros, 5-2. Then on September 22, he defeated the hated Dodgers by a score of 3-0. When asked whether his personal rivalry was still alive, his eyes lit up like a kid at the gates of Disneyland. “Not too many people are very fond of the Dodgers, just because they’re world champions. Everyone wants to beat the world champs. But I’d want to beat ’em even if they are in last place.”

On October 2, 1982, Montefusco started a game against the Atlanta Braves, a game the Padres eventually lost. The loss prevented the Los Angeles Dodgers from clinching the NL West division title. In essence, Montefusco beat the Dodgers unintentionally, much to the chagrin of Tommy Lasorda. On the evening of the game, the Dodgers manager and broadcaster Vin Scully listened to every out on a transistor radio. The loss really irked Lasorda. “He’s all mouth, this guy, talking about how badly he wanted to beat the Dodgers. He’s paid to beat everybody. … Heck, I don’t even want to talk about him. I only talk about .500 pitchers.”

The Dodgers lost to the Giants the following day anyway and the Braves won the division. Montefusco ended the season by finishing 10-11, 4.00 ERA, and 83 strikeouts. It was not a winning record, but an improvement over his last few seasons.

Montefusco returned to San Diego for the 1983 season. He let everyone around know that he intended to work on his image. “I can’t do all those crazy things I used to and I can’t keep on popping off with my opinions. I’m no longer single. I have a family now, so I have to get respect for my children.”

The one thing that did not change was his confrontational relationships with his managers. His skipper in San Diego was Dick Williams. After he was taken out of a game against the Cubs, Montefusco stormed off to the clubhouse. Later, he claimed ignorance concerning the rule that players could not leave the bench during a game. Because of his violation, Williams banished him to the bullpen. This did not make the Count happy. His manager considered him the team’s stopper. Still, it was not a job that Montefusco cared to adapt to.

Eventually, his agent, Dick Moss, was given permission to shop for another team. On August 26, one of Montefusco’s dreams became a reality. Not only was he being traded to another team, he was headed to the New York Yankees. San Diego received two outstanding prospects in return. John was elated by the news. “I like it. I’m from New Jersey and the Yankees are the team I have followed my entire life. It’s like a boyhood dream for me, although I guess everyone who has ever played for the Yankees says that.”

In his Yankees debut, he beat the Angels by a score of 7-3, but he had to leave the game after six innings with a blister. It marked only the fourth time that a right-handed starter won for the Yankees that season. Both manager Billy Martin and catcher Rick Cerone were impressed by the Count’s performance. On September 3, Montefusco earned his second victory since joining the Yankees, also winning the admiration of his teammates. Montefusco turned in a 5-0 record that included a 3.32 ERA with 15 strikeouts for the Yankees. Although he professed his love for the Yankees, he stated, “I might test the free-agent market now.”

On October 18, 1983, Montefusco decided against becoming a free agent and re-signed with the Yankees. The agreement was worth $2.3 million. His combined record with the Padres and Yankees was 14-4. Unfortunately, this proved to be his final productive season. The years that followed saw him marred by several injuries. The 1984 season did not work out the way he hoped. It started with a sore hip, and then on May 4, he suffered injuries from a car accident. After he retired, he blamed the accident for his developing poor fundamentals. Then, when it seemed that he was back on track, he developed and broke a blister on his pitching hand in the eighth inning against the Baltimore Orioles on September 26. He finished with a 5-3 record, 3.58 ERA, and 23 strikeouts.

The nightmare continued for Montefusco in 1985. He tossed only seven innings the entire season. He spent most of the season on the disabled list because of a sciatic nerve condition in his left hip. His disabilities contributed to a disappointing 0-0 slate, 10.29 ERA, and only two strikeouts. After the season, he had two holes drilled into his hip, and an electro-biology machine became his constant companion. The Yankees decided to release him in November.

Because of his competitive demeanor, the Count embarked upon a startling comeback. It was so successful that Sammy Ellis, the Yankees’ pitching coach, was convinced to consider him a significant piece to the team’s pitching staff in 1986. Ellis felt that Montefusco could contribute in the bullpen or as a spot starter. Since the Yankees had released him, Montefusco could not re-sign until May 15. This led the brash right-hander to let it be known that he was not averse to signing with another team. He ended up staying in New York. By May 21, he had relieved four times, allowing no runs in five and two thirds innings. But the Count soon returned to the disabled list. It soon became apparent that his pitching career was over. The culprit was a degenerative hip condition that made it impossible to pitch without pain. Montefusco announced his retirement on September 28, 1986. He finished the season at 0-0, 2.19 ERA, and three strikeouts. His career totals ended up at 90-83, 3.54 ERA, and 1,081 strikeouts.

Montefusco became involved with several interests during his post-baseball career; one was harness racing. He was fond of attending races at Monmouth Park Raceway. In fact, it was at a charity harness racing event that he initiated a relationship with former Yankees pitcher Sparky Lyle. Baseball always ran through Montefusco’s veins and Lyle was the manager of the Somerset Patriots of the independent Atlantic League. He became the team’s pitching coach in 2000. The team won league championships in 2001 and 2003. Montefusco was given much credit for the team’s great pitching staffs.

The Count had better luck between the white lines than with his personal life. Since the late 1990s, he has experienced several domestic problems with his ex-wife Doris, who charged him with rape and domestic violence. Montefusco was acquitted in November 1999 of sexual assault charges, but only after spending two years at the Monmouth Correctional Institution. He was also assessed $405 in state-mandated fines. Montefusco sued ESPN unsuccessfully on a defamation claim. The telecast had made an analogy to O.J. Simpson, “another ex-athlete accused of domestic violence.”

Unceremoniously, on September 22, 2005, Montefusco resigned his position a few weeks before the league playoffs. He cited differences with the organization concerning the handling of the pitching staff. Some felt the blame was caused by his ejection from a game against the Atlantic City Surf, when he was filling in for Lyle. The Patriots lost by a score of 3-1. After being tossed, he proceeded to kick dirt on the first base umpire, a la Billy Martin. The Somerset ball club felt that his resignation was no surprise. Montefusco expressed an interest in managing and did not want to return as the pitching coach for the 2006 season.

It is anyone’s guess whether the Count will surface as a manager somewhere. If he does, it may be the first time he could get along with the team’s manager.

Sources

Newspapers (1974-1986)

Chicago Tribune, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Syracuse Herald-Journal, Washington Post

Books

Ballew, Bill. The Pastime in the Seventies: Oral Histories of 16 Major Leaguers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002.

Ashmore, Mike. “A Sit Down with Pitching Coach John Montefusco,” September 13, 2004, SomersetPatriots.com.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 2nd ed. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America Inc., 1997.

Schulman, Henry. “Still Down for ‘The Count,’” San Francisco Chronicle. August 29, 2006.

Somerset Patriots program, 2004

Stanchak, Scott. “Montefusco Resigns from Position as Patriots Pitching Coach,” Hunterdon Democrat, September 22, 2005.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. 9th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1993.

Online

BaseballLibrary.com (www.baseballlibrary.com)

Baseball-Almanac.com (www.baseball-almanac.com)

TheBaseballCube.com (www.thebaseballcube.com)

BaseballReference (www.baseball-reference.com)

Retrosheet (www.retrosheet.org)

The Baseball Index (www.thebaseballindex.com)

SABR Encyclopedia (www.sabr.org)

Full Name

John Joseph Montefusco

Born

May 25, 1950 at Long Branch, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.