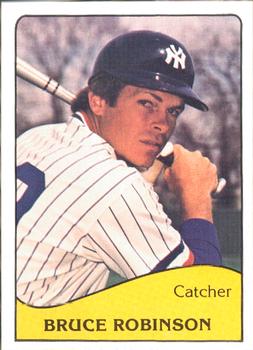

Bruce Robinson

As he walked to elementary school in La Jolla, California, Bruce Robinson tested his throwing arm with rocks. “I had to hit every sign from a certain distance or I couldn’t go to school,” he said. “I was on a mission from the time I was about 10 years old to become a major league baseball player.”1

Robinson achieved his goal, playing in 38 games from 1978 to 1980 with the Oakland Athletics and the New York Yankees. His brief career was punctuated with moments connected to headline-generating owners — Charlie Finley and George Steinbrenner. Robinson’s intertwined lifelong passions of baseball and music also generated recognition by the United States’ two iconic Halls of Fame — Baseball and Rock and Roll.

In the 1940s Bruce’s parents moved to San Diego from Minnesota during his father’s Navy service. His father John was a banker and estate planner; he was also a baseball fan who saw minor leaguer Ted Williams hit .366 for the Minneapolis Millers in 1938. He shared his love of baseball with the family and coached youth baseball for 17 years.2

Bruce Philip Robinson was born on April 16, 1954, the youngest of three brothers. John Jr. and Dave were 10 and eight years older respectively. Bruce was inspired watching them play Little League and so anxious to join them that from his crib at two years old, he threw a baseball through the living room window.3

His mother Kathleen was at home and helped the boys practice. “We had a baseball with a rope on it,” a homemade practice aid named the “twirl-a-round,” said Robinson. “My mom would swing it for us. We’d hit it one way and it would go back the other way. She’d stand in the middle and that’s how we learned to switch hit.”4

In Little League he pitched, played shortstop and catcher. “Baseball, by the time I was 10 or 11, was almost like a business to me,” he said. In 1967 when Johnny Bench joined the Cincinnati Reds, Robinson decided to become a full-time catcher. “He was the guy I looked up to.” In 1969, before 10th grade, he was invited to play summer American Legion baseball with rising junior and senior varsity players. “I started as a 145-pound catcher…and I had a great arm. That was my ticket,” he said.

As a sophomore starting catcher in 1970 Robinson hit .281.5 One MLB scout said he would have been drafted that year, if permitted, adding that he was “everything you look for in a catcher.”6 He hit left handed and threw right handed and was 5’ 11”, 165 pounds and growing.

That summer the Robinsons visited brother Dave, an outfielder with the Triple-A Salt Lake City Bees. “I put on a Padres Triple-A uniform and went out and took batting practice” said Robinson. “I hit home runs left handed and right handed. At Salt Lake City the ball jumped. I said to myself, ‘“I can do this.”’

As a junior in 1971 he hit .338 and in one game picked off five baserunners.7 “He studies the game more than any player I’ve seen,” said La Jolla High School coach Al LaMotte.8 Robinson’s reputation grew when brother Dave was called up to the major leagues in 1970 and played 22 games for the San Diego Padres.9

During the winter of his senior year Robinson was offered baseball scholarships by USC, UCLA, and Arizona State, powerful West Coast baseball universities. Concerned about Stanford’s academic rigor, he had thrown away its recruitment letter. But when family friend George Thacher, Stanford’s third baseman from 1963-65, heard about Robinson’s scholarship offers from rival baseball programs he engaged the Stanford baseball network.10 The effort earned an endorsement from San Diego Red Sox baseball scout Ray Boone who confirmed that Robinson could be a high round amateur draft pick. Stanford coach Ray Young invited Robinson to visit. and enlisted Boone’s son Rod, the Cardinal’s 1971 MVP, to lead the tour.

Boone hosted Robinson at his fraternity house and transported him in his Lotus Europa. After a Friday night steak dinner, they cheered Stanford to a basketball victory in packed Maples Pavilion. On Saturday after another win, jubilant students poured on to court. “The floor is shaking. Here I am, 17 years old. This is pretty cool,” said Robinson. On Sunday night, back home, Young called Robinson to offer a full scholarship. He accepted.

By 1972, his senior year, Robinson had grown to 6-feet-2 and 185 pounds. “His biggest asset is the way he can catch,”said La Jolla High School coach Al LaMotte.11 Robinson hit .436 and led the team in all offensive categories with an OBP of .620.12 “There was some talk he might be the very first pick in the draft,” said Allan Simpson, founder of Baseball America. Robinson’s commitment to Stanford dropped him to the fourth round. A bonus offer from the White Sox fell far short of Robinson’s $75,000 target so he chose to go to college.

That summer Robinson previewed college baseball. He was invited to play for the Alaska Goldpanners of the Alaska Baseball League, the flagship team of the premiere national summer college baseball circuit.13 “Bruce was one of the rare kids who came up there out of high school,” said Simpson, the team’s assistant general manager in the mid-1970s. It was the start of a two-year baseball test. Backing up future first round draft pick catcher Steve Swisher, Robinson hit .220 with limited playing time.

That fall Robinson’s academic fears disappeared. He eventually graduated two quarters early with a degree in Economics, attaining an overall 3.40 grade point average. “I had a higher grade point average than I did in high school,” he said. In 1973, a senior catcher pushed freshman Robinson to the outfield. He played in 31 of Stanford’s 57 games, with 23 hits, a .261 average, a home run and an OPS of .696.

For the Goldpanners in 1973, with his playing time limited by hand injuries, Robinson hit .294 with an OPS of .813. That summer after two broken fingers, he adopted the protective measure of his role model, Johnny Bench, hiding his throwing hand behind his right calf for each pitch.

At Stanford in 1974, still in the outfield, Robinson was a conference all-star with a .271 batting average. Overall, during two years as a Cardinal he hit .267, with an OPS of .712. He had 10 extra base hits and one home run. The uninspiring results from 119 college-level games prompted him to plan for an academically-focused final two years. He was accepted into a junior year abroad program in England. As an economics major he was also offered admission into the University of Chicago MBA graduate program.

His third summer as a Goldpanner in 1974 restored Robinson’s baseball career trajectory. “He took charge behind the plate,” said Simpson. “He really matured into a ballplayer that year. His power came on. He hit for average like you hadn’t seen him do before. Every aspect of his game came to the surface that summer.” Robinson was among nine future major league players on the Goldpanners. 14

He hit .346, had an OPS of 1.201 with 14 home runs and 52 RBIs in 64 games.“I started swinging harder, more upper cut, not being defensive. I got cocky and aggressive,” he said. The Goldpanners won their third straight National Baseball Congress championship.15

The breakout summer prompted Robinson to scrap his junior year abroad and graduate school plans.16 As the Cardinal’s starting catcher in 1975, Robinson hit 13 home runs to break Rod Boone’s team record and had an .875 OPS despite a .249 batting average. In June, Robinson was gratified to be a first-round draft pick of the Oakland Athletics (21st overall), but said, “I didn’t know how cheap Charlie Finley was.”

The Athletics bonus offer of $20,000 was well below the standard for a late first-round pick. Robinson was seeking $75,000. Negotiations dragged so Goldpanners coach Dietz invited him back to Alaska. To avoid injury, he played outfield. Two months after the June draft he remained unsigned. The Goldpanners started their annual road trip to the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. Robinson was sitting by the swimming pool in Pueblo, Colorado, when one of his teammates told him, “Charlie Finley is on the phone.”

Certain it was a prank, Robinson didn’t budge. A few minutes later the same message was relayed. He walked into the hotel, picked up the phone and received this greeting: “This is Charlie Finley.”

Finley and Robinson remained far apart, so Bruce called his brother Dave, whose brief major league career had ended in 1971. Dave emphasized the importance of signing as a first-round pick and playing pro baseball that year and advised him to overlook the disappointing bonus amount. Robinson signed for $28,750 and joined the Single-A Modesto A’s. In 24 games he hit .250 with five home runs and an OPS of .806. Robinson played in Double-A Chattanooga in 1976.

“It was a big jump from college to Double-A ball,” said Robinson of the 1976 season: “It wasn’t the speed of the game. It was the pitching. They weren’t making as many mistakes.” Out of frustration, Robinson tried switch-hitting, but that experiment was quickly ended by orders of Charlie Finley. Despite Robinson’s .200 batting average and .296 slugging average, manager Rene Lachemann said he demonstrated leadership on and off the field. He hit fourth or fifth in the lineup. “He had plus power, an outstanding arm, and was very good behind plate, blocking, and diligent worker,” said Lachemann, who managed Robinson at three minor league levels, Modesto, Chattanooga, and San Jose.

Chattanooga Lookouts 1976 pitcher Brian Kingman said, “He called a great game. Framed the pitches well. And that was the real key to success. It’s almost like having a veteran catcher.” At a critical moment that required a conference, he said, “It was like having a scout come out to the mound.”

On the lighter side, to rest better on long Southern League bus rides, Kingman and Robinson configured a plywood platform on top of four seats for sleeping. It displaced two more seats than their space allocation, so they told teammates it was to help manage Robinson’s sore back.

To manage the grind of his first full professional season, Robinson would play popular songs on his acoustic guitar. “It went on every road trip. Every bus trip. Every airline flight,” he said. He bought the guitar in 1974 in Wichita at the National Baseball Congress tournament with the Goldpanners. Like baseball, music took root in his childhood. Robinson’s guitar performance debut was in 1965 at a Parent Teacher Association meeting when he was eleven.17 He sustained his passion for music through his record collection and was immersed in the emergence of rock and roll, especially the Beatles.

Another source of support was spiritual. On Sunday mornings in Chattanooga Robinson and teammate Ron Bell would lead a Christian chapel service. With temptation, struggle and uncertainty ever present in the minor leagues, Robinson found strength in Christianity. “It’s that day-to-day living when you want to have that barometer there. That you know right from wrong…and what does happen is okay, and there is a reason,” he said.

In 1977 Robinson hit .275 with an OPS of .721 in 64 games for Chattanooga and was promoted in mid-season to Triple-A San Jose. In 1978, the Athletics’ Triple-A franchise moved to Vancouver. Manager Jim Marshall and 31-year old catcher Tim Hosley primed Robinson for a promotion to the major leagues. Robinson remembered “I got that confident cocky air again. And I had my best year ever.”

Robinson said Marshall “played me like a top…He knew when to put me in…He would sit me at the right point. He had my back and he wanted to see me make it.”

Robinson recalls Hosley telling him: “You catch. I’ll DH. This is your year. We’re getting you to the big leagues.”

In August 1978 Robinson was hitting .299 with an OPS of .820 and 73 RBIs in 102 games when Oakland starting catcher Jeff Newman was injured. Robinson was called up. When he arrived at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum for the August 19 game against the Red Sox the lineup was already posted. “I didn’t have time to get nervous,” he recalled.

In the bottom of the second his first major league at bat produced an RBI single off left-hander Bill Lee, giving the A’s a 1-0 lead. “When I got to first base I felt like I was seven feet tall,” said Robinson.18 His MLB debut paired him with brother Dave Robinson to join the other 413 brothers who played in MLB.19

Robinson got a second hit off Lee and one off Dennis Eckersley the next game. After seven games, the left-handed hitting Robinson had eight hits, including six off some of the toughest lefty pitchers in the league — Mike Flanagan, Scott McGregor, Ron Guidry, and Sparky Lyle. “I can see the ball. There’s hitting backgrounds. The lights are good,” said Robinson, noting he was very relaxed at the plate. Still, teammate Wayne Gross cautioned him about his .333 average, saying “Robby, it’s not that easy.”

After 16 games, Robinson was hitting .333, with hits off dominant pitchers including Catfish Hunter and Jim Palmer.20 On September 8 Jon Matlack held Robinson hitless. Newman returned to the lineup the next game and Robinson played less. “My average started going down and it ended up where it belonged,” he laughed. For the season he hit .250 in 84 at bats.

Defensively Robinson’s throwing arm sent a message to baserunners. He threw out 46 percent of the runners in stolen base attempts. That was fifth in the league for catchers playing at least 25 games and well above the league average of 38 percent.21

The day after the season ended, Monday, October 2, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed Commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s authority to regulate the sale of players from one team to another.22 Four months later, as spring training began in 1979, Robinson was part of a third Oakland player sales dispute. Again, Finley was involved, trying to generate revenue for his cash-starved Oakland franchise.

In 1979 the Yankees were looking for a left-handed hitting catcher, as veteran Thurman Munson was turning 32 and was expected to catch fewer games.23 On February 3 the Yankees bought Robinson, but it took two weeks to complete the transaction. 24

When he was picked up at the Fort Lauderdale airport, as Robinson remembered, Yankees General Manager Cedric Tallis told him: “There’s a problem…We don’t want you going near the media.” Commissioner Kuhn had held up the sale. The $500,000 purchase price exceeded the $400,000 player sale maximum that Kuhn had established in 1977.25 For two nights “they put me in (Yankee owner) George Steinbrenner’s condominium,” said Robinson and added that Tallis told him: “We don’t want you going near the ballpark. Here’s $500.”

Just before Kuhn held a hearing on the sale on February 16, Finley said the deal included Double-A pitcher Greg Cochran. Finley said Cochran’s price was $100,000, bringing Robinson’s value to the established $400,000 limit.26 Kuhn accepted the arrangement.

The Yankees had won the previous three A.L. pennants and the previous two World Series, but a surplus of left-handed hitting catchers was more relevant to Robinson. At the same time the team acquired Robinson they added left-handed hitting Brad Gulden. The team was also considering a promotion for Triple-A catcher Jerry Narron, also a lefty. Robinson calculated that, “Had I stayed in Oakland, I could have stayed below the radar…and gotten one year, two years, three years and been established,” he said. Despite New York’s winning tradition, the media spotlight, and the organization’s resources, Robinson said, “The worst thing that ever happened to me was being sold to the Yankees.”

Robinson began the 1979 season in Triple-A Columbus, sharing the catching with Gulden. (Narron started the season in New York.) Since college, Robinson had coped with slow starts as a hitter, and “I got off to another typically horrid start.” By midseason Robinson was hitting well, but his early struggle had left an impression on the front office. When catcher Thurman Munson died in an air crash on August 2, Gulden was called up instead.

The Clippers, with Yankee talent stockpiled in the minors, was “like a major league team,” said Robinson. Dave Righetti joined the team in mid-season. “Columbus was a great atmosphere,” Righetti said. “The place (Cooper Stadium) was packed every night. We used to outdraw major league teams.”27 The Clippers’ popularity transformed some players into local celebrities. One national men’s pants company hired Robinson and teammates Greg Cochran and Dennis Werth to appear in a baseball-themed photo ad in the Columbus Sunday Dispatch magazine.28

During 1979 Robinson also realized the importance of protecting his right throwing arm and shoulder if he wanted to get called up to the Yankees. A catcher’s chest protector had a fixed flap protecting the non-throwing left shoulder but Robinson observed there was no flap to protect a catcher’s right shoulder because it would restrict a catcher’s throwing movement. The absence of a flap exposed the right shoulder to foul tips and trauma to bone and muscle. “If you put your finger on that bone and you imagine a ball coming at you at 100 mile per hour off a bat, you’re going down,” said Robinson.

Determined to protect himself, Robinson took a catcher’s chest protector and cut out a semi-circle about four inches wide. Using an awl, he punched three holes at the base of semi-circle. He then threaded shoelaces through the holes and three corresponding holes at the top right corner of his chest protector to create a hinged vertical flap that would cover the front of his right shoulder but would not restrict his throwing. He had created the “Robbypad.” The device worked and other International League catchers endorsed the concept. Robinson began work with an attorney to research commercial patent protection of his invention.

The 1979 Clippers finished first in the regular season and won the International League championship. In 102 games Robinson hit .250 with nine home runs and 45 RBIs. Righetti said Robinson was “always athletic, with a good-looking swing, a cerebral catcher.” Robinson, along with the Robbypad, was called up to New York in September. He played in six games, with 12 at bats and two hits.

In 1980 Robinson got the nod over Gulden in Columbus.29 The Robbypad also kept Robinson’s shoulder safe, as he threw out 60 percent of runners trying to steal.30 The Clippers finished first and won the International League championship, becoming the first team in over 40 years to win consecutive titles.

Patent protection for the Robbypad was not as successful. During the season Robinson’s attorney advised that the Robbypad was probably not patentable, as similar sports protective devices had been previously granted patents. In the spring of 1981, however, baseball equipment manufacturer Wilson approached Robinson to suggest a possible financial arrangement. They met with Robinson during spring training in Fort Lauderdale, took pictures of the Robbypad and asked for detailed information. After more than a year Wilson decided it was no longer interested.

Patent protection for the Robbypad was not as successful. During the season Robinson’s attorney advised that the Robbypad was probably not patentable, as similar sports protective devices had been previously granted patents. In the spring of 1981, however, baseball equipment manufacturer Wilson approached Robinson to suggest a possible financial arrangement. They met with Robinson during spring training in Fort Lauderdale, took pictures of the Robbypad and asked for detailed information. After more than a year Wilson decided it was no longer interested.

Without a patent, and despite the brush-off by Wilson, the Baseball Hall of Fame was nevertheless interested in Robinson’s invention. It requested one of the Robbypad prototypes for an exhibit and its permanent collection on the evolution of catcher’s equipment.31 When he was pitching coach for the Giants Righetti also recalled the Robbypad. “I remember (catcher Buster) Posey getting hit in the shoulder and I said, ‘You should have had a Robbypad,’” Righetti said. 32

In 104 games during the 1980 season Robinson hit .240 with 12 home runs and 48 RBIs. The Clippers finished first and won the International League championship, becoming the first team in over 40 years to win consecutive titles.

As 1981 began, it appeared Robinson would be the back up to Rick Cerone, the Yankees’ starting catcher. 33 Gene Michael, who had managed Robinson in Columbus in 1979, was now the Yankees’ manager. A few months earlier, as General Manager, Michael had released catcher Johnny Oates and traded Gulden. Robinson was also out of minor league options, so if he was sent down then recalled he could be claimed by another team for $25,000. 34

At spring training, however, there was a new problem. The previous summer Robinson was in a car accident.35 He and Righetti, who shared an apartment, were coming home from a road trip in Robinson’s van on Broad Street in Columbus. “It was three or four in the morning,” said Righetti. “We pulled into the left-hand turn lane and the guy behind us must have been so drunk he was just following lights.”

Robinson estimated they were hit at 50 miles per hour. “The car the kid was driving was an accordion,” said Righetti.“The van, thank God. It saved us.” Righetti was not hurt, but Robinson was whiplashed when his seat back dislodged and was bent at a 45-degree angle.

After resting for five days, Robinson played again but shoulder and arm pain forced him to stop taking infield. “I didn’t let anyone know,” said Robinson, theorizing it would heal in the off season. He saw doctors, chiropractors and tried acupuncture. “My arm wouldn’t get better,” he said “but I didn’t want to tell them…I couldn’t push buttons on the car radio without hurting my arm.”

At the Yankees’ first 1981 spring training game the players’ union leadership was in attendance. Robinson told General Counsel Donald Fehr about his injury. Robinson said Fehr told him, “‘You’ve got to tell them you’re hurt. If you don’t, you’re not going to perform and they’ll send you down and you’re screwed.”’

When Robinson told the Yankees, they questioned the injury. “They were trying to tell me I was healthy so they could send me down,” said Robinson. “But why would I be faking when this is my first legitimate chance to stay in the big leagues,” he said.36 The stalemate continued into April as Robinson played five rehabilitation games with Single-A Fort Lauderdale. His shoulder still ached. When he asked permission to see well-known orthopedic surgeon Dr. Robert Kerlan in California, the Yankees denied the request, stating that the union contract limited team-paid second medical opinions to organization’s geographic region. When Robinson said he would cover the cost to see Kerlan, the Yankees agreed.

Kerlan determined that the shoulder had torn cartilage and a bone fracture. After his diagnosis showed that the injury had been aggravated by playing baseball, the Yankees accelerated Robinson’s surgery date and provided a hospital suite with a pull-out bed and a five-star catered meals for his fiancée.37

His arm and shoulder did not recover during 1981. Robinson missed the season, but his disabled list status allowed him to collect his full season salary of $45,000. Meanwhile, all other active union members went unpaid during the 50-day players strike. His disabled list status also generated full Yankee playoff and World Series shares totaling about $40,000. Plus, “I got half meal money every time they (the Yankees) went on the road even though I was home in La Jolla,” said Robinson. “That was my biggest (salary) year.”

In 1982 Robinson played in only 15 games in Columbus because his shoulder was still impaired. During the off season he married Barbara Oclassen, whom he had met in La Jolla after the 1980 season. The following spring, after being assigned to Columbus, he was released. After a few weeks at home he was signed by the Pirates and sent to Honolulu, one of minor league baseball’s most exotic locations. He and Barbara lived a few blocks from Waikiki Beach. Robinson played 58 games for the Hawaii Islanders, the Pirates’ AAA team.

In 1984 at age 30, Robinson was a six-year minor league free agent looking for a new major league opportunity. He found it in Oakland, where he hoped he could become a backup catcher for the A’s. “I could play about three days in a row before my arm started to fade,” he said.

When he signed with Oakland, Mike Heath was the A’s only catcher, but the team traded for veteran catcher Jim Essian and then added designated hitter candidates.38 Without space on the roster for a third catcher the A’s sent Robinson to Triple-A Tacoma, and promised that he would be called up if the Athletics needed a catcher.39

In June, the team offered the same call-up assurance when they asked Robinson to return to Single-A Modesto where he had started nine years ago, this time as a player-coach. Robinson said Minor League Director Karl Kuehl told him, “We want you to work with a struggling young player whose mother has died and we need someone fresh to work with him, and maybe you can think about a coaching role going forward.”

When Robinson arrived in Modesto, with his wife and eight-month old son Scott, he worked as a hitting coach for 20-year old Jose Canseco. Robinson said Canseco would say, “‘I need to get bigger’ and I’d say, ‘No, you need to stop pointing the end of your bat at the pitcher.’”

In August, Robinson was asked to coach Mark McGwire, who joined the team after the Olympics. Robinson took video of the developing stars, and together they watched tapes of their hitting on the VCR in Robinson’s apartment.

While at Modesto, Robinson was excited to hear that the Athletics needed a third catcher in Oakland, but the news soured quickly. “It was one of the more demoralizing moments of my life,” he said. General Manager Sandy Alderson informed him, ‘“We want to be the first ones to tell you that we’re not calling you up.”’

In the fall, the Athletics asked him to continue coaching, so he did off-season instructional work, helping to convert Terry Steinbach from a third baseman to a catcher. But after two weeks Robinson decided to return to San Diego with his family. At a career crossroads, “It was time for God to show me that good stuff can come from bad stuff,” said Robinson.40

At home in San Diego Robinson worked in commercial mortgage banking, real estate development and financial modeling, then moved on to the video game industry in the Silicon Valley. He returned to San Diego and worked in executive recruiting, then finished his very successful career with a leader in the technology market intelligence arena. His success enabled him to retire at 49. He has since split his time between San Diego and Idaho, where he bought a home on the Snake River in 2000.

In addition to son Scott, he and his wife Barbara had a daughter Kelly and a son Tommy. “All my kids hit left and threw right,” said Robinson. Scott played eight years of professional baseball.41 He worked in construction management. Kelly worked at home with her four children. Tommy played one year of college baseball and pursued a career in public safety.

Robinson and Barbara were divorced in 1998. Nine years later he was reunited with a kindergarten classmate, Pam Weber. In 2017 they were married. Impressed by his music, Pam encouraged Bruce to write his own songs and perform live for the first time since his childhood. He began to do both in 2008, giving new life to his love of music. By 2019 he had released 50 songs on three original CDs. In 2020 he released another CD with 23 more original songs. He fine-tuned his live show, leading to a performance at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

Robinson had met Rock and Roll Hall of Development Director Greg Harris in the mid-1990s when Harris held the same position at the Baseball Hall of Fame.42 In 2012 when Harris was booking live music for the main stage during public hours he invited Robinson to play a 90-minute set.

At 65, Robinson remained intensely competitive. “I hate to lose,” he said, noting his participation in regional and national pickleball senior pro (50+) tournaments.43 Pickleball is a two-to-four player sport that includes elements of tennis, badminton, and table tennis. He won the Gold Medal in Men’s Singles 60-64 Pickleball at the Idaho Senior Games in 2018 and 2019.

Reflecting on his baseball career, he recognized the impact of his 1980 car accident injury. “As my arm was my ticket (after the injury) I didn’t hit well enough to play third, first or corner outfield.”

Rene Lachemann, who managed Robinson for three years, agreed. “I thought he would be a 10- or 15-year veteran of major league baseball.”

Former teammate Brian Kingman, who became a lifelong friend, thought Robinson had the ability to be an all-star catcher. “As athletes we always think at some point you’ll be able to overcome this,” said Kingman. “Working out harder. Doing everything you possibly can, but some things you just can’t overcome. Baseball has very little patience because there are a lot of competitors come up through the ranks and the next thing you know you’re not playing anymore.”

But Robinson’s spirituality helped bring perspective to his baseball career. He said “Don’t think so much about the finish line as much as what you are supposed to be doing along the ride.”

Last revised: May 8, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Doutrich and David H. Lippman and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record and Robinson’s Hall of Fame file.

The author relied extensively on interviews with Robinson. Unless otherwise noted, comments from Robinson come from personal interviews on November 14 and 18, 2019, and follow-up email and text messages. Unless cited in these notes, comments from players and associates of Robinson listed below were obtained in telephone and email interviews.

Personal Interviews

Brian Kingman, telephone interview, November 24, 2019

Rene Lachemann, telephone interview, December 16, 2019

Dave Righetti, telephone interview, January 9, 2020

Allan Simpson, telephone interview, December 11, 2019 and January 17, 2020.

Notes

1 brucerobinsonmusic.com, http://www.brucerobinsonmusic.com/testimony.html, 7 minutes, 45 seconds, accessed January 13, 2020.

2 Mark McCarter, “Experience Helps Bruce Aid Lookouts Attack,” Chattanooga New-Free Press, June 12, 1977.

3 McCarter, “Experience Helps Bruce Aid Lookouts Attack.”

4 This quote and all others from Bruce Robinson come from interviews with him on November 14 and 18, 2019.

5 Based on Robinson’s personal baseball records, which he maintained from ages eight to 18, from Little League through High School; Bruce Robinson email December 16, 2019. His high school junior and senior batting averages were confirmed by newspaper stories in the San Diego Union and Evening Tribune.

6 Bill Finley, “La Jolla slugger catches pro eyes,” Evening Tribune, March 27, 1971, page unknown.

7 Bill Finley, “Forster, D’Acquisto gone but hope is present,” Evening Tribune, April 6, 1971, C-2.

8 Finley, “La Jolla slugger catches pro eyes.”

9 Baseball-reference.com, Dave Robinson page, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/robinda01.shtml, accessed January 13, 2020.

10 Thacher’s American Legion coach, Tom Dunton was the Stanford pitching coach. Dunton suggested to Stanford head coach Ray Young that he recruit Robinson.

11 Bill Finley, “Viking catcher chips in — in one swing,” Evening Tribune, March 18, 1972, B-1.

12 Bill Finley, “Scouts rate area prospects for draft,” Evening Tribune, June 3, 1972, B-1.

13 The Goldpanners Head Coach was Jim Dietz, head baseball coach at San Diego State. Robinson had been offered a full scholarship to San Diego State by Dietz. Four years earlier, in 1968, Robinson’s brother Dave had won his second consecutive team MVP at San Diego State. He was the first player signed by the expansion San Diego Padres in 1969.

14 panneralumni.com, http://www.panneralumni.com/gp2mlb-by-season/, accessed January 13, 2020.

15 Robinson hit four home runs in the eight-game tournament, and was named to the All-Tournament team.

16 Instead Robinson maximized his course load and took sixty-four credits his junior year, so he would need only 18 more to graduate. He completed those 18 hours after his first year at Modesto. He said he was motivated by the struggle of his older brother Dave, who was forced to manage the competing demands of work and family when he left baseball at the age of 25 and needed to complete his senior year of college

17 According to Robinson, he played guitar with the band “Nau and Them,” led by keyboard player Jim Nau. They performed Herman’s Hermit songs “I’m Henery the Eighth” and “Mrs. Brown You’ve got a Lovely Daughter.

18 Dick O’Connor, “Robinson’s Debut,” Palo Alto Times, August 22, 1978, page unknown.

19 At the end of the 2019 season Baseball Almanac reported the total to be 414. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/family/fam1.shtml, accessed January 13, 2020.

20 Other pitchers were Mike Torrez, Al Hrabosky and Dennis Martinez.

21 Team average was 42% according to baseball-reference.com. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/OAK/1979-fielding.shtml, accessed January 13, 2020.

22 The Supreme Court refused to hear Finley’s appeal of a U. S. Court of Appeals decision that upheld Kuhn’s voiding of 1976 cash player transaction. Kuhn had voided the sale of Rollie Fingers and Joe Rudi to the Red Sox for $2 million and Vida Blue to the Yankees for $1.5 million.

23 Left-handed hitting catchers being considered for playing time were Jerry Narron, who played for the Triple-A Tacoma Yankees in 1978, Brad Gulden, obtained in a trade with the Los Angeles Dodgers on February 15, and Robinson.

24 This is the date of the original transaction, according to Retrosheet. https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/R/Probib102.htm, accessed January 13, 2020.

25 Murray Chass, “Kuhn Upholds Sale of 2 A’s to Yankees”, New York Times, February 17, 1979, 9. In 1977 Kuhn allowed the sale of Athletics pitcher Paul Lindblad to the Texas Rangers for $400,000.

26 Chass, “Kuhn Upholds Sale of 2 A’s to Yankees.”

27 In 1979 the Clippers attendance was 599,544, more than the Oakland Athletics attendance of 306,763. (http://www.thebaseballcube.com/minors/teams/history.asp?T=10147), accessed January 13, 2020. Based on 70 home dates (which is probably high due to doubleheaders) the Clippers average attendance of was 8,564, and for some games probably exceeded attendance of MLB franchises such as Atlanta (average attendance of 9,740) and the Mets (average attendance of 9,621), https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/1979-misc.shtml, accessed January 13, 2020.

28 The Columbus Daily Dispatch Magazine, May 27, 1979, page 32

29 Gulden had 60 at bats in Columbus before he was sent to AA Nashville, according to baseball-reference.com.

30 Mark Stadler, “Local ballplayer fights big league injury jinx,” La Jolla Light, July 23, 1981, C-3. Robinson said he typically had a caught stealing rate of more than fifty percent, Robinson e-mail correspondence, December 20, 2019.

31 Robinson donated one of his 1980 Robbypad prototypes to the Hall of Fame in 1995.

32 Righetti was the Giants pitching coach from 2000 to 2017.

33 Murray Chass, “Michael Surveys Crowded Field” New York Times, March 9, 1981, p. 39.

34 Keith Olson, “Robinson on Rise with Yankees,” Daily News-Miner, November 29, 1980, page 14.

35 Robinson does not recall the exact date. He believes it was late July or early August.

36 Mark Stadler, “Local ballplayer fights big league injury jinx,” La Jolla Light, July 23, 1981.

37 The surgery was performed by Dr. Frank Jobe and required the permanent placement of a large surgical “T” staple to support the shoulder bones and connective tissue.

38 Dave Kingman and Jeff Burroughs were added in December, 1984.

39 Bruce Robinson Interview, November 18, 2019.

40 brucerobinsonmusic.com, http://www.brucerobinsonmusic.com/testimony.html (accessed January 13, 2020), 31 minutes, 30 seconds.

41 Scott Robinson graduated from Rancho Bernardo High School in San Diego and was drafted by the Houston Astros in the 7th round of the 2002 amateur draft. Most of his eight-year minor league career was with the Houston Astros. He was an ambidextrous thrower. His father said in one professional game he played first base left-handed and then caught, throwing out a base runner right-handed.

42 While on an extended business trip to New York City in the mid-1990s, Robinson visited the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. When he brought to the staff’s attention some display description errors, he was introduced to Harris to review what he found.

43 He played in eight tournaments in three years, according to player look up records at Pickleball Tournaments.com, https://www.pickleballtournaments.com/pbt_main.pl., (accessed January 13, 2020), including two prize money winning 4th place finishes in singles and doubles in a senior pro tournament.

Full Name

Bruce Philip Robinson

Born

April 16, 1954 at La Jolla, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.