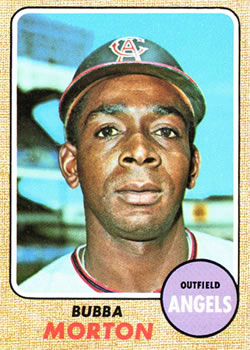

Bubba Morton

Bubba Morton spent parts of seven major-league seasons between 1961 and 1969 as a platoon outfielder and pinch-hitter with the Detroit Tigers, Milwaukee Braves, and California Angels. He was a spray hitter with occasional pop, had a penchant for getting on base, and played excellent defense. Don Mincher once called him “the perfect teammate.”1 Morton broke ground as a minor leaguer, becoming the first African American player with the Durham Bulls. He later did the same in the college coaching ranks at the University of Washington.

Bubba Morton spent parts of seven major-league seasons between 1961 and 1969 as a platoon outfielder and pinch-hitter with the Detroit Tigers, Milwaukee Braves, and California Angels. He was a spray hitter with occasional pop, had a penchant for getting on base, and played excellent defense. Don Mincher once called him “the perfect teammate.”1 Morton broke ground as a minor leaguer, becoming the first African American player with the Durham Bulls. He later did the same in the college coaching ranks at the University of Washington.

Wycliffe Nathaniel “Bubba” Morton was born on December 13, 1931, in Washington, D.C.2 He was named after his father, Wycliffe Francis Morton, who worked as a porter. His mother was the former Mary Madaline Page. Bubba, who acquired his nickname at a young age, attended Armstrong High School in the nation’s capital. On a 1958 publicity questionnaire, he indicated that he did not play any sports in high school, but later described to a reporter how he helped Armstrong’s baseball team to a championship his junior year and became ineligible to play his senior year because he signed a professional contract.3,4

After graduating from Armstrong in 1949, Morton enlisted in the United States Coast Guard and served for four years as a radio operator.5 When he completed his military service, he enrolled at Howard University, where he majored in engineering and lettered in football and baseball. He batted .340 as a freshman at in 1954, his lone season with Howard.6 He also played for a time with a D.C. amateur club called the Aztecs.7

In March 1955, Tigers scout Pete Haley signed Morton as an amateur free agent. He was the third African American signed by the team, following Claude Agee and Arthur Williams. Morton was assigned to the Idaho Falls Russets of the Class D Pioneer League, where he served as the team’s center fielder and showed the potential of a five-tool player. In 130 games, he hit .247 with 10 homers, 77 runs batted in, and 18 stolen bases.

Morton, who both threw and hit right-handed, began the 1956 season with the Terre Haute Tigers in the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League. He saw time at both third base and the outfield, hitting .239 with three homers in 47 games. On June 26, Morton was optioned to the Class D Jamestown Falcons in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League.8 He performed well following the demotion, hitting .324 with nine homers in 63 games as an outfielder and first baseman.

Morton spent 1957 with the Bulls, then of the Class B Carolina League. When he and starting pitcher Ted Richardson took the field on Opening Day, they became the team’s first African American players. Morton led the team in batting average (.310), on-base percentage (.413), slugging percentage (.521), runs (93), and stolen bases (18). He made the league’s All-Star team and helped the Bulls to their first league championship.

While Morton stood out because of his performance on the field for Durham, he stood out off the field because of his skin color. He faced segregation throughout the Southern League circuit and had to stay in private homes on road trips because hotels did not accommodate Black players. But he had the support of his teammates. “I’ll tell you what kind of teammates I had in Durham – they wouldn’t go and eat in a restaurant without me,” Morton recalled in 1997. “Somebody would always go in and get sandwiches for everybody, then they’d bring them to the bus, and we’d go on our way.”9

That offseason, Morton played winter ball with the Mexico City Reds of the Double-A Mexican Baseball League. Except for two games with the Triple-A Charleston Senators, he spent the 1958 season with a pair of Single-A teams – the Augusta (Georgia) Tigers in the South Atlantic League and the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses in the Eastern League. With Augusta, Morton hit .254 with two home runs in 39 games. After being reassigned to Lancaster, managed by Johnny Pesky, Morton competed for the league’s batting title and made the league’s All-Star squad. With the Red Roses, he batted .323 with a .424 OBP and hit two homers in 94 contests.

Morton was assigned to Charleston in 1959 and spent the entire season with the American Association club. The outfielder produced a triple slash line of .285/.350/.384, homered twice and stole eight bases. In 1960, the Tigers changed Triple-A affiliates to the Denver Bears of the American Association. Morton, at age 28 and in his sixth season of professional ball, remained one step away from the major leagues. “He probably doesn’t fit into Detroit’s outfield plans because he does not hit many homers,” wrote Frank Haraway of The Sporting News.10 While not a power hitter, the 5-foot-10, 175-pound Morton displayed an ability to impact the game in other ways. After 101 games, he was hitting .334 and competing for the league’s batting title.11 Morton finished the season at .296 while homering nine times and driving in 66 runs as the team’s stalwart left fielder and leadoff man. He also broke the team record with 30 stolen bases.12

By 1960, Black players were still not allowed at the team hotel in Louisville (Kentucky), site of another American Association team. That changed one day thanks to Denver manager Charlie Metro, who recounted the story in his memoir Safe by a Mile. When the Bears were checking in the hotel, Morton and the team’s two other Black players, Ozzie Virgil and Jake Wood, went to leave because of the hotel’s policy. Metro insisted the clerk check his black players in. When the clerk refused, the skipper grabbed him by the collar. Police showed up and Metro spent the night in jail, but his players got to stay at the hotel from that point forward.13

Morton played winter ball in 1960 with the Valencia Industrialists in the Venezuelan Association. Through the first four weeks of the season, he carried an eye-popping .537 average.14 In one contest, the speedster hit inside-the-park home runs in consecutive at bats. He even filled in at catcher after the team’s regular backstop fractured an ankle. Morton won the league’s batting title with a .389 average.15 Among his competitors was a young pitcher from the Cardinals named Bob Gibson.

In 1961, Morton arrived at Tigers spring training in Lakeland (Florida) with, as one writer from The Sporting News put it, “as much chance of sticking as a piece of stale gum.”16 However, the non-roster invitee picked up where he left off in Venezuela and soon had the attention of sportswriters and team brass. His combination of hitting, speed, and defense drew comparisons to Minnie Miñoso, and one sportswriter called him “the most exciting player in camp.” When asked if Morton had a shot to be the sixth outfielder, manager Bob Scheffing said, “If he keeps hitting this way, he could be my third outfielder.”17 Morton did not supplant Al Kaline, Rocky Colavito, or Bill Bruton, but he made the Tigers’ opening day roster as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter. He was helped out because George Alusik, another outfield prospect with more power, held out in a salary dispute.

Morton made his major-league debut on April 19, becoming the eighth person of color to play for the Tigers, when he pinch-ran for Charlie Maxwell. Bubba collected his first hit on April 30, an RBI single off Steve Barber. With the regulars rarely taking a day off, Morton was limited almost exclusively to a bench role for the first half of the season, only starting twice. He made the most of his rare opportunities, however. The rookie drove in five runs in the two starts, including his first career home run on June 4 versus Twins starter Jim Kaat.

Morton received more playing time in the second half of the season and performed well down the stretch. He delivered game-winning pinch-hit RBIs in consecutive games against the Red Sox on August 19-20. The first of those came when he was called on to hit with a 2-2 count for Dick McAuliffe, who had failed to get down a sacrifice bunt.18 In September and the season finale on October 1, Morton went 13-for-36 for a .361 average. His finished the season hitting .287 in 108 at bats. The Tigers won 101 games but finished eight games behind the mighty Yankees.

In 1962, Morton again filled the role of reserve outfielder and bench bat for the Tigers. He made only 19 plate appearances in the team’s first 49 games. When Kaline suffered a fractured clavicle on May 26 and Bruton pulled a muscle on June 10, the door was open for Morton to see more regular playing time, particularly against southpaws. In just his second start of the season on June 8, Morton went 4-for-6 against the Senators. For the season, he hit .262 with a .366 on base percentage and four homers in 195 at bats. After the season, the Tigers made a 21-game exhibition tour through Hawaii, Korea, and Japan. Morton received regular playing time in place of Colavito and led the team in batting average .366 (26-for-71) with three homers.19

Morton began the 1963 season with the Tigers but saw sparse playing time and went 1-for-11 in 20 games. On May 4, Detroit sold Morton’s contract to the Braves for cash. Milwaukee was winless in seven games against lefty starters and hoped his right-handed bat would bolster the offense. However, Morton hit just .179 (5-for-28) in 15 games with Milwaukee. In his brief tenure with the Braves, he roomed with Henry Aaron. On June 17, Morton was optioned to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. Back in the minors for the first time in three years, he produced a slash line of .280/.373/.462 with nine homers in 79 games.

Morton was traded from Toronto to the Denver Bears in January 1964. Denver had become the Braves’ other Triple-A affiliate and joined the Pacific Coast League. The 32-year-old veteran hit .303/.390/.454 with nine homers and 79 runs batted in. Morton played with the Braves’ Florida East Coast Instructional League that winter and hit .190 in 36 games.

In 1965, Morton played outfield for the Portland Beavers, Triple-A affiliate of the Cleveland Indians. Through August 8, he led the league in batting with a .352 average.20 He finished the campaign with a .319 average, eight homers and 50 runs batted in from the leadoff spot. Following the season, Portland sold Morton’s contract to the Seattle Angels.

When it came time for players to report to camp with the Angels in 1966, Morton was a no-show. His wife, the former Audrey Farrar, had obtained a well-paying job in Denver during the off-season, and he had grown frustrated with being moved from team to team. Bubba himself had other career options – he had obtained a job as an engineer making Bell telephone equipment for Western Electric, an off-season position he would hold for six years.21 “I was ready to quit in disgust,” Morton said in retrospect. “The Angels were my third organization in three years.”22 After some convincing by Seattle general manager Edo Vanni and California assistant general manager Marvin Milkes, Morton reported to camp.23 Morton played right field and hit .286 with 10 home runs and 60 RBIs. Seattle defeated Tulsa, managed by Metro, to win the PCL championship. After the series, Morton was among the September callups to California. He started 14 of the Angels’ final 18 games and hit .220 (11-for-50).

Morton led the Angels in runs batted in during spring training of 1967 and made the opening day roster.24 However, he made only one start and 14 plate appearances in the team’s first 22 games before being sent back to Seattle at the May roster cutdown. He carried a .239 batting average and swatted four homers in 24 games with Seattle. “I was hitting well, but nothing was falling in,” Morton said.25 He was recalled to the parent club on June 1.

Angels manager Bill Rigney utilized Morton in a platoon with Jimmie Hall. The 34-year-old Morton enjoyed the most success of his big-league career through the rest of the 1967 campaign. He mostly started against lefties, but he actually hit better versus righties (.333) than southpaws (.304). The well-traveled veteran, often described as quiet or soft-spoken, was content with his role. “I’m in no position to make demands,” he said at the time. “I accept what the situation dictates.”26 Morton was scorching hot in August, when he hit .417 (19-for-46) with three doubles and two triples. In a September 5 doubleheader sweep of Baltimore, he drove in eight runs. He finished the season without a home run but had an impressive .313 batting average and 32 RBIs for the fifth place Halos. Despite his lack of power, he had an OPS+ of 132 because of his excellent .387 OBP.

Morton spent the entire 1968 season with the Angels as a spare outfielder and pinch-hitter. All but one of his 39 starts were against left-handed pitchers. His lone home run came against Tommy John on May 6. Morton remained a reliable pinch hitter (10-for-32) and hit .270 for the season in 184 plate appearances.

A players’ strike before the 1969 season resulted in players with four years of major-league experience, like Morton, receiving eligibility for a pension. The 37-year-old father of four said it was “the best news I’ve received in six months.”27

Morton maintained his familiar role with the Angels in 1969, his last year in the big leagues. He started 44 games, and though his batting average dropped off to .244, he maintained an OBP of .356, slugged seven home runs, and drove in 32 runs in 206 plate appearances. Morton continued his success against John, homering against the southpaw on June 20 and again on July 6. The latter shot traveled 420 feet through wind and mist to account for the Angels’ only runs in a 2-1 victory over the White Sox.28

Morton was assigned to Triple-A Hawaii following the ’69 season. He reached out to the Seattle Pilots about catching on for their second season in the league, but no deal came to fruition. The Pilots relocated to Milwaukee the following spring.

Morton’s marriage to Audrey resulted in four children: Michael, Michelle, Brian, and Brenda. They divorced in February 1970. Morton spent 1970 playing for the Toei Flyers in the Japan Pacific League. Toei outbid another Japanese team and made him a contract offer he could not refuse.29 He quickly discovered some differences between ball in Japan and the United States. Spring training was held in temperatures barely above freezing, and workouts stretched well into the late afternoon. “And there are no rainouts in Japan,” Morton explained to Hy Zimmerman of the Seattle Daily Times. “On days you get rained out, the team will work out for hours under the stands or go round and round on a running track…but I liked it, liked the people.”30 In 48 games, he made 94 plate appearances and hit only .173. That marked the end of his professional baseball career. Morton retired from the major leagues with 248 hits, 14 homers, a batting average of .267, and an OBP of .351 in 451 games.

Following his baseball career, Morton settled in Seattle, a city he had come to love from his time with the Triple-A Angels. He took a job at the Madison YMCA. and in the security division at the University of Washington, and then was named athletic director of boys’ sports at the Bush School in May 1971. Morton remarried on September 23, 1971, to Washingtonian Anne Pearlman.

In December 1971, Morton was hired to coach the University of Washington’s baseball team, succeeding Ken Lehman, who had stepped down earlier in the year. Morton was the university’s first African American head coach, a position he held for five years. During his tenure, scholarships were limited due to financial reasons, contributing to a record of 48-101 from 1972-76.31

Following his coaching career, Morton worked as an engineer at Boeing and was a reservist with the Coast Guard. He died in Seattle on January 14, 2006, at the age of 72 after an extended illness and was buried at sea.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf, Tony Oliver, and Rory Costello, and fact-checked by Paul Proia. Thanks to Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Research Committee, for scouting information.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Larry Stone, “Former UW Coach Morton Dies at 74,” Seattle Times, January 18, 2006: D3.

2 Baseball-Reference and other sources list his birth year as 1931, but several other sources, including U.S. Social Security Claims, the Social Security Death Index, and publicity questionnaires list his birth year as 1932.

3 “Morton, Star with Big Angels, Can’t Forget Long Minor Stretch,” Seattle Daily Times, March 12, 1968: 28.

4 William J. Weiss Publicity Questionnaire, January 13, 1958.

5 Weiss questionnaire.

6 “Bison Signed,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1955: 13.

7 Weiss questionnaire.

8 Bill Shores, “Shore Shots,” Terre Haute Tribune, June 27, 1956: 14.

9 Stone.

10 Frank Haraway, “Outfield Dandy Finds a ‘Home’ with Denverites,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1960: 29.

11 Haraway.

12 Haraway.

13 Charlie Metro with Thomas Altherr, Safe by a Mile, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002): 244.

14 Sam Solana, “Morton Mauling Twirlers as Top Velencia Socker,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1960: 43.

15 Rodolfo Gutierrez, “Gibson and Bracho Twirl Velencia to Playoff Title,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1961: 17.

16 Joe Falls, “Bubba’s Torrid Bat Sets Off Fireworks in Bengals’ Garden,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1961: 21.

17 Falls.

18 Watson Spoelstra, “Kids and Castoffs Doing Bangup Job as Bengal Spares,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1961: 2.

19 Lee Kavetski, “Salvo of Cheers Caps Windup of Bengal’s Junket,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1962: 30.

20 “Bubba Morton Leads PCL in Hitting,” Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph, August 11, 1965: 18.

21 “Bubba Morton now Playing Baseball in Tokyo, Japan,” Brainerd Daily Dispatch, August 18, 1970: 9.

22 Hy Zimmerman, “SeAngels Likely to Regain Kirkpatrick,” Seattle Daily Times, March 22, 1967: 71.

23 Hy Zimmerman, “Reluctant Outfielder Decides to Check In,” Seattle Daily Times, March 28, 1966: 13.

24 Hy Zimmerman, “CalAngels Recall Bubba Morton,” Seattle Daily Times, June 1, 1967: 37.

25 Ross Newhan, “Bubba Enjoying Heavenly Days in Angel Garb,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1967: 17.

26 Newhan.

27 Gordon Verrell, “37-Year-Old Bubba Reaps New Benefits,” Press-Telegram (Long Beach, California), February 26, 1969: 34.

28 “Halos in Seattle, After ChiSox Win,” Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California), July 7, 1969: 16.

29 “Bubba Morton now Playing Baseball in Tokyo, Japan.”

30 Hy Zimmerman, “Wycliffe Back, and Welcome,” Seattle Daily Times, February 16, 1971: 18.

31 Stone.

Full Name

Wycliffe Nathaniel Morton

Born

December 13, 1931 at Washington, DC (USA)

Died

January 14, 2006 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.