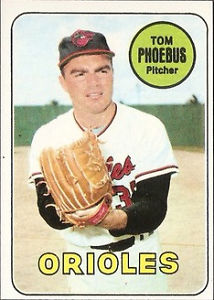

Tom Phoebus

American League batters in the late 1960s often cited the 5-foot-8, 185-pound Tom Phoebus as one of the toughest pitchers to hit against. According to The Sporting News, Phoebus possessed an imposing arsenal of pitches: a good fastball; a slider with the break of a curveball; and a “ridiculous” curveball. Phoebus’s primary pitching challenge was consistent control; he was characterized as sometimes having “too much stuff.”1 He pitched professionally from 1960 to 1973, winning 56 major-league games, including 50 for his hometown Baltimore Orioles. In 1970 he had a 5-5 record and won the second game of the World Series for the Orioles in relief.

American League batters in the late 1960s often cited the 5-foot-8, 185-pound Tom Phoebus as one of the toughest pitchers to hit against. According to The Sporting News, Phoebus possessed an imposing arsenal of pitches: a good fastball; a slider with the break of a curveball; and a “ridiculous” curveball. Phoebus’s primary pitching challenge was consistent control; he was characterized as sometimes having “too much stuff.”1 He pitched professionally from 1960 to 1973, winning 56 major-league games, including 50 for his hometown Baltimore Orioles. In 1970 he had a 5-5 record and won the second game of the World Series for the Orioles in relief.

Born in Baltimore on April 7, 1942, Thomas Harold Phoebus grew up on Fawcett Street within two miles of the site of Memorial Stadium, which was completed in 1950. As a child, he played baseball in his neighborhood Catholic Youth Organization League.2 From 1956 to 1959, Phoebus attended Mount Saint Joseph High School, playing fullback on the football team and pitching for the baseball team. As a senior he pitched a no-hitter, striking out 15 hitters.3 (In 1985 Phoebus was inducted into the Mount Saint Joseph Hall of Fame.)

After graduating in 1960, the 18-year-old Phoebus signed with the Baltimore Orioles for a $10,000 bonus. He had been recommended to the Orioles by scouts Arthur Ehlers, Fritz Maisel, and Walter Youse. For Orioles fan Phoebus, playing for his hometown team was the realization of a childhood dream. “As kids,” he later reflected, “we would go to the (Orioles) games, sit in the bleachers for 50 cents and ride the right fielder for the opposing team.”4

With the Bluefield (West Virginia) Orioles in the rookie Appalachian League in 1960, Phoebus pitched 91 innings in 18 games and compiled a 6-5 record. In 1961 he pitched for Leesburg (Florida) in the Florida State League (Class D). He suffered the worst year of his professional career, pitching in 34 games and compiling a 1-12 record for the last-place team with a 5.56 earned-run average (he walked 98 batters in 81 innings). Despite this setback, the Orioles pushed the 20-year-old up to Aberdeen (South Dakota) in the Class C Northern League, and the results were much better. For the Pheasants, Phoebus finished 13-10 with a 4.47 ERA and a league-leading 195 strikeouts. His 152 walks in 167 innings suggest that he did not always know where the ball was going.

In 1963 Phoebus pitched for the Elmira (New York) Pioneers in the Double-A Eastern League. In this advanced league, he pitched in 29 games and 175 innings, and posted a 12-7 record with a 3.03 ERA. He walked 124 and struck out 212, which broke the club record for strikeouts. At Elmira Tom pitched for Earl Weaver, for whom he would pitch in the major leagues. After the season, the Maryland Professional Baseball Players Association selected Phoebus as Maryland’s “star of the future.”5 He later called the award one of the highlights of his early professional career.

For the next three seasons, beginning in 1964, Phoebus pitched for the Orioles’ highest affiliate, the Rochester (New York) Red Wings of the International League. In 1964 he pitched in 30 games, finishing 11-9 with a 3.39 ERA. Rochester finished fourth in the regular season, but won two rounds of playoffs to capture the league title. Phoebus started a won a game in each playoff round.6 The next season he slipped to 8-8 in 23 games for a fifth-place club. “He’s the kind of kid who gives you ulcers,” said George Sisler Jr., then the Rochester general manager. “He’s always in and out of hot water. You always have the impression it’ll be a tough game. Then you look up in the seventh inning and Tom is still out there pumping and we’re usually ahead.”7

Phoebus had high expectations for his 1966 season going into spring training. “I wanted to make (the Orioles) more than anything in the world,” he remembered. His hope turned to disappointment; he had a good spring training only to be reassigned again to the Red Wings. The Orioles had continuing concerns about his control, particularly keeping the ball down. Phoebus regrouped and finished 13-9 while posting fine marks in complete games (14), shutouts (5), innings pitched (200), strikeouts (a league-leading 208), and ERA (3.02), and pitching a no-hitter. With Weaver at the helm, the 1966 Red Wings won the regular-season title but lost in the first round of the playoffs.

His no-hitter, on August 15, was a 1-0 gem in seven innings, the first game of a doubleheader at home against Buffalo. Phoebus struck out seven and walked two. He helped save his no-hitter by knocking down a potential ground-ball hit barehanded and throwing the batter out. The only other potential hit was an infield slow roller that resulted in a close, disputed out at first base. Phoebus relied on his curve and slider through most of the game, using the fastball only to complement his breaking pitches. Manager Earl Weaver was impressed. “It’s a beautiful thing to watch when the curve and the slider are working for him,” said Weaver.8

In late August, after the no-hitter, the Tom Phoebus Fan Club conducted a friendly protest in his old Baltimore neighborhood, urging the Orioles to call him up immediately. Primarily composed of his friends and neighbors and their young children, the small crowd carried signs such as “Give Tom Phoebus A Chance to Pitch.” In early September, Weaver summed up Phoebus’s status to The Sporting News. “He has major-league pitches. Everybody in the organization knows this. It’s just that he must prove that he can throw strikes consistently. …. Tom has a major-league fastball and slider right now. It’s his curve that he has trouble controlling. … I think he has an excellent chance to pitch for Baltimore next year”9

Phoebus and several other Red Wings players joined the Orioles in mid-September. The 1966 Orioles were destined to be the world champions but were currently on a four-game losing streak. “(There’s) nothing wrong with us that a few well-pitched games wouldn’t fix,” grumbled manager Hank Bauer. When Phoebus arrived, Bauer decided to start him immediately, telling him, “Just pitch like you did in Rochester.” For Phoebus it was his “homecoming,” his first opportunity to pitch for his childhood heroes.

After rain postponed his start for two days, Phoebus started the first game of a doubleheader against the California Angels on September 15 in front of 7,617 customers on a damp, chilly evening. Among the crowd were his mother, his younger brother, about 14 aunts, uncles, and other relatives, and many of his neighbors. Phoebus responded by pitching a complete-game shutout, beating Dean Chance, 2-0. He struck out eight, walked two, and allowed only four hits. As he fanned the last hitter, the fans gave him a standing ovation. After his triumph, Phoebus was immediately hailed by the Baltimore press as the new hometown hero. Phoebus was ecstatic. “If Tom’s post-game grin would have been any wider, reported the Baltimore Sun, it would have swallowed his ears.” Asked if the postponements had made him nervous, Phoebus responded, “I’ll say I was nervous. I’ve been nervous since Tuesday.” How did he deal with his nerves: “I just tried to relax around the house, listening to my brother’s stereo. Mostly, I listened to rock ’n’ roll.” He credited his defense with preserving his shutout. “They made some great plays. They were terrific behind me,” said Phoebus. “I just tried to throw strikes.” Orioles Personnel Director Harry Dalton, manager Hank Bauer, pitching coach Harry Brecheen, and catcher Andy Etchebarren all gave Phoebus the credit.10

Five days later Phoebus got his second start and pitched his second shutout. Pitching against Catfish Hunter in Kansas City, he blanked the Athletics 4-0. Phoebus became only the seventh pitcher since 1900 to pitch shutouts in his first two games.11 The streak ended in his next start, on September 26, when the Angels tagged Phoebus for seven hits and three runs in four innings and won, 6-1.12 Ineligible for the World Series, Phoebus watched from the dugout as the Orioles swept the Los Angeles Dodgers. In his brief debut he posted a record of 2-1 in 22 innings with a 1.23 ERA, striking out 17 and walking only 6.

Phoebus’s Maryland roots quickly made him a fan favorite. During the offseason, he reportedly filled nearly 30 speaking appearance requests, working them in around his offseason job as a draftsman. Convinced that his control problems were behind him, the Orioles began the 1967 season with Phoebus in their starting rotation. It was a bad season for the Orioles: a 76-85 record and a sixth-place finish. But Phoebus sparkled. He posted a 14-9 record with a 3.33 ERA. He started 33 games and pitched 208 innings. He led the pitching staff in innings pitched, games started, strikeouts, and victories. In late May and early June he pitched consecutive shutouts, against New York, Boston, and Washington, equaling the achievement of an earlier Orioles pitcher, Milt Pappas. The Sporting News picked Phoebus as the 1967 American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year.. After a courtship of three months, Phoebus married his wife, Susan, a Baltimore native.13

The 1968 season was a year of major transition for the Orioles. Although they finished second to the Tigers, with a 91-71 record, manager Hank Bauer was fired in midseason and Earl Weaver succeeded him. Phoebus posted a 15-15 record with career bests in games started (36), strikeouts (193), innings pitched (240⅔) and ERA (2.61). He pitched a no-hitter against the defending American League champion Boston Red Sox at Memorial Stadium on April 27. The night before, he had left the ballpark early with a sore throat. He talked with Bauer the next morning and they decided he would pitch as scheduled. Rain delayed the start of the game about 90 minutes. The contest began in a light drizzle in front of a small crowd of 3,147 paying customers and 11,568 scholastic safety-patrol youngsters. Phoebus struck out nine and walked three in the 6-0 victory. Two defensive plays saved the no-hitter. In the third inning Phoebus deflected a chopper off the tip of his glove. Shortstop Mark Belanger charged in, scooped the ball up, and threw the batter out. In the eighth third baseman Brooks Robinson lunged to his left and speared a line drive. For his achievement, the Orioles rewarded Phoebus with a $1,000 bonus.14

Phoebus started strongly in 1969, beginning with two shutouts. By the end of May, his record stood at 5-1 with a 3.79 ERA in 10 starts, and he settled in to finish 14-7 with a 3.52 ERA in 202 innings. With the acquisition of Mike Cuellar from Houston and the comeback from injury from Jim Palmer, Phoebus was no longer one of the top starters on the club. In fact, although he won the pennant-clinching game by beating the Cleveland Indians on September 13, he did not appear in either the playoff series against the Minnesota Twins or the World Series loss to the New York Mets.

For 1970 Phoebus faced stiff competition (Jim Hardin) for the fourth starting pitcher position, which they wound up sharing. Through July 27 Phoebus appeared 18 times, starting 14 games and relieving four times. He slumped in August and pitched infrequently, but rebounded to win a couple of September starts to finish 5-5 with a 3.07 ERA. In Game Six of the World Series, in Cincinnati, Phoebus relieved Mike Cuellar in the third inning with the Orioles losing 4-0. He got Lee May to ground into a double play to end the inning, then pitched a scoreless fourth. The Orioles scored five times in the top of the fifth to take the lead and won 6-5, making Phoebus the winner in his only World Series appearance.

In December 1970 the Orioles traded Phoebus and three other players to the San Diego Padres for pitchers Pat Dobson and Tom Dukes.15 Phoebus and his wife greeted the news with mixed emotions as both were Baltimore natives and had many friends and family members in the area. He soon realized the opportunity he had to resurrect his career in San Diego. “I couldn’t adjust to spot starting with the Orioles,” he said. “I want to start every day.” As for moving from a world championship team to the Padres, he remained positive. “It’s the desire to win that overcomes everything,” he said. “I believe it’s the biggest factor to be successful in the majors. And you have to have it every day.”16

But 1971 turned out to be worst year in the major leagues. He appeared in 29 games (21 starts) and posted a 3-11 record. He pitched 133⅓ innings, allowing 144 hits and finishing with a 4.46 ERA. After July San Diego used Phoebus exclusively as a reliever. In April 1972 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs for cash and a player to be named later. For Chicago he appeared in 37 games (just one as a starter), finishing 3-3 with a 3.78 ERA.

In November 1972 the Cubs traded Phoebus to the Atlanta Braves for struggling infielder Tony La Russa, later to win fame as a major-league manager. Phoebus he spent the 1973 season with the Braves’ Richmond club in the International League. He pitched 125 innings and posted a 7-11 record with a 3.38 ERA, not enough to earn him another chance in the major leagues. After the season he retired from baseball. He was 31 years old.

After baseball Phoebus moved to Florida, working first for a liquor distributor and then for Tropicana, the orange juice manufacturer. At the age of 39 he enrolled at Manatee Community College, and then at the University of South Florida, graduating with a degree in education. He spent nearly two decades as a physical-education instructor in three Florida grade schools before retiring. In 1991 Phoebus was inducted into the Maryland State Athletic Hall of Fame.

In his later years, he lived in Palm City, Florida, the father of two sons: Thomas, a high-school teacher, and Joseph, a computer graphic artist. Phoebus played golf regularly, but reported that his fastball has lost its “oomph.” “I can’t crank it up to 94 (miles per hour) anymore,” he lamented.

He died at the age of 77 on September 5, 2019.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Pitching, Defense, and Three-Run Homers: The 1970 Baltimore Orioles” (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), edited by Mark Armour and Malcolm Allen.

Notes

1 Phil Jackman, “Pat Dobson Acquired to Fill No.4 Spot on Oriole Staff,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1970, 38.

2 Walter L.Johns, “Orioles’ Tom Phoebus,” Cumberland News, March 24, 1967, 34.

3 “St. Joes Wins On No-Hitter,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1959, 23.

4 Mike Klingman, “Catching Up With Former Oriole Tom Phoebus,” Baltimore Sun, April 28, 2009.

5 Doug Brown, “Phoebus First Rate Oriole Hill Frosh—May Be Starter,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1967.

6 Bill Vanderschmidt, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 14, 1964, September 22, 1964, 2D.

7 Doug Brown, “Red Wing-to-Oriole Trip Short Haul for Phoebus as Bird Flies,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966.

8 Bill Vanderschmidt, “No-Hitter For Phoebus,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 16, 1966, 1A, 1D, 2D.

9 Mike Gesker, The Orioles Encyclopedia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 406.

10 Lou Hatter, “Phoebus Hurls 4-Hit Shutout In Debut To Halt Bird Loss,” September 19, 1966, C1; “Music Calmed Tom Phoebus,” Baltimore Sun, September 19, 1966, C6.

11 Lou Hatter, “F. Robinson Hits No. 47 For Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1966, C1, C3.

12 Lou Hatter, “Rookie Sees Scoreless String Go,” Baltimore Sun, September 26, 1966, C1, C2.

13 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide, 1970

14 Lou Hatter, “Salary Hike For Phoebus,” Baltimore Sun, April 29, 1968, C5.

15 Neil Jackman, “Pat Dobson Acquired to Fill No. 4 Sport on Oriole Staff,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1970, 38

16 Press Release, San Diego Padres Baseball Club, Irv Grossman, April 17, 1971.

Full Name

Thomas Harold Phoebus

Born

April 7, 1942 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

September 5, 2019 at Palm City, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.