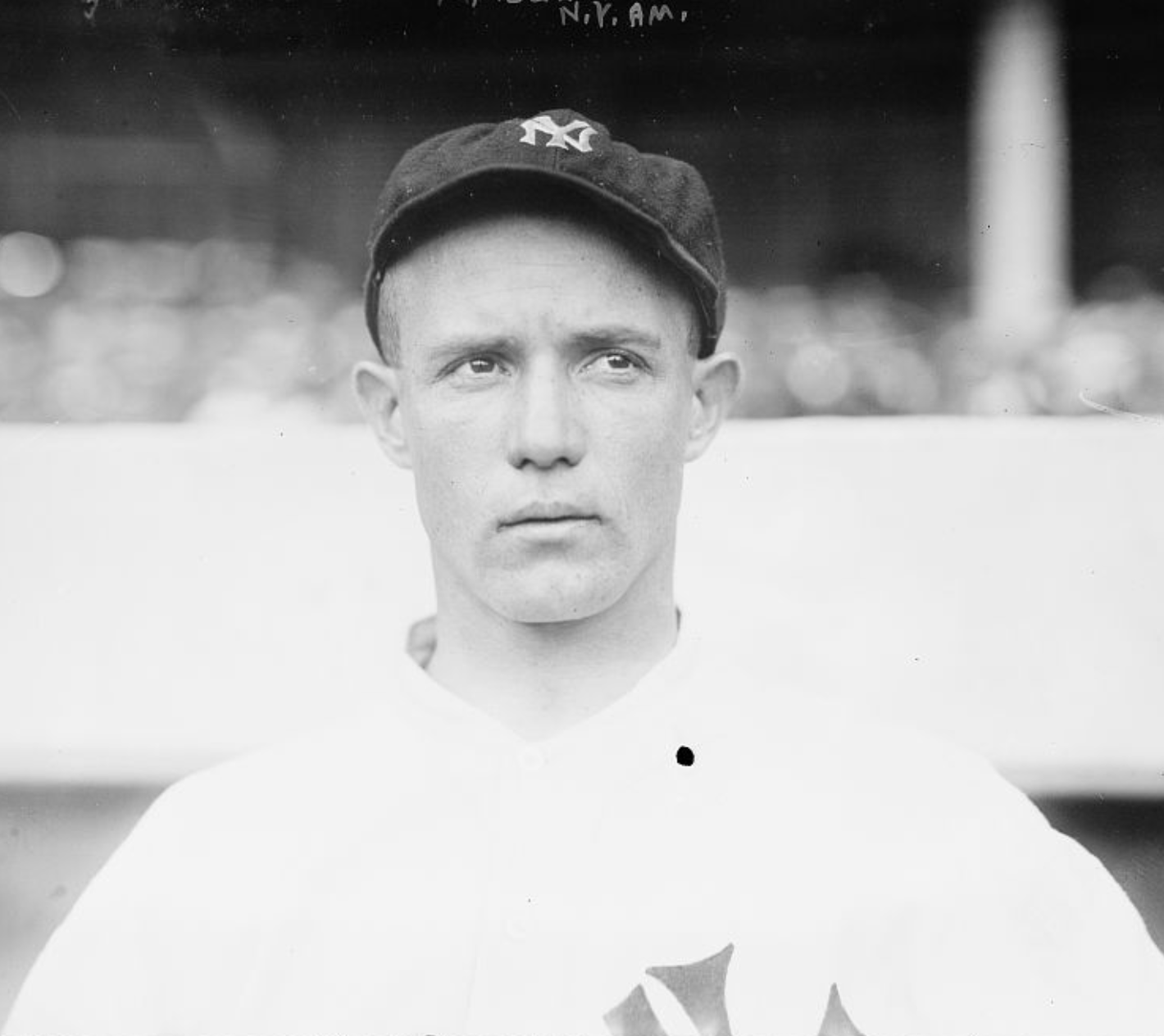

Fritz Maisel

Until Rickey Henderson donned New York Yankee pinstripes in 1985, Fritz Maisel’s 74 stolen bases had been the franchise’s single-season record for 71 years. The diminutive Maisel, nicknamed “The Catonsville Flash” for his Maryland hometown, spent all or parts of six seasons (1913-1918) with the Yankees and St. Louis Browns. For 57 years he was associated with the minor- or major-league Baltimore Orioles as a player, manager, coach, stockholder, director, public relations man, or scout. When Baltimore won seven straight International League (IL) pennants from 1919 to 1925, Maisel was their captain and third baseman.

Until Rickey Henderson donned New York Yankee pinstripes in 1985, Fritz Maisel’s 74 stolen bases had been the franchise’s single-season record for 71 years. The diminutive Maisel, nicknamed “The Catonsville Flash” for his Maryland hometown, spent all or parts of six seasons (1913-1918) with the Yankees and St. Louis Browns. For 57 years he was associated with the minor- or major-league Baltimore Orioles as a player, manager, coach, stockholder, director, public relations man, or scout. When Baltimore won seven straight International League (IL) pennants from 1919 to 1925, Maisel was their captain and third baseman.

Frederick Charles “Fritz” Maisel was born on December 23, 1889, in Catonsville, about 10 miles west of Baltimore. His parents, Christian and Eleanora (Dill) Maisel, had 11 children, nine of whom survived to adulthood. All four of Fritz’s grandparents were from Germany, and his father was a carpenter.1 According to the 1910 census, Maisel families occupied five consecutive homes on Ingleside Avenue in Catonsville.

Maisel attended school through the seventh grade. He was the fourth of six brothers. Christopher, the oldest, didn’t care for baseball, but Henry played for a local team, and Ernest pitched.2 George, like Fritz, reached the majors; Simon, the youngest, played sandlot ball. Annie, Laura and Sophie were their sisters. Fritz’s cousin Charlie caught one Federal League game for the Baltimore Terrapins in 1915.

According to the Baltimore Sun, Fritz was just 12 when he debuted with the amateur Manhattan Athletic Club squad.3 In 1904 the paper showed an “F. Maisel” catching for the Young Catonsville Combination4 and appearing for the Ingleside Jrs.5 Maisel also saw action with the Elwood A.C. club as a catcher in 19056 and at shortstop the following year.7 Shortstop became his primary position, but in summer 1906, he pitched for the Suburban Combinations8 and hurled a complete game for the Manhattans while batting cleanup. (George hit second.)9

By October 1907 Fritz was identified as the Manhattans’ assistant captain.10 The following year he played third base for the Maryland Athletic Club team that won the Interclub League championship game at Oriole Park, with 4,600 in attendance.11

Maisel returned to the Interclub League in 1909 with the Suburban Club. In the season finale on September 6, he stole five bases and tripled.12 His manager, Mose B. Strouse, contacted Detroit Tigers skipper Hughie Jennings and arranged a tryout that summer at American League Park in Washington, DC. Maisel wasn’t signed. “I liked his playing exceedingly well, but I was not in need of an infielder then,” Jennings explained later.13

But Maisel’s play for the Suburban Club impressed Jack Dunn, manager of the Class A Eastern League’s Baltimore Orioles.14 That fall, the Baltimore Sun reported that Dunn, Maisel, future Hall of Famer Wilbert Robinson, and racehorse owner John Bartlett went rabbit hunting together.15

“Fritz hits the ball hard, and, as that is supposed to be his most valuable asset, he may surprise some of his friends by landing,” the Sun opined on March 24, 1910.16 Maisel’s defense was shaky though. He made no excuses after committing two exhibition-game errors while playing with a “piece cut off the end of one of his fingers.” That prompted the paper to predict, “That game little Baltimorean will be a wonder with about a year’s experience.”17

The 1910 census recorded Maisel’s occupation as a machinist, but he was about to commence a professional baseball career. After he affirmed that he would play anywhere, Dunn took him to the train station and purchased his fare for the 740-mile journey to join the Elgin (Illinois) Kittens of the Class D Northern Association.18 “I had a one-way ticket away and a $5 bill,” Maisel recalled. “It was make good or starve, I guess.”19

Maisel learned a lot playing shortstop under Kittens manager Mal Kittridge, a former 16-year major leaguer.20 When the circuit disbanded in July, the Kittens were in first place and Maisel was hitting .283 in 55 games.21 He spent the remainder of the season with the last-place Wheeling (West Virginia) Stogies of the Class B Central League. Although Maisel batted just .238 in 62 contests, Wheeling skipper Bill Phillips wanted him back the following year. But the Sun reported that Kittridge, hired to manage the Class C Saginaw Krazy Kats in 1911, also desired Maisel. “Mal says Maisel is a wonder in the field and lightning-like on bases.”22

Dunn, however, decided to keep Maisel with the Orioles, initially as a utility infielder. That spring, Maisel experimented with switch-hitting as Dunn sought to correct his tendency to step in the bucket and miss curveballs against right-handed pitchers.23 Maisel soon claimed the starting shortstop job, and despite losing time to an infected left foot and leg from a spike wound, he appeared in 103 games and hit .233.24

The Eastern League became the Class AA IL in 1912. In 129 games Maisel batted .276 for Baltimore and paced the circuit with 58 stolen bases, one more than Rochester’s Tommy McMillan.25 In September the Orioles welcomed George Maisel, who had been leading the Class B Tri-State League in steals during his first professional season. “Go to Catonsville for speed,” Dunn quipped.26

Despite Fritz’s improvement, Orioles rooters were tough on him. They greeted the club’s decision to bat him leadoff in 1913 with skepticism. “But Maisel showed almost from the start that his judgement on balls and strikes was considerably better after the winter layoff,” wrote the Sun. “These days he waits ’em out in fine style, hits the ball hard and is so fast that he gives every fielder a hard job throwing him out at first.”27

Maisel led the league with 44 steals and 119 runs scored in just 111 games.28 He also discovered that he was more comfortable at third base after shifting there. Boston Braves scout Bud Sharpe believed that Maisel was major-league ready. The Braves and the New York Yankees each were willing to pay $10,000 to acquire him, according to the August 5 edition of the Sun. But Dunn also wanted players in exchange, and Boston didn’t have any that he was interested in.29 On August 8 Maisel was traded to the Yankees for outfielder Bert Daniels, third baseman Ezra Midkiff, and $12,000.

“The new Yankee is so small that the bleacherites can’t see him until he gets down as far as second base, but he shows a lot of energy in the field,” reported the New York Times. The 5-foot-7, 170-pound Maisel went 0-for-3 with a walk, a stolen base, and a run scored in his debut on August 11, 1913, against the St. Louis Browns at the Polo Grounds. Although he erred on one of his four defensive chances, he also “made a brilliant play, the best of the game” on a bunt by Jimmy Austin.30 The Yankees, who entered the contest with the majors’ worst record, won, 6–2.

Maisel notched his first hit on August 14 in Chicago, a single off southpaw Reb Russell. When the White Sox visited on September 18, Maisel went 4-for-4 against Russell and righty Big Ed Walsh. In between he faced Washington Senators ace Walter Johnson for the first time. “‘Don’t look for anything but speed … Start swinging when the ball leaves his hand,’” Maisel recalled his teammates telling him. He struck out on three pitches despite choking up even more after seeing the first one. “For all that speed, his arm was long and skinny and it didn’t look like he had a muscle in it. But what a motion he had. He never tired … He’s the best I ever saw.”31

The Sun reprinted Frank Roth’s observations about Maisel from New York’s Globe. “He has the style of Kid Elberfeld … It was whispered that Fritz could run bases and field his position great, but that he was shy on the hitting and that he was the worst ‘sucker’ in the world for a curved ball. In spite of the fact that everything said seemed true, we would like to mention that Maisel will do if he hits around the .250 mark.”32 Indeed Maisel started New York’s final 51 games and batted .257 with a .371 on-base percentage, 33 runs scored, and 25 steals.

When Maisel returned home, weather forced the cancellation of a parade in his honor, but the Catonsville Volunteer Hose Company organized an oyster feast with a concert and speeches.33 On November 19 he married Christine Hoerl in Buffalo, New York.34 She worked for a Baltimore candy company, and they had known each other since childhood.35 Their union lasted the rest of Maisel’s life and produced three children: Frederick, Helen, and Bob.

Maisel spurned offers from the upstart Federal League and re-signed with the Yankees in January 1914.36 On February 14 he accompanied Dunn to Mount Saint Joseph High School in Baltimore. The school’s athletic director, Brother Gilbert, had promised the Orioles a player, but southpaw Ford Meadows wasn’t interested in signing. So, Brother Gilbert took Dunn and Maisel to St. Mary’s Industrial School to meet another lefty.37

When Dunn spotted George Herman Ruth, he nudged Maisel and said, “Fritz, there is Rube Waddell in the rough.”38 Long after Maisel retired, he called Ruth the top player of his era, saying, “There was nothing he couldn’t do. He started as a great pitcher, led the world in home runs when not many others were hitting them, was an excellent outfielder with a strong, accurate arm, and even had good speed — could steal a base if you needed it.”39

On April 10 the Yankees visited Baltimore for an exhibition and beat Ruth, who went the distance for the Orioles, 4–0, with Maisel stroking three hits.40 Before 1914 was over Ruth ascended to the majors with the Boston Red Sox. The first homer that he allowed was to Maisel at Fenway Park on October 2. Although it was an inside-the-park round-tripper according to Baseball-Reference, the following day’s New York Times reported that Maisel “slammed the ball into the empty centre field bleachers for a home run.”41

Prior to the 1914 season veteran umpire Tommy Connolly praised Maisel. “I never saw a youngster that showed so much knowledge about stealing bases… What attracted me was the way he hit the dirt.”42 Maisel was one of the majors’ pioneering practitioners of the pop-up slide, and he pushed off his knees with both hands to accelerate quickly.43

On April 22, 1914, the Yankees hosted the Senators while the New York Giants had an off day. “The majority of the Giants chose the contest at the Polo Grounds in preference to the picture shows,” reported the New York Tribune. “Matty (Christy Mathewson), Fred] Merkle, [Art] Fletcher and Hooks] Wiltse, who sat in a group, remarked that Maisel was the magnet which brought them to the grounds.”44

Maisel went hitless that day, but he entertained spectators throughout a record-breaking campaign. On May 20 Yankees fans roared with approval when he stole home in the sixth inning of a 3–1 victory over the Browns by bowling over St. Louis catcher Sam Agnew.45 It was one of four times that he swiped home that year.46 On August 25 Maisel equaled Birdie Cree’s 1911 single-season franchise standard of 48 stolen bases. The next day he established a new mark, and from September 1 through the end of the season, he tallied 23 steals in 31 games to finish with an American League-leading 74. Detroit Tigers’ star Ty Cobb told him, “You little Dutch so-and-so, you beat me this year, but you won’t do it next year.”47 (In 1915, Cobb pilfered 96 bases to set a single-season major-league record for the modern era that stood for 47 years.)

New York rewarded Maisel with a $500 raise. “I was paid $7,500 by the Yankees,” he said. “That was a lot of money in those days, with no taxes.”48 He paced his teammates with 78 runs scored and finished fifth in the AL with 76 walks. His 23 doubles ranked eighth. In 150 games, however, Maisel batted just .239 with two homers. During 1915 spring training, rumors persisted that the Yankees wanted to acquire Frank “Home Run” Baker, who wouldn’t agree to contract terms with the Philadelphia Athletics, to join new manager Bill Donovan’s squad. After Maisel used his thick, powerful wrists to go a combined 6-for-7 in consecutive exhibitions, he sarcastically remarked, “So the Yanks need a third baseman who can hit, do they?”49

As it happened Baker sat out the 1915 season. Although Maisel’s stolen-base total declined to 51, four of them came in one game at Shibe Park on April 17, including another steal of home.50 On June 15 he recorded a career high five RBIs in a four-hit performance against the Browns. Grantland Rice wrote in July, “There is Doug] Baird, of the Pirates, and Hans] Lobert, of the Giants. There is Ossie] Vitt, of the Tigers, and Heinie] Groh, of the Reds. There is Larry] Gardner, of the Red Sox. But for all around value Fritz Maisel is now the leading third baseman of the game.” In the same article Tigers manager Jennings said, “If Maisel was on my club where he could work in with Sam] Crawford and Cobb, he would bat .330, and score almost half again as many runs.”51 Maisel carried a .302 batting average into September before slumping to finish at .281, with four homers in 135 games for the fifth-place Yankees.

Prior to the 1916 season Maisel purchased stock in the Orioles and was named a director of the IL team.52 He retained his shares until Baltimore landed a major-league franchise in fall 1953.53 Meanwhile the Yankees purchased Baker from the Athletics, which meant Maisel would convert to center field, a change he insisted he might have requested anyway. “Tommy] Leach advised me some time ago to switch to the outfield, as he had done,” Maisel explained. “He told me that outfield work would give me several more years of major league baseball than if I stuck to third base, where the legs are subjected to bruises from batted balls, cuts from spikes and strains from quick starts and turns.”54

Following a 1-for-24 start at the plate, Maisel raised his average to .245 before May 14, when he visited Baltimore on an off day. On the train back to New York, he ran into Cleveland Indians first baseman Chick Gandil, who asked him how the outfield was going. “I don’t like it,” Maisel replied. “Some day I’m going to hurt myself going after one of those drives, or else Bill [Donovan] will take me out because I’m no good.”55 When the Yankees hosted Cleveland the following day, Maisel fell and broke his collarbone in pursuit of Jack Graney’s inside-the-park homer.56

Before his next appearance more than 10 weeks later, Maisel still felt sharp pain in his throwing shoulder.57 He made only 15 starts the rest of the year — one in the outfield — and hit just .190 in 58 at-bats. Overall he batted .228 in 58 contests. Worse, on a rabbit-hunting trip that fall, he accidentally shot his brother Ernest in the face, causing serious injuries.58

That offseason Yankees co-owner Captain Huston described the laughable offers that his team received for Maisel. The Browns offered 41-year-old pitcher Eddie Plank, for example, while the Indians proposed Terry Turner, an infielder about to turn 36.59 In contrast prior to Maisel’s poor season, the Yankees reportedly had declined to swap him to the White Sox even up for Shoeless Joe Jackson.60

In 1917 the Yankees moved Maisel to second base. He called for a pitchout with Cobb on first for the Tigers one afternoon and told shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh that he would handle the throw to second base. Maisel was waiting with the baseball when Cobb stopped three feet shy of the bag. “He looked at me and said: ‘Young fellow, you got me that time.’ Cobb raised the first finger of his right hand as he addressed me,” Maisel described. “That really gave me a thrill … But imagine my feelings when I knelt there and permitted him to quickly shove his other hand on the bag as he kept that finger pointed. He had stolen another base!”61

Maisel was in the lineup for New York’s first 72 games, but he hit poorly. After July 8 he started fewer than half of the remaining contests. In 113 games overall, he was one of the AL’s 10 toughest hitters to strike out, and his 29 steals ranked ninth, but he batted just .198. On January 22, 1918, Maisel was one of five players sent to the Browns along with $15,000 for second baseman Del Pratt and Plank, who never pitched in the majors again. St. Louis also received righty Urban Shocker, second baseman Joe Gedeon, catcher Les Nunamaker, and southpaw Nick Cullop.

“I would rather be a St. Louis regular than a New York substitute,” Maisel said.62 Despite starting 10 of Browns’ first 15 games and hitting well, he spent most of the early part of the season on the bench behind incumbent third baseman Jimmy Austin. On June 13 Austin became the club’s acting manager after Fielder Jones resigned. When Jimmy Burke became the full-time skipper two weeks later, he moved Austin to shortstop and installed Maisel at the hot corner. Maisel hit .232 with 11 steals in 90 games before World War I caused the season to end prematurely. He missed the club’s final series to start a job with the Baltimore Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company.63 The war ended in November.

On March 29, 1919, the Browns announced that Maisel had been sold to the Orioles.64 The purchase was completed with his blessing after Dunn convinced him that it was a good idea. Maisel was paid about the same salary that he would have received in the majors, and he explained, “I figured I could save a lot more money living at home.”65 Baltimore went 100-49 to win the IL pennant. In 145 games, Maisel batted .336 and topped the circuit in runs scored (135) and doubles (44). His 63 stolen bases trailed only Ed Miller’s 87.

Maisel followed that up by scoring 145 runs and batting .319 in 1920. He also shot an eagle that had nearly a seven-foot wingspan on his father’s property and donated it to the zoo at Druid Hill Park.66 The Orioles won their last 25 contests, finishing 109-44, 1 1/2 games ahead of the Toronto Maple Leafs for a second straight IL title.67 That fall the Sun said, “Fritz is one of the most popular players that ever wore a Baltimore uniform and numbers his friends by the thousands.”68 The Orioles knocked off the American Association’s champions, the St. Paul Saints, to take the Junior World Series.69 The Orioles “three-peated” in 1921, winning an IL record 119 games, including 27 in a row. Maisel stroked 221 hits and batted .339.

Baltimore center fielder Merwin Jacobson described a “left-side hit and run” that the team employed when he batted with Maisel on second base. “I’d bunt, toward third. Maisel, off with the pitch, would round third, never slowing. While the third baseman was running in after the ball and trying to throw me out, Maisel would score, most often standing.”70

From 1919 to 1925 the “Endless-Chain” Orioles won seven straight IL titles and three Junior World Series. Maisel was the team’s captain throughout the run and, outside of 1923, when he battled bronchitis and hit .275 in 99 games, he never played fewer than 135 games or batted below .306. Shortstop Joe Boley was the only other constant for all seven seasons. “[Maisel] used to run so darn fast he’d have some trouble with pulled muscles in his thighs,” recalled Orioles trainer Eddie Weidner. “We didn’t have elastic bandages in those days, so I’d cut up old supporters, take the elastic out of the top, sew them together and make my own bandages. If the pull was bad enough, I’d sew some wooden tongue depressors into the elastic to hold the muscles in place.”71

In his first 14 professional seasons, Maisel totaled 42 home runs, but he went deep 20 times in 1924, followed by 19 in 1925. “Sometimes when we were behind Dunn would yell from the bench, ‘$100 if you hit a home run,’” he recalled. “Twice in one season I hit the nex pittch (sic) for a homer and collected. I told Dunnie I might lead the league in homers if he kept yelling.”72

Maisel hit .315 in 158 games in 1926, but the Orioles finished second behind Toronto despite a 101-65 record. Baltimore slipped to sixth place in 1927, with Maisel batting .294 in his final season as a regular. Although he batted .304 in 1928, he made just 51 appearances for the fifth-place Birds. After Dunn died from a heart attack that fall, Maisel was hired to manage the Orioles. From 1929 to 1932 his teams compiled a .560 winning percentage. Baltimore finished second or third each season, though, and Maisel was replaced by Beauty McGowan for 1933.

From 1938 to 1951 Maisel served as the chief of the Baltimore County Fire Department.73 When Major League Baseball returned to Baltimore for the 1954 season, he became an Orioles scout. For pitchers he said, “First thing I check is whether he throws the high, hard one.”74 Speed, a strong arm, and hustle were the primary traits he sought in position players. “A player who hustles can have a job in baseball as along as he wants one and the public will never forget him. If you hustle, you put pressure on the opposition.”75 Billy O’Dell, Barry Shetrone, and Jim Archer were future big leaguers that Maisel helped Baltimore to sign.76 When Maisel signed his 51st consecutive one-year deal with the Orioles prior to the 1960 campaign, he said, “This is the kind of contract I like.”77

Major League Baseball staged two All-Star Games in 1962, and Maisel attended the first one, in Washington, DC. The MVP was Maury Wills — midway through his record-breaking season of 104 stolen bases. “What Wills has done is wonderful for the game,” Maisel remarked, praising the Dodgers’ speedster as “the best since Cobb.”78

Earlier that year Maisel was honored before an Orioles game for his contributions to Baltimore baseball.79 That summer hundreds gathered at Patapsco State Park to pay tribute to him as the Citizen of the Year.80 He was inducted into the Maryland Hall of Fame in 1963, as well as the Shrine of Immortals, which was for distinguished baseball professionals who had strong Maryland connections.81

Maisel was thrilled when the Orioles won the 1966 World Series.82 He acknowledged that the quality of baseball had improved since he played. “These fellows have to be better than we were on the average. They’re bigger and stronger … We used something that looked like a motorman’s glove in the early days. With these gloves, they make better defensive plays, no question about it.”83

Before being wounded twice during World War II, Maisel’s oldest son, Frederick, had been a professional prospect. Frederick earned a Silver Star for his service in the Normandy Invasion. Later, he taught science at the McDonogh School near Baltimore and coached the institution’s baseball, football, and basketball teams.84

Maisel’s younger son, Bob, became the sports editor at the Sun. Often, he shared stories about a “little round man” – his father. Most of them involved baseball, like the time they went “to see a great catcher” when Josh Gibson’s club visited the Baltimore Elite Giants.85 But Bob also described helping his dad deliver Christmas baskets to the less fortunate each year. “It’s all right to talk about what you’re going to do when you’re (sic) ship comes in,” his father taught him. “But how can you expect your ship to come in, if you don’t send any out?”86

Fritz Maisel was 77 when he died at Saint Agnes Hospital in Baltimore on April 22, 1967. He is buried in Lorraine Park Cemetery. His son Bob reflected, “He had opportunities to return to the majors, both as a player and a coach but turned them down, because family, friends, Catonsville and Baltimore simply meant more to him. He didn’t want any medals for it. That’s just the way he was.”87

At the time of his death, Maisel had been the Yankees’ single-season stolen-base record holder for more than a half-century. As of 2022, Rickey Henderson — with 93 steals in 1988, 87 in 1986, and 80 in 1985 — still is the only Yankee to steal more bases than Maisel in one campaign.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Will Christensen and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org, and https://sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 The 1910 census lists all of Fritz’s grandparents as American born. However, both of Eleanora’s parents were born in the German state of Bavaria according to the 1880 census. The 1870 census records Christian’s father being born in Bavaria, and his mother in Wunderburg.

2 C. Edward Sparrow, “Dunn is Reaping Harvest Off the City’s Back Lots,” Baltimore Sun, January 7, 1912: S1.

3 Sparrow, “Dunn is Reaping Harvest Off the City’s Back Lots.”

4 “Amateur Ball Clubs,” Baltimore Sun, June 20, 1904: 9.

5 “Amateur Ball Clubs,” Baltimore Sun, July 26, 1904: 9.

6 “Games Around Town,” Baltimore Sun, July 18, 1905: 8.

7 “Amateur Ball Clubs,” Baltimore Sun, May 26, 1906: 8.

8 “Amateur Ball Clubs,” Baltimore Sun, August 15, 1906: 8.

9 “Manhattan 7, Dickeyville 7,” Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1906: 8.

10 “Manhattans Annual Reception,” Baltimore Sun, October 28, 1907: 10.

11 “M.A.C. Downs Walbrook,” Baltimore Sun, September 20, 1908: 10.

12 “The Interclub League,” Baltimore Sun, September 7, 1909: 10.

13 Sparrow, “Dunn is Reaping Harvest Off the City’s Back Lots.”

14 Lou Hatter, “Birds Toast Fritz Maisel,” Baltimore Sun, December 23, 1960: 13.

15 “Bold Hunters Hit the Trail,” Baltimore Sun, November 3, 1909: 12.

16 “Egan is an Oriole,” Baltimore Sun, March 24, 1910: 12.

17 “Birds Getting Better,” Baltimore Sun, March 27, 1910:10.

18 Sparrow, “Dunn is Reaping Harvest Off the City’s Back Lots.”

19 “Fritz Maisel Wins Honor,” Baltimore Sun, August 24, 1962: 7.

20 “Maisel is in Demand,” Baltimore Sun, December 7, 1910: 12.

21 “Baseball Briefs,” Buffalo (New York) Evening News, July 16, 1910: 6.

22 “Maisel is in Demand.”

23 “Birds on Even Footing,” Baltimore Sun, April 26, 1911: 12.

24 “Maisel Out of Game,” Baltimore Sun, June 30, 1911: 12.

25 “Toronto Team Was Entitled to the International League Flag,” Buffalo Times, November 27, 1912: 10.

26 “It’s the Maisels Now,” Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1912: 9.

27 “Are Hot After Maisel,” Baltimore Sun, August 5, 1913: 5.

28 Maisel scored 110 runs according to Baseball-Reference, but 119 is the correct figure according to Sporting Life, The Sporting News, the Reach Guide and the Spalding Guide.

29 “Are Hot After Maisel.”

30 “Yankees Win, 6-2; Maisel at Third,” New York Times, August 12, 1913: 8.

31 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 1968: C1.

32 “Some Baseball Gossip,” Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1913: 10.

33 “Maisel is Banqueted,” Baltimore Sun, October 25, 1913: 10.

34 “Fritz Maisel’s Life Contract,” New York Times, November 20, 1913: 9.

35 “Mrs. Christine Maisel Rites Set,” Baltimore Sun, December 20, 1978: A12.

36 “Dunn Now Has Only Four More Orioles to Sign,” Baltimore Sun, January 11, 1914: S1.

37 Marshall Smelzer, “Babe Ruth: From Shirtmaker to $600-a-Year Ball Player,” Baltimore Sun, June 22, 1975: SM14. Meadows made 13 appearances for the Richmond Climbers of the International League in 1915 and posted a 0-2 record.

38 Smelzer, “Babe Ruth: From Shirtmaker to $600-a-Year Ball Player.”

39 Bob Maisel, “Babe Would Have Loved It,” Baltimore Sun, February 4, 1984: B1.

40 “Orioles are Blanked,” Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1914: 10.

41 “Red Sox Pound Yankee Pitchers,” New York Times, October 3, 1914: 9.

42 “Watch Fritz Maisel,” York (PA) Dispatch, December 1, 1913: 7.

43 Hatter, “Birds Toast Fritz Maisel.”

44 “Washington Guile Defeats Yankees,” New York Tribune, April 23, 1914: 10.

45 Heywood Broun, “Steal and Homer Win for Yankees,” New York Tribune, May 21, 1914: 10.

46 “Fritz Maisel Appointed Chief of Baltimore County Firemen,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 1938: 22.

47 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, September 1, 1977: E1.

48 Associated Press, “Fritz Maisel Starts 57th Year Associated with Birds,” Baltimore Sun, March 2, 1966: C4.

49 “Maisel Shows ‘Wild Bill’ He Can Wallop the Ball,” New York Tribune, March 13, 1915: 12.

50 “Yankees Show Dash and Beat the Athletics,” New York Tribune, April 18, 1915: II-1.

51 Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” New York Tribune, July 29, 1915: 13.

52 “Fritz Maisel a Magnate,” New York Times, March 5, 1916: 23.

53 Associated Press, “Fritz Maisel Starts 57th Year Associated with Birds.”

54 “Fritz Maisel Happy Because He’ll Chase Flies,” Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1916: 11.

55 Frank O’Neill, “Bill Donovan Conducting a Big Class in Cheering,” New York Tribune, May 17, 1916: 16.

56 “Fritz Maisel Injured,” Baltimore Sun, May 16, 1916: 10.

57 “Former Federals Sue,” Baltimore Sun, July 27, 1916: 8.

58 “Hunter Shoots Brother,” Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1916: 12.

59 “Huston Thinks Fritz Maisel is a Star Player,” Gazette Times (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), December 18, 1916: 8.

60 “Fritz Maisel an Oriole,” Baltimore Sun, March 30, 1919: CA9.

61 Jesse A. Linthicum, “Sunlight on Sports,” Baltimore Sun, April 12, 1939: 16.

62 “Change Pleases Maisel,” Pittsburgh Press, February 25, 1918: 30.

63 “From Ball Player to Shipbuilder,” Baltimore Sun, September 1, 1918: 13.

64 “Fritz Maisel to Baltimore,” Hartford (Connecticut) Courant, March 30, 1919: Z10.

65 Associated Press, “Fritz Maisel Starts 57th Year Associated with Birds.”

66 “Eagle Presented Park Zoo,” Baltimore Sun, June 8, 1920: 11.

67 James H. Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998): 147.

68 “Maisel Will Not Play, Due to Mother’s Death,” Baltimore Sun, October 1, 1920: 11.

69 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore: 148.

70 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore: 142.

71 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, May 26, 1964: 21.

72 Associated Press, “Fritz Maisel Starts 57th Year Associated with Birds.”

73 “Fritz Maisel Appointed Chief of Baltimore County Firemen.”

74 Associated Press, “Fritz Maisel Starts 57th Year Associated with Birds.”

75 Gordon Beard, “Former Speedster Maisel Says, ‘Hustle Still Pays Off,’” Baltimore Sun, August 11, 1957: 3D.

76 Hatter, “Birds Toast Fritz Maisel.”

77 Malcolm Allen, “Maisel Signs 51st One-Year Oriole Contract,” Chicago Defender, November 16, 1959: A22. (Author’s Note: The Malcolm Allen cited here is the father of the author of this biography.)

78 Gordon Beard, “Maisel, Base Running Great, Enjoys Feats of Maury Wills,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 1962: 2D.

79 “Man of the Year,” Baltimore Sun, June 4, 1962: 16.

80 “Fritz Maisel Wins Honor.”

81 “Fritz Maisel, 77, Ex-Oriole, Dies,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1967: 28.

82 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1967: C1.

83 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” April 27, 1967.

84 “Frederick C. Maisel Jr. Dies; Was Retired Teacher and Coach,” Baltimore Sun, June 6, 1986: 10D.

85 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, February 4, 1971: C1.

86 Maisel, “The Morning After,” April 27, 1967.

87 Maisel, “The Morning After,” April 27, 1967.

Full Name

Frederick Charles Maisel

Born

December 23, 1889 at Catonsville, MD (USA)

Died

April 22, 1967 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.