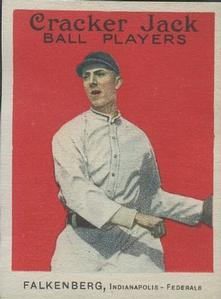

Cy Falkenberg

Cy Falkenberg was perhaps the most unlikely pitching star of the Deadball Era. Nothing special for most of his career, he developed a deadly emery ball at age 32 in 1913, and rocketed to the forefront of major league pitchers. “Falkenberg has upset all possible existing dope, has broken preconceived notions into a million scattered fragments, [and] has set a high-water mark that will stand as long as records stand,” F.C. Lane declared during Falkenberg’s breakout campaign. Just four years later, however, Falkenberg was out of the majors for good after a dalliance with the ill-fated Federal League. A tall, gawky hurler with a peculiar delivery, Falkenberg’s three-year stretch as a dominant pitcher (1912-1914) is often obscured by the fact that one of the three seasons occurred in the Federal League and another in the minors.

Cy Falkenberg was perhaps the most unlikely pitching star of the Deadball Era. Nothing special for most of his career, he developed a deadly emery ball at age 32 in 1913, and rocketed to the forefront of major league pitchers. “Falkenberg has upset all possible existing dope, has broken preconceived notions into a million scattered fragments, [and] has set a high-water mark that will stand as long as records stand,” F.C. Lane declared during Falkenberg’s breakout campaign. Just four years later, however, Falkenberg was out of the majors for good after a dalliance with the ill-fated Federal League. A tall, gawky hurler with a peculiar delivery, Falkenberg’s three-year stretch as a dominant pitcher (1912-1914) is often obscured by the fact that one of the three seasons occurred in the Federal League and another in the minors.

Frederick Peter Falkenberg was born in Chicago on December 17, 1879 (although he would later fudge his baseball age by one year, claiming to have been born in 1880). The blue-eyed boy was the oldest of seven children: “all better looking than myself,” he later insisted. According to census records, Falkenberg’s mother, Agnes, emigrated to the United States from Norway at age 7 in 1868; his father, Frederick A., did the same at age 20 in 1873. They were married in 1879 and settled in Chicago, where the elder Falkenberg worked as traffic manager for a publishing company.

From 1899 to 1902 young Fred Falkenberg attended the nearby University of Illinois, where he joined fellow future big league stars Jake Stahl and Carl Lundgren on the baseball team. Under the guidance of coach George Huff, later manager of the Boston Americans, the Illini posted a 36-13 overall record during Falkenberg’s three years on campus. Falkenberg’s dream was to become an engineer and build public works like the Panama Canal (then under construction in Central America), and he earned his mathematics degree in just three years. But then baseball got in the way.

The Worcester (Massachusetts) Hustlers in the Eastern League tried to sign Fred’s teammate, Lundgren, but when Lundgren signed with the Chicago Cubs, Worcester settled for Falkenberg instead. He pitched a shutout in his first professional game on June 7, 1902, and won 18 games for the season. This performance was impressive enough for Falkenberg to begin the 1903 season with the defending National League champion Pittsburgh Pirates, but he was seldom used, posting a mediocre 3.86 ERA in 56 innings. By August he was back pitching in Worcester. Years later Falkenberg attributed his struggles in Pittsburgh to the fact that he had heretofore skated by on speed alone, but in the majors, his lack of a good breaking pitch was a handicap. He summed up his Pirate experience thusly: “I regretted it, and so far as I know, I’m sure they did also.”

Falkenberg pitched for Toronto in 1904 and Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) in 1905, and during the latter year enjoyed a stroke of good fortune when his old college battery mate, Jake Stahl, was named manager of the Washington Senators. Purchased by the Senators, Falkenberg got his second major league opportunity in 1905. The most notable thing he did was give up the first major league home run of 18-year-old Ty Cobb‘s career, an inside-the-park job at American League Park on September 23.

Falkenberg returned to the Senators in 1906, and in a 6-3 win over Chicago on July 18 became the first post-1900 major league pitcher to hit a grand slam. It was the only home run of his career, and a complete accident. With the bases loaded in the sixth inning, Falkenberg lofted a Texas Leaguer that dropped in front of the outfielders and then, to the amazement of all, took a wacky hop and ended up rolling around under the stands down the right-field line. All four runners, including Falkenberg, scored on a hit that barely made it past the infield.

In almost every news item written about Falkenberg, the first thing mentioned was his height. Falkenberg was tall and lanky; at about 6’5″ and 178 pounds (published reports range between 6’4½” and 6’6″), he was the tallest regular major leaguer of his era. In those pre-Randy Johnson days, however, such a build was actually considered a drawback for a pitcher. “No one could call Falkenberg ‘ideal’ as to formation,” a Sporting News scribe observed in 1911. “He is built on bean-pole lines, stands several inches over six feet, and carries just enough flesh to knit his bones together.” Considered a physical curiosity, “the human obelisk” even posed for a bare-chested anatomical illustration in the October 1913 issue of Baseball Magazine. As recorded by the magazine, Falkenberg’s wingspan measured 79½ inches, or one inch longer than that of the famously long-armed Walter Johnson. “Falkenberg is not the handsomest man in the world,” F.C. Lane wrote. “Neither was Abe Lincoln. But pitchers are not hired on their looks.”

In both 1906 and 1907 Falkenberg gave Washington 200-plus innings of league average starting pitching, posting records of 14-20 and 6-17. But his patron, Stahl, was gone by 1907, and when Falkenberg started off the 1908 season with a 6-2 record, the Senators sold him (along with utility man Dave Altizer) to Cleveland for $5,000. After the season, Falkenberg returned to the nation’s capital to marry Edna Russell, a telephone operator he had met there.

Like many pitchers of his day, Fred Falkenberg probably got his nickname by reminding someone, somewhere, of Cy Young. Although it is tempting to speculate that the name dates from Falkenberg’s days as Young’s teammate in Cleveland (1909-1911), the moniker “Cy Falkenberg” appeared in the Washington Post as early as 1906. Whatever the case, Falkenberg in Cleveland continued his career as a well-established mediocrity, posting records of 10-9, 14-13, and 8-5 from 1909-1911. After the 1911 season he came into conflict with new Naps manager Harry Davis, who was unsympathetic to an illness that had limited Falkenberg’s time on the mound. In December 1911 Davis dispatched Falkenberg to Toledo, an unofficial Cleveland farm team.

Sometime before 1913, Falkenberg learned the trick pitch that would soon rocket him to unexpected major league success: the emery ball. Until then, Falkenberg’s repertoire had consisted of an average fastball, an average curveball, and a seldom-used spitball. The emery ball, meanwhile, had been the secret weapon of Yankee hurler Russ Ford. The pitcher kept a small piece of emery paper hidden in his glove, and when the occasion called for it, he would use the board to scuff one side of the ball, which caused remarkable dips and dives over the 60 feet the ball traveled toward home plate. Although the emery ball was not technically an illegal pitch, Ford, upon reaching the majors in 1910, tried his best to keep it a secret by disguising it as a spitball. However, the emery ball was soon discovered and employed successfully by a handful of other pitchers, including Falkenberg, who was said to have learned it from Toledo infielder Earle Gardner, an ex-teammate of Ford’s. “Russ Ford of the Yankees started it and I improved upon it,” Falkenberg was once quoted as saying of the emery ball. “None of us had any qualms of conscience.” Presumably working on his new emery ball during his lone season as a Toledo Mud Hen, Falkenberg posted a sparkling 25-8 minor league record in 1912 and was re-purchased by Cleveland before the 1913 season. The string bean got healthier during his year in the minors, too, gaining about 20 pounds and also giving up smoking.

Then in 1913, at age 32, Falkenberg enjoyed one of the best breakout seasons in the game’s history, going 23-10 with a 2.22 ERA after not pitching a single major league game the previous season. Like Houston’s Mike Scott nearly 75 years later, the aged Falkenberg’s transformation from mediocrity into marvel was due largely to the addition of a single dynamite pitch to his repertoire. “The main thing that makes Falkenberg’s record so out of the ordinary is that he was considered a has-been, never very brilliant in his prime,” Baseball Magazine wrote. Falkenberg “was always ranked as a fair or indifferent workman at his craft.”

According to Baseball Magazine, Falkenberg’s new emery ball made it seem like he “could make a ball almost stop at will in midair about where he wished to,” then change directions. Like Ford before him, Falkenberg went to considerable lengths to hide the identity of the pitch, calling it “my fall-away” in interviews.

Falkenberg won these raves by starting the 1913 season with complete-game victories in each of his first eight starts and after a no-decision, he won two more to stretch his record to 100. This streak, of course, paled in comparison to the 16-game winning streaks turned in by Walter Johnson and Joe Wood the previous year, but was still impressive enough to establish Falkenberg as one of the league’s top hurlers. Falkenberg’s streak was finally snapped on June 9 by the World Champion Red Sox, who beat him, 4-1. Falkenberg slumped in June, going 1-5, but rebounded to post a 6-1 mark in July and ended the season at 231-0. His record was compiled mostly against the league’s weak sisters–he went 12-1 combined against the three worst teams in the league, and only 4-6 against the two best. But such details went unnoticed as the Naps rode Falkenberg’s right arm to an 11½ game improvement in 1913, staying in pennant contention most of the season after a second-division finish the previous year.

Because of the unusual movement on his emery ball, Falkenberg became known as something of a lefty-killer despite being a right-handed pitcher. In June 1913, Frank Baker declared Falkenberg’s “fadeaway” to be superior to Christy Mathewson‘s. “I would like to see how many hits a team composed entirely of left-handed batters could make against Fred,” Baker said. “I’ll bet he would come mighty close to pitching a no-hit game.” Cy also stood out for his unusual pitching motion. “Players who have batted against Falkenberg have always contended that his delivery is the most peculiar they have ever faced,” the Washington Post‘s Ed Grillo noted in 1908.

During his offseasons, Falkenberg worked 48-hour weeks as a seat upholsterer for the Overland Automobile Company, and was a member of the Machinists’ Union, Local 68. Falkenberg operated a tufting machine, “a contrivance for making back and seat cushions,” he said. “Day by day I thumped and pounded the long curled bale into that machine, getting a great deal more of good, solid exercise for my throwing arm than if I were pitching a game every day.” Although someone with a university mathematics degree might reasonably hope to find a better job than manual labor, Falkenberg appears to have found his work rewarding.

In 1913 Falkenberg gave the first hint that he might be interested in baseball labor issues, becoming a director of the Base Ball Players’ Fraternity, the nascent forerunner of the players’ union. Before the 1913 season he had negotiated a raise to $3,250 per season, after making between $1,800 and $2,800 in every previous year of his career. After his tremendous 1913 success Falkenberg seemed in line for even a bigger raise, but could not reach agreement with Cleveland on a contract. This was good news for proponents of the outlaw Federal League, which, in its bid to become a major league, spent that offseason raiding as many players as it could from American and National League rosters. In January 1914 one of Falkenberg’s old teammates, Larry Schlafly, became manager of the Buffalo Feds and visited Cleveland to try to recruit Cy for the new league. Falkenberg was then given a train ticket home to Chicago, where he was wined and dined by Federal League President James Gilmore. Eventually, Falkenberg agreed to a three-year contract worth about $15,000, almost twice what he had been making in organized baseball. “All told,” he said, “I feel assured of terminating my baseball career, under circumstances far more profitable to myself than I ever hoped for.”

With the Indianapolis Hoosiers, Falkenberg quickly established himself as one of the finest pitchers in the Federal League, going 25-16 with an ERA of 2.22, fourth-best in the league. He also led the fledgling circuit in innings pitched (377⅓), strikeouts (236), and shutouts (9). He also pitched the best game of his career that year, a one-hitter against Buffalo on August 12. Thanks to the stellar performances of Falkenberg and Benny Kauff, the league’s top hitter, the Hoosiers won the inaugural Federal League pennant by a game and a half over Chicago. Their offer to take on the World Series champion Boston Braves was politely declined.

In 1915 Falkenberg got off to a poor start with the Newark Peppers (as the newly renamed and relocated Indianapolis team was called). That August, with Newark in a tight pennant race, they shipped Falkenberg (9-11) off to the woeful Brooklyn Tip-Tops in exchange for a younger pitcher, Tom Seaton. The trade backfired in a big way, as Falkenberg threw 48 innings with a 1.50 ERA for Brooklyn the rest of the year, while Seaton posted a 2-6 record for Newark. The Peppers finished in fifth place.

When the Federal League folded after just two seasons, there was still one year remaining on Falkenberg’s three-year contract. Federal League magnate Harry Sinclair was still legally obligated to pay, but the record is unclear on whether Falkenberg ever got his money. But that was not the worst news for Falkenberg that winter. The emery ball–Falkenberg’s bread-and-butter pitch, and the only reason he was even in the majors–was now banned from the American League. On September 12, 1914, umpire Tommy Connolly had found a piece of emery paper hidden in the glove of Yankees pitcher Ray Keating. Although there was officially no rule against this, Connolly sent the emery paper and a pair of scuffed balls to Ban Johnson for a ruling. Ten days later came the official decree: The emery ball would henceforth be illegal, with violators subject to a $100 fine and 30-day suspension. In effect, it was not just the emery ball that was banned from the American League–Cy Falkenberg was, too. Unable to hook on with a major league team as a result, Falkenberg signed to pitch the 1916 season in the city of his greatest major league success–Indianapolis. Cy posted a 19-14 record for the Indians of the American Association, and led the league with 178 strikeouts.

The next spring, 1917, Falkenberg beat Connie Mack‘s Athletics, 3-1, in a spring exhibition game, renewing hopes that the Cy of 1913 and 1914 had returned. “Mack told newspapermen that Falkenberg never looked better in his life and, even with the Indianapolis team behind him, he could win lots of games in the American League,” one newsman reported. Indeed, shortly thereafter, Falkenberg got one last chance in the majors when Mack traded pitcher Jack Nabors to Indianapolis for him. A report from that season noted that Falkenberg “is one pitcher who improved tremendously with age. Formerly erratic, he acquired steadiness and poise through experience and is now a smooth, consistent toiler on the tee.” However, Falkenberg pitched poorly in 15 games with Philadelphia, and on July 6 the Athletics returned him to Indianapolis for “failure to make good.” The stint with Mack’s men was the last major league action Falkenberg would ever see. He spent two more seasons at the highest levels of the minors–Indianapolis in 1918, Oakland and Seattle in 1919–before calling it a career. During the 1918-19 offseason he also worked in a shipyard in Superior, Wisconsin, in order to help the war effort and, presumably, stay out of the draft.

During his playing career Falkenberg had expressed his desire to someday become a pecan farmer in Florida, but after spending a season in the Pacific Coast League he had other ideas. Falkenberg moved his family to San Francisco, where he turned his concentration to managing a bowling alley. (Even during his magical 1913 season, Cy had been quoted as saying “I like to bowl better than I like to pitch”; he boasted a 200-per-game average.) In 1934 Falkenberg founded the Diamond Medal Tournament, sponsored by the San Francisco Chronicle, which according to his 1961 obituary “has run without a break ever since and has become one of the most popular [bowling competitions] on the West Coast.” Falkenberg continued to follow baseball as a fan, but according to one obituary, “Cy often spoke with scorn about the ‘coddled, pampered modern-day pitcher.’”

Cy Falkenberg died at age 80 in San Francisco on April 15, 1961; he was survived by Edna, his wife of 52 years, and their children, Frederick A. Falkenberg and Doris Bisler. Falkenberg was interred at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California, where in later years he would be joined by fellow ballplayers Joe DiMaggio, Frank Crosetti, George Kelly, Ping Bodie, and Hank Sauer.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Baseball Magazine. August 1913, September 1914, July 1915.

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

Bill James and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Fireside, 2004.

New York Times

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Full Name

Frederick Peter Falkenberg

Born

December 17, 1879 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

April 15, 1961 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.