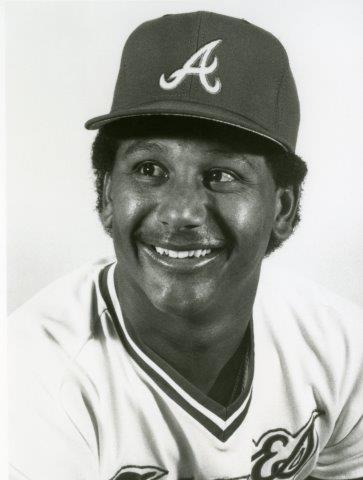

Rafael Ramirez

In March 1993 Rafael Ramirez was trying to secure a bench spot on the rebuilding Oakland Athletics. He was among the first cuts, nursing a sore arm and having been outplayed by another veteran, Dale Sveum.1 The 35-year-old shortstop’s career was effectively over. He spent 13 big-league seasons fielding grounders on two of the most inhospitable surfaces in the major leagues, the rocky terrain of Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium and the concrete-like turf of the Houston Astrodome. Both surfaces were different in their makeup, but they were similar in their mistreatment of infielders. In Atlanta, bad hops ricocheted off small pebbles and rocks, while in Houston, seams turned otherwise fieldable groundouts into errant singles. Yet Ramirez was undaunted in his service at the position, even through the constant scrutiny and criticism he faced. He was error-prone, but that rarely kept him out of the lineup. What kept him penciled in was his ability at the plate and his desire to do better every night.

In March 1993 Rafael Ramirez was trying to secure a bench spot on the rebuilding Oakland Athletics. He was among the first cuts, nursing a sore arm and having been outplayed by another veteran, Dale Sveum.1 The 35-year-old shortstop’s career was effectively over. He spent 13 big-league seasons fielding grounders on two of the most inhospitable surfaces in the major leagues, the rocky terrain of Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium and the concrete-like turf of the Houston Astrodome. Both surfaces were different in their makeup, but they were similar in their mistreatment of infielders. In Atlanta, bad hops ricocheted off small pebbles and rocks, while in Houston, seams turned otherwise fieldable groundouts into errant singles. Yet Ramirez was undaunted in his service at the position, even through the constant scrutiny and criticism he faced. He was error-prone, but that rarely kept him out of the lineup. What kept him penciled in was his ability at the plate and his desire to do better every night.

Rafael Emilio Ramirez Peguero was born in San Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic, in 1958. He came from a well-to-do family and graduated from Liceo Gaston Fernando Deligne high school in 1977.2 What his homeland lacked monetarily it made up for in shortstops and was known as “La Tierra de los Torpederos”3 or land of the shortstops. Ramirez was one of many youths who escaped the poverty-stricken region for the diamonds of the United States during the 1970s and ’80s. However, Ramirez was not a shortstop at first.

After signing with the Braves as an undrafted free agent in 1976, Ramirez played the outfield for several games with Bradenton of the rookie Gulf Coast League. Skipper Pedro Gonzalez, the man responsible for signing the outfielder, made a move that would forever change the youngster’s career. The Braves had languished in last place for most of the 1970s after a 1969 season that saw them appear in the first-ever National League Championship Series. One of the gaping holes in the Braves’ lineup was at shortstop. Several players, including Sonny Jackson and Pepe Frias, had tried to nail down the position. With maverick new owner Ted Turner at the helm, the expectations were high that the team was going to win … and soon. If it was to do so, a new shortstop was in order.

It was apparent early on that the transition would be a difficult one. Even at his normal position, Ramirez made three errors in 11 games before his move to the infield. After being moved to shortstop, he made 29 errors in 30 games. At the plate, he didn’t fare much better, batting a paltry .177. Still, he was only 19 years old. In 1978 Ramirez split time between Class-A Greenwood and Double-A Savannah, where the errors continued. The shortstop spent all of 1979 at Savannah, and though his batting average plummeted to .207, just above the Mendoza line, his fielding continued to improve. As the 1970s closed, a major-league opportunity seemed to be on the horizon for the budding shortstop.

In 1980 the Braves entered spring training with high hopes. Ted Turner had promised to bring a winner to Atlanta. “I don’t want to see any more headlines calling Atlanta ‘Loserville, USA,’” he announced.4 The club featured young sluggers Dale Murphy and Bob Horner, with veteran knuckleballer Phil Niekro anchoring the rotation. To add playoff experience, the team acquired first baseman Chris Chambliss from Toronto along with slick-fielding shortstop Luis Gomez. Though there were other challengers for the position, Gomez proved to be Ramirez’s greatest obstacle. The prospect was the last cut of the spring.5 Skipper Bobby Cox’s choice was difficult, but he knew that Atlanta needed a steady anchor for a position that for a decade had been a problem to fill.

By August the manager’s patience had waned, and the time had come to bring up Ramirez.6 Gomez was fielding well, but his offense was lagging. The heir-apparent was batting .281 with five homers at Richmond. The incumbent, though not pleased to be benched, saw the writing on the wall. Said Gomez, “When I came to the Braves, I was really excited because I saw no shortstop in the organization ready to play. Then I saw Raffy in the spring, and I knew immediately that he was going to be the man for the future. You can’t mistake talent. I realize my role will be as a utilityman in the future.” Losing his job to a “macorisano” was nothing new to Gomez. Several years before, he had lost his starting job in Toronto to another native of San Pedro de Macoris, the newly acquired Alfredo Griffin; Griffin went on to win the Rookie of the Year Award. 7

On August 4, 1980, Ramirez debuted as a pinch-runner late in a game at home versus Los Angeles. The next day he started at shortstop and went hitless in three at-bats, though he and Glenn Hubbard combined for a double play, the first of many to come for one of the most underrated double-play combos of the time. In that game, Ramirez also made his first error, on a grounder off the bat of Ron Cey. On August 6 Ramirez’s fielding woes caused controversy. With one out in the top of the ninth, Dodgers Bill Russell and Dusty Baker hit back-to-back singles. Steve Garvey then hit a grounder to second. Hubbard fielded the ball and relayed it to Ramirez covering the bag. The rookie failed to touch the base before relaying to first. Garvey was called out at first, but second-base umpire Jerry Dale called Baker safe at second. This incensed Bobby Cox, who charged Dale to argue the runner was out. During the argument, tobacco juice made its way from the manager’s mouth to the umpire’s left eye. Dale claimed Cox spit on him; the manager had no comment. Regardless, Baker was still safe and no error was charged to Ramirez; the Braves lost 6-2. Of the misplay, Dale commented, “Ramirez must have thought he was still in the International League where they have two umpires and you don’t have to hit the bag. We have four umpires and you have to hit the bag.”8 On August 9 Ramirez picked up his first hit, an RBI single off Bob Knepper in the second, the first of his four hits in the game. Little did Ramirez and the Braves know that their savior at shortstop had been found, though it would not be an easy ride.

Ramirez batted .267 in 1980 as the Braves improved over the final weeks of the season.9 He made 11 errors in 46 games and helped turn 25 double plays. Things were looking up in Atlanta. However, a strike-shortened 1981 season dashed the hopes for the club. Ramirez struggled both in the field and at the plate. His batting average dipped to .218, and he led the league with 30 errors. After a dismal season, Cox was fired and, under new skipper Joe Torre, Ramirez’s job seemed in jeopardy.10 But Torre brought with him a can-do attitude and a whole new set of coaches. One of them was Dal Maxvill, a former infielder with plenty to teach the young shortstop.11 Ramirez would need his help if he was going to remain in the big leagues.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, following the 1981 quagmire of a season, the Braves seemed ready to return to the drawing board once again at short. The team explored the option of signing veteran Mark Belanger. As well, Joe Torre pointed to backup Jerry Royster as a possible option should Ramirez struggle. “Ramirez is our shortstop, but if Royster were to have a good spring and look like the better player for the job, then naturally he’d win the position,” said Torre.12 Ultimately the club stuck with the incumbent. General manager John Mullen announced, “Shortstop is no longer a priority.” However, an endorsement from Ted Turner helped even more. “We all like him. … Everybody says he’s going to be a great player,” chimed in the owner.13

Maxvill, a 14-year big leaguer, quickly noticed a few things about his new pupil. “He had all the skills. He had a great arm, great hands, good range, very good temperament. The only things he lacked was experience and experience under pressure, and he’s getting that now,” the coach said.14 His tutelage of Ramirez paid big dividends in 1982. Though he led the league with 38 errors, Ramirez led NL shortstops in putouts (300) and in double plays (130). His batting average also returned from the grave, rising 60 points to .278. The youngster’s play in the field began to draw comparisons to that of perennial All-Star Dave Concepción of Cincinnati.15 With comparisons like that, the pressure Maxvill mentioned was coming at Ramirez like a screaming line drive.

The Braves got off to a quick start in 1982. Ted Turner had dubbed the club “America’s Team”16 before the season and predicted the team would finish first in the West.17 Taking their boss’s prediction seriously, the team won a record 13 games in a row to start the season. Ramirez batted .333 with a homer and nine RBIs over the stretch and made only two errors while assisting in 11 double plays. Shockwaves moved throughout the National League regarding the upstart Braves. Commenting on the ever-growing crowds at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Bob Horner quipped, “Usually, when there’s excitement in a game we played, it was the other team doing something special.”18 Torre commented of the team’s reversal of fortune from the previous season’s misery, “They’re the same faces, but not the same players. I think that the time comes when, with experience, some guys begin to reach their potential. I think that’s what is happening here.”19 Still, the skipper kept it all in perspective, remarking, “Baseball is a long season. What I’m trying to do is keep the idea of a streak down with the players and keep the idea of playing good baseball up.”20 The Braves would need to follow that sage advice if they were to survive the season and take the division, for they soon learned that the baseball gods giveth and they taketh away.

After the win streak, the Braves suffered five straight losses and began a roller-coaster ride that saw them in first for most of the season. By July 29 “America’s Team” was standing high atop the division, nine games ahead of second-place San Diego. Ramirez was batting .267 and he and Glenn Hubbard led the league in double plays. “Last year I tried too hard,” said Ramirez. “Now I’m more comfortable. This is a good team. We’ll go easy to the World Series if we keep playing like we’ve been playing.”21 But on July 30, the bottom began to fall out.

From July 30 to August 18 the team went 2-19, including an 11-game losing streak, and fell from first place. Ramirez batted .205 over 19 games of that 21-game drubbing. Now the Braves were four games behind Los Angeles. Suddenly, the media began to change its tune. “Are Torre’s Braves Folding Their Tent?” read a headline in the New York Times.22 Sportswriter Mike Davis was even crueler:“That’s right – alert the paramedics. Fire up the respirator. Get this team some oxygen! The Braves are swallowing harder than a high school freshman on his first date. They’ve had their tickets punched – one way to Gag City. It’s chokin’ time in Georgia.” Davis took a shot at Ramirez. “Their lineup does include some legitimate young talent, like Murphy and Horner and Glenn Hubbard. But it also includes people named Rafael Ramirez and Rufino Linares.”23 It was getting ugly.

However, all was not lost. The Braves reeled off six straight victories after the miserable run and found themselves in a tie for first. They battled the Dodgers the rest of the season, finally clinching the division on the last day, thanks to a Dodgers loss at San Francisco. For his part, Ramirez hit .333 with six homers following the 2-19 slide. Though criticism would accompany the shortstop throughout his career, early on the protestations had little effect on Ramirez for one simple reason: language. Early in 1982 the Dominican quipped, “I see the newspapers last year, but not understand everything.”24 There were few complaints now; the Braves were in the playoffs.

The NLCS opponent for Atlanta was the St. Louis Cardinals. The experts were quick to point out the superiority of St. Louis shortstop Ozzie Smith over Ramirez. The Braves shortstop had only eight errors fewer than the entire Cardinal infield. Smith’s fielding percentage was .984 vs. Ramirez’s .956. Though Smith may have been the superior fielder, Ramirez led at the plate. For the season, he hit outhit Smith .278 to .248 and had eight more home runs (10 vs. 2). For the September playoff run, Ramirez turned up the production by batting .324; Smith managed only a .152 average in 46 at-bats. But the postseason is the start of a new season; everyone begins anew.

In Game One, the Cardinals’ Bob Forsch held the Braves to three hits in a 7-0 win. Ramirez was hitless. The Braves picked up their first runs of the series in Game Two, on Ramirez’s single that turned into a “home run.” With two out and Bruce Benedict on second, the shortstop singled up the middle. The hit easily scored the runner from second. The ball rolled under center fielder Willie McGee’s glove to the wall, allowing Ramirez to motor around the bases on what was ruled a three-base error.25 But the Cardinals came from behind to beat the Braves 4-3. In Game Three, the Cardinals scored four times in the second and never looked back. Ramirez led off the game with a single, but that was his only hit in three at-bats. In the field he made his only error of the series. The Braves lost, 6-2. Atlanta’s magical season had come to an end but had most certainly proved to be something to build upon.

In 1983 the Braves spent 83 days in first place, but where you are on the last day of the season is what counts. At the finish line on October 2 Atlanta was in second place, three games behind the Dodgers. It was a disappointing finish. But Ramirez’s star rose to new heights. He flirted with .300 and finished the season batting .297. Ramirez also finished 16th in the MVP voting (Ozzie Smith finished 21st); the winner was fellow Brave Dale Murphy. Once again, Ramirez led the league in errors with 39, but he led National League shortstops with 116 double plays. The Ramirez/Hubbard tandem had formed a smooth double-play combination that closed up the once porous Atlanta middle infield. Joe Torre mused, “Mentally these two are quite a bit alike. They want to be in the lineup every day. You try to give them a night off once in a while and they’ll invent reasons why they should be playing. You hear people say that this player gives 110 percent. I’m not sure I know what that means, except that nobody on the Braves plays harder than these guys.”26 Hubbard said, “It means a lot to me to lead the league in double plays, because last year they didn’t even rank us in the top 20.” Commenting on his tag-team partner, Hubbard added, “I said all along that, once Rafael got comfortable, he’d do a great job and I think that day’s coming.”27

The 1984 season brought yet another bit of luster to Ramirez’s star. The shortstop was selected as a backup on the National League All-Star team. He was the first Braves shortstop to be selected since Johnny Logan in 1959, the first for the club in Atlanta. He joined teammates Dale Murphy and Claudell Washington on the roster, though he did not get in the game. It was the only selection of his career.

At the plate and in the field, the 1984 season was not as productive for the shortstop. His average dropped 31 points to .266. He made only 30 errors, but still led the league at his position. He led NL shortstops with 251 putouts and 94 double plays. At his highest point he batted .325 midway through the season. In the second half he slumped, batting .220. The Braves finished in second place, 12 games behind the eventual National League champion San Diego Padres. Joe Torre, one of Ramirez’s biggest supporters, was fired as manager. Torre lamented, “Probably the worst thing that happened to me was winning the first year we were here because you got people’s mouths watering for what’s next, and we really never got to that plateau.”28 Eddie Haas became Ramirez’s third big-league skipper.

The year 1985 saw the continued deflation of “America’s Team” and the rise of a new threat to Ramirez’s job security. The Braves won just 66 games and went through two managers, Haas and Bobby Wine. They finished in fifth place, 29 games out of first. Though Ramirez had agreed to a five-year contract in early January,29 spring was not easy. In spring training Paul Zuvella competed with Ramirez for the shortstop job, finishing with a higher batting average and six fewer errors.30 Ramirez won out in the end, but it seemed this foreshadowed things to come. Another shortstop, Andrés Thomas, was waiting in the wings. Thomas debuted as a September call-up on September 3 and saw his first game on defense replacing Ramirez in the ninth inning of a game on September 10. Suddenly it seemed like the odds were building against Ramirez.

Another of Ramirez’s supporters was fired after the 1985 season, general manager John Mullen. His replacement was Bobby Cox. One of the first moves made by the new GM was the hiring of field manager Chuck Tanner. Tanner had led the Pittsburgh Pirates “We Are Family” squad to a World Series title in 1979. The veteran skipper came to an Atlanta team at a crossroads. Tanner liked the lineup, but the pitching rotation seemed suspect.31 The Braves hovered around .500 for most of the season until a rash of losses in July sent the team into a tailspin. By season’s end, the Braves were in last place. Ramirez’s average dropped to .240. He played 57 games at third base as Thomas saw more action at shortstop. Ramirez made 21 errors in 86 games at shortstop while Thomas made 19 in 97 contests. Thomas outhit Ramirez, batting .267. With 1987 on the horizon, Ramirez could only ponder what might happen to his playing time in Atlanta.

Ramirez went to 1987 spring training with hopes of maintaining his starting job. Andrés Thomas was nursing a bad shoulder. Ramirez could hear the rumblings about his future, including trade rumors. But the veteran could not focus on any of that. He had to focus on maintaining his job. “They are talking about using Andrés, doing this and doing that,” said the shortstop. “But I have to forget all that talk. I know I can do the job. But if I think about it, it will hurt me.”32 Ramirez was not ready to play utility or be a backup. “They’re moving me around too much,” he continued. “I don’t play relaxed anymore. I want to play all year at one spot, like before.”33 Never a pessimist, Chuck Tanner commented on Ramirez’s situation, saying, “He’s going to be given every opportunity this spring. We think he just has a world of talent.”34 As the Braves broke camp, however, Ramirez found himself in the dugout watching Thomas play the position he had manned since August of 1980.

Early in the 1987 season, Ramirez found himself platooning with Graig Nettles and Ken Oberkfell at third base. But on April 19 Thomas injured his ankle while sliding into a base.35 The injury forced Tanner to use Ramirez at short. Still, the former starter was not happy. “I don’t want to play like this, because I don’t want anybody to get hurt,” he said.36 Though the veteran was still demanding a trade, his optimist skipper Tanner said, “We’re fortunate to have Ramirez. He’ll do a great job for us.”37 Upon Thomas’s return, both shortstops seemed to flip-flop starting assignments and trips to the disabled list; Thomas had shoulder and ankle issues while Ramirez was nursing knee problems.38 This routine lasted until early August, when the Braves called up yet another shortstop, Jeff Blauser. Thomas was batting .231 with 20 errors and Ramirez .267 with nine errors in 38 games at the time of Blauser’s arrival. With both Ramirez and Thomas battling injuries, it appeared that neither would have a starting job leading into the next season.

In December of 1987, after spending the entire season hoping for a trade, Ramirez was finally granted his wish. The Braves shipped the 28-year-old veteran to the Houston Astros for prospects Ed Whited and Mike Stoker. Atlanta manager Chuck Tanner finally admitted the obvious, stating after the trade, “We decided to go in a different direction in this organization. We’re going with our younger players from our farm system.”39 The Astros, on the other hand, wanted to win right now. Ramirez was very pleased with his new situation. “I wanted to be traded,” he said. “… I just don’t like to sit. I think I’m a better player when I’m in there every day.”40 Ramirez was now healthy and the distraction of the young pups trying to invade his food bowl was now a thing of the past.

His arrival to Houston brought a sense of optimism. The veteran felt his fielding would improve. “I don’t like to make excuses for my play, but fielding on AstroTurf should help,” he said. “The ball will come fast, but there won’t be the bad hops I took in Atlanta.”41 Defensively things improved. Ramirez made 23 errors, six fewer than the league leaders, Cincinnati’s Barry Larkin and his old Atlanta teammate, Andrés Thomas. He batted .276. He had several big hits, including his first career grand slam in late May at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Ramirez claimed the wind was blowing out and that he was only looking to hit a fly ball. Cubs skipper Don Zimmer thought the ball left the yard rather quickly. “I blinked and the ball was gone,” he said.42 The shot was off Mike Capel and helped the Astros to a 7-1 victory.43 The Astros finished in fifth place, just two games over .500, but 27 games ahead of the Braves, who lost 106 games; Chuck Tanner was replaced 39 games into Atlanta’s rebuilding season. Hal Lanier was replaced as Astros skipper by Art Howe after the season.

In his second season in Houston, Ramirez’s average fell once again, but that did not stop him from connecting for some big hits. Strange game-winning RBIs seemed to be his forte for the year. On June 4 came one of the most welcome RBIs of the season and possibly his career. The Dodgers came to Houston for a four-game series. The Saturday game began at 7:35 P.M. The starters were Bob Knepper for Houston and Tim Leary for Los Angeles. After six innings, the score was tied, 4-4. Suddenly, the bats shut off and no one scored for another 16 innings. Strangeness ensued with pitchers playing in the field, fielders pitching, pitchers pinch-hitting, and future Hall of Fame first baseman Eddie Murray playing third. Orel Hershiser and Jim Clancy, usually starters, each appeared in relief and combined for 12 innings of shutout baseball. The Astros used 21 players while the Dodgers played 23. In the bottom of the 22nd, third baseman Jeff Hamilton took the hill to face an exhausted Astros lineup. Bill Doran singled. One out later, Terry Puhl was walked intentionally. Hamilton struck out Ken Caminiti. Rafael Ramirez was next up. On an 0-and-2 count, Ramirez rifled a single over a leaping Fernando Valenzuela at first and into right field, scoring Doran and giving the Astros a 5-4 victory. The game officially ended at 2:50 A.M. Sunday. “I only like to play nine innings. Enough is enough,” Ramirez said.44 Another strange game-winning RBI came in August at the Astrodome. Cubs skipper Don Zimmer ordered an intentional walk with two outs in the ninth to get to Ramirez. One of the knocks against Ramirez had been that he was undisciplined at the plate. With the bases loaded, Cubs pitcher Jeff Pico walked Ramirez on five pitches, giving the Astros a 6-5 win. Ramirez said of Zimmer, “He does some strange things. He knows I’m a free swinger, but I had in mind to be patient and only swing on a 3-and-2 count.”45 Who needs walk-off singles and homers when you can walk with the bases full?

At shortstop, everything returned to normal in 1989. By the All-Star break, Ramirez led the league with 21 errors, almost equaling his total for the previous season.46 Of his struggles, he noted, “When I first started professionally, I could catch and I couldn’t hit. Now I can hit and I can’t catch.”47 Ramirez settled down during the second half of the season, finishing the year with 30 errors, but again leading NL shortstops.

In November Ramirez signed a two-year deal to remain the Astros starter at short. “His signing provides us a continuation of service of one of the best offensive shortstops in the National League,” said Astros GM Bill Wood.48 However, there was an interesting clause in his new contract: a “weight bonus.” Though not a new idea to contracts, this weight clause had an interesting caveat. Ramirez would be weighed daily starting in spring training. If he averaged 187 pounds at the end of each month, the Astros would pay him an additional $12,500. This gave him the chance to make an additional $87,500 for the season on top of his $1.1 million salary.49 Not only would staying trim help Ramirez to be more effective in the field, but it would also give him more in the bank.

Ramirez played 132 games in 1990. But he was now 31 and battling injury and weight problems. The Astros began to field trade offers and were looking at younger options at short, including Orlando Miller, Dave Hajek, Eric Yelding, and Andujar Cedeño. Their first-round pick that year was also a shortstop, Tom Nevers, who referred to Ramirez as “elderly.” “That’s the one thing I was hoping for was to go to a team with an elderly shortstop and not too many people coming up in the farm system,” Nevers said.50 It appeared that Ramirez was on his way out. As to the weight clause, he did not hit the mark at any point during the season, missing it by three pounds for the year.51

In 1991 Ramirez was still in an Astros’ uniform, platooning and coming off the bench. He played behind Eric Yelding and saw action at various positions, including his first career start at second base, on May 28 at LA. He played in just over 100 games, but started only 45 times. To the Astros’ chagrin, neither Yelding nor Ramirez fared well in the field. In fact, on May 25 at home against San Diego, both made errors that cost the Astros a win. Padres infielder Jose Mota singled and reached third when Yelding misplayed the ball in right field. Ramirez, who had replaced Yelding at shortstop in the eighth, then fielded a grounder from Bip Roberts and threw it into the dirt at first, allowing Mota to score what proved to be the game winner. Though the Astros had been optimistic in their seasonal outlook, the team was not contending and began looking to cut payroll. They fielded offers once again for the veteran shortstop. As summer approached, the Dodgers expressed interest as did Oakland, looking for a replacement for the injured Walt Weiss.52 However, Ramirez stayed put.

In 1992 the downhill slide continued. Ramirez signed a minor-league deal to stay with the club.53 The starting shortstop was now Andujar Cedeño as the Astros, reminiscent of the 1970s Braves, continued the shortstop carousel. But by mid-April, with the free-swinging Cedeño coming up empty at the plate, Houston put Ramirez back into the starting role.54 The veteran made sporadic starts throughout the season, save for some time he spent on the disabled list in June. In all, the Astros used six different shortstops in 1992, including Ramirez, Cedeño, Yelding, rookie Juan Guerrero, and veterans Casey Candaele and Ernie Riles. Desperate, the Astros even considered moving number-one draft pick Phil Nevin to shortstop, testing him at the position during a practice session in early September.55 Ramirez started his final game at shortstop on August 22 at Philadelphia. He had one hit in five at-bats and scored twice; he made no errors. On September 29 the Astros were trailing 5-4 and facing Padres closer Randy Myers at home. Ramirez led off the bottom of the ninth with a pinch-single. After a sacrifice by Craig Biggio and a walk to Steve Finley, Luis Gonzalez smacked a walk-off double to left-center to give the Astros a win. It was the final hit of Ramirez’s big-league career. In late October he elected free agency, joining Oakland the following spring, but did not make the team.

Rafael Ramirez collected 1,432 hits for his career and batted .261. He made 290 errors at shortstop. Though perhaps not Hall of Fame worthy, Ramirez certainly made the most of his 13-year career. Now an ex-major leaguer, he returned to San Pedro de Macoris. His son, Edgar Ramirez, was signed as a 16-year-old infielder by the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 1996 and played through 1999, but never made the big leagues. He died at the age of 28 near San Pedro de Macoris.56

As a fielder, Ramirez was error-prone, but he was always ready for the next chance, never wanting to sit the bench. As a hitter, Ramirez was a leader at his position in a time when shortstops were known only for their fielding. He ignored the criticism of the media and performed his duties every game, even when it wasn’t pretty or the playing field that friendly. What manager wouldn’t want a player like Rafael Ramirez?

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted the Rafael Ramirez player file and questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, MLB.com, and Newspapers.com.

Notes

1 McClatchy News Service, “A’s Notebook: Tigers Nibble About Rickey,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 15, 1993: B-4.

2 Steve Wulf, “Standing Tall at Short,” Sports Illustrated, si.com/vault/1987/02/09/114833/standing-tall-at-short-with-more-than-70-shortstops-in-organized-baseball-the-tiny-impoverished-dominican-republic-has-emerged-as-the-worlds-leading-exporter-of-mediocampistas, accessed May 31, 2018.

3 Enrique Rojas, “Buena cosecha de paracortos dominicanos,” Plainview (Texas) Daily Herald, November 24, 2004. myplainview.com/news/article/Buena-cosecha-de-paracortos-dominicanos-8951737.php , accessed May 31, 2018.

4 Joyce Leviton, “Skipper Ted Turner Buys the Braves and Promises to Turn Atlanta into Winnersville, U.S.A.,” People, February 2, 1976. people.com/archive/skipper-ted-turner-buys-the-braves-and-promises-to-turn-atlanta-into-winnersville-u-s-a-vol-5-no-4/, accessed May 29, 2018.

5 “Watch These 13 Rookies,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), April 13, 1980: 6E.

6 United Press International, “Atlanta Moves Up Ramirez,” Hartford Courant, August 5, 1980: 83.

7 Ken Picking, “Braves Bench SS Gomez, Promote Ramirez,” Unattributed August 23, 1980, clipping in Ramirez’s Hall of Fame player file.

8 Mike Littwin, “Dodgers Get a Call – and a 6-2 Victory,” Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1980: 39.

9 Associated Press, “Cox’s Move Looks Good Now,” Herald and Review (Decatur, Illinois), August 20, 1980: 21.

10 See AP, “Braves Finally Sign Torre,” The Day (New London, Connecticut), October 24, 1981: 24, and an unattributed, undated article titled “Braves Give Up on Ramirez Deal,” from Ramirez’s Hall of Fame player file.

11 Lee Whitney, “Have You Noticed Rafael Ramirez?” Braves Banner, October 11, 1983.

12 “Braves Give Up on Ramirez Deal.”

13 “Braves Give Up on Ramirez Deal.”

14 Whitney, “Have You Noticed Rafael Ramirez?”

15 Kent Hannon, “Are Torre’s Braves Folding Their Tent?” New York Times, August 8, 1982.

16 Jason Foster, “The Untold Story of ‘It’s a Long Way to October,’ a groundbreaking, forgotten baseball documentary,” The Sporting News, May 2, 2017. sportingnews.com/mlb/news/its-a-long-way-to-october-atlanta-braves-documentary-video-1982-wtbs-glenn-diamond-joe-torre/yaabhb6wm7h91kirw1ijy0wm9, accessed June 2, 2018.

17 AP, “Atlanta’s Turner Ready to Fly Pennant,” Galveston Daily News, March 12, 1982: 17.

18 Ira Berkow, “Braves Win 12th Straight to Set Record,” New York Times, April 21, 1982.

19 Berkow.

20 Berkow.

21 George Maselli, “Absurd: Who Would’ve Thought the Braves Would Be in 1st?,” Tallahassee Democrat, July 12, 1982: 15.

22 Kent Hannon, “Are Torre’s Braves Folding Their Tent?”

23 Mike Davis, “Braves’ New World Is Coming Apart,” San Bernardino County Sun, August 7, 1982: 33.

24 AP, “Baseball Tidbits: Quotes,” Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa), March 9, 1982: 16.

25 Bob Fowler, “Brewers Force Final Game – Cards Win: Oberkfell’s Single in 9th Turns Back Atlanta, 4-3,” Orlando Sentinel, October 10, 1982: D1.

26 Phil Elderkin, “Hubbard and Ramirez Give Braves Solid Infield Tandem,” Christian Science Monitor, June 21, 1983.

27 Mark Whicker, “Playing Well Is Mounds of Fun for Hubbard,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 1, 1982: 74.

28 AP, “Braves Fire Manager Torre,” Washington Post, October 2, 1984. washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1984/10/02/braves-fire-manager-torre/03373120-47fc-4b18-8598-3ff312b281fc/?utm_term=.86fe389a26a9, accessed May 29, 2018.

29 AP, “A.M. Sportwatch: Braves Sign Ramirez,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), January 17, 1985: 9.

30 “Play Ball: Mahler Gets Call in Braves’ Opener,” Anniston Star (Anniston, Alabama), April 9, 1985: 11.

31 David Moffitt, “Brave Hopes Hurt Again by Pitching,” Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), February 18, 1986: 37.

32 Joe Santoro, “All Ramirez Wants Is a Fair Chance,” News-Press (Fort Myers, Florida), March 20, 1987: 37.

33 Santoro.

34 Santoro.

35 Gerry Fraley, “Rafael Wants Out, But…,” unidentified article in the Ramirez Hall of Fame player file.

36 Fraley.

37 Fraley.

38 “Braves Ship Ramirez to Astros,” unattributed article in the Ramirez Hall of Fame player file.

39 “Braves Ship Ramirez to Astros.”

40 Neil Hohlfield, “…While New Astro Ramirez Soars,” unidentified article in the Ramirez Hall of Fame player file.

41 Frank Carroll, “Astrodome New Home to Ramirez: Ex-Brave Looks to Mend Erring Ways in Houston,” Orlando Sentinel, February 26, 1988: 36.

42 AP, “Ramirez Slam Humbles Cubs,” Herald and Review (Decatur, Illinois), May 29, 1988: 11.

43 “Ramirez Slam Humbles Cubs.”

44 Paul Hagen “In Orderly Fashion: Expos’ Rodgers Goes Alphabetically to Bullpen,” Philadelphia Daily News, June 9, 1989: 121.

45 AP, “’Percentage Baseball’ Costs Cubs, Aids Astros,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, August 19, 1989: 9.

46 AP, “The Inside Pitch: National League: Rose Offers Interesting Insight Into Baseball’s Top Performers,” Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), July 11, 1989: 20.

47 Wire Services, “N.L. Notebook: Houston Astros.” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), July 16, 1989: 36.

48 AP, “Astros Agree to Terms with Rafael Ramirez,” Galveston Daily News, November 16, 1989: 20.

49 Sun News Services, “Kaleidoscope: Calorie Counter Will Be Cash Counter,” San Bernardino County Sun, November 19, 1989: 27.

50 Dave Dye, “Brewers’ Dalton Hasn’t Mastered the Art of the Deal: Draft Story II,” Detroit Free Press, June 10, 1990: 44.

51 Tennessean News Services, “Sports A.M.: Sanderson, Yanks at Standstill,” Tennessean, December 30, 1990: 22.

52 “Dodgers Notes,” San Bernardino County Sun, and Paul Hagen, “Tonight: Phillies vs Houston Astros.” Philadelphia Daily News, June 12, 1991: 84.

53 “Dodgers Notes,” “Tonight: Phillies vs Houston Astros,” and “Briefly: Baseball,” Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), January 9, 1992: 24.

54 Rick Hummel, “Baseball Notebook: Free Agents Are Costing Cubs Plenty,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 19, 1992: 20.

55 Ray Finocchiaro, “NL Notebook: No. 1 Pick Green’s Future May Hinge on Shoulder Surgery,” News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), September 13, 1992: 64.

56 “Scorecard: Obituaries,” unidentified article from Ramirez Hall of Fame player file.

Full Name

Rafael Emilio Ramirez Peguero

Born

February 18, 1958 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.