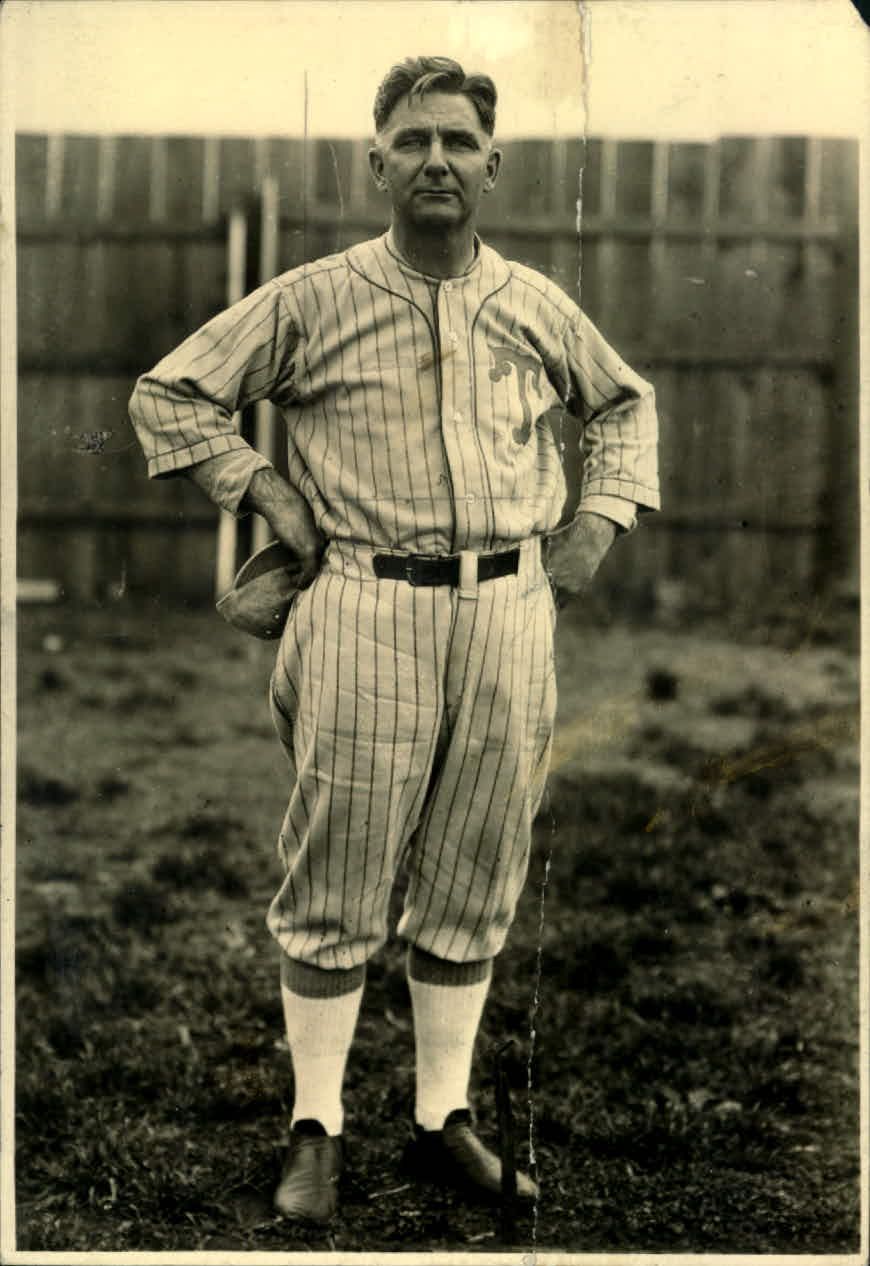

Dale Gear

Dale Dudley Gear, who would become known in baseball from coast to coast as a player, manager, club owner and minor league executive, was born on February 2, 1872, in Lone Elm, Kansas, a small community in Anderson County. He was the third of four children born to Diana Walker and Major W. A. F. Gear., an engineer and Civil War veteran.

Dale Dudley Gear, who would become known in baseball from coast to coast as a player, manager, club owner and minor league executive, was born on February 2, 1872, in Lone Elm, Kansas, a small community in Anderson County. He was the third of four children born to Diana Walker and Major W. A. F. Gear., an engineer and Civil War veteran.

Dale entered Kansas University in 1893 intent on becoming a lawyer. Professor Adams, his economics professor, who also served as KU’s baseball coach, persuaded him to try out for the baseball team, where he came of age as a right-handed hitter and pitcher.1 One day in a pinch, he was called on to pitch against the Winfield (Kansas) Reds, a first-rate semi-professional team that barnstormed throughout Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, introducing America’s game to the middle of the country. Gear dazzled the Winfield nine and won the game. He became a fixture in KU’s lineup for the next three years. The Winfield team was so impressed with Gear’s pitching, they signed him to play for them over two summers. After school was over, Gear and a few of his Jayhawk teammates joined the Reds and earned money by sharing the gate receipts, and sometimes betting on the games. Through their skill and pluck, Gear and his college buddies earned enough money to return for another year of school.2

Gear’s reputation as one of the best pitchers in a four-state area grew as a result of his notoriety with the Winfield Reds. On September 15, 1895, his fame grew even larger as he was brought in as a ringer by Art Maher, a banker from Norman, Oklahoma, to pitch a grudge match Maher had arranged against an Oklahoma City team that featured legendary pitcher Earl “Kid” Bevis. Oklahoma City held the local bragging rights after beating Norman twice during the year. Maher wired Gear $75 plus travel expenses to leave school for the weekend and pitch for Norman. Over 1,000 fans, many of whom made bets on their hometown Oklahoma City team, poured into the ballpark.When Gear showed up 15 minutes before game time wearing a Norman uniform, an Oklahoma City player recognized the ringer and yelled, “It’s Gear! It’s all off.” But the game was played. Kid Bevis featured a drop ball that, on this day, did not drop while Gear poured in curve after curve. Norman won the game, 10-0, and a re-match the following weekend, 12-2. Banker Maher was so happy with the outcome, and the money he pocketed, that he named his next son Dale.3

The next year, a team from Purcell, Oklahoma, claimed to be the “Champions of Indian Territory” after they hired most of the Fort Worth team that had won the Texas League Championship over Dallas. Art Maher again saw an opportunity and arranged a showdown between Purcell and his team in Norman in late September 1895. Again, Maher secured Gear’s pitching talents for the big game. Norman put up six runs in the second inning. Gear gave up a run in the sixth and, in a disastrous eighth inning, Purcell tied the score as Gear’s teammates apparently showed the pressure of the huge amount of money wagered on the game and their own numerous side bets. In the ninth, Gear retired Purcell in order, getting “three of the strongest batters in the Texas League.” In the home half of the ninth, Gear came to bat with two outs and a runner on. He hit a line drive that eluded the center fielder. The run scored, Norman won, and Gear was “picked up on first and carried off the grounds.” His teammates called Gear’s hit a $1,000 strike as they collected on their bets.4

The owner of the Fort Worth team, John L. Ward, attended the game and was so impressed with Gear that he signed him to play for his Panthers the next year at a salary of $125 per month. Gear did not disappoint him with either his pitching or hitting. He won 26 games, lost 5 and tied one while hitting .367.5 In August, Ward sold Gear’s contract to the Cleveland Spiders of the National League and Kansas University student and future lawyer Dale Gear found himself in the major leagues, playing on a team that featured future Hall of Famers Cy Young and Bobby Wallace. He made his debut on August 15, 1896, in a 6-0 loss at Pittsburgh.6

Seeing limited duty at the end of the season, Gear appeared as a pitcher in three games, losing two of them while hitting 6 for 15. His abbreviated season and meager statistics with the Spiders did not stop the Lawrence Journal from bragging about the local kid. “Kansas has produced at least one great ball player this year. His name is Dale Gear and his home is at Garnett….”7 The Cleveland World wrote, “Gear is the find of the season for the Cleveland club…. This young man is destined to become one of the greatest players in the league.”8

At this point, Gear was torn between playing baseball and finishing his legal education. He obviously enjoyed playing baseball and he was making decent money at it, but he saw his future as a lawyer. So, in 1897, Gear opened the season with the Spiders and was used exclusively as an outfielder, appearing in only seven games before he left the team and returned to school. He graduated from Kansas University law school in the spring of 1898 and signed to pitch for the local Kansas City Blues of the Western League. As September rolled around, the Blues found themselves in a tight pennant race with the Indianapolis Reds.

On a Sunday in mid-September, the Reds met the Blues at Kansas City’s Exposition Park before 11,400 fans, the most ever to witness a game in Kansas City. They crowded into the grandstands, bleachers and onto the far reaches of the outfield. Trains brought 150 fans from Topeka and 50 college boys from Kansas University made their presence known by doing their college cheer. They saw Dale Gear pitch nine solid innings as Kansas City took the game, 3-1.9 Two days later, around 8,000 fans, including Dale Gear’s father, were on hand to watch the final game of the season. The winning team would take home the pennant. Again, Dale Gear was called on to pitch the Blues to victory, his third game in six days. Indianapolis took a two-run lead in the second, but Gear scored the first run for Kansas City in the third and the Blues took a two-run lead into the ninth. The Reds scored once and had the tying run on base when Gear got the third and final out to give Kansas City the pennant. The Kansas City Journal recalled the wild scene that ensued:

“A crowd of cheering men surrounded the clubhouse and called for the players. A few moments later Dale Gear was carried from the dressing room on the shoulders of a half dozen enthusiastics and placed on a table in the clubhouse. Then there were demands for “Speech! Speech!” ‘I’m too wild to talk boys,’ protested Gear when he was called upon. ‘No, you’re not, Dale,’ insisted one of the men. ‘You’re not a bit wild. You only gave up two base on balls.’ Back in the corner of the room a group of fans crowded around Dale’s father and congratulated him on his son’s good work. ‘I am exuberantly happy,’ said Mr. Gear. ‘There was one day in the civil war when my regiment took 50,000 men prisoners and we thought that was a great day. But, by God, boys, it was not as grand a day as this.’”10

Gear finished the year with a 25-14 record for the Blues, winning three games in the last week to sew up the pennant and finish 1 1/2 games ahead of Indianapolis. After the final game, the contracts of four of the Blues, including that of Dale Gear, were sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League. Gear never played for the Pirates. He wanted to stay in Kansas City and practice law and over the winter, he took classes at New York Law School. Pittsburgh ended up releasing him so he could return to Kansas City for the 1899 season.

For the next two years, Gear shunned the major leagues and played for the hometown minor league Kansas City Blues of the Western League while in the off-season he built his law practice. His fellow ball players recognized the value to them of his legal education by electing him to serve as Secretary of the Players’ Protective Association,11 an early form of a player’s union. The Association’s main beefs with professional baseball were the reserve clause that forever bound a player to one team and the low salaries paid to players due to collusion by the owners. The Association folded after two years, but this was Gear’s first venture into the business side of baseball.

In 1901, Ban Johnson, President of the Western Baseball League, which had been renamed the American League in 1900, and the league’s team owners, transformed their minor league that included the Kansas City Blues into major league status, setting off a two-year war with the older, established National League. The Kansas City Blues moved to Washington and became the Senators. As a result, Kansas City attorney Dale Gear found himself once again pitching in the major leagues. On May 14 he experienced one of his greatest thrills as a ballplayer, pitching against his former Cleveland teammate, Cy Young, who was now with the Boston Americans. Gear and his Washington team won the game, 3-2, with Gear throwing a complete game for his first major league win. The Washington Evening Star noted:

“It takes considerable nerve to pitch against a man like Cy Young, as with him in the box the prospects of victory for Boston are increased three-fold. The veteran pitched good ball yesterday, but the young Kansas City lawyer did better…”12

Later that summer, on August 10, Gear set a dubious record — one that still stands to this day. In the second game of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia A’s, he established an American League record by giving up 10 extra-base hits and 41 total bases in a 13-0 loss.13 Gear’s record for extra-base hits in a game has been equaled twice, by Luis Tiant in 1969 and Curt Schilling in 2006.14 Gear finished the year, which would be his last in the major leagues, with a 4-11 record and 4.03 era. He batted .236.15

In the fall of 1901, Thomas J. Hickey organized the independent American Association, placing one of eight franchises in Kansas City. Gear, who had returned to his Kansas City law practice, gathered a few partners together and purchased the franchise with Gear serving as team president, field manager and pitcher/outfielder for the Blues the next three years. This set up a baseball civil war in Kansas City between Gear’s Blues and the Western League’s already-established Kansas City Blue Stockings featuring Charles “Kid” Nichols as player-manager.

In 1902 and 1903, Gear and Nichols organized a showdown series between the two teams with the winning team to receive $1,000.00 plus 60% of the gate receipts. Gear’s Blues took the series both years and claimed baseball dominance in Kansas City: “… Dale Gear’s Blues made Kid Nichols’ Blue Sox eat humble pie again this year….The result of the series would seem to indicate that the Western Leaguers are not in the same class with the American Associationists. Gear’s team won the post-season series very easily last year.”16

Despite being the best ball team in Kansas City, the Blues were average or worse in the American Association. In July 1904, with the Blues near the cellar, Gear brought in former big league manager Arthur Irwin to guide the team; by the end of the season, Irwin and a few East Coast investors purchased the franchise. Gear accepted the job as player-manager of the Little Rock Travelers in the Southern League for the 1905 season.

Gear’s year in Little Rock was difficult. Off-field turmoil with the ownership group foreshadowed on-the-field injuries, sickness and lackluster play, which led the Travelers to a last-place finish.17 After the season Gear headed back to Kansas City and announced he was quitting baseball to focus on his law practice, although he left the door open a crack by saying he intended to play outfield for the Birmingham Barons next year.18 This would be the first of several of Gear’s announcements that he was quitting baseball.

Playing strictly as an outfielder and as captain of the team, 34-year-old Gear led the Barons to the championship of the Southern League. Afterward, he returned to Kansas City and formed a law partnership with Armwell L. Cooper, a State Senator, and it appeared that Gear was finally established as a lawyer and out of baseball for good. His retirement only lasted a few months, though, as in May 1907 the United States Government awarded Gear a land grant to a quarter section of land near Frederick, Oklahoma, on the condition that he homestead the land. He had to live on the land and pay $1,000 over five years. So, the former ballplayer and now former lawyer moved to rural Oklahoma to build his house. One month later, Gear was itching to get back into baseball and signed to play center field for Montgomery in the Southern League.19 In mid-season he jumped to the Mobile team in the Cotton States League, after which he again announced his retirement from baseball.

Over the winter, Captain Crawford, owner of the Shreveport Pirates of the Texas League, convinced Gear to manage his team for the 1908 season. Looking for players, particularly a first baseman, Gear contacted a friend in Kansas City who suggested Zack Wheat, who was said to be driving a hog cart in the Kansas City stockyards at the time. The 20-year-old Wheat had little professional experience, having played only six games at Fort Worth in 1907. When Wheat arrived in Shreveport, Gear quickly determined that he was not a first baseman, but he thought he could become an outfielder. As Wheat later recounted:

“I could run and bat some, but I couldn’t catch a ball…Morning after morning he had me out at the Shreveport grounds teaching me how to cover the outfield. Fly balls, ground balls to the right and to the left were my daily portion, and morning after morning I was almost ready to drop when Gear would call off the practice. He persevered and in due time I got so that I did not miss them oftener than anyone else.”20

Wheat’s contract was sold to Mobile in August and the next year he was in the major leagues playing outfield for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Wheat still holds several Dodgers’ franchise hitting records, including most hits at 2,804; in 1959 he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, giving Dale Gear credit for showing him how to be a professional ballplayer.

Gear piloted Shreveport three years, never finishing in the first division of the Texas League. It was said that he ran a clean club that always played good ball, and he made money for his team by selling player’s contracts to major league teams. During the three years, Gear paid out $2,250 for players and sold them for $19,500.21

Between the 1910 and 1911 seasons, Abner Davis, the owner of the Oklahoma City Indians, announced that Dale Gear would manage his team in the Texas League the following year and become a 25% stockholder of the team. Two complications arose. First, Captain Crawford put his Shreveport franchise up for sale and a group of investors from Austin bought it, expecting Gear to continue as the team’s manager. Second, R. E. Moist, previous owner of the Oklahoma City franchise, filed suit regarding the rightful ownership of the franchise. The matter ended up in court and a receiver was appointed to handle the club’s business affairs. Gear had to choose one franchise over the other and he opted for Austin, avoiding Oklahoma City’s legal entanglements.

Seven of the eight teams in the Texas League were evenly matched throughout the year. Only the Galveston nine never spent a day in first place. In late July 1911, Gear’s Austin Senators won a 13-inning game and then another,and ended up stringing together 22 victories — a Texas League record and more than any National or American League team had ever won in a row.22

The Houston Post had difficulty admitting that the Austin team was better than their theirs, giving all the credit to Dale Gear: “Seriously, it is hard to concede how the Senators can beat out Houston for the rag. Houston may not win, but Austin has no license to outclass them, and if the togaed gentlemen do it will be the personality and leadership of Dale Gear that has done it. Gear is a man whose players idolize him and even a mediocre club will win for him.”23 After a close, competitive race for much of the season, Austin breezed to the pennant. It was Gear’s fifth pennant-winning team, but his first as manager.

Within a few weeks, Gear was announced as the new manager of the Topeka Kaws of the Western League. The club president, Chester Woodward, an old college friend of Gear’s, convinced him to take the job.24 Although he retained his farmland in Oklahoma, the 40-year-old Gear would spend the rest of his life in Topeka. Gear found the Western League to be faster than the Texas League as his Kaws were consistent second-division teams. By the summer of his third year as manager, and shortly after the team lost 16 games in a row, Gear left professional baseball and accepted a job with Kaw Milling Company selling Life O’Wheat breakfast cereal. Years later, Gear was quoted as saying, “I have served my time in baseball and when I retired in 1914, I retired for good. I am selling Life O’Wheat now and I am trying to forget everything I ever knew about baseball.”25 In 1923, a group of Topeka investors who knew nothing about the baseball business approached Gear seeking advice. They had secured Topeka’s franchise in the Class D Southwestern League and admitted they knew nothing about running a ball club. Gear was free with his advice and after a few meetings, they prevailed on Gear to serve as the team’s field manager. He had been out of baseball for nine years, but he accepted the job for one year. The team was a success, finishing third, and Gear’s second career in baseball had begun.

Prior to the next season, Gear relinquished the manager’s job to veteran Barney Cleveland,26 as the Topeka franchise and three others moved from the Southwestern League to the eight-team Class C Western Association. Gear was elected Vice-President of the League.27 He bought stock in and became a part owner of the Topeka club. The 1924 season was a costly one for Topeka’s owners as the franchise’s losses were significant. In order to keep baseball alive in Topeka, Gear revived the old Class D Southwestern League, moved Topeka into it and accepted the league presidency while continuing to serve as vice-president of the Western Association.

In 1926, the Class A Western League ousted its president and hired Dale Gear to replace him. Also that year, the National Association of Minor Leagues tapped Gear to serve as its sole representative on the all-important baseball rules committee. At the national meeting held in New York, the question of pitchers’ use of resin on their fingers arose. The delegates from the National League favored the use of resin; the delegates from the American League did not. It fell to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and Dale Gear to break the tie. Gear, being a former pitcher, favored the use of resin and Landis concurred. As a result, the resin bag became a staple on every pitcher’s mound.28

In 1927, still serving as President of the Western League and the now-defunct Southwestern League, Gear reorganized the Western Association as a Class B league and became its president. Thus, he became president of two active minor leagues and one inactive.29 In addition, he was appointed a member of the national board as a representative of the Class C minor leagues.30 Gear served as the president of the Western Association until it folded after the 1932 season. He was appointed to the arbitration board and later the executive committee of the National Association of Professional Leagues. After the 1935 season, and after 10 years at the helm, he resigned as President of the Western League, finally ending his career in baseball.

Gear was viewed as a man of good judgment and fair play who wore many hats in baseball as a player, manager, owner and executive. On a summer’s day in St. Paul back in 1902, manager Gear had been called on to serve in another role. The umpire did not show for the Blues’ American Association game against the Saints and Gear, a man respected by all for his honesty and integrity, volunteered for the job. His Blues won the game, 3-1, and even the local newspaper reported: “Gear gave the best exhibition of good umpiring ever seen at Lexington Park. He was fair and impartial and never remembered during the game that his team was fighting to go home with a win.”31

Dale Gear’s record in baseball earned him the respect of club owners and players and he was proud to have served closely with Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in his efforts to clean up baseball and make it a better game. In later life, he served four terms as a Shawnee County, Kansas, Commissioner. He was married to Myrtle Benham in 1902 and divorced in 1913. They had no children. He married Pearl Varner in 1915 and they had one child, Dorothy Dale (Gear) Maryanski. Dale Gear died September 23, 1951, at the age of 79 and is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Topeka.32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Steve Rice and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used the following references.

Books

Niese, Joe, Zack Wheat, The Life of the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2021)

Richter, Francis C., Richter’s History and Records of Baseball, (Philadelphia, PA: Francis C. Richter, 1914)

Ritter, Lawrence S., The Glory of Their Times, (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2010), originally published 1966.

Websites

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

Baseball-Reference.com

Newspapers.com

Notes

1 Charles Saulsberry, “Red Stockings Come Into Own,” The Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, OK, February 26, 1940: 13.

2 Charles Saulsberry, “Dale Gear Led The Run of ’94,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 27, 1940: 14.

3 Charles Saulsberry, “Dale Gear Slips City a ‘Curve,’” The Daily Oklahoman, March 1, 1940: 12.

4 Charles Saulsberry, “$1,000 Strike Makes Gear, Breaks Purcell,” The Daily Oklahoman, March 2, 1940: 11.

5 Charles Saulsberry

6 “Dale Gear’s First Game in the East,” The Garnett Plaindealer and Anderson County Republican, Garnett, KS, August 21, 1896: 2.

7 “Dale Gear’s League Record,” Lawrence Daily Journal, Lawrence, Kansas Oct 2, 1896: 4.

8 “Dale Gear’s League Record,” Cleveland World, Cleveland, OH, September 23, 1896, as quoted in the Lawrence Daily Journal, Lawrence, KS, Oct 2, 1896: 4.

9 “Won By the Blues,” Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, September 19, 1898: 5.

10 “Our Pennant,” Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, September 21, 1898: 5.

11 “Secretary Dale Gear,” The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, June 24, 1901: 3.

12 “Senators Win Again,” Washington Evening Star, Washington, DC, May 15, 1901: 9.

13 August 20, 1901, Baseball Reference.com

14 “Red Sox Swept By Lowly Royals,” Austin American-Statesman, Austin, TX, August 11, 2006: C5.

15 Baseball Reference.com

16 “End of Post-Season,” St. Joseph News-Press, St. Joseph, MO, October 5, 1903: 7.

17 “Dope For the Fans,” Nashville Banner, Nashville, TN, September 7, 1905: 6.

18 “Dale Gear Will Quit,” The Evening Star, Independence, KS, February 1, 1906: 1.

19 “Malarkey Signs Dale Gear,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, Little Rock, AR, June 23, 1907: 13.

20 “Zach Wheat, Old Southern Leaguer, Says Dale Gear Showed Him How,” The Times-Democrat, New Orleans, LA, June 15, 1910: 1.

21 “Oklahoma City Seeking Gear,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis, MO, September 18, 1910: 2b.

22 “Austin Club Breaks Record,” The Times, Shreveport, LA, August 17, 1911: 7.

23 “The Texas League Race,” The Houston Post, Houston, TX, August 13, 1911: 17.

24 “Dale Gear to Lead Kaws Next Year?” The Topeka Daily Capital, Topeka, KS, September 17, 1911: 1.

25 “Western Prexy Vet in Baseball,” The Nebraska State Journal, Lincoln, NE, January 19, 1926: 4.

26 “Barney Cleveland to Pilot Topeka Kaws,” The Hutchinson News, Hutchinson, KS, December 12, 1923: 15.

27 “Elect W. A. Officers Here,” Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, November 5, 1923: 10.

28 “To Use Resin in Majors in 1926,” The Des Moines Register, Des Moines, IA., January 30, 1926: 30.

29 “57 Varieties of Jobs Keep Dale Gear, President of Two Baseball Loops, Plenty Busy,” Springfield Leader and Press, Springfield, MO, February 19, 1928: 13.

30 “57 Varieties of Jobs Keep Dale Gear, President of Two Baseball Loops, Plenty Busy,” Springfield Leader and Press, February 19, 1928: 13.

31 “Blues Take Third,” St. Paul Globe, St. Paul, MN, July 17, 1902: 5.

32 “Dale D. Gear Dies at Age 79,” The Topeka Daily Capital, Topeka, KS, September 24, 1951: 1.

Full Name

Dale Dudley Gear

Born

February 2, 1872 at Lone Elm, KS (USA)

Died

September 23, 1951 at Topeka, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.