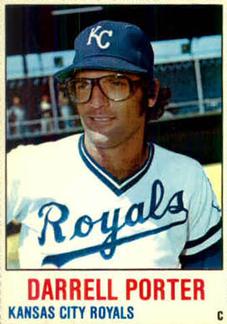

Darrell Porter

St. Louis Cardinals catcher Darrell Porter leapt into the waiting arms of relief pitcher Bruce Sutter after the last out of the 1982 World Series. Fireworks lit up the sky above Busch Stadium. Fans roared with delight; many jumped onto the field and joined the celebration.

St. Louis Cardinals catcher Darrell Porter leapt into the waiting arms of relief pitcher Bruce Sutter after the last out of the 1982 World Series. Fireworks lit up the sky above Busch Stadium. Fans roared with delight; many jumped onto the field and joined the celebration.

Porter, voted the Series MVP, said afterward, “I didn’t know I’d ever feel this good again. I didn’t think I’d ever be in this position.” He added, “What happened in the past is in the past. I’ve got a wonderful wife, a beautiful little girl 6½ months old. I haven’t had a drink in 2½ years. I haven’t had any pot or any pills, either.”1

Maybe Porter had conquered his demons. Maybe he no longer needed alcohol or other recreational drugs. Maybe he could put that rehab stint in 1980 behind him and just focus on baseball and family. He and his loved ones hoped, and sometimes prayed, that he could.

The four-time All-Star played another five seasons. He retired in 1987 with 188 home runs and 826 RBIs. Whitey Herzog, who managed Porter both in St. Louis and for the Kansas City Royals, said, “He played for me eight years, and we won four times, so he had to be a pretty good player.”2

Porter wrote a book published in 1984 titled Snap Me Perfect!: The Darrell Porter Story. He admitted that staying sober wasn’t easy. “I still have moments when I don’t think I can make it. … Sometimes, I wish the Lord would snap me perfect.”3

Darrell Ray Porter was born on January 17, 1952, in Joplin, Missouri, located in the state’s southwest corner. His father, Raymond, hailed from Gracemont, Oklahoma, a town of just a few hundred people. Ray met Twila Mae Conley at a square dance in 1947. The two fell in love at first sight. “He looks like Clark Gable!” Twila Mae said after taking one look at the athletic, dark-haired Ray.4 Soon after, they were married. Ray found a job driving for United Transport in Joplin.

The youngest of four Porter children, Darrell began playing organized baseball as a Little Leaguer. Within a few years, he grabbed a catcher’s mitt, a chest protector, and a mask. “It was when I began to concentrate exclusively on catching that I really blossomed,” Porter wrote. “Even in those days, I hustled my butt off behind home plate. I was a fiery catcher.5

Darrell followed his siblings to Southeast High School in Oklahoma City. He went out for football, basketball, and baseball. Football scouts liked his strong throwing arm. Nearly 40 universities — including Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Southern Methodist — wanted him to play quarterback. Agents, though, said that Porter could expect a $100,000 signing bonus — or more — if he chose professional baseball. The Milwaukee Brewers drafted Porter fourth overall in the June 1970 amateur draft.

The Brewers didn’t give him $100,000. They offered $70,000 and assigned Porter to the Clinton (Iowa) Pilots of the Class-A Midwest League. “We feel this young man is our number-1 catcher of the future,” Milwaukee general manager Marvin Milkes said after the signing.6

Milkes told Porter to stop off in Baltimore for a couple of days before reporting to Clinton. The Brewers were playing a series against the Orioles. One look at that major-league clubhouse, and the 18-year-old prospect felt shocked. He saw ballplayers drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. “The illusions I had always cherished about clean-living jocks were shattered in that clubhouse for good,” Porter lamented.7

His rookie season in pro ball didn’t get much better after that disappointing introduction. Porter batted just .200 in 185 at-bats. Like many young players, he struggled to hit professional changeups and curveballs. And the long season tired him out. And, finally, Porter took a drink. He put away four bottles of beer that first night. The rest of the season, he went out a few nights every week. The drinking helped him relax.

Porter reported back to Class-A ball in 1971, this time to Milwaukee’s new Midwest League affiliate, the Danville (Illinois) Warriors. His sophomore season went much better than his freshman campaign. He hit 24 home runs, drove in 70 runs, and batted .271 as a 19-year-old. The Brewers called him up in September. Porter made his major-league debut on September 2 and went hitless in three at-bats against the Kansas City Royals at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. The Brewers won 1-0 behind Marty Pattin’s five-hit shutout. A few nights later, at home against the California Angels, Porter collected his first major-league hit, a single off Angels starter Tom Murphy that scored Jose Cardenal. Later, he added a sacrifice fly. The Brewers beat the Angels, 6-4. Porter batted .214 with two homers and nine RBIs in 22 games with Milwaukee.

Over the offseason, Porter met Teri Brown. He was quickly smitten, and the two began dating. Soon enough, they set a wedding date for May 30, 1972. Porter also started using Quaaludes, a barbiturate. “They eventually became my drug of choice,” Porter said. “With a ’lude, nothing bothered me.”8

The Brewers expected Porter to share starting catching duties with veteran Ellie Rodriguez in 1972. But major-league pitching still baffled Porter. He played in 18 of Milwaukee’s first 25 games and batted just .125 with one home run and two RBIs. The Brewers sent him to the team’s Triple-A affiliate in Evansville, Indiana. “We felt that major-league pitching was just a little too tough for him,” said Frank Lane, who took over the GM duties in Milwaukee after the 1970 season. “So we went sent him down to the minors to develop more batting experience.”9

Porter hit just .216 with 13 home runs and 45 RBIs as an Evansville Triplet. He did not get a late-season call-up to the big club but looked forward to establishing himself as a regular in 1973 and joining other talented prospects, including infielder Pedro Garcia and outfielder Gorman Thomas.

The Brewers also counted on quality veterans like first baseman George Scott, third baseman Don Money, outfielder Dave May, and pitcher Jim Colborn. Ellie Rodriguez broke his hand in spring training, making Porter the starting catcher as a 21-year-old with a .175 batting average in 40 big-league games. When Rodriguez returned, the two shared duties behind the plate.

Porter cut down his swing in 1973. “I have natural power, so I don’t have to cut hard,” he told a reporter in June.10 The change in approach worked. Porter smacked 16 homers, drove in 67 runs, and batted .254 with a .363 on-base percentage. The Brewers backstop tied for third in the AL Rookie of the Year voting, along with pitchers Steve Busby of the Royals and Doc Medich of the Yankees. The Baltimore Orioles’ Al Bumbry won the honor, while Pedro Garcia, Porter’s Milwaukee teammate, took second. The Brewers finished 74-88, in fifth place in the AL East.

The Brewers traded Ellie Rodriguez in the offseason. Porter went on to make his first AL All-Star team. He said that Money, Scott, and Briggs deserved the honor more than he did. Even so, he added, it was “the greatest thing that has ever happened to me.”11

Porter, batting .272 at the midsummer break, struggled as the season wore on. He finished at .241 and hit 12 home runs. The Brewers ended up 76-86, once again in fifth place. A late-season incident put a damper on Porter’s first All-Star campaign. Near the end of a twin bill against the Cleveland Indians on September 23 at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, Porter jumped onto the top of the dugout and punched a fan who had been razzing him for several innings.

“I’d rather not say anything about what happened,” Porter said afterward. Brewers manager Del Crandall told reporters, “The fans were on him all night. It was one of those quick-reaction things. It certainly didn’t take him long to get up there (to the top of the dugout).”12 Newspapers across the country printed photos of several Brewers restraining Porter. Baseball fined Porter and suspended him for three games.

Porter put together another solid year in 1975. He slugged 18 home runs and drove in 60 runs. His batting average slipped to .232 but, thanks to 89 walks, he raised his on-base percentage over the previous year, from .326 to .371. Even so, Milwaukee still could not get into the pennant race and fell to fifth place for the third straight season, this time with a 68-94 mark. The Brewers fired Crandall in late September.

Porter’s 1976 season turned into a mess. He batted only .208 with 5 homers and 32 RBIs. Off the field, his life spiraled out of control. Porter’s marriage to Teri ended in divorce, and his drug problems continued. A friend introduced him to cocaine at a party. “I wanted to fit in, really fit in,” Porter said. “And coke did that for me.”13 He wrote that he contemplated suicide but not seriously. “There was always pot and Quaaludes, beer, cocaine to dull the agony of living,” he wrote.14 The team also had spiraled downward and muddled through a 66-95 campaign, in last place in the AL East.

Porter’s career in Milwaukee ended December 6, 1976. The Brewers dealt him and Colborn to the Royals for infielder Jim Wohlford, infielder Jamie Quick, and a player to be named later (Bob McClure). Porter hoped for a new start in Kansas City and admitted that “my mind just wasn’t 100 percent on baseball” the previous season.15 When he arrived at the team’s spring-training facility in Fort Myers, Florida, he noticed some changes from his Brewers days, such as the team camaraderie and family atmosphere. “There’s a feeling of togetherness that we didn’t have in Milwaukee,” Porter said.16

Porter joined a franchise that began playing in the American League as an expansion club in 1969, two years after the Kansas City Athletics left for Oakland. The team finished above .500 in just its third year of existence (85-76 in 1971) and won a division title in 1976, going 90-72 before losing to the New York Yankees in the AL Championship Series.

Kansas City boasted talented players like third baseman and future Hall of Famer George Brett, first baseman John Mayberry, second baseman Frank White, and outfielders Amos Otis and Al Cowens. The strong starting pitching staff included Dennis Leonard, Paul Splittorff, and Colborn.

Porter got off to a solid start with his new team, winning Royals Player of the Month honors in April with a .365 batting average, one homer and 11 RBIs. Kansas City went 11-8 in April but stumbled through a 10-15 mark in May. The Royals finally got hot as the weather warmed and cruised to a 102-60 record by season’s end, the best mark in baseball. And then they lost again to the Yankees in the playoffs. Porter batted .333 (5-for-15) during the postseason after hitting .275 with 16 home runs and 60 RBIs in 130 regular-season games.

Kansas City celebrated another division crown in 1978. Porter ripped 18 homers, drove in 78 runs and hit .265 with a .358 on-base percentage. The 26-year-old catcher earned a spot on the AL All-Star team for a second time and plenty of admiration from Herzog. On June 4 Porter smacked two triples, a double, and two singles in leading Kanas City to a 13-2 pasting of the Chicago White Sox. “That might be as fine as I’ve ever seen a guy have,” Herzog said. “He swung hard at every pitch and hit the ball well to all fields.”17

Once again the Yankees ended Kansas City’s hopes for postseason glory in the ALCS. Porter went 5-for-14 for a .357 batting average and drove in three runs against Yankees pitching in October. Porter told Sports Illustrated that not much separated the Yankees and the Royals. “But that small difference,” he said, “is what makes KC a good team and New York a great one.”18

Porter spent his offseason in the fast lane. “I went wild,” he said.19 Then he stepped on the brakes and posted the best numbers of his career. Early in the 1979 campaign, when Porter was batting .379, Herzog declared him “the best catcher in the league.”20

By mid-June Porter carried a .305 average with 9 home runs and 53 RBIs. He beat out popular Boston Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk for starting catcher on the AL All-Star team. He finished with career highs in most offensive categories, including home runs (20), RBIs (112), batting average (.291), runs scored (101), on-base percentage (.421), and slugging percentage (.484). He led the AL with 121 walks and played in 157 games. The writers voted him ninth in the MVP race. He might have finished higher, but the Royals slumped to 85-77 and slipped to second place, missing out on the playoffs for the first time since 1975.

Over the winter, Porter settled into another self-destructive routine. “Get up and make coffee, do a Quaalude, drink beer, sniff cocaine, and smoke cigarettes,” he wrote.21 Finally, in the spring of 1980, he checked into The Meadows drug treatment center in Arizona. Royals general manager Joe Burke told reporters, “Darrell Porter has a very confidential and personal problem. I cannot betray his confidence, but I don’t expect him to be back with us until he has had treatment for his problems.”22

After a six-week program, the catcher returned to Kansas City, and to a new manager. The Royals had fired Herzog and signed Jim Frey as the new skipper. Despite some nervousness, Porter started his season strong. He lifted his batting average above .300 at one point and was still hitting .274 when Orioles manager Earl Weaver named him to the All-Star team as a reserve. The Royals earned another division title, finishing 97-65, 14 games better than the runner-up Oakland A’s. Brett led the way for Kansas City with his .390 batting average, the highest season-ending average since Ted Williams hit .406 for the 1941 Boston Red Sox. Porter batted .249 with 7 homers and 51 RBIs.

This time the Royals finally knocked off the Yankees in the ALCS, sweeping them in three games. They faced the Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series. Porter, who hit just .100 against New York (1-for-10), batted only .143 in the fall classic as Philadelphia won in six games.

Over the offseason, Porter remarried. He also signed a five-year, $3.5 million contract with the Cardinals. The deal made sense for Porter and his bride, Deanne. They’d be going to a new city but one just a few hours away from Kansas City, and St. Louis had hired Porter’s old boss, Whitey Herzog, as manager.

Then, the Cardinals made life tough for their new player. They traded popular All-Star catcher Ted Simmons to Milwaukee. “From day one, a few of the Cardinals fans took an instant dislike to me,” Porter wrote. “This vendetta by the St. Louis fans really hurt me. Things got worse and worse, and gradually it affected my game to the point that I hated come to the stadium.”23

Porter began the season in a slump that lasted for months. He batted just .173 through April and May. On June 12, 1981, the players went on strike. As the work stoppage wore on, Porter did some fishing. One day, he drank a beer and then drank a few more. “An alcoholic (and a drug addict for that matter) is never cured,” Porter wrote. “All his life, he is only a recovering alcoholic/addict. One taste of beer, one snort of coke (or whatever), can put him back into the gutter.”24

The season restarted on August 10 in a split-season format. Porter played in just 61 of the team’s 102 total games. He batted .224 with 6 home runs and 31 RBIs and did not top the .200 mark for good until August 23. The Cardinals, who stood in second place with a 30-20 record when the strike began, also wound up as division runner-up in the second half (29-23) and missed the postseason.

Porter enjoyed a slightly better year in 1982. He ripped 12 homers, drove in 48 runs, and batted .231. St. Louis won the division with a 92-70 mark and beat the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS. Porter hit .556 (5-for-9) and walked five times for a .714 on-base percentage against Atlanta. Next, the Cardinals met the Milwaukee Brewers in the World Series. Porter batted .286 (8-for-28) with one homer and five RBIs; St. Louis won the Series in seven games. “Bruce (Sutter) and I grabbed one another and did a victory polka”25 after Gorman Thomas struck out to end the Series, Porter wrote.

Maybe Porter could extend that postseason glory into 1983. He did put up his best numbers as a Cardinal — 15 homers, 66 RBIs, a .262 batting average, and a .363 on-base percentage. St. Louis, though, finished in fourth place with a record of 79-83. A frustrated Porter spoke to reporters about the team’s struggles and his ongoing battles with addiction. “I guess I keep talking about it because it might be some kind of safeguard against me doing it again,” he said, but added, “I could get back into drugs again and no one would know, because they didn’t know before.”26

St. Louis improved a bit in 1984, going 84-78 and winding up third in the NL East. Porter, though, once again struggled to find any offensive consistency. He hit 11 homers with 68 RBIs but batted a modest .232 in 127 games. Maybe the veteran catcher had started to wear down at age 32. “Darrell Porter was just not producing,” Herzog wrote. “He’d gotten his life turned around after kicking his drug habit, but in the process, he’d lost his aggressiveness.”27

Porter split catching duties with Cardinals prospect Tom Nieto in 1985 and batted .221 with 10 homers. St. Louis beat the Los Angeles Dodgers in the NLCS and met Porter’s former team, the cross-state Royals, in the World Series. Porter managed two hits in 15 at-bats. St. Louis released him shortly after the Series ended. He signed a two-year deal with the Texas Rangers.

Porter got into 68 games, hit 12 homers, and batted .265 in 1986. The Rangers finished in second place with an 87-75 record. The following year, he played 85 games, batted .238, with 7 homers and 21 RBIs. The Rangers did not offer Porter a contract for the 1988 season, making him a free agent. No other team made him an offer.

In retirement, Porter began to speak about his Christian faith and his struggles with drug addiction. He dabbled in real estate and several businesses and also hosted a weekly radio show in Kansas City, with hopes of joining the Royals radio booth. Along with a friend, Bill Stutz, Porter worked with Enjoy the Game. Stutz founded this youth program, which encourages good sportsmanship at athletic events and a positive environment for students and parents. “What it teaches is respect for your teammates or peers, the coaches or teachers, and to respect authority and the rules and to do what’s right,” Porter said.28

On the worrisome side, Porter’s weight ballooned from about 225 pounds to nearly 300. He died on August 5, 2002. He had driven from his house in the Kansas City suburb of Lee’s Summit to a park in nearby Sugar Creek. His body was found next to his car that afternoon. He was 50 years old. The chief of the Sugar Creek Police Department said Porter’s car went off the road and hit a tree stump. Police theorized that Porter tried to push the car off the stump and “the heat got to him”29 on a 97-degree day. No foul play was suspected.

A few days later, the Kansas City medical examiner, Dr. Thomas Young, reported that Porter had cocaine in his system, “typical of someone who uses (cocaine) recreationally.” Young said that Porter did not die from an overdose, but from excited delirium, which causes “behavior that is agitated, bizarre, and potentially violent,” and stopped his heart.”30 He left behind his wife, Deanne, and three children, Lindsey, 20; Jeff, 18; and Ryan, 14.

Nearly 1,000 people attended Porter’s memorial service on August 9 at Noland Road Baptist Church in Independence, Missouri. A smaller service was also held that day at First Baptist Church in Raytown, Missouri. Longtime friend and former Royals teammate Jerry Terrell said, “So, all I’ve got to say is this: Darrell, I love you, man. I really miss you. Thanks for the memories.”31

Last revised: March 9, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Porter Delivers the Goods,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1982: 28.

2 Rick Hummel, “Cardinals Family Mourns Again After Porter’s Death,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 7, 2002: 38.

3 Darrell Porter and William Deerfield, Snap Me Perfect! The Darrell Porter Story (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Newson Publishers, 1984), 219.

4 Snap Me Perfect, 26.

5 Snap Me Perfect, 40.

6 Tom Flaherty, “Porter Rides Around and Learns,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), August 3, 1970: 29.

7 Snap Me Perfect, 64.

8 Snap Me Perfect, 87.

9 Associated Press, “Scoreless Streak at 19,” Fond du Lac (Wisconsin) Commonwealth Reporter, May 22, 1972: 26.

10 “Porter Puts It All Together,” Wisconsin State Journal, June 10, 1973.

11 AP, “Surprise! Brewers’ Porter Is an All-Star,” Wausau (Wisconsin) Daily Herald, July 19, 1974: 18.

12 AP, “Brewers Split in Battle for 4th,” Green Bay (Wisconsin) Gazette, September 24, 1974: 23.

13 Snap Me Perfect, 103.

14 Snap Me Perfect, 112.

15 Joe McGuff, “Porter Finds Royals Better Tippers than Brewers,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1977: 7.

16 Ibid.

17 AP, “Darrell Porter Has a Royal Day,” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), June 5, 1978: 15.

18 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: William Morrow, 2000), 534.

19 Snap Me Perfect 139.

20 Snap Me Perfect, 140.

21 Snap Me Perfect, 155.

22 AP, “Everybody Wonders Just What’s Wrong with Darrell Porter,” Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), March 18, 1980: 27.

23 Snap Me Perfect, 237.

24 Snap Me Perfect, 238.

25 Snap Me Perfect, 251.

26 Mark Whicker “Baseball’s Newest Spy Scheme a Shot in the Dark,” Hartford Courant, June 11, 1983: 98.

27 “Baseball’s Newest Spy Scheme,” 154.

28 Rob Rains and Alvin Reid, Whitey’s Boys: A Celebration of the ’82 Cards World Championship (Chicago: Triumph, 2002), 88.

29 Heather Hollingsworth, “Cause of Porter’s Death Not Yet Available,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), August 7, 2002: 27.

30 AP, “Autopsy Shows Cocaine in Darrell Porter’s Body,” Courier-Journal (Louisville), August 13, 2002: 36.

31 Amy Shafer, “Memorial Honors Porter’s Friendship,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, August 10, 2002: 27.

Full Name

Darrell Ray Porter

Born

January 17, 1952 at Joplin, MO (USA)

Died

August 5, 2002 at Sugar Creek, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.