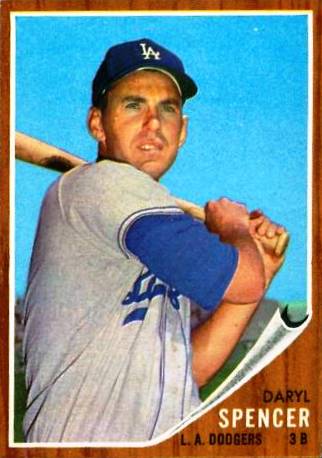

Daryl Spencer

In four years of high school and two in college, Daryl Spencer won just one varsity sports letter. In his first season of Ban Johnson baseball, he hit about .260. Not a single major league scout even nodded toward him until well into his first season of professional baseball.

In four years of high school and two in college, Daryl Spencer won just one varsity sports letter. In his first season of Ban Johnson baseball, he hit about .260. Not a single major league scout even nodded toward him until well into his first season of professional baseball.

Yet he was in a major-league starting lineup for eight Opening Days. On consecutive days in 1958, he and teammate Willie Mays each hit two home runs and in three straight seasons he had a dozen game-winning hits. Little wonder he was the boyhood idol of Joe Morgan, who grew up in the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Area.

Daryl Spencer, along with a brother and sister, grew up in his native Wichita, Kansas, a son of the Depression. His dad, an oilfield drilling contractor who played baseball in pastures where cow patties served as bases, had streaks of his own. He once drilled 13 successive dry holes. Money was tight in the Spencer household. Daryl believes the family may have set a record by living at four different addresses on the same street, moving every few months as their rented houses were sold.

But almost everyone had a personal version of 13 dry holes in the mid-Kansas of the 1930s. Wichita was on the fringe of the Dust Bowl and close enough to Oklahoma that refugees fleeing to California drove in caravans through town each day. Short paychecks and stretched budgets were common. But Spencer family economics worsened during Daryl”s junior year in high school when his dad died unexpectedly. “Something to do with his liver,” the son recalls. “He didn”t have a drinking problem or anything, and it probably could be cured today.” But the loss was heart-breaking and his dad was his first thought when he walked into the Polo Grounds with tears in his eyes as a rookie near the end of the 1952 season.

Baseball encyclopedias say Daryl was born in 1929, but he says he is actually a year older, born July 13, 1928. “Everyone did that in baseball. Used to be you”d hit 32 and they”d think you should retire. Now they play into their 40s but that wasn”t true in the old days.”

“The old days” in his case were from 1952 until 1963. The record shows a .244 batting average in 1,098 major league games. But that seems to miss the clutch hitting and power part, Spencer”s stock in trade. He was usually hitting in the middle of the lineup, placed there to drive in runs. In 1956 the Associated Press reported:

“Spencer, the long ball hitter from Wichita, Kan., only a .244 batter, has produced the big base hits in three of the Giants” first nine triumphs. He had two game-winning blows against Philadelphia, a single in the seventh inning and a home run in the sixth. And he also broke up the May 2 marathon against the Chicago Cubs with a sacrifice fly in the 17th frame.”

Tall and lanky like his own boyhood idol, Marty Marion, but 15 pounds heavier, he hit 260 home runs in 10 major league seasons and almost seven in Japan.

In 1958 he hit the first major league home run on the West Coast against Don Drysdale of the Dodgers. “The shortstop with a fullback build snapped a home run into the pavilion at the 364 foot mark and, engulfed in a triumphant smile, slowly and with great dignity circled the bases, his gleaming spikes carrying him along the first home run trail in San Francisco major league history,” said the San Francisco News.

It was a surprise to Daryl to learn he received a standing ovation. “”No kidding?” he said afterward in the clubhouse. “A standing ovation? I didn”t notice. I was so darn happy I didn”t notice anything but the ball sailing into the crowd,”” he told writer Bob Stevens.

Spring and early summer were the Spencer months. “I didn”t do very well in the heat. But so long as it was cool, I was fine.” As if to prove it, when he was traded to the Cardinals in the winter of 1959, he became the first player to hit three home runs in a spring training game at huge Al Lang Field, where the Redbirds and Yankees trained. The headline the next morning read, “In Bat Show at Lang It”s Spencer 10, Yanks 3.”

The Kansas native”s route to the major leagues was direct — once he started. He didn”t make his high school team until his senior year and even then didn”t have a position to play every day, moving around the infield. But he led the team with a .426 batting average and 27 runs batted in. The East High School Blue Aces compiled a 21-1 record and won the state championship. At what now is Wichita State University, freshmen were not eligible to play in 1947. And playing ping-pong or hearts at the Men of Webster fraternity house when his 8 a.m. psychology class was meeting kept him academically ineligible as a sophomore.

But he played well enough in the summer of 1946 to help his Junction City Ban Johnson team win the league title and state championship. While he hit .260 with 29 RBI, he still wasn”t showing power. He had only one home run. In 1947-48 he performed with a powerful semi-pro team, the Boeing Bombers. His performance as an all-star with Boeing both seasons opened the door to his professional career.

Boeing”s manager was Clarence (Red) Phillips who had a 4-4 record as a Tiger pitcher in the middle 1930s. “Red became kind of a father figure to me,” Daryl recalls. When Phillips returned to his boyhood home in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, to manage the city”s independent class D Sooner State League team in 1949, he took Spencer and four other Bombers with him as the club”s nucleus.

To that point, no scout had approached Spencer. But in Pauls Valley, they swarmed. “The Cardinals scouted me and I kind of hoped they”d sign me,” Spencer says. “I was a Cardinal fan growing up and we”d listen to them on the radio. They were the closest big league team to Wichita. My dad went to the World Series there in 1942 and had brought back some memorabilia for me that I really treasured.”

There was plenty of reason for the scouts” interest. Spencer owned the Sooner State league. Suddenly he had power, setting what was then a league record with 23 home runs even though the official ball was a Worth, “which everyone knew was the deadest ball in the game.” He batted in 112 runs, second in the league, and compiled a .286 average, eighth best.

After top scout Mel Ott looked carefully, the Giants paid $10,000 and five players from their Lawton team for Spencer, assuring Pauls Valley of a cadre of players the following year. Spencer had earned only $150 a month that summer plus $1.75 a day in meal money. But the team made good on an oral agreement to pay him part of the selling price if his contract was sold. They gave him $1,000, and he spent $250 on an engagement ring for Eleanor Meitzner in Wichita. The couple celebrated 55 years of marriage in 2005.

His rise through the Giant organization was sure. He started slowly at Sioux City in the class A Western League in 1950. After three weeks he was hitting only .180 when Ott, also the Giants” hitting instructor, came to town. “He watched me for a couple of games and said, “Kid, you”ve got the good stroke and everything. You”re just worrying. Relax. You”ve got the job.” It just seemed like I turned it around from then. It was just a matter of relaxing and knowing I had the job.

“I had 99 RBI in that league and I never will forget in the next-to-last game of the season. I got a base hit up the middle and Ray Katt was on, and he didn”t even score for me to get a hundred,” Spencer remembers, laughing.

He moved up to AA Nashville and AAA Minneapolis in successive years. In four minor league seasons he made the all-star team at each stop. After hitting .294 with 80 RBI and 27 home runs at Minneapolis, he went to New York at the end of the American Association season on September 17, 1952, going 0 for 3 against Bob Rush in a 2-0 win over the Cubs. After three more trips to the plate, he had his first major league hit, a triple good for two RBI, against the Phillies on September 26 off Steve Ridzik. Two days later he was in the starting lineup, getting three hits off Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts as Roberts won his 28th game of the season.

Leo Durocher managed Spencer when he arrived in the majors. “I was a dead pull hitter when I got there. In AAA, they”d even pull a shift on me, moving the second baseman into the hole behind the base. But I still could usually hit. With the Giants in 1953 I was off to a real good start and was hitting .270 with 14 home runs by June 1. But back in New York, Durocher said, “Kid, start thinking about hitting to right field.” That threw me completely off. The Polo Grounds was just built for me. I was being talked about with Junior Gilliam as rookie of the year and was really helping the Giants. But as I started trying to put the ball to the right side, my average dropped to .208 and I hit only six more home runs… In the long run, learning to hit to all fields probably helped me stay in the big leagues.

“The secret to hitting is to wait, wait, wait. There”s nothing better than being in a hitting groove, better than good sex. As soon as the ball leaves the pitcher”s hand, you know what the pitch is and where it”s going to be. The ball looks as big as a grapefruit. I”d stand at the plate and decide what I”ll hit.

“But it”s just the opposite when you”re in a rut. The ball is on you before you know it and it looks like a pea.”

By 1954, Spencer had a new job as a soldier. He had been draft-exempt for a time, working as a draftsman at a Grumman defense plant on Long Island during the off-season, a job arranged by the Giants. By the time he was drafted, the Army-McCarthy congressional hearings were being nationally televised. Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy not only was hunting Communists, but railing against favored treatment of athletes in the service. “I finished basic training at Fort Riley, but then nobody wanted me because of the hearings. Finally some colonel at Fort Sill said he”d take me and he put me in charge of the baseball team.”

While in the Army, his old semi-pro club in Wichita asked him to play in the National Baseball Congress state and national tournaments. He made the 250-mile trip from Oklahoma in a plane sent by Boeing, often after an afternoon game with his service team. He then would play in Wichita, hop on a 1:30 a.m. train for Duncan, Okla., then hitch hike to Fort Sill before Reveille. He was never late, he says.

The schedule didn”t hamper his play. Boeing won consecutive national non-pro championships and Spencer was named most valuable player in the 1955 national tournament. That same summer he was MVP in the first Global World Series for non-professional teams at Milwaukee.

His 21-month military career did cost him one coveted chance: a spot on the Giants” 1954 world championship team. However, he took a short leave from the Army to see the Giants win three games in their four-game sweep of the Cleveland Indians. “Even thought I didn”t play, they voted me a $2,000 World Series share. That doesn”t seem like much now, but each player only got about $5,000,” he recalls. It also equaled the amount he received for nearly two years of Army service. Even though he played on later teams that came close, he never made it to a post-season championship series.

When he returned from the Army in 1956, Bill Rigney was the Giants” manager. While Durocher helped make him a more complete hitter, Rigney was his favorite manager. The two roomed together in Spencer”s rookie year, when Rigney was still playing.

“I could really communicate with him. He used to coach third base a lot and many times he would pick up a pitcher”s motion from his position in the coaches” box and relay to me the type of pitch to expect. I was pretty good at doing that myself, but I”m not the one to refuse a little help along the way,” Spencer continued. His knack for reading pitchers and knowing what pitch was coming later helped him greatly in Japan. “I had a field day over there,” he said.

Daryl also roomed with Alvin Dark, captain of the Giants and the regular shortstop. “He taught me more about baseball than anyone else,” Daryl says. At night the two would lie in their beds, putting off sleep while they talked about the game, a personal tutorial.

The 1958 season probably was Spencer”s best in the big leagues. He hit .258, had 17 home runs, and batted in 74. He was a near-miss for a reserve spot on the National League all-star team. Ernie Banks was the starter, as usual, but the Braves” manager Fred Haney skippered the all-star team and chose his own shortstop, Johnny Logan. “On June 23, all-star voting was going on and I was hitting .303 with 46 RBI, fourth in the league, and Logan was hitting maybe .240. To say the least I was extremely disappointed that I didn”t get selected.

“That just about did me in,” Spencer says, nearly half a century after losing to Logan. “I can”t blame a manager for taking his own guy, but for three weeks I just didn”t care about playing very much. The same thing happened again the next year.”

In 1959, the Giants were in the race until the final week and close to a pennant. Coach Herman Franks at times helped the team by stealing pitchers” signs, relaying them to hitters through the bull pen. Relief pitchers sitting with crossed legs might mean a curve was coming, for example. “You looked for any edge you could get,” Daryl says. “If we”d had steroids, we probably would have used them. It makes sense. It was legal and you did what you could to get an advantage.”

It had been awhile since anyone else had picked off signs for the hitters. “In late 1959 Franks came to the final game of a series with Milwaukee and (Giants manager Bill) Rigney got all the starting players together and he says, “You guys want to get the signs for this last home stand?” The Dodgers were coming in for a three-game series and even though we had a two-game lead with eight games to go, we all said, “Let”s do it!””

But Franks” help was never used. “[Pitcher] Al Worthington had gone to a Billy Graham crusade at San Francisco in 1958 and had become a born-again Christian. We were rooming together then, and that was all he could talk about, he was so thrilled. I finally started to avoid him because it was very uncomfortable for me to be around him even though we were great friends.

“But Worthington went to Rigney and protested. He thought stealing the signs would be cheating and against his Christian beliefs. So we didn”t. We”d been all pumped up and that really caused a huge letdown. It was like punching a balloon with a pin. The Dodgers swept the series and we finished third in the pennant race,” Daryl recalls.

That was his last year with the Giants. In the winter of 1959 he was traded to St. Louis, where he had dreamed of playing while fielding the tennis ball he bounced off the garage door as a kid. In May 1961 he was dealt to Los Angeles. The Cardinals were playing in Los Angeles when the swap was made. “I had batted against Sandy Koufax on my last day as a Cardinal. Then I took my stuff from the Cardinal clubhouse to the Dodgers” and had to face Bob Gibson that night,” he remembers. “That was a quick 0 for 8.”

Four days after the trade, he started a streak of winning three consecutive Ladies Night games with late-inning home runs. On June 3, 10 and 17 — all Saturdays — his long balls beat San Francisco, Philadelphia and Milwaukee. The homers against the Giants and Phillies were both ninth inning walk-off game winners, the third and fourth of his career.

Although he frequently played second base and third, shortstop was Spencer”s favorite position. “It was easier than second because all the plays are in front of you. I liked being able to see the catcher”s signs and know what was going to happen. Third base was a piece of cake. And first base? It was like taking a vacation,” he says. “It”s pretty hard to get hurt at shortstop because no one will slide into you from behind.”

He was injured at times, of course. Most hard-nosed players — as he describes himself — are. But the closest he came to serious injury was an exhibition against Cleveland when the Giants and Tribe were traveling together from spring training in Arizona. The game was in Nashville and Mike Garcia was pitching for Cleveland. “It was that time of day when either he was in the sunlight and I was in the shadows or I was in the sun and he was in the dark.

“I simply never saw the ball coming. I didn”t duck. He wasn”t throwing at me. It just got away from him. It hit me right here,” he says, pointing to his left cheek. It broke three teeth and required 20 stitches and a night in the hospital where Garcia came to check on him. But he was in the opening day lineup five days later and never suffered from it. “It didn”t make me gun-shy.”

Spencer actually hit a player himself. He gave Willie Mays a black eye with a thrown ball one day in a pre-game warm-up. But he kept his job.

Spencer”s final team was Cincinnati. The Dodgers had released him early in 1963, giving him the freedom to choose. He picked the Reds to stay in the National League. “I kept a book on all the pitchers, so I knew the league. If I”d gone to the American, which I had a chance to do, I”d have had to start over,” he explained.

It was there he met future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson. “I”d always worn number 20 and when I got to the Reds” clubhouse, that was Frank”s number. He asked me if I wanted it. I laughed and told him no, that he”d be around a lot longer than I would. But I thought the offer was pretty neat and me feel wanted”

The Ohio stop was productive but short-lived. He went four for five in his first game with the Reds and had a streak of four straight Saturday night games where he drove in the winning runs three times, twice in the ninth inning. In one of those games his hit beat ex-roommate, Sandy Koufax 1-0. The loss was a rare one that year for Koufax who compiled a 25-5 record with an earned run average of just 1.88.

On July 18, 1963 — his 35th birthday — he was given his unconditional release. “Some birthday present, hunh?” he asks. The club said it needed to trim payroll and in spite of his seven game-winning hits in two months, his $25,000 salary was a burden.

But the birthday present was not a financial disaster. In 1964 Spencer signed with Hankyu Braves of the Japanese Pacific League for $22,500. The Braves paid his travel expenses from the U.S., living expenses there and his taxes. Eventually he was earning $44,000 a year, tax-free, plus his traveling expenses to and from Japan.

They also called him “The Monster.” At 6″2″ he not only stood a head taller than his Japanese teammates, he hit and played like Godzilla. He twice was an all-star and in 1964 hit 36 home runs and had 95 runs batted in.

“When I first went over there, I learned you couldn”t tell them how to do things. You had to show them and prove it. They wouldn”t even try to break up a double play at second base. They”d usually take a right turn when they got close to second on a potential double play grounder. That really irritated me.

“We”re playing one day, the score is 0-0 and it”s the bottom of the eighth. They walked me to get to our clean-up hitter and I told Gordon Windhorn, my teammate who is on second, “If this batter hits a groundball, don”t stop on third. I”m gonna take out the guy at second.”

“Two pitches later he hits a ball to short, they threw it to second and I knock the second baseman down pretty good and he drops the ball. Windhorn comes around and scores. They call a time-out and argued for 30 minutes. In Japan it was customary for the umpires to get together and make a joint decision. They finally decided there was nothing illegal about my slide and we won the game 1-0.

“The next day, one of our guys slides and knocks down the second baseman and all of sudden the whole style of play is changed in Japan.

“Then I knocked down a catcher a few days later and won a ballgame and our guys started sliding like that. Even with all the home runs I hit, I”m more famous in Japan for my sliding,” he remembers.

But Spencer was denied the league home run title after a bizarre incident that may or may not have been an accident.

In 1965, Spencer had 32 home runs and Katsuya Nomura, a catcher for the Nankai Hawks, had 25. (Japan”s leading home run hitter, Sadaharu Oh, played in the Central League, not the Pacific with Spencer.) “Nomura”s team was way out in front so the only exciting thing was the home run race in the Pacific League. Then the batting coach comes to me before a game with my interpreter. He says, “You must try to beat Nomura out of the batting title.” He had the RBI lead sewed up and I”m about seven ahead in home runs and he”s hitting about .340 and I”m hitting about .320.

“No one had won the Triple Crown in Japan up to that time and my batting coach and other great Japanese hitters from the past didn”t want him to be the first. They wanted me, an American of all things, to try to prevent this from happening.

“The coach says Nomura always gets a late-season slump and his batting average would start coming down. I told him not to worry, I was going to win the home run title. “No,” he said. “That”s already been decided. Just concentrate on the batting title.” I asked how it could already be decided, but I didn”t think much more about it,” he recalls.

From that moment, Spencer had few chances to hit. All but two teams in the league were walking him, giving him no chance for home runs. In protest he once went to the plate holding his bat upside down, providing a photo opportunity for Japanese newspapers that published the picture widely. Still, they walked him.

But in a late-season series against the Hawks, Spencer almost caught the Japanese star. “We struck out Nomura and now he”s hitting about .320 and has 40 home runs and I have 37. I hit a home run off an American, Joe Stanka, who”s one of the few pitchers who”ll pitch to me, but we knocked him out and they walked me the next two times. Now I have 38 home runs and my confidence is really sky high. I had 11 games left and I made up my mind to catch Nomura.

“Our next games were at home against one of the two teams in the league that would pitch to me. Funny thing in Japan, I could just say, “I”m gonna hit a home run today” and most of the time I could. I told my wife at dinner, “You”d better come to the game tonight. I”m gonna hit one. I might even hit two.”

“I had a little Honda motorcycle that I”d ride to the train station where I”d park it and take the Hankyu train to the ball park. I got about 200 yards from the house when I saw this little delivery truck waiting in a side street. Then he came out, knocked me into the wall on the opposite side of the street as I tried to avoid him. I missed the last 11 games of the season with my leg broken and Nomura won the Triple Crown. I really believed I could of won the home run title, but I guess we”ll never know.”

Did Nomura or his backers arrange an “accident”?

“Who knows?” Daryl replies. “I laughed about it later.”

After five seasons as a player, Spencer returned home. “One of the smartest things I did was fly first class to Japan my first year. They continued to pay me for first class tickets, but I traveled coach and made $2,000-$2,500 a year. There were always empty seats on the flight, so my wife and two daughters had plenty of room.”

But two years later, he was lured back. “They called me because their attendance was down. I was always a great crowd pleaser and fans would come to the park to see what I would do next. Japanese players are very unemotional. When I did something, I”d tip my hat to the crowd. Once, and I still don”t know why I did this, I”d made the second out in an inning and instead of running back to the dugout just kept going to the right field bullpen and sat down and started talking to the relief pitchers. I figured after a couple of pitches the side would be retired and I”d return to my second base position. Pretty soon the umpire came out and made me go back to the bench. The fans got a lot of laughs out of that and my teammates loved it. Needless to say, my manager wasn”t very happy.”

He returned to Japan as a coach, weighing about 50 pounds more than his playing weight. But hitting countless ground balls to infielders — who often would take a hundred of them in their warm-up — soon shrank his waist and he was asked to take batting practice in spring training. After days of hitting balls out of the park in batting practice, he was asked to become a player-coach, and he played first base for two seasons.

“My contract as a coach wasn”t all that great but they wanted me to play a few games. I agreed and asked for a per-game reimbursement. I ended up playing in 50 or so games and made good money my last two years.”

Then he retired for good, returning to Wichita to work with a Coors distributor and manage its semipro teams. He had good players. “We won two state championships and played in four national tournaments, finishing third one year. We played about 60 games a year,” he remembers. The team produced some stars. Eric Show, Ron Gardenhire, Ray Fontenot, Mark Ross, Allan Ramirez and Mark Thurmond all played for Spencer and became big leaguers.

Spencer”s younger daughter, Kari Sue, was a teen-ager during his Coors years and his scorekeeper. At 13 “she just fell in love with Ronnie Gardenhire,” he recounts. His other daughter is Karen.

He also dabbled in the restaurant business, worked for a friend as a bartender for two years, ironic because he doesn”t drink. But mostly he has retained a deep interest in baseball specifically and sports in general. In a conversation, he can quickly recite statistics, plays and situations from a dozen sporting events. The meticulously kept scrapbooks documenting his career easily cover a dining room table when spread for a visitor. He is fond of the places where he played, although the Dodgers occupy a special place as the best organization. “They still send Christmas cards to me,” he says.

He also believes the 21st century game is not as strong as it has been. “There were only 400 of us, playing on 16 teams. Competition was unreal. Every major league team had 15-20 farm clubs. That meant if you were a shortstop, there were 20 other shortstops fighting for one major league position. I played in the minors four years. That was about average. Several players spent six-seven years in the minor leagues before getting a chance at a big league job and for a minimum of $5,000 a year.

“Still, all the best athletes were playing baseball. Professional football and baseball weren”t nearly as strong then as now. The expansion teams . . .where will they get the players?”

How was Spencer seen by those who watched him closely? After he hit a ninth-inning home run to give the Giants an 8-7 win over St. Louis in 1958, San Francisco News writer Bucky Walter noted: “It shouldn”t have required yesterday”s game-winning Merriwell home run with which Daryl Spencer stunned the St. Louis Cardinals, 8-7, to alert San Francisco fans to the fact the Giants” shortstop is as much a key player as Willie Mays or Manager Bill Rigney”s crop of gilt-edged rookies.

“But that”s how it”s been for the Quiet Man from Wichita, Kans., who is as near as the next tick of the clock to being the most under rated performer in the National League.

“The big payoff these days is flamboyance. But it”s guys like Spencer, steady as Gibraltar, who are the guts of a ball club. Ask Rigney. “He can play,” Rig said quietly in the hubbub of the Giants” locker room. “Daryl has strength. We lean on him.””

Postscript

Spencer died on January 2, 2017, at the age of 88.

Sources

Unless otherwise stated, information is based on interviews with Daryl Spencer in December 2005 and January 2006.

Bob Broeg, Baseball”s Barnum.

Brent Kelley, “Daryl Spencer — power-hitting SS,” Sports Collector”s Digest, November 22, 1991.

Jack Ellison, “In Bat Show at Lang It”s Spencer 10, Yanks 3,” St. Petersburg Times, March 24, 1960.

Bob Stevens, “Mays, 5-for-5, Spencer Rip L.A.,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 14, 1958.

Bucky Walter, “Meet Giants” “Daryl Merriwell”, San Francisco News, April 23, 1958

Full Name

Daryl Dean Spencer

Born

July 13, 1928 at Wichita, KS (USA)

Died

January 2, 2017 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.