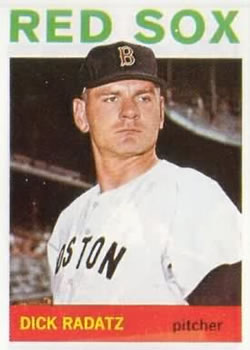

Dick Radatz

The Monster. It wasn’t a nickname Dick Radatz liked but the minute it was out there, it stuck. For three seasons (1962-1964), he was one of the most dominant relief pitchers in the game, a supernova.1 He may have been overused, perhaps burning out after facing more than 500 batters for each of four seasons in a row.

The Monster. It wasn’t a nickname Dick Radatz liked but the minute it was out there, it stuck. For three seasons (1962-1964), he was one of the most dominant relief pitchers in the game, a supernova.1 He may have been overused, perhaps burning out after facing more than 500 batters for each of four seasons in a row.

Radatz holds the major-league record of most strikeouts in a season by a relief pitcher. In 1963 he struck out 162 batters, which remains the third most all time. The next year he broke his own record by striking out 181 batters. That record still stands as of 2021.2 The National League record of 157 was set in 2004 by Brad Lidge of the Astros.3

Most starting pitchers would be thrilled to win 15 games in a season, but Dick Radatz did so as a reliever — twice. Radatz was 15-6 in 1963, and 16-9 in 1964, extraordinary wins totals for a relief pitcher. Both years his number of wins placed him in the top 10, ranking up with starting pitchers of the year.

He’s also said to have been the only major-league ballplayer to be at home watching the game on TV — but then entering the game and earning the win. The reference, though, may be to a spring training game against the Cubs on March 26, 1964 in Scottsdale. Manager Johnny Pesky didn’t want to use him that day, so Radatz was seated with his family in the grandstand. The game went into extra innings, and Pesky beckoned to Radatz who dressed, entered the game, and threw the final three innings — but he bore the loss, 10-8, in the 15th inning.4

Radatz, who had a gift of exaggeration, told the story another way, noting a time when he had worked seven days in a row at Fenway Park and manager Johnny Pesky told him to take the next day off. He was sitting at home in Milton, he said, and watched the first three innings on TV. “The kids were going nuts running around the house, so I went to the ballpark.” Pesky asked him how he felt and put him into the game during the eighth, and he won it in the 13th.5

As his nickname suggests (he was also called “Moose”), Radatz was large in stature, a right-hander listed at 6-feet-6 and 230 pounds. Those who met him and maybe have shaken his hand might swear he was several inches taller and much most robust. Yet despite his size and strength, Radatz may have been overused. Even in an era where relievers commonly went more than one inning — and were expected to do so — the Monster’s workload was unusually heavy. He faced more than 500 batters in each of his first four seasons, averaging two innings per appearance. He was already becoming less effective in 1965. Yet Radatz himself claimed never to have had arm problems; he said his difficulties were mechanical.6 Whichever it was — burned out or fouled up — by 1966 he was a spent force. By 1969 his career was over.

Radatz was of German/Irish ancestry, born as Richard Raymond Radatz in Detroit, Michigan on April 2, 1937. His father Norman Radatz worked in a Detroit automobile factory as an automotive engineer, a body design draftsman. Norman and Virginia (Osterman) Radatz came from Michigan and New York, respectively. Dick was their first-born.

As it happens, Dick grew up admiring Tigers pitcher Hal Newhouser. Speaking of his father Norman, Dick recalled, “My father lived in the same neighborhood as Hal and helped raise him.”7

That neighborhood was where Dick grew up — in the Detroit suburb of Berkley, Michigan (in the area originally known as Royal Oak), going through the public schools and graduating from Berkley High School. He played football, baseball, and basketball in high school and went on to Michigan State University. Disputing reports that he was granted an athletic scholarship, he said that was not the case, and in fact he had to take a special entrance exam because his high school grades were so marginal. He said he aced the exam, though, with one of the highest marks ever recorded.8

Radatz needed time to develop as a pitcher in college. One account came from his roommate there, Ron Perranoski, who became a star reliever for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Minnesota Twins.9 Radatz took a big step forward in the summer of 1957, when both he and Perranoski played for the Watertown Lake Sox of the Basin League. This high-quality regional circuit, based in South Dakota, existed from 1953 to 1973. Well over 100 of its players (mostly college men, but some pros) went on to the majors. Radatz posted a 10-1 record in 1957, and when he returned to the Lake Sox in 1958, he led the Basin League in strikeouts with 107.10

In September 1958, while starting his senior year, Dick married Sharon Lee Cooper. The two had dated since they were both 15, and both attended Michigan State. Sharon and Dick later had three children: Leigh, Dick Jr., and Kristine.

MSU baseball coach Johnny Kobs had steered him away from basketball, telling him there was a chance he could make it to the majors if he focused on baseball. “Actually, I didn’t have much hope,” Kobs confessed later. “When Dick first reported, he was a big, cocky kid, who knew all the answers. You couldn’t tell him anything. But as soon as he realized how much he had to learn, he did an about-face. Before he graduated, he had become the easiest, most coachable kid I ever handled.”11

He was 10-1 with a 1.12 ERA in his senior year at Michigan State but didn’t attract the lasting attention of that many scouts. Some felt he was too hotheaded. The Red Sox were able to sign him for a modest amount. Area scout Maurice DeLoof and Chuck Koney share credit for the signing.12

Radatz started 47 minor-league games, and threw 18 complete games, but he never once started in a big-league game. His first year in the minors was in 1959 with the Raleigh Capitals in the Class-B Carolina League. He appeared in 13 games, starting in 12, and was 4-6 (with a 3.04 ERA) in 77 innings. The team finished first in the standings, with Bill Spanswick (15-4) leading the league in both ERA and winning percentage. Carl Yastrzemski’s .377 batting average led the league.

Radatz’s 1960 split was split, about two-thirds of the season with Raleigh (9-4, 3.79 in 107 innings) and the Triple-A Minneapolis Millers (3-0, 3.50 in 54 innings.) Of the combined 30 games in which he pitched, 21 were as starter but the other nine were in relief. In 1961, Radatz pitched for manager Johnny Pesky’s Seattle Rainiers (also Triple-A ball, in the Pacific Coast League) and he worked exclusively in relief. Pesky had apparently been told by the Red Sox to look for a relief pitcher, since that was a need of the big-league club. Radatz pitched five innings in an exhibition game and struck out 11, and Pesky told him he wanted him to work out of the pen. “A reliefer?” Radatz reportedly asked. “What the hell do I want to be a reliefer for?” “Because the Red Sox need one, and that’s the quickest way to make the ballclub,” Pesky answered. “That’s different,” Radatz replied.13 He appeared in 54 games, throwing 71 innings. Despite a very strong 2.28 ERA, he had a losing 5-6 record.

Radatz reported to Red Sox spring training in 1962, and made the team. Told he would receive the $7,500 minimum salary of the day, he reportedly replied, “I don’t care if you give me five bucks, as long as you take me back to Boston.”14

Making his major-league debut on Opening Day, Radatz struck out 13 of the first 27 batters he faced. In fact, over the course of his first dozen appearances, he did not allow even one earned run. By the time he allowed his first earned run, it was on a harmless sacrifice fly in the May 15 game against the Yankees. By pitching a full three innings of relief, he earned his seventh save in that game. From May 13 through June 14 — a full month — he threw 34 consecutive scoreless innings. On June 9, that included six scoreless innings of relief, followed only two days later by 8 2/3 innings of scoreless relief.

At the time, the record for strikeouts in a nine-inning game was 18. In four games against the Washington Senators — July 29, August 3, and both halves of a doubleheader on August 5 — Radatz pitched a total of eight innings and struck out 17.

Radatz quickly came to enjoy the role of a reliever. “I wouldn’t want to go back to being a starter,” he said. “I would not trade my job for any other in baseball. I like the challenge of it.”15

By year’s end, he had compiled a remarkable rookie record: he led the league in pitching appearances (62), games finished (53), and saves (24). He had a record of 9-6, with a 2.24 earned run average, best of the Red Sox. He’d worked 124 2/3 innings. Radatz came in tied for third in Rookie of the Year voting. The Sporting News bestowed their “Fireman Award” on him.16

Though he did not lead the league in any of the above categories in 1963, he had a significantly better season. Without starting a single game, he won 15. Only starter Bill Monbouquette won more for the Red Sox, who finished in seventh place. The Monster’s record was 15-6, with a 1.97 ERA. He had worked in 132 1/3 innings in 66 games, averaging just over two innings per relief appearance. Manager Johnny Pesky worked him hard, on six occasions having him pitch four or more innings of relief in a game. In addition to his 15 wins, he saved 23 games — for a total of 38 wins or saves, precisely 50% of the wins the 76-85 Red Sox had that year.

He also pitched in the 1963 All-Star Game in Cleveland. A single, a stolen base, and another single brought in one run, but he struck out five of the eight batters he faced, and the run was not a consequential one.

He developed a strong sense of confidence along the way. Bill Monbouquette was due a $5,000 performance bonus if he won 20 games in 1963 — a lot of money for a ballplayer in those days. On September 15 at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, the 19-9 Monbouquette only lasted 5 1/3 innings, forced to leave the game with two men on base, with one out and a two-run lead. Monbo asked him if he remembered the promise he’d made to help him get to 20. Radatz replied, “Bill, I’m not only going to win you this game because it’s No. 20, but also as a wedding present. So go sit down and stop worrying.”17 He worked the final 3 2/3 innings of the game and the score never changed: Red Sox 6, Athletics 4.

He might have had even a better year in 1963, but he tailed off the last two months. He was 12-1 (1.38) at the end of July, then 3-5 the rest of the way. The cause may have been tonsillitis, and on October 11 he had his tonsils removed at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In the offseasons, Radatz had taught junior high school civics in Royal Oak, Warren, and Birmingham, Michigan.18 Over the winter of 1963, he hosted a five-night a week sports radio show on WCOP in Massachusetts.

Stu Miller won the AL “Fireman of the Year Award” in 1963. That bothered Radatz a bit. He wanted to win it again. “I get a special kick out of saving a victory for another pitcher,” he said. “I love to come into a game in the late innings with the game at stake. It’s a challenge for me.”19

He thrived on the role of a reliever. “Too many pitchers lack real guys. I don’t. I relish pressure,” he said. “I live for it.” He eschewed advice from coaches to get the batter to hit the ball into the ground for an out. He didn’t want to rely on the fielders behind him to be error-free. “Errors can’t happen, “he explained, “unless I let the man get some wood on the ball. So 97 percent of the time I’m working with just one idea –to strike out the hitter. I’m attacking him and making him feel the pressure.”20

Radatz had also come to embrace his nickname. “My family didn’t go for the nickname. But I realize no harm is intended.”21 He no doubt appreciated that it may have helped provide a degree of intimidation.

He enjoyed spinning stories about his prowess. Talking about another game we are unable to locate, given the clues in the tale, Radatz spoke of a game Earl Wilson had started. He was leading 2-1, but the Yankees had the bases loaded in the top of the ninth. The three batters due up were Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, and Elston Howard. As Wilson handed Radatz the ball to take over, Radatz purportedly told him, “Pop me a beer in the clubhouse. I’ll be right in!” And then struck out all three batters, on 10 pitches.22

Though his best career stats were against Oakland, he developed a reputation as a Yankee killer early on. Through his first three seasons, he was 5-0 with 11 saves against New York. In 1964 alone, he was 3-0 with an ERA of 1.19 and four saves. Ralph Houk, who had managed the Yankees in during Radatz’s first two seasons called him “the best relief pitcher I have ever seen.”23 Mostly he overpowered batters with his fastball. “The hitters know what is coming,” Houk said, “but they can’t do anything about it. He has a slider which helps him with lefty batters, a pretty good change-up which he uses only rarely and no curve to speak of.”24

The 1964 season was nearly an equal to 1963 in many respects. His record was 16-9 with a 2.29 ERA with a league-leading 29 saves. In finishing 67 games, he led the majors. In all, he appeared in 79 games (John Wyatt was first, with 81.)

His 16 wins as a reliever set an American League record. Roy Face, with 18 wins for Pittsburgh in 1959, held the National League record.

Radatz’s reprise in the All-Star Game was his worst performance of the season — 2 2/3 innings, and a blown save (and the loss) allowing four earned runs. In the regular season, only twice did he yield as many as three earned runs. His final pitch haunted him for a good long time. He’d seen the game get tied, 4-4, but just struck out Hank Aaron for the second out in the bottom of the ninth. There were two runners on base. Johnny Callison hit a three-run home to win the game. “On one pitch I go from MVP to donkey. That loss stuck with me a while. Usually, I could go out after a loss, have a few beers and forget it. Not that one.”25

He finished in the top 10 in league MVP voting for the second year in succession.

He did, however, win the Fireman of the Year award again. And Boston baseball writers voted him the team’s MVP.26

Over his first three years, the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle had only one hit against Radatz. It was a home run. There was a story that circulated in later years, printed in a number of publications, that Mantle had faced Radatz 63 times and struck out 47 times. Asked by this author to run the actual totals back in September 2002, Dave Smith of Retrosheet found that Mantle had 16 at-bats against Radatz and struck out 12 times.

Radatz’s star began to fade in 1965. He had perhaps kept up too blistering a pace to maintain. Before the season began, new manager Billy Herman had announced that he would not be called into a game unless the Red Sox were ahead.27 Radatz reportedly worked harder to be in shape for spring training, and the team began to use film to study and improve his delivery.28 He blew a save in three of his first five appearances, though in one the Sox came back to win. In each of those outings, he gave up three earned runs. His second win came thanks to a six-inning relief effort in Baltimore. And it only took until May 5 for Herman to use him in a game the Red Sox were losing, 5-2.

His year-end record shows him 9-11 (for a ninth-place Red Sox team under manager Billy Herman), but with a 3.91 ERA that was closing in on double as any ERA from his first three seasons. He still struck out twice as many batters as he walked, but for each of the three preceding years that ratio had been more than three times as many. He improved over the course of the ’65 season, and had spectacular outings such as the May 28 game against Kansas City when he struck out seven of the nine batters he faced. But he had gotten off to a poor start, with an ERA over 7.00 as of May 21; it was still over 5.00 as late as July 27. An anonymous A.L. batter asked rhetorically, “Look, how much blood can you get out of a turnip?…The Monster isn’t a mechanical man. You go to the well every day and some day the well is out of water.”29 Radatz had his own diagnosis: “I fooled around too much with different pitches in spring training. I was throwing too much side-armed stuff, and the lefty hitters were waiting for it. I’m going back to my over-handed delivery.”30

The highest salary Radatz received was in 1966, a reported $42,500. Perhaps with some of his typical exaggeration, he declared, “And I was the highest paid player on the Red Sox. The average salary then in the big leagues was $18,000 a year.”31 Radatz started the 1966 season with the Red Sox, but was not used as frequently. He appeared in 16 games (19 innings), and had an ERA of 4.74 with a record of 0-2. He was even being booed in Boston. On June 2, he was traded to the Cleveland Indians for Don McMahon and Lee Stange. It was a move from a last-place team to a first-place one, and Radatz said it gave him a feeling “just like Christmas Eve.” He added, “I’ve been going bad. I needed more work [at Boston] but they just couldn’t give it to me.”32

Indians manager Birdie Tebbetts said, “If Radatz is capable of doing the job he did before, we will win the pennant.” Radatz explicitly agreed. Tebbetts added, “It’s a gamble for the pennant we just couldn’t afford to pass up.” Pitching coach Early Winn was put in charge of “Operation Reclamation.”33 The gamble did not pay off. He didn’t win a game all year long, and was 0-3 (4.61) for the Indians. Tebbetts didn’t finish out the season; he “resigned” on August 19. Cleveland finished in fifth place.

Radatz expressed confidence in the spring of 1967, saying he only wanted to prove himself. He said it was his fault that he had faltered, blaming it on his decision to try to develop a sinker in spring training 1965.34 He didn’t convince new manager Joe Adcock and after three brief April appearances the Indians dealt him to the Chicago Cubs on April 25 for a player to be named later. The Indians finished eighth. After the season, they were sent outfielder Bob Raudman, who’d played in 16 big-league games and never played in another one.

Radatz pitched in the National League for the first time, but the batters weren’t fooled any more than A.L. batters had in recent times. He appeared in 20 games (1-0) but, with an ERA of 6.56, his last game with the Cubs was on July 7. A week later, he was optioned to the Cubs’ Triple-A team at Tacoma in the Pacific Coast League. He’d lost his control, working 23 1/3 innings but walking 24 batters, hitting five more, and uncorking nine wild pitches.

Radatz was angered and said he would quit, but quickly came around and reported. He didn’t pitch much for Tacoma, though, just 22 innings over 15 games, giving up 22 earned runs. He was 0-2. On July 23, he tied a league record with six bases on balls in one inning (he also threw three wild pitches).35 All in all, he walked 33 in the 22 innings, hit seven batters, and threw an even dozen wild pitches. Sent to Chicago for a medical examination in August, it was found he had a pinched nerve in his right shoulder that had left him with numbness in his fingers. Treated for three weeks, he recovered well enough to pitch in the fall instructional league in Arizona.36

The Cubs were hopeful and brought him to spring training in 1968, but when he started a “B game” in Tucson against the Indians on March 15, he couldn’t get the ball over the plate, throwing 24 successive balls.37 Nine days later, he was simply released. He worked out with the San Francisco Giants, but they weren’t convinced. the Detroit Tigers took a flyer, signing him as a free agent on April 22. He spent the entire 1968 season pitching for the Triple-A Toledo Mud Hens. He got in 110 innings of work and found himself, with 103 strikeouts and only 23 walks. He had a 2.78 ERA. But he was still considered washed up, and not a single team drafted him that winter.38

The Radatz family lived in Farmington, Michigan that winter and Dick worked selling insurance for Penn Mutual. He was hopeful of pitching for his hometown Tigers, but was prepared to pack it in if he couldn’t make the club.39 He had undergone a course of hypnosis under the care of a Detroit psychiatrist, to help him regain his control.40 He did make the club, when two other veterans relievers — Roy Face and John Wyatt — were given unconditional releases. Radatz won the April 29 game against Washington, his first big-league win in two years. He worked in 11 games over the first two months of the 1969 season, with a respectable 3.38 ERA and a 2-2 record. The Tigers sold his contract; Radatz said, “I could never really figure out why.”41

It was on June 15 that the Montreal Expos purchased his contract. He switched leagues again and over the next couple of months worked in 22 games for the Expos. He’d seemingly lost whatever he had found, and was 0-4 with a 5.71 ERA over 34 2/3 innings. On August 26, the Expos released him.

Radatz finished his major-league career with a 3.13 ERA and a 52-43 record, with 120 saves. He struck out 745 batters in 693 2/3 innings. He averaged more than 1.8 innings of work per game.

He didn’t hit for average, with as lifetime .131 average. He drove in 11 runs, though only one after the 1964 season.

Who had he considered the toughest hitter he had ever faced? “Tony Oliva. If you ask anyone who pitched in the American League in the 60s, they’ll tell you he was as tough an out as there was.”42

After leaving the game, Radatz worked at a number of jobs, including working for Welcor, a copying machine business. He sold industrial lumber at one point. He had his own weekly radio show for a while, and was a frequent guest on other sports talk radio shows, always suggesting that today’s relievers weren’t durable enough — somewhat along the lines of someone talking about they walked 40 miles to school every day, though Radatz was saying the same thing he had said during his career. There was no such thing as overwork. It was when he didn’t get used as much that he lost his edge.

He moved back to the Greater Boston area, and from around 1984 until his death at home on March 16, 2005, Dick Radatz lived in Easton, Massachusetts. Apparently former teammate Jerry Moses had found him a job at a corrugated packaging company.43 Radatz was happy to move back: “I felt I had formed a love affair with this town, that I was appreciated by the fans here.”44

In the 2003 and 2004 seasons, he worked as pitching coach for the North Shore Spirit, an independent league team based in Lynn, Massachusetts. The team was managed by former Sox infielder John Kennedy, and they were expecting Radatz to return in 2005.

Radatz’s death was accidental, falling down a flight of basement stairs and hitting his head on the carpet-covered concrete floor.

In 1997, Dick Radatz was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame.

Last revised: September 13, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Rob Wood.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Radatz’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Gabriel Schechter, “Dick Radatz: Baseball’s Supernova,” National Baseball Hall of Fame website posting dated March 9, 2005.

2 The National League record is 157 Ks, achieved by Brad Lidge of the Houston Astros in 2004. Thanks to Lyle Spatz. When Radatz struck out 181 opponents in 1964, he wasn’t all that far behind the strikeout leader, New York Yankees starter Al Downing, who had 217 in 87 more innings.

3 Thanks to Lyle Spatz of SABR’s Records Committee.

4 Radatz, Called from Stands, Loser in 15-Inning Contest,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1964: 37.

5 Rich Marazzi, “Radatz Reminds When Sox Fans Had Two Monsters,” Sports Collectors Digest, undated article in Radatz’s player file. No such game can be found in Radatz’s record.

6 Fred Stabley Jr., “Radatz Says He’ll Be Back,” Lansing State Journal, May 5, 1968: 87.

7 Ibid.

8 Al Stump, “Dick Radatz: He’s in Charge,” Sport, June 1965: 66.

9 In a 1963 Sports Illustrated feature, Perranoski described Radatz’s sophomore year with the Spartans. “In the last game of the year we were playing Iowa, and we were losing late in the game. Radatz hadn’t pitched one inning all year, but the coach yelled down to him to warm up. I saw him loosening up, and I went over to him and said, ‘Dick, this doesn’t make sense. You’ll lose a whole year of eligibility for pitching one inning. Tell the coach you have a sore arm.’” Joe Jares, “Look! It’s the Monster,” Sports Illustrated, April 19, 1965.

10 “Radatz Blanks Kernels Again,” Mitchell (South Dakota) Daily Republic, June 28, 1958: 8. “Duffy Finishes First in Basin Home Run Race,” Mitchell Daily Republic, August 26, 1958: 8. For an online history of the Basin League, by SABR member David Trombley, see http://www.usfamily.net/web/trombleyd/BasinHistory.htm.

11 Al Hirshberg, “Monster of the Red Sox,” Sport, October 1963: 36.

12 Chuck Koney is per the Hall of Fame’s Diamond Mines scouting report. DeLoof’s pursuit and signing is detailed in Al Stump, “Dick Radatz: He’s in Charge,” 67-69. Stump says there was a $5,000 bonus on signing and then $5,000 more at each stage if he reached Class A, Triple A, and the Red Sox.

13 Al Hirshberg, 96.

14 Ibid.

15 Hy Hurwitz, “Big-Boy Radatz — Red Sox Rally Wrecker,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1962: 3.

16 Hy Hurwitz, “Radatz Will Mix New Pitch with Hummer, Slider,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1963: 14.

17 Al Stump, 66.

18 Ibid.

19 Larry Claflin, “Dick, Red Sox Rescue Ace, Called ‘Best Ever’ by Houk,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1963: 3.

20 Al Stump, 67.

21 “Dick Disliked Monster Tag at First, Now He Loves It,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1964: 3.

22 Steve Guschov, “Dick Radatz, The Top Reliever the Red Sox Ever Had Pitch,” unidentified newspaper clipping in Radatz’s player file. The same story is told in a dozen other newspapers, looking at Radatz’s and Wilson’s game logs, cannot be identified.

23 Larry Claflin, “Dick, Red Sox Rescue Ace, Called ‘Best Ever’ by Houk.”

24 Ibid.

25 George Sullivan, “Remember…Dick Radatz?” Boston Globe, August 28, 1977. Radatz wasn’t necessarily about to have been named MVP, since he’d just given up the run that tied the game four batters earlier.

26 “Dual Laurels for Relief Ace Radatz,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1965: 4.

27 “Herman Won’t Call Radatz When Red Sox Are Losing,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1965: 17. There could be an exception, had he not worked for several days, to keep him fresh.

28 Larry Claflin, “Radatz Plays A Key Role in Bosox Films,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1966: 25.

29 Larry Claflin, “Hub Gloomy; Batters Blast The Monster,” The Sporting News, May 22,1965: 17.

30 Ibid.

31 Russ Conway, “The Monster Lives As Do His Memories,” unidentified newspaper clipping in Radatz’s player file.

32 Tim Moriarty, “Indians Receive Radatz,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1966: 49.

33 Russell Schneider, “Old Doc Wynn Given Job of Rejuvenating Radatz’ Tired Blood,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1966: 7, 8.

34 Russell Schneider, “Radatz Will Take Rookie’s Attitude To Indians’ Camp,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1966: 22. The suggestion to work on a sinker is one Radatz attributed to Ted Williams.

35 “Radatz Ties Record,” Plain Dealer, July 25, 1967: 34.

36 Edgar Munzel, “The Monster Travels the Comeback Trail,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1967: 33.

37 “Monster Misses the Plate With 24 Pitches in a Row,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1968: 29.

38 Larry Claflin, “How Fickle Is Time! No One Wants Radatz,” Boston Record American, December 4, 1968: 13.

39 Watson Spoelstra, “The Monster Draws Bead On Tiger Job,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1969: 31.

40 George Sullivan.

41 Jack McCarthy, “Dick Radatz,” Boston Herald, July 16, 1975.

42 Liam Fitzgerald, “’Monster’ Anything But Menacing On Radio Program,” unidentified January 19, 1995 newspaper clipping in Radatz’s player file.

43 Gordon Edes, “It Was Always A Monster Blast with Radatz,” Boston Globe, March 18, 2005.

44 Ibid.

Full Name

Richard Raymond Radatz

Born

April 2, 1937 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

March 16, 2005 at Easton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.