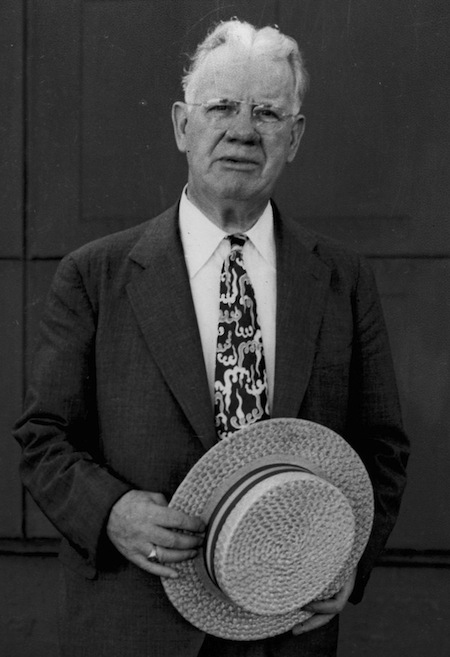

Doc Barrett

For over half a century, Charles “Doc” Barrett (1877-1954) was a trainer, first at Williams College and then at Columbia University. Although Barrett was involved with many sports, he formed a strong and distinctive connection with major-league baseball. While at Williams he did double duty as a scout for the New York Highlanders. He also trained the Highlanders from 1910 to 1914, by which time they had officially become known as the Yankees. It’s no coincidence that four of the nine Williams Ephmen who made it to the majors appeared during this period, and that three of them – Paul “Bill” Otis, George “Iron” Davis, and Tom Burr – played for New York. Barrett later scouted for the New York Giants and Philadelphia Athletics. He made at least one notable signing for Philadelphia, infielder Bill Barrett (no relation).[1]

For over half a century, Charles “Doc” Barrett (1877-1954) was a trainer, first at Williams College and then at Columbia University. Although Barrett was involved with many sports, he formed a strong and distinctive connection with major-league baseball. While at Williams he did double duty as a scout for the New York Highlanders. He also trained the Highlanders from 1910 to 1914, by which time they had officially become known as the Yankees. It’s no coincidence that four of the nine Williams Ephmen who made it to the majors appeared during this period, and that three of them – Paul “Bill” Otis, George “Iron” Davis, and Tom Burr – played for New York. Barrett later scouted for the New York Giants and Philadelphia Athletics. He made at least one notable signing for Philadelphia, infielder Bill Barrett (no relation).[1]

After serving Williams from 1897 to 1921, Barrett spent the remainder of his life with Columbia. The Big Apple’s sportswriters took to this genial, colorful, entertaining character. Upon Barrett’s death, Irving Marsh of the New York Herald-Tribune paid an especially vivid tribute. Marsh called Doc “one of the last of a fast-vanishing breed of men who inhabited college athletics in the early part of the [20th] century. They were, in addition to being trainers and conditioners, morale men, men the athletes loved to have around because, as Barrett expressed it, they were ribbers as well as rubbers.”[2]

Charles Edward Barrett was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, child of Michael and Ann. He played football and other sports as a lad.[3] In 1894, still a teenager, he embarked on his life’s work. At first he devoted his efforts mainly to bicycle racers, although he also worked with football and basketball teams. In 1897 he drew broader attention as the Worcester High School crew, which he had trained and conditioned, won the national intermediate eight-oar championship in Philadelphia.[4]

Shortly thereafter, Barrett went to Williams. There is strong reason to believe that he connected with major-league baseball through Hall of Fame pitcher Jack Chesbro. Chesbro was a native of North Adams, Massachusetts, just east of Williamstown in the far northwestern corner of the state. In January 1905 Sporting Life observed, “Chesbro takes excellent care of himself up in the winter in North Adams. He is a stickler for exercise.”[5] Not only was Barrett right next door, he too had a connection to North Adams. In fact, in 1927, Columbia’s alumni newsletter wrote that he was from there.

Sometime in the first decade of the 20th century, Barrett began scouting for the Highlanders, for whom Jack Chesbro pitched from 1903 through 1909. In August 1907 Sporting Life reported that he had signed Brown University’s ace pitcher, Raymond Tift, for New York. Tift appeared in four games in the majors over the following month. (Doc Barrett is not to be confused with Charles Francis Barrett, who began his career as one of the game’s most outstanding scouts a couple of years or so later.[6])

Sometime in the first decade of the 20th century, Barrett began scouting for the Highlanders, for whom Jack Chesbro pitched from 1903 through 1909. In August 1907 Sporting Life reported that he had signed Brown University’s ace pitcher, Raymond Tift, for New York. Tift appeared in four games in the majors over the following month. (Doc Barrett is not to be confused with Charles Francis Barrett, who began his career as one of the game’s most outstanding scouts a couple of years or so later.[6])

Another Williams player, catcher Clyde Waters, signed with the Highlanders in July 1907.[7] Although Waters never made it to the majors, he played in the minor leagues through 1914. That spring, according to Barrett, Connie Mack, owner-manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, was interested in a pitcher named Joseph Ford, the ace of the Ephs staff.[8] Mack came from East Brookfield, Massachusetts, just a few miles west of Worcester. He liked college players and might have crossed paths with Barrett years before. Three Mackmen later coached baseball at Williams while Barrett was there: pitcher Andy Coakley (1911-13), catcher Ira Thomas (hired August 1916, resigned February 1921), and pitcher Jack Coombs (succeeded Thomas, went to Princeton in September 1924).

Williams re-engaged Barrett for another five-year term in 1908. His reputation had already spread through New England; the Meriden (Connecticut) Daily Journal wrote, “His success has been marked in many athletic contests when the condition of the Williams teams have [sic] carried them to victory.[9] In March 1905 the Boston Globe wrote, “The Williams College basket-ball team has just closed a remarkably successful season and now claims the national intercollegiate championship” with a record of 20-2.[10] The 1906-07 edition of Spalding’s Official Basket Ball Guide carried a photo of Barrett and the Eph cagers.

Before long, sports fans in other regions would come to know Barrett’s name even more widely. In the summer of 1910, with the permission of the Williams Athletic Council, Highlanders owner Frank Farrell hired Barrett to work with his team. Both the Atlanta Constitution and the Pittsburgh Press carried a story describing Barrett as “one of the most expert students of muscular anatomy in the country. . . . The players and Mr. Farrell have become so impressed with the methods of Mr. Barrett that he will be kept with the team during the entire time of his vacation from his duties at Williams College. Mr. Barrett works on the same principles as the famous ‘Bonesetter’ Reese, of Youngstown, O.”[11] Reese, who was born in Wales in 1855, had learned the trade of “bonesetting” in his homeland. Welshmen used this term for treatment of muscle and tendon strains, not actually setting broken bones. Reese’s practice – and Barrett’s – resembled osteopathy.[12]

Almost straight away, Sporting Life began to carry items about how Doc had cured broken fingers, charley horses, and sore arms. In 1913 Frank Farrell said that Barrett was “in a class by himself.” Highlanders manager Frank Chance added, “Barrett has more practical knowledge of how to cure sprained ankles and wrenched arms than anybody.”[13] (The skipper, who suffered from lumbago, also benefited from special massage treatment.[14]) In addition, Barrett also oversaw nutrition, directing food shipments to the team’s spring training site in Bermuda. “Pastry, ices, and similar dishes shall be tabooed.”[15]

Indeed, that year the team wanted to have Barrett all to itself; Sporting Life reported in January that he would resign his place at Williams. An account several weeks later in the Boston Evening Transcript suggests that this was not the case, though. Doc received a silver cigarette case, inscribed, “Presented to ‘Doc’ Barrett by the students of Williams College in appreciation of his continued services and fidelity to Williams, which has helped so many teams to success.”[16]

In early 1915 Frank Farrell and his co-owner, Big Bill Devery, sold the Yankees to Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston. The Colonels brought in their own people, and that extended to Barrett’s level. In February 1915 the Yankees appointed a new trainer, Jimmy Duggan. Barrett returned to Williams, but after leaving the Yankees he did some work for the New York Giants. He had wanted to sign another Williams star, outfielder Cyprian “Cy” Toolan of North Adams, in the spring of 1914. Giants manager John McGraw remained interested the following year; he “believed he could develop [Toolan] into a valuable man for the Giants.” In July 1915, though, Toolan chose to enter business instead of taking McGraw’s trial offer.[17]

During World War I Barrett joined the US Army Air Service, taking care of flyers. He earned the rank of lieutenant. This position came about thanks to the prominent football authority Walter Camp, who helped bring a large group of noted trainers to Rockwell Field in California.[18] Doc was also trainer of the Army and Navy Aviators Baseball Club.[19] One of the friends he made there was a young flyboy named Jimmy Doolittle, who became a famous general in World War II.[20]

Other colleges wanted to lure Barrett away, but as of August 1920 he was still with Williams. The New York Times noted that he was scouting for the Philadelphia A’s in California that summer.[21] Less than a year later, though, the word came that Doc was leaving for Columbia. That November the Williams students burned him in effigy.[22]

Easily the most famous student-athlete Barrett worked on at Columbia was Lou Gehrig, who played football as well as baseball during his time there (1921-23). The Lions’ baseball coach then, and for many years to come, was Andy Coakley. Coakley, a former pitcher at Holy Cross in Worcester, had left Williams for Columbia in 1914. One wonders just what happened behind the scenes with this old boys’ network.

In addition, Barrett’s name as a comic grew. In 1927 the Columbia alumni newsletter described him and an old buddy from North Adams, one Shotsy Shanahan, as “a weekly two-man vaudeville act.” In 1943 Arthur Daley of the New York Times wrote, “For forty-six years Doc Barrett has been holding athletes together with a combination of adhesive tape and jocular remarks. He hands out both liberally, the Barrett flippancies predominating. Doc is a wag of the first water.”[23]

Irving Marsh wrote that Barrett was a fully built man with face to match, who (as he aged) had a shock of startling white hair. “He was a character out of Charles Dickens or H.G. Wells, depending on how you looked at it. The tales he told – and they weren’t all about himself either – had even his fellow trainers, and they are and were raconteurs all, open-mouthed. It was said often that he looked like the late W.C. Fields, and he reveled in that description, although when it was first applied he didn’t think it so funny.”[24]

Marsh also observed Barrett’s old-school professional methods. “Doc hated such newfangled inventions as whirlpool baths, ultraviolet machines, etc. – he’d grow violent even when they were mentioned as possible methods of relieving injuries. And he’d also grow violent about rubdowns. . . . ‘Where do you think you are, Mac – in Hollywood?’ But he did have great faith in a liniment of his own concoction, ingredients known only to him, which he shipped everywhere. He was especially proud of this snake oil and had no hesitation in telling anyone who’d listen – and you had to listen – of the vast number of great athletes he’d saved for action by application of his wonder oil.”[25]

Charles “Doc” Barrett died at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital on July 5, 1954, after a long illness. His widow, Renna Barrett, and their daughter, Ruth, survived him. Along with his applied knowledge and humor, there was another key to his enduring success in athletics: Despite his faith in his own methods, he was open-minded when it suited him. In 1925, at roughly the halfway mark in his career, Barrett told Popular Science magazine, “I’ve been at this for a whale of a long time and I don’t ever think I knew it all. I’m always watching the other fellow, ready to steal his stuff if he’s got anything better than I have.”

Thanks to Pete McHugh, assistant director of sports information/media relations, Columbia University.

Doc Barrett on What Makes a Great Athlete

More quotes from “What Sport Can You Excel In?”

By Peter Vischer, Popular Science, December 1925

“My boy, athletic champions have to be bred. They’re like horses. You can’t take any boy in the world and make a real champion out of him. He has to get something from his father and he has to get something from his mother. I know, because I’ve trained lots of boys and seen them grow up and go away and I’ve seen their sons come back to me.”

“But he must have more. He must have something here – (Barrett tapped his forehead) – “and he must have something here” – (he tapped his heart). “And neither of them can be a chestnut.”

“I am convinced that after 30 years’ study of athletes, that athletics is 95 percent mechanical. Your great baseball star, your football back who has been burning up the opposition, your hunky crew man, your slippery basketball forward, your tennis champion, your golf shark—it’s the same with all of them. They have to keep at it until their work is 95 percent mechanical.”

May 30, 2011

Photo Credits

Columbia Sports archives

Spalding’s Official Basket Ball Guide, 1906-07

Sources

www.la84foundation.org (Sporting Life online)

Notes

[1] “Columbia Looks Ahead to Hard Football Year.” New York Tribune, August 7, 1921.

[2] Marsh, Irving. “Irving Marsh’s Views of Sport.” New York Herald-Tribune, July 11, 1954. (Marsh – a mentor to Roger Kahn in The Boys of Summer author’s early newspaper days – was subbing for his better-known colleague at the Trib, Red Smith, who was on vacation.)

[3] “Charles Barrett, Columbia Trainer.” New York Times obituary, July 7, 1954.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Chesbro Chief.” Sporting Life, January 7, 1905: 5.

[6] Charles F. Barrett (1871-1939) was a longtime associate of Branch Rickey’s with the St. Louis Browns and St. Louis Cardinals. He is credited with the signing of Dizzy Dean and various other members of the Gashouse Gang, and with helping to develop Rickey’s concept of a farm system for the Cardinals.

[7] “American League Notes.” Sporting Life, July 20, 1907: 9.

[8] “After College Slab Artists.” Pittsburgh Press, April 29, 1907: 8.

[9] “Barrett Re-engaged.” Meriden (Connecticut) Daily Journal, December 23, 1907.

[10] “College Champions of America.” Boston Globe, March 25, 1905.

[11] “Yankees to Have Own Bonesetter.” Pittsburgh Press, July 13, 1910. “Bone-setter with the Yankees.” Atlanta Constitution, July 18, 1910. Several stories in later years said that Barrett began training the Highlanders/Yankees as early as 1907, but they may have been including his work as scout.

[12] Anderson, David. “Bonesetter Reese.” SABR BioProject (http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=869&pid=16948)

[13] “American League News In Nut-Shells.” Sporting Life, April 12, 1913: 7.

[14] “Yankees’ Manager Ill with Lumbago.” New York Times, March 24, 1913.

[15] “American League News In Nut-Shells.” Sporting Life, February 8, 1913: 11.

[16] “School and College.” Boston Evening Transcript, February 19, 1913.

[17] “Prefers Business Life to Baseball Career.” Binghamton Press, July 29, 1915

[18] “Looking after Aviators’ Health.” Flying, January 1919: 1147.

[19] Aerial Age Weekly, November 18, 1918: 517.

[20] Reynolds, Quentin James. The Amazing Mr. Doolittle: A Biography of General James H. Doolittle. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1953: 38-40.

[21] “Barrett Coming back.” New York Times, August 3, 1920. “Former Yank Trainer Returns to Williams.” Milwaukee Journal, August 7, 1920.

[22] “Williams Students Burn ‘Doc’ Barrett, Ex-Trainer, in Effigy.” Boston Globe, November 1, 1921.

[23] Daley, Arthur. “The Columbia Jester.” New York Times, July 18, 1943.

[24] Marsh, op. cit.

[25] Ibid.

Full Name

Charles Edward Barrett

Born

August 1, 1877 at Worcester, MA (US)

Died

July 5, 1954 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.