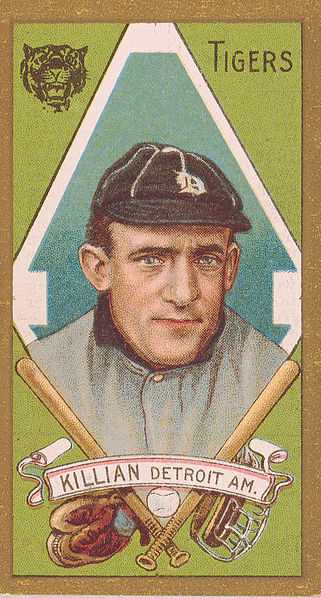

Ed Killian

Remembered in Detroit as the pitcher who won both games of a doubleheader to effectively clinch the 1909 pennant, Ed Killian was also one of the stingiest pitchers in baseball history when it came to the home run. In his entire big league career, the left-hander surrendered just nine homers, and he once went nearly four full seasons without allowing a single round-tripper. A flashy fielder and competent hitter, Killian was especially fond of the hidden ball trick, which he and teammate Charley O’Leary successfully performed on a few occasions.

Remembered in Detroit as the pitcher who won both games of a doubleheader to effectively clinch the 1909 pennant, Ed Killian was also one of the stingiest pitchers in baseball history when it came to the home run. In his entire big league career, the left-hander surrendered just nine homers, and he once went nearly four full seasons without allowing a single round-tripper. A flashy fielder and competent hitter, Killian was especially fond of the hidden ball trick, which he and teammate Charley O’Leary successfully performed on a few occasions.

Edwin Henry Killian was born in Racine, Wisconsin, on November 12, 1876, to wheelwright Andrew Killian and the former Etta Harliss, both German immigrants. As a youngster, Killian was strong and thick-chested, and became a stalwart pitcher for amateur and semipro clubs in Wisconsin and northern Illinois. In 1902, Killian signed his first professional contract with Rockford of the Three-I League. By the next season, the 26-year old southpaw was in the majors with Cleveland, winning three of eight starts in a late-season audition.

Standing a shade below six feet tall, Killian had a large jaw and big ears, and he bore a striking resemblance to Johnny Evers. Unlike Evers, however, Killian had broad shoulders, a barrel chest, and long arms. Arriving in the big leagues a little older than most other rookies, Killian had a confidence that other players new to the majors lacked. As a consequence, he often quarreled with teammates.

In February 1904, the Detroit Tigers, in need of left-handed pitching after selling Ed Siever to the St. Louis Browns the year before, acquired Killian and pitcher Jesse Stovall for outfielder Billy Lush. With the Tigers, Killian pitched regularly, earning 15 wins against 20 defeats while posting a 2.44 ERA. For the season he hurled more than 330 innings and did not allow a home run, using an effective sinkerball to induce groundballs. Never a great strikeout pitcher, Killian relied heavily on his defense to convert hit batted balls into outs. On May 11, 1904, Killian and Cy Young each hurled 14 innings of shutout ball before the Red Sox push across a run in the 15th and defeated Killian and the Tigers, 1-0.

Killian, who earned the nickname “Twilight Ed” for his tendency to pitch extra-inning games into the early darkness, enjoyed a fine season in 1905. That year he copped 23 victories, including a league-leading eight shutouts.

The 1906 campaign was frustrating for Killian, as he saw his win total cut by more than half. After losing to Jack Chesbro and the Highlanders on August 2, 1906, 11-1, at Detroit’s Bennett Park, Killian was furious at the lack of run support he was receiving. A week later he arrived at the park drunk, tore apart the clubhouse, and abandoned the team. Manager Bill Armour slapped Killian with a $200 fine and ordered the surly pitcher to remain in Detroit when the team embarked on their road trip on August 14. Unrepentant, Killian did not start again until September 19, a game in which, ironically, his teammates plated nine runs.

The outburst was typical of Killian’s reaction to adversity. When things were going well, Killian was a valuable member of the team, but when things went sour, Killian was often at the center of a storm. For example, when young Ty Cobb played his first full season with Detroit in 1906, Killian joined other veterans in hazing the sensitive and high-strung rookie. It was Killian and his good friend, left fielder Matty McIntyre, who locked Cobb out of the shower during spring training in Augusta, infuriating the young Georgian and setting the stage for a season filled with in-fighting. Describing the Tigers’ 1906 season, historian Marc Okkonen wrote that the team was “beset by injuries, dissension, and a visible absence of spirit… something had to give for 1907.”

That something was McIntyre, who was benched, lost his job, and then suffered a season-ending injury. With the contentious McIntyre out of the lineup, and with Cobb winning his first batting title, Detroit captured its first pennant in 1907. Killian returned to his winning ways, earning 25 wins behind a 1.78 ERA. Just about the only thing to go wrong for Killian, who also hit .320 for the season, came on August 7, when Philadelphia’s Socks Seybold hit a home run to beat the lefty. It was the first homer allowed by Killian since September 18, 1903, 1,001 innings earlier.

In the first of a series of post-season disappointments, manager Hughie Jennings chose to use the sore-armed Killian out of the bullpen in the 1907 Fall Classic. In Game Three against the Cubs in Chicago’s West Side Park, Killian relieved Siever (since reacquired by Detroit) with the Tigers trailing, 4-0. He pitched four innings of one-run ball and did not get a decision. The Cubs defeated the Tigers in five games (the first game ended in a tie). After the Series, with a loser’s share of $1,892 now in his pocket, Killian married Lottie McAzee, a flower girl at Detroit’s Hotel Brunswick.

In 1908 the Tigers battled Chicago and Cleveland for the AL flag down to the very last day of the season. Entering the season-ending three-game series in Chicago against the White Sox, Detroit held a 1½ game lead over the Naps and a 2½ game margin over the Sox. Killian started the first game, as more than 22,000 fans swarmed into South Side Park to see the contest. Uncharacteristically wild, Killian allowed three runs in the first without surrendering a hit, but settled down to mow down the Sox. Unfortunately, as had happened before in his career, Killian received little offensive support. Chicago’s Doc White stymied the Tigers, and despite allowing just one hit, Killian lost the game, 3-1. Nonetheless, Detroit won the final game of the series to earn its second straight flag. Killian started Game One of the 1908 World Series but was roughed up by the Cubs, surrendering four runs in less than three innings. It was his last World Series appearance as the Tigers were once again beaten by the Cubs in five games.

The 1909 season was bittersweet for Killian, who didn’t join the rotation until May due to an unidentified arm injury. The ailment limited Killian to 19 starts for the season, but when he did pitch he was very effective, posting a 1.71 ERA and three shutouts to go along with 11 victories. In September, perhaps because he was well rested due to the injury, Detroit manager Hughie Jennings relied heavily on Killian’s left arm as the Tigers once again made a push for the pennant. After “Twilight Ed” lost yet another hard-luck game (to Walter Johnson, 2-0), the Tigers held a 2½ game lead on Philadelphia. With less than a week left in the season, Jennings started Killian in the first game of a doubleheader against Boston. Killian took a no-hitter into the eighth inning before allowing a single, eventually winning the game 5-0. Twenty minutes after that game ended, Jennings ran Killian out to the mound again to pitch the second game. The lefty again shackled Boston, winning the game, 8-3 ,and effectively securing the pennant for the Tigers.

In a strange twist, Jennings abandoned Killian in the World Series, passing over his late-season hero in the rotation. Roundly criticized by pundits after the Series loss to the Pirates, Jennings had opted to start Ed Summers despite the fact that he had just overcome a bout with dysentery. “His next and greatest mistake,” the Reach Guide wrote the following spring, “was to take another chance with Summers in the fifth game, with Killian and [Ed] Willett ready and eager for the fray.”

But Killian sat on the bench and watched Detroit lose its third straight World Series. In 1910, Killian was the odd man out in the Tiger rotation and didn’t earn his first start until a month into the season. He was inconsistent at first, and then ineffective, losing his last three decisions before being sold to Toronto of the Eastern League on August 1. He had started nine games and won four, with a 3.04 ERA.

Set adrift from major league baseball, Killian went 2-6 in 10 games with Toronto in 1910 and spent the first part of the 1911 campaign there before moving on to Nashville of the Southern Association. In 1912 he began the season with the International League’s Buffalo Bisons but quickly drew his release, and pitched the rest of that summer and the next for a semipro club in Detroit.

After his playing career, Killian settled in Detroit, where he lived with his wife. Revered for his career as a Tiger, Ed took advantage of the free drinks and meals that adoring fans sent his way and worked odd jobs. Killian was hired as a mechanic by the Ford Motor Company in the early 1920s, and stayed there until he fell ill from cancer in early 1928. He died at age 51 on July 18, 1928, his wife earning a generous pension from Tigers owner Frank Navin, who called Killian the “finest left-hander ever to wear a Detroit uniform.” Killian was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Detroit.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Edwin Henry Killian

Born

November 12, 1876 at Racine, WI (USA)

Died

July 18, 1928 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.