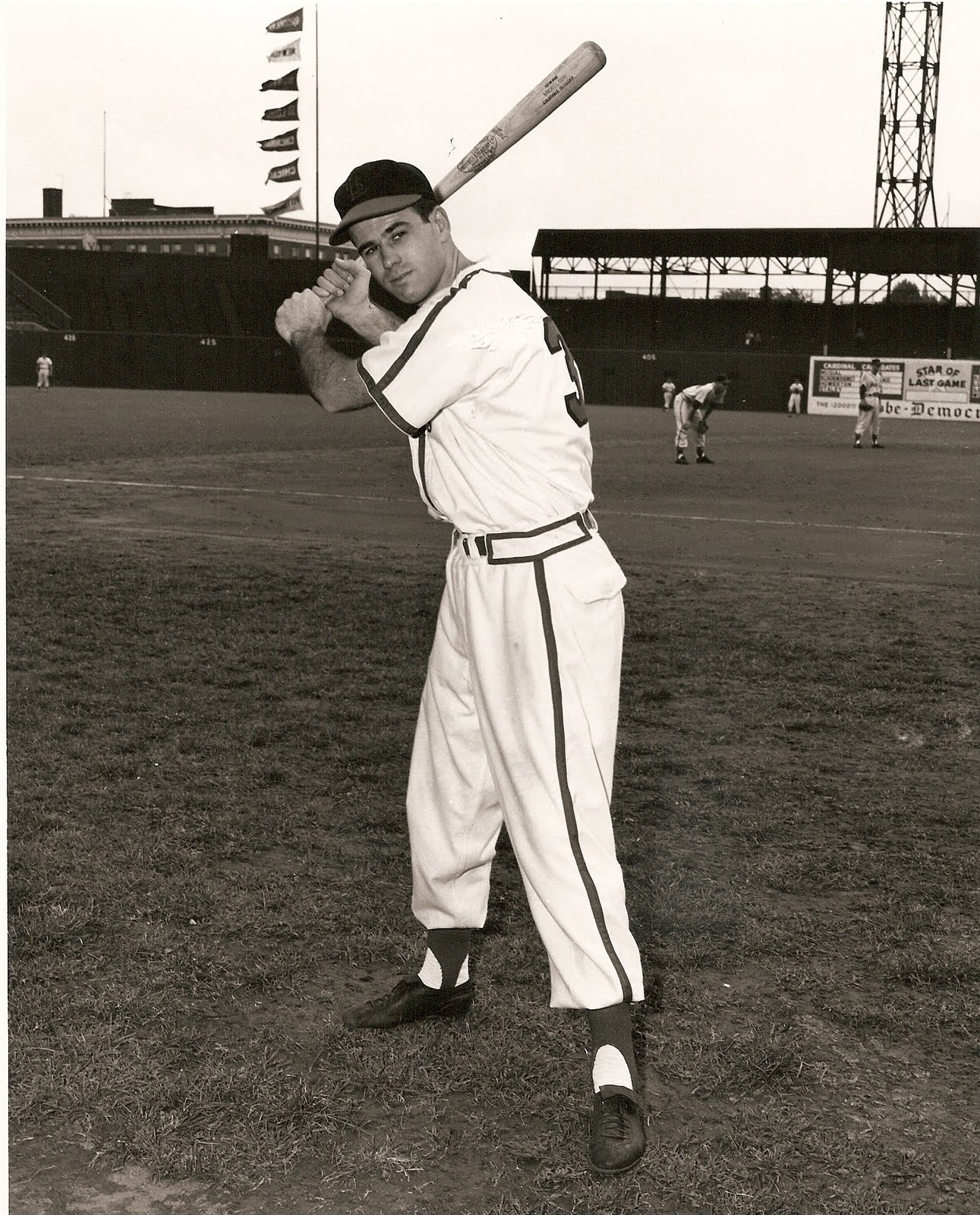

Ed Mickelson

Ed Mickelson, like so many of the 19,000-plus former major-leaguers, had a very short major-league career consisting of three cups of joe with three different organizations. But Mickelson had a very successful and memorable 11-year career in professional baseball, and has had a long and fruitful life outside of the game.

Ed Mickelson, like so many of the 19,000-plus former major-leaguers, had a very short major-league career consisting of three cups of joe with three different organizations. But Mickelson had a very successful and memorable 11-year career in professional baseball, and has had a long and fruitful life outside of the game.

Edward Allen Mickelson was born on September 9, 1926 in a hospital in Ottawa, Illinois, a city located at the confluence of the Illinois and Fox Rivers, about 80 miles southwest of Chicago.1 Mickelson’s dad, Edward, worked for the Rock Island Railroad loading freight cars. His mother Mary Inez (Cerutti) sold women’s clothes.2 The family lived down the road in Marseilles, Illinois until Mickelson turned 9. Their home absorbed thousands of blows as the youngster passed his summertime leisure hours playing catch with the wall. The young Cubs fan and his friends also cleared and maintained a ball field for their group games.3

In 1935, the elder Mickelson took a job selling insurance and the family changed from village living to urbanites by moving to Chicago. Mickelson continued his love of playing ball on the rebound. The target now became steps under Chicago’s elevated train. And instead of a ball field that he and the neighbors maintained, he played in a vacant lot on the city’s South Side. He saw his first major-league game in 1936, a Sunday doubleheader at Comiskey Park when the Yankees were in town. Mickelson doesn’t remember the score but still remembers the thrill of seeing Gehrig, Dickey, Rolfe, Appling, Simmons, and Lyons in person.4

But the family’s time in Chicago was relatively short. In 1937 they relocated to the St. Louis area in April. Mickelson’s father went back to the Rock Island Railroad, as a salesman. It was in St. Louis that Mickelson’s serious sports education took place. He played countless games of cork ball and Indian ball and also participated in the University City Playground Softball League. He usually played shortstop, as most of the best athletes do. In the eighth grade, Mickelson started playing basketball competitively, under the mentorship of junior high coach Howard Mundt. Mundt brought the youngster to St. Louis University and Washington University basketball games. Basketball became his main sport because University City High didn’t field a baseball team. When he was a senior, the high school added baseball. The football coach was also on the lookout for good athletes and recruited Mickelson. So as a senior he played all three sports. He was accomplished enough in baseball to catch the eye of Cardinals’ scout Jack Ryan during a game. But one short season of high school baseball games wasn’t enough to earn him a professional baseball contract.5

Mickelson had won publicity after catching multiple touchdown passes in a high school game, so the University of Tennessee offered him a football scholarship for the 1944 season. But before classes started, he got homesick and switched to the University of Missouri. He started as a freshman on both the football and basketball varsity teams. He modestly says he was able to do this because so many young men were in the service, but he was clearly a very good athlete, winning honorable mention on the All Big Six team. His time at Missouri was short because he enlisted in the Army Air Corps in the fall of 1944 and left for basic training in February 1945. He spent 18 months in service, the large majority of the time playing basketball and baseball for the base teams at Scott Base in Illinois.6

After Mickelson left the service in 1946, he attended Oklahoma A&M. He wanted to play basketball for the legendary Hank Iba but Iba had no basketball scholarships left. Yet he finagled a baseball scholarship for Mickelson. Mickelson started the basketball season on the bench and didn’t play in the first 16 games of the season. He did begin playing and earned more minutes as the season progressed. He was able to stay on the court as long as he focused on defense and rebounding. Mr. Iba did not want his freshman shooting the ball. The team ended the season 24-8 and Mickelson is rightly proud of his effort in the last game of the season against the eventual national runner-up, the Oklahoma Sooners. He played the bulk of the game, shutting down Oklahoma’s All-American Gerald Tucker, holding him to one free throw.7

Mickelson was proud of his basketball career. He was a 6’3” center playing hard defense against taller post players. He would front the taller players and try to deny them the ball, at the time an unusual defensive technique.8 His baseball efforts were much less successful. He hit prodigious blows in batting practice, but only managed one hit in 23 at-bats for the A&M baseball team. After the season, Mickelson received a Cardinal tryout thanks to a recommendation by traveling secretary Leo Ward. He clouted several long balls during the batting practice tryout, including a blow that scattered beer bottles stacked up in the outfield concourse. The impressed Cardinals sent him a contract for $2000. Mickelson had to decide between returning to A&M or playing professional baseball. He tried to call Mr. Iba, but he couldn’t reach the coach. So, after advice from his dad that “You should do what you want to do most,” he signed the baseball contract. The Cardinals sent him to Decatur, Illinois, one of their Class B teams in the Three I League. Mickelson had played only about 30 baseball games in uniform (15 in high school and 15 in college), so he had to learn to hit on the job. But he did a pretty good job, hitting .251 in 207 at-bats in his initial partial season in professional baseball.9

After Mickelson’s debut season, he married his high school sweetheart, Jo Ann Menzel, on November 8, 1947. He also began a pattern of attending college in the fall semester, then playing baseball during the spring and summer. He attended classes at Washington University in St. Louis, studying Physical Education. He didn’t attend the spring semester because he would have to leave for spring training before the semester ended. Jo Ann worked as a secretary to help supplement the meager baseball income and GI Bill stipend he received.10

For the 1948 season, Mickelson was assigned to the Class C Pocatello (Idaho) Cardinals. With a full spring training, he hit very well all year, ending with a .372 batting average, a .550 slugging average, and 143 RBIs. His bat earned him a place in the league All-Star game. He got the first hit of the game, which contributed to his team’s 10-3 win. Pocatello qualified for the playoffs but Mickelson was able to play only in the first round. He had to get back to St. Louis for the start of the college fall semester.11

Mickelson held his 35-ounce, 35-inch bat high and his back elbow tight against his body. That gave him a short line-drive stroke, which he used to hit to all fields. He would also recite a little prayer in the on-deck circle before his at bats. He wasn’t deeply religious, but he did carry his Bible throughout his career. He stated that he always felt a bit more comfortable when he was connected to a higher power.12

Mickelson’s season earned him a promotion to the Columbus (Georgia), Cardinals of the Sally League (Class A) for 1949. Early in the season, he shared time at first and wasn’t hitting well — his average was around .200. He was a slow starter and hit his best when he was playing regularly. By June, the Cardinals assigned the other first baseman to their Salisbury, Maryland team and opened up the job for him. After that point, he hit well (over .300 for the remaining three months). By the end of the season he had raised his average to .259 in that pitcher-friendly ballpark.

The Cardinals sent Mickelson to Class B Lynchburg in 1950. He was upset and disappointed at the step backwards. But, he turned that disappointment into motivation, batting .393 and slugging .607 in 16 games. They transferred him to another Class B team in Montgomery, Alabama. He continued to rake, getting 60 hits in his first 122 at-bats and ending the season batting .417 and slugging .737.

The combined .413 average with 24 homers earned Mickelson his first trip to the major leagues. He debuted for St. Louis at the Polo Grounds on September 18, 1950. His first at-bat was a pinch-hitting appearance against the Giants’ Larry Jansen with the bases loaded. It wasn’t a fairy tale moment — he struck out looking. Three days later he got his first start while filling in for Stan Musial, who wasn’t feeling well that day since Warren Spahn was starting. Mickelson collected his first major-league hit, a single off of the Hall of Fame lefthander.13 It was an incredible season and the Cardinals brass took note.

Mickelson attended college on the GI Bill. Some changes before the 1951 season required him to attend both the fall and spring semesters in order to continue receiving funding. He discussed this with the Cardinals, proposing to show up in time for spring training if they would pay the remainder of his education costs ($2500). They refused to pay, so Mickelson didn’t report until after the spring semester ended.14 He valued that education and knew it was important to his future. By this time all the Cardinals’ minor-league teams were filled with first basemen. So the Redbirds loaned him to the New Orleans Pelicans, a Pittsburgh affiliate. It was not a good year. Because Mickelson missed spring training, he started slowly. And then, adding injury to insult, he seriously hurt his ankle running in sloppy conditions from first to second. X-rays showed no fracture but revealed torn tendons. So the doctors put him in a hip to ankle cast for six weeks. And when he got back, there wasn’t much season left for him to try to get back into playing shape.15 It was Mickelson’s worst season in professional baseball, a lost year in his bid to make a major-league roster.

But the Cardinals hadn’t given up on him. Mickelson finished his BA degree in the fall of 1951 and was ready to report on time in 1952. The Cardinals invited him to their major-league camp, eventually assigning him to AA Houston. But management must have had some change in plans, because after having him drive to Houston to play in three games, they reassigned him to AAA Columbus — finally, a quick promotion. When he got to Columbus, the manager, Johnny Keane, told him not to unpack. He had to drive on to AAA Rochester. Initially Mickelson played regularly in Rochester, but Steve Bilko, another Cardinal first-base prospect, began taking at-bats from him in the second half of the season. General manager Bing Devine met with Mickelson to tell him he was going to send him down to Houston. In an emotional moment, a crying Mickelson clenched his fists and refused to be demoted. This clearly rattled Devine, who agreed to keep him in Rochester.16 Then, with three weeks left in the season, Mickelson was sent back to Columbus to play out the year. He was very hurt by this move but didn’t fight it.17 He had spent the season with an excellent club which went on to win the league playoffs and the Little World Series. But he missed those playoffs by being moved to Columbus. His results in that season of turmoil included a .276 batting average with two home runs in 251 at-bats.

Mickelson met with Bill Walsingham, a Cardinals vice president, near the end of the 1952 season. The organization had an abundance of first basemen and the moves from team to team added to Mickelson’s frustration. The meeting was initially civil, but his emotions took over — he demanded to be moved to a different organization. The Cardinals listened and placed him on waivers. The St. Louis Browns claimed him on the advice of manager Marty Marion, who was on the Cardinals in 1950 when Mickelson made his major-league debut.18

The Browns held spring training in 1953 in Glendale, Southern California. It was perfect weather, and Mickelson enjoyed both his time off the field with his wife and on the field getting ready for the season. But while running in the outfield near the end of spring training, his foot began to hurt. X-rays revealed a stress fracture which sidelined him for six weeks. After much treatment from Browns trainer Bob Bauman, Michelson played for AA San Antonio in the Texas League. His triple slash line for the season was a very respectable .296/.376/.428, which earned him his second major-league call-up. He appeared in seven games for the Browns, including the last game of the season. In that game, Mickelson drove in the only run the Browns scored in a 2-1 loss. Three days after the season, the Browns were sold and moved to Baltimore. So Mickelson became the answer to a trivia question: “Who drove in the last run the St. Louis Browns ever scored?” 19 He also fulfilled one of his childhood dreams, playing a game in Yankee Stadium.20

In 1954 Mickelson started spring training with Baltimore. He was playing well but the Orioles sought a different solution at first base. Late in the spring they purchased Eddie Waitkus and sold Mickelson to the independent AA Shreveport Sports in the Texas League. This was the first season in which his contract wasn’t owned by a major-league organization, but he didn’t let it affect his play. In a full season, untouched by injury or turmoil, Mickelson hit .335 and drove in 139 runs. He also played in his third All-Star game, contributing three hits in the South team’s victory. He received a watch for playing in that game which he still treasures to this day.21

The Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League finished last in 1954. That entitled them to the first pick in the 1955 minor-league draft, and they selected Mickelson among 8500 eligible players.22 So began his tenure on the West Coast. Mickelson enjoyed two full seasons in Portland, finally making a little better salary, flying between cities instead of traveling by bus or train, and basking in the cooler summer weather. Against the best competition outside the major leagues, he hit .308/.363/.457 and drove in 188 runs over two full seasons. Mickelson was justifiably proud of his fielding, which he worked very hard to improve over his career. In 1955 he set a pair of PCL fielding records for a first baseman, recording 704 chances without an error and a .996 fielding percentage for the season. Also in 1955, he was a part of Portland’s first integrated team.23

After the 1956 season, Mickelson decided to play winter ball in Venezuela. Earning $1000 a month and the promise of a warm winter were plenty of incentive. That was his first (and last) time playing in Latin America. He played for the Valencia Industriales, winning the second half of the split season but losing in the playoffs. Jo Ann joined him for the experience. He survived some scary plane, cab, and bus rides, and the fanatics who would sometimes take justice into their own hands when a bad play was made. But, overall the experience was enjoyable and he stuck around for the full winter league season.24

In 1957, the veteran Mickelson was back with Portland again. Then his favorite team from childhood, the Chicago Cubs, called. They asked him to come to Chicago, with manager Bob Scheffing promising him starts against lefthanded pitching. This likely would be his last chance at the majors, so he decided to go. He spent six weeks in Chicago and started at first in two games, while appearing as a pinch-hitter four times. He was not in the starting lineup for multiple games with lefty starters. On May 15, the roster cutdown day, the Cubs sent him back to Portland, ending his last major-league stint. This final rejection deeply affected him. He was playing well for Portland and was selected to play in the PCL All-Star Game, but wasn’t enjoying it anymore and he knew something was wrong. On July 28, 1957, Mickelson packed up his equipment and drove back to St. Louis. That was the end of his professional career. He was also diagnosed with depression and anxiety after getting back to St. Louis.25

After his retirement from baseball, Mickelson went back to school, finishing his masters degree from Washington University in Physical Education in 1957. He was a teacher, coach, and counselor for his alma mater, University City High, from 1958-1970. He then served the Parkway Central School District from 1970-1993. He coached baseball, basketball, and football, including future major-leaguer Ken Holtzman and two future NFL players. His University City baseball team finished second in the state in 1962 and his Parkway Central football team finished second in the state in 1992.

With professional help, Mickelson overcame his depression; he and Jo Ann adopted two kids, Eric (1962) and Julie (1964). He has six grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Jo Ann passed away on November 27, 1999. Ed married Mary Steffen on February 9, 2001 and remains with her today.

After Mickelson retired from teaching, he continued to coach kids at the Jewish Community Center in Chesterfield, Missouri, where he still lives today. He loved coaching and counseling and really cared about the many kids that he helped over the years.26 Mickelson also wrote his autobiography, Out of the Park — Memoir of a Minor League Baseball All-Star. According to the Baseball Players’ Association, he is one of only four major-leaguers to have written a book about their career without the help of a ghostwriter.27

Mickelson exemplified organized baseball in the Fifties, being among the thousands of minor-leaguers all trying for a job with one of only 16 major-league teams. He played with and against many former and future major leaguers, including Bobo Newsom, Carl Erskine, Willie ‘Puddin’ Head’ Jones, Dick Sisler, Gene Mauch, Vern Stephens, and many others. He went where he was told, made very little money, and gave it his best, appearing in four minor-league All-Star games at various levels. And, unlike most of those minor-leaguers, he earned three short stints in the major leagues.

Mickelson receives $1,279 annually from the major league player pension. He was not eligible for any pension payment at all until April 2011, when a change was made that included the old pre-pension players in the program. He is appreciative of the money but wishes baseball would have helped sooner. And of course he wouldn’t complain if they raise the amount he receives.28

Mickelson looks back on his life fondly, especially the relationships he formed with various teammates and with the kids he counseled and coached over those eventful years. He relates six lifetime highlights when asked.

- The support he received from family and friends,

- Being the first pick of the 1954 minor-league draft,

- Setting the fielding percentage record for first basemen in the PCL,

- Playing with Satchel Paige, Stan Musial, and Ernie Banks,

- Having his book published, including the last chapter discussing his depression, and

- Being honored by Washington University in the St. Louis Browns display in the Olin Library.

He has also enjoyed sharing his memories with people in the St. Louis Browns fan club and while attending meetings of the Bob Broeg Chapter of SABR.29

Last revised: August 24, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Brian Flaspohler, interview with Ed Mickelson, March 30, 2018.

2 Ibid.

3 Ed Mickelson, Out of the Park, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007: 5.

4 Ibid., 7.

5 Ibid., 10.

6 Flaspohler, March 30 interview with Mickelson.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Mickelson, Out of the Park: 22.

10 Flaspohler, March 30 interview with Mickelson.

11 Mickelson, Out of the Park: 42-43.

12 Flaspohler, March 30 interview with Mickelson.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Mickelson, Out of the Park, 78-79.

16 Brian Flaspohler, interview with Ed Mickelson, May 20, 2018.

17 Mickelson, Out of the Park: 103-104.

18 Ibid.,105.

19 Ibid., 122.

20 Flaspohler, March 30 interview with Mickelson.

21 Ibid.

22 Mickelson, Out of the Park: 135.

23 Ibid., 59.

24 Ibid., 195.

25 Ibid., 206.

26 Flaspohler, March 30 interview with Mickelson.

27 Brian Flaspohler, interview with Mark Littell, November 2017. The other four (and possible others) are subject to additional research.

28 Brian Flaspohler, interview with Ed Mickelson, July 27, 2018.

29 Flaspohler, May 20 interview with Mickelson.

Full Name

Edward Allen Mickelson

Born

September 9, 1926 at Ottawa, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.