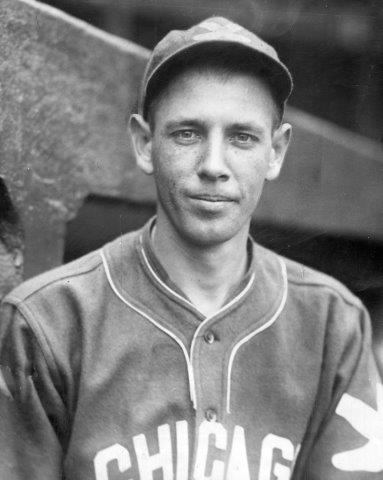

Ted Lyons

Ted Lyons is remembered as the “Sunday pitcher” who started only once a week for much of his career. He made the most of his workdays, finishing nearly three out of four starts with more complete games than any other contemporary pitcher. Forget won-lost record, Lyons said: “A good pitcher is a pitcher who has the ability to go the distance in a lot of games, and to hold opposing clubs to low scores and infrequent hits.”1

Ted Lyons is remembered as the “Sunday pitcher” who started only once a week for much of his career. He made the most of his workdays, finishing nearly three out of four starts with more complete games than any other contemporary pitcher. Forget won-lost record, Lyons said: “A good pitcher is a pitcher who has the ability to go the distance in a lot of games, and to hold opposing clubs to low scores and infrequent hits.”1

Lyons never played in the minors; he spent his entire career with the Chicago White Sox, who posted a winning record only five times in the 21 years that he wore their uniform. Lyons was one of the most popular players in the team’s history, friendly to all and a clubhouse cutup except on the days he pitched, when he never shaved and his teammates knew to stay out of his way.

Theodore Amar Lyons was born on December 28, 1900, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and grew up on a farm in the heart of Cajun country. He started playing baseball with a rolled-up sock and a broomstick. At 16 he weighed only 135 pounds and had to choke halfway up on his Joe Jackson-model bat. He soon grew bigger. When the Philadelphia Athletics spent spring training in Lake Charles, manager Connie Mack promised to pay the teenager’s way through college if he would sign with the A’s. “For all he knew,” Lyons remarked later, “he might have been paying for an eight-year course—he didn’t know whether I was dumb or smart.”2 Lyons turned down the offer.

At Baylor University in Waco, Texas, he earned four varsity letters each in baseball and basketball, plus two in track. The baseball coach told him to forget about pitching and play the outfield. Lyons didn’t take that advice, either. He became the team’s pitching star. “I studied one term of law and then came to realize I had a little better fastball and curve than I did a vocabulary,” he said.3 (Lyons once said he went to Baylor on a trombone scholarship but lost his scholarship when someone stomped on his trombone during a fight. That sounds like one of his trademark tall tales.)

In the spring of 1923, the White Sox trained in Seguin, Texas. When several of the big leaguers dropped by Baylor’s ball field, Lyons pitched to catcher Ray Schalk. Schalk recommended the young right-hander to manager Kid Gleason. The Sox signed him for a $1,000 bonus as soon as he graduated in June. He spent $428 of his windfall on a new Ford Model-T.

Lyons joined the White Sox in St. Louis. On July 2 he sat in the dugout watching the first major-league game he had ever seen—until Chicago fell behind and acting manager Eddie Collins sent him in to pitch the final inning. “When I walked out on the mound, I felt enclosed,” he recalled. “You see, I’d been used to playing on pastures, where when somebody hit a ball you had to stop it from rolling. Well, this field had fences around it. And of course in those days the Browns had big crowds, because they were usually contenders, so there was a lot of noise.”4 He retired the side in order. He pitched eight more times that year with a 6.35 ERA. His only victories came on the same day, when he relieved in both games of a doubleheader.

In 1924 Lyons split his time between starting and relieving, but was not impressive: a 4.87 ERA in 216 1/3 innings. For the next six seasons, 1925-1930, he blossomed into one of the American League’s best pitchers, twice leading the league in victories while winning more than 20 games three times and losing 20 once. He accounted for 30 percent of his team’s wins and finished in the top 10 in ERA four times. But the Sox rose no higher than fifth place.

On September 19, 1925, Lyons held the Washington Senators hitless until two were out in the ninth. Even the Washington fans were rooting for him, but pinch-hitter Bobby Veach lofted a looping single over the first baseman’s head.

Less than a year later, on August 21, 1926, Lyons started against the Red Sox at Fenway Park. The leadoff hitter, Jack Tobin, walked on four pitches. When Lyons threw ball one and ball two to the next batter, manager Collins ordered a reliever to get warm. But Lyons retired that batter, then Baby Doll Jacobson lined to center. Johnny Mostil plucked the ball off his shoetops and doubled Tobin off base to end the inning. Lyons allowed only one more base runner, on an error, and finished his no-hitter by taking a toss from first baseman Earl Sheely and stepping on the bag for the final out.

He became friends with the erudite Princeton alumnus Moe Berg, a utility infielder for the Sox. Lyons said, “He makes up for all the bores in the world.”5 On August 6, 1927, Lyons was scheduled to face the Yankees’ Murderers Row lineup. All three White Sox catchers were hurt, and they had just signed a replacement who arrived fat and out of shape. Lyons asked for Berg, who had served as the emergency catcher in only one major-league game. The Sox beat New York, 6-3, as Berg made a spectacular play to tag a runner at the plate.

The educated battery teamed up several more times. “In the years he was to catch me, I never waved off a sign,” Lyons said.6 As the possibly apocryphal story goes, whenever Lyons allowed a runner to reach second base, Berg would stop flashing signs and he and Lyons would speak Greek to call the pitches.7 The pair later joined Lefty O’Doul on a visit to Japan, where they coached young players and laid the foundation for baseball’s popularity in Asia.

Lyons also befriended Chuck Comiskey, the grandson of the Sox owner: “He was there when I was a kid bouncing around the ballpark. He was like a father to me. He was a very moral and high-class man.”8 Years later Comiskey recalled, “I never knew anyone who disliked him or said an unkind word about him.”9

Following the lead of his manager, Jimmy Dykes, Lyons was a raucous bench jockey and prankster. He and Red Sox outfielder Doc Cramer would try to sneak up on each other so they could smash an egg on the other man’s head. Lyons entertained teammates and fans with a never-ending fund of stories. Many of them involved his own (imagined) feats as a hitter. “One day there were two out in the ninth and I hit a pop fly so high that the fans got tired of waiting for it to come down. So they all went home and listened to it drop by turning on the radio.”10 He claimed to have played in an exhibition game at Joliet state prison until the warden ordered him to the bench because his line drives were punching huge holes in the prison wall. In real life, the switch-hitter was considered one of the best-hitting pitchers of his time, with a .233 batting average.

Fortunately for those around him, he was usually good-natured. At 5-foot-11 and 200 pounds, he was a powerful man who roughhoused like an overgrown boy, hoisting teammates and opponents off the ground. The Senators’ Buddy Lewis said, “He was probably the strongest man I knew in the big leagues. He could pick me up by the shirt and just shake my damn teeth out.”11 Lyons and Lou Gehrig liked to test their muscles by arm-wrestling. According to Chuck Comiskey, the wrestling matches stopped when Lyons noticed that he was winning too easily. Lyons told Jimmy Dykes, “You can’t see it when he’s at the plate, but something’s wrong with him.”12(It’s not clear whether this happened in 1939, when Gehrig was obviously ill, or the previous year, when the first signs of his physical decline went largely unnoticed.)

Despite his physique, Lyons was not a power pitcher. He struck out only two or three per game; his strikeout rate is the lowest of any Hall of Fame pitcher whose career started after 1920. His money pitch was a sailing fastball that he gripped along the seams and gave a twist as he released it. Today it would be called a cut fastball. The old-time pitching star Ed Walsh, a White Sox coach, encouraged him to use his slow curve as a change-up, and he became a master at changing speeds to keep batters off stride. In his early years he tried to fool hitters with a “pump handle” windup, swinging his arms above his head once, twice, or three times before delivering the ball. Above all, he knew how to put the ball where he wanted it and seldom walked a batter.

When he lost 20 games in 1929, one of them was historic. On May 24 the White Sox hammered Detroit starter George Uhle for 10 hits and 5 runs in the first five innings. The Tigers battled back against Lyons to tie the score at 5-5 after seven. It stayed that way until the 21st. Lyons pitched 13 consecutive scoreless innings, although he was often in trouble. Uhle was even better, holding the Sox scoreless for 15 rounds and giving up only seven more hits.

Uhle led off the top of the 21st with a bad-hop grounder to second base. He legged it out for his fourth hit of the day, but was gasping when he reached first and was replaced by a pinch-runner. The Tigers went on to score the go-ahead run on Charlie Gehringer ’s sacrifice fly.

Detroit reliever Lil Stoner held the lead in the bottom of the 21st to make Lyons the loser in a 21-inning complete game. He gave up 24 hits and faced 85 batters. He and Uhle are major-league baseball’s last marathon men. No pitcher since has worked 20 or more innings in a game.

During his six-year run as the Sox ace, Lyons carried a heavy workload. He led the AL in complete games and innings pitched twice, and pitched the second-most innings two other times. The load apparently caught up with him in 1931. At age 30 he came down with a sore shoulder and started only 12 games all season. The pain eventually diminished, but the injury changed his career.

“I lost the good stuff on my fastball,” Lyons said. “I had to come up with something to keep me in the league. The knuckler rescued me then.”13 He had thrown a knuckleball occasionally before his injury; after 1931 he relied on it more heavily, though he was never a pure knuckleball pitcher. He reinvented himself as a junkball artist, mixing in his slow curve and what was left of his fastball.

Lyons returned to form in 1932 with a 3.28 ERA, although he finished 10-15 for a team that lost 102 games. From 1932-1934 he pitched more than 200 innings every year, but his workload shrank each season as his ERA rose. In 1935 manager Dykes began giving him six days’ rest between starts, and he rebounded with a 15-8 record and a 3.02 ERA, his best in eight years.

Dykes designated him as the Sunday pitcher who would start one game of that day’s doubleheader. “When I was a kid my mother wouldn’t let me play ball on Sunday,” Lyons said. “Then for [several] years that’s the only day I played.”14 He thrived on the lighter schedule, usually contributing a dozen or more wins each season with a better-than-average ERA. In 1939 he lowered his ERA to 2.76, the best of his career so far, in 21 starts. He was chosen for his only All-Star team, but did not play. (The All-Star Game did not exist when Lyons was in his prime.)

The rookie Ted Williams asked his teammates about the White Sox veteran: “They’d say, ‘Well, he’s not real fast, but he’s sneaky fast,’ and ‘His curve is hittable, but he gets it in good spots,’ and ‘You’ve gotta watch his change-up,’ and ‘He’s got a knuckleball,’ and ‘The one thing you can’t do, you can’t guess with the son of a gun.’” Williams often named Lyons as the one of the toughest pitchers for him to hit: “Lyons was tough and he got tougher the more you faced him, because he’d learn about you by playing those little pitcher-batter thinking games, and he’d usually out-think you.”15 He refined his control even more and led the AL three straight times in fewest walks per nine innings.

“Sunday Teddy’s” popularity grew as he grayed. In 1940, when he led the league with four shutouts, the White Sox staged “Ted Lyons Day” and fans lavished gifts and cash on their old favorite. Newsboys who peddled papers outside Comiskey Park pooled their earnings to buy him a $7 shirt. One of the boys, Peter Prevan, said, “The papers were two cents. Ted would buy a paper and give me a quarter. He’d give the other kids dimes for ice cream.” 16

In 1942, his 20th season in the majors, the 41-year-old completed all 20 of his starts, going 14-6 with a league-best 2.10 ERA. Then he joined the Marine Corps. He was too old for the military draft, but he was single without dependents. While he made no patriotic speeches about his decision to enlist, he had seen fellow players who had families sign up to do their part for the war effort. “So, take him away, marines,” the Chicago Tribune’s Irving Vaughn wrote, “but don’t lose the return address.”17 Lyons was commissioned a second lieutenant and eventually was promoted to captain.

Contemporary accounts indicate that Lyons spent a fairly comfortable war serving as a physical fitness instructor while pitching for and managing Marine Air Corps baseball teams. Late in 1944 he joined service all-star teams made up mostly of major leaguers, including Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio, that sailed to the Pacific to entertain the troops. After he faced DiMaggio in one of the games, he complained, “I left the country to get away from DiMaggio, and there he was.”18

Lyons and Williams became friends during their stay in Hawaii—but only after he reassured the young slugger that, yes, he was as good a hitter as Babe Ruth. Williams also remembered Lyons’ great strength: “When he grabbed you, you stayed grabbed.”19 Lyons saw the Cardinals’ rising star Stan Musial playing for a Navy team in Hawaii, and said Musial’s unique batting stance reminded him of “a kid looking around the corner to see if the cops are coming.” 20

When Lyons left the Marines in November 1945, he was closing in on his 45th birthday. He vowed to keep pitching until he was 50. On April 21, in the first Sunday doubleheader of the 1946 season, he spun eight shutout innings against the Browns but lost when they scored two unearned runs in the ninth. The next Sunday he went the distance again to beat the Browns, 4-3, for his 260th big-league victory. It was his last. He started three more times and lost them all, though he was never hit hard. He had completed 28 consecutive games, a streak stretching back to 1941.

Poor pitching didn’t finish Lyons’ career; his new job did. On May 23, 1946, Jimmy Dykes resigned after 12 years managing the White Sox. Lyons was the surprise choice to replace him. He later said he never wanted to manage. Inheriting a seventh-place club with a 10-20 record, he removed himself from the active roster and hired Red Faber, who had won more games than any White Sox pitcher except Lyons, as a coach. He offered a coaching job to Moe Berg, but Berg declined. Lyons shook up the lineup and tutored left-handed pitcher Eddie Lopat, who was developing into a baffling junkballer like his manager. Lopat led the team with 13 victories and a 2.73 ERA. The White Sox went 64-60 under Lyons, but could not climb out of seventh place.

The Chicago franchise, once the strongest in the American League, was a wreck. The club had been mediocre to awful since the Black Sox were banned in 1920, achieving a winning record only seven times in 26 years. Every other AL team—even the St. Louis Browns—had won a pennant during that time. The roster was heavy with 30-something journeymen; the only star, Luke Appling, was 40. The Sox edged up to sixth place in 1947, though they lost four more games than the year before. That winter they traded Lopat, their best pitcher, to the Yankees for three more journeymen. In 1948 they sank to the cellar, losing 101 times.

The sole male heir to the Comiskey legacy, 22-year-old Charles A. Comiskey II, claimed his birthright and joined the front office as vice president in 1948. Despite his respect and affection for Lyons, he did what most owners of a last-place team would have done: He fired the manager. Comiskey announced that Lyons had quit. Lyons responded, “I’ve never quit at anything.”21

Ted Lyons had been the face of the White Sox for a quarter-century. He held club records for wins, innings pitched, and complete games. (He still does.) The Sox had finished as high as third place only twice during his career; many sportswriters later said his 260 victories would have been 300-plus with a decent team. “Sure, you’d like to finish higher; it would have been more pleasant once in a while,” he said later. “And if we could have won a pennant, just one, to see what it was like, it would have been nice. But I never regretted being with Chicago all those years. It’s a wonderful town, with wonderful fans, and I can’t say enough for them.” 22

Lyons had no trouble finding work. The new manager of the Detroit Tigers, Red Rolfe, hired him as a coach. Rolfe said, “Ted, I guess you sort of hated to leave the White Sox.” Lyons replied, “Not at all. When I signed my first contract 25 years ago, they said the job might not be permanent.”23

For the first time in his professional career, Lyons put on a different uniform in the spring of 1949. Since Rolfe had never managed in the minors or majors, he may have relied on Lyons’ knowledge of other American League teams. Lyons stayed with Detroit for five years. Frank House, a bonus-baby catcher, remembered that “he was always the one who would buy the rookie pitchers a glove and a pair of shoes.” House admired Lyons’ watch, a new gadget equipped with an alarm. When House hit his first big-league home run, Lyons gave him the watch. 24

With the Tigers on the way to the first last-place finish in their history, Rolfe was fired in the middle of the 1952 season. Lyons was offered the job, but turned it down. Pitcher Fred Hutchinson was named manager. Hutch said, “When I’m pitching Ted Lyons is the manager of the club.” He gave Lyons the authority to pull him from the mound.25 Lyons was let go when the Tigers shook up their coaching staff after the 1953 season.

Once more he quickly found a new job, this time as pitching coach for the Brooklyn Dodgers under rookie manager Walter Alston. After the 1954 season Alston was allowed to choose his own pitching coach, Joe Becker, and Lyons was released.

After 31 years in baseball, Lyons was out of the game for the first time in his adult life. But baseball was not through with him. He had been steadily gaining support in Hall of Fame elections since 1951; in 1954 he was named on 67.5 percent of sportswriters’ ballots, close to the 75 percent required for election. The next year he went over the top, collecting 86.5 percent of the votes, second to Joe DiMaggio. Writers also elected another Chicago favorite, Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett, and former Dodger pitcher Dazzy Vance. The Hall’s Veterans Committee tapped Lyons’ teammate Ray Schalk and old-time slugger Home Run Baker. At the induction ceremony in Cooperstown, Lyons thanked Schalk for helping him get started and added “This is the greatest thing that can happen to a player after he ends his career.” 26

Lyons’ 3.67 lifetime ERA is the second-worst among Hall of Fame pitchers, better than Red Ruffing’s 3.80. However, his 118 adjusted ERA is equal to Tom Glavine’s and superior to that of Steve Carlton, Nolan Ryan, and 19 other Hall of Famers. (Adjusted ERA equalizes different eras and ballparks. Put another way, Lyons’ ERA was 18 percent better than the average pitcher’s.) Using a more advanced metric, wins above replacement, Lyons’ 58.8 WAR ranks 29th among Hall of Fame pitchers as of 2011, with 34 others behind him; by that measure he is a mid-level Hall of Famer. 27

The Hall of Fame election brought another benefit: The White Sox hired Lyons as a scout and minor league pitching instructor. He continued scouting for 15 years. He never married and lived with his sister Pearl on his rice farm in Vinton, Louisiana.

As he advanced into his 80s, Lyons’ eyesight was failing and he had difficulty walking. In 1983 the White Sox wanted to retire his number 16 in a ceremony at the 50th-anniversary All-Star Game in Comiskey Park. Team chairman Jerry Reinsdorf offered to send a private plane to pick him up, but Lyons wouldn’t go. Reinsdorf said, “I think he declined because he would think it would have been embarrassing for him to have someone help him walk onto the field.”28 Besides, Lyons said he didn’t want his number retired; he wanted some young player to wear it.

Lyons’ health continued to decline, and he died in a nursing home in Sulphur, Louisiana, on July 25, 1986, at age 85. The White Sox retired number 16 the following year.

An updated version of this biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 Interview with Baseball Magazine, quoted in Eugene Murdock, Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940 (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler, 1991), 229.

2 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real, reprinted in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1988), 89.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., 91.

5 Joseph A. Reaves, Taking in a Game: A History of Baseball in Asia (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 67.

6 Nicholas Dawidoff, “Scholar, Lawyer, Catcher, Spy,” Sports Illustrated, March 23, 1992, online archive.

7 Daniel Okrent and Steven Wulf, Baseball Anecdotes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 95.

8 Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1986: C3.

9 Ibid., July 26, 1986: A3.

10 Wendell Smith, “Little White Lyons,” Baseball Digest, May 1957: 20.

11 Rick Van Blair, “Opposing Pitchers Couldn’t Stop Him, But a War Did,” Baseball Digest, July 1994: 58.

12 Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1986: C3.

13 Jack Ryan, “Knuckle King Bans Knuckler,” Baseball Digest, October 1946: 6.

14 Honig, Reader, 99-100.

15 Ted Williams with John Underwood, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1969, repr. 1988), 68.

16 Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1986: C3.

17 Ibid., October 15, 1942: 29.

18 Jimmy Cannon, “No Escape,” Baseball Digest, May1954: 20.

19 Williams, My Turn At Bat, 78.

20 The Sporting News, August 20, 1947: 13.

21 Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1948: B3.

22 Honig, Reader, 88-89.

23 Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1948: A1.

24 Rob Trucks, The Catcher: Baseball Behind the Seams (Indianapolis: Emmis Books, 2005), 146.

25 Harold Sheldon, “Mid-Year Hook Gets a Workout,” Baseball Digest, September 1952: 70.

26 The Sporting News, August 3, 1955: 12.

27 WAR calculated by Sean Smith at http://www.baseballprojection.com/war/top500p.htm.

28 Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1986: A3.

Full Name

Theodore Amar Lyons

Born

December 28, 1900 at Lake Charles, LA (USA)

Died

July 25, 1986 at Sulphur, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.