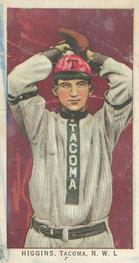

Eddie Higgins

Gifted with intellect, musical acumen, and athletic ability, Deadball Era pitcher Eddie Higgins deferred a life in dentistry for the opportunity to play professional baseball. Though he pitched in just 18 big-league games in 1909 and 1910, and he was just 22 when he made his final appearance at the top level, he enjoyed an event-filled minor-league career. Higgins also remained connected with the game well into middle age as an amateur circuit player and enthusiast, the demands of a busy dental practice notwithstanding. In time, failing health deprived him of ability to continue his profession; he spent the final decade of his life as a hospital charity ward patient.

Gifted with intellect, musical acumen, and athletic ability, Deadball Era pitcher Eddie Higgins deferred a life in dentistry for the opportunity to play professional baseball. Though he pitched in just 18 big-league games in 1909 and 1910, and he was just 22 when he made his final appearance at the top level, he enjoyed an event-filled minor-league career. Higgins also remained connected with the game well into middle age as an amateur circuit player and enthusiast, the demands of a busy dental practice notwithstanding. In time, failing health deprived him of ability to continue his profession; he spent the final decade of his life as a hospital charity ward patient.

Thomas Edward “Eddie” Higgins was born on March 18, 1888, to a devout Catholic farming family in rural Illinois.1 Eddie was the youngest of 10 children born to Daniel Higgins (1844-1936) and the former Mary Fallon (1847-1928). His father and mother were natives of New York and Ireland, respectively. They experienced tragedy, losing four children during infancy.2

The exact birthplace of Eddie Higgins — typically identified as Nevada Township — is difficult to discern. Official documents cite Blackstone,3 Streator,4 and LaSalle County.5 Regardless, his name became attached with Dwight, a community of 2,100 residents located southwest of Chicago. Throughout his career, sportswriters routinely branded him as “the peerless Dwight flinger,”6 and “the Dwight star.”7 They even labeled him as “the lad from Keeleyville,”8 because of the town’s connection with the Keeley Institute and its unorthodox alcoholism treatments.

Details of Higgins’ childhood remain elusive, but he maintained aspirations beyond his farm laboring roots. He had an affinity for music, with a voice in the tenor range and proficiency on the violin. Like his older brother Frank (1886-1966), his professional sights were fixed upon dental school. But Col. Frank L. Smith, a man with political moxie and a penchant for the dramatic, served as benefactor to one of Illinois’ premier semiprofessional teams. Smith had a knack for securing top-flight talent from the region.9 He noticed the Dwight High School hurler — who would eventually grow to 6-foot-1, 174 pounds — had a good fastball.

Higgins received his first taste of semipro action as a member of his hometown team, the F.L. Smiths, on May 19, 1907. The youngster stymied his opponents for eight nearly flawless innings. The rooters at Dwight’s West Side Park were dazzled as Higgins secured a 5-0 victory over the Joliet Giants, a team of all Black ballplayers. He allowed two hits while fanning 12 batters and contributing a 3-for-4 performance at the plate.10

Throughout 1907, Eddie tested his mettle against a mixture of town teams, semipro squads, and novelty acts. Higgins’ performance piqued the interest of the Bloomington (Illinois) Bloomers of the Class B Three-I League. Bloomers president Charles L. Miller and player-manager Bill Connors took note of Higgins’ pitching as he baffled opponents and refuted critics. Of particular interest, they were impressed by his back-to-back October pitching duels with a University of Notre Dame student who hailed from nearby Wilmington, Illinois, named George Cutshaw, later a first-rate major league second baseman.11 The two youngsters dominated opposing batsmen in splitting a pair of low-hit/high strikeout decisions.

Meanwhile, Col. Smith made arrangements with Jimmy Callahan, owner of Chicago’s semipro Logan Squares, to bring one of the major-league pennant-winning teams to Dwight. Smith intended to use the occasion to showcase his teenage hurler.12 That’s exactly what happened when a throng of baseball fanatics welcomed the Detroit Tigers, the American League champions for an October 22, 1907, barnstorming contest against the F.L. Smiths.13 More than 1,500 fans flooded West Side Park to watch Higgins battle his most formidable competition to date.14 Among the paying guests were Bloomington’s Miller and Connors.15

The Tigers thumped the locals that afternoon, 8-1.16 Higgins, who struck out five and walked three in throwing a nine-hit complete game, held his opponents scoreless until allowing an unearned run in the fourth. The barnstormers padded their lead with runs in the fifth and sixth innings,17 and sealed the Smiths’ fate with a four-run eighth. Taking note of the five Smiths errors, the Chicago Daily News reported that “Poor support back of [Higgins] cost most of the runs.”18

Higgins’ performance seemingly failed to convince Bloomers management. Whatever the case, in April 1908 Connors sent out a call for tryouts.19 Higgins responded, and the F.L. Smiths traveled to Bloomington on April 20 to challenge the Three-I locals. Higgins proved wild and his team’s defense was error-prone. As a result, the Bloomers eviscerated the visitors, 10-0, before a crowd of 600 spectators.20

Despite his unimpressive outing, Higgins was offered a contract for $115 per month by the Bloomers for the 1908 season.21 He promptly accepted but did not report until after his high school graduation in late May.22 On May 31, Higgins made his professional debut against the Peoria (Illinois) Distillers before a raucous crowd of 1,800 fans. Perhaps nerves interfered, but he was erratic opening the game, walking several men and compounding the situation by hitting a batter. After three innings, the Bloomers trailed 3-0, but manager Connors allowed Higgins to pitch through 10 innings of an eventual 11-inning, 6-5 Bloomers victory.23

Higgins quickly established rapport with Art Wilson, his batterymate, who caught three runners attempting to steal second during his first outing. However, he was not as effective when paired with Jess Orndorff. 24 Following a mid-season slump, local fans clamored for Higgins and Wilson to be paired again.25 The Bloomington Pantagraph noted the bond between the two and encouraged Bloomers faithful to “start a baseball party and nominate them for president and vice-president.”26

After a six-hit complete game win against Peoria, the Pantagraph observed that “Higgins was wild but could not be hit safely with men on bases and received fast backing.” The newspaper added that “Higgins also fielded his position in sensational style, getting seven assists.”27 A subsequent complete-game triumph prompted the Decatur (Illinois) Review to lavish praise upon the youngster’s combination of control and speed. The article claimed, “Those who paid admission got their money’s worth from his work alone.” His approach to the game — falling behind with three balls then delivering three strikes — was equated to that of collegiate pitchers of similar age.28 The Pantagraph added that “Zimri Higgins … pitched gilt-edged ball and with proper support would have shut out his opponents.”29 (It’s not known how Higgins earned the Biblical nickname.)

With Higgins’ stock rising, Pantagraph sportswriter E.E. Pierson waxed poetic about the 20-year-old’s pitching style. Pierson described a 4-0 shutout of Dubuque — in which Higgins fanned eight Dubs and allowed just three hits — as a performance “which the nightingale tells about on moonlight nights.” Pierson added: “[Higgins] had a drop that fell like an umbrella in church. His curves were sharp and terrific.”30

During the season, Higgins attracted attention from potential suitors. The Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels expressed interest as early as August.31 Later, Secretary John H. Farrell of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues announced that Higgins was drafted by the PCL’s Portland Beavers.32 The National League’s St. Louis Cardinals also expressed interest.33

Toiling for a sixth-place (64-73) Bloomers club, Higgins was among the most effective pitchers in the Three-I League. He finished his debut season with 23 wins, enough to tie for the league lead with the Clinton (Iowa) Infants’ Bill Fleet.34

Over the winter, the Cardinals purchased the services of Higgins. He then came under the oversight of player-manager Roger Bresnahan, a protégé of legendary New York Giants skipper John McGraw. Like McGraw, Bresnahan was leery about using rookies, and Higgins was denied early-season action. He finally made his major-league debut on May 14, 1909, at Washington Park against the homestanding Brooklyn Superbas. Bresnahan pulled pitcher Charlie Rhodes after he surrendered five runs on five hits in just three innings of work, bringing in the 21-year-old Higgins.35 The Superbas greeted him rudely.36 In three innings of work, Higgins allowed five runs on five hits, including an Al Burch three-run home run.

Bresnahan limited Higgins to seven relief appearances in May and June, but the rookie failed to seize the opportunities. He allowed 14 runs in 16 1/3 innings. He got no decisions, and a sign of how St. Louis used him was that the team lost every game in which he appeared. As June waned, the Cardinals shipped Higgins and Rhodes to the Southern Association’s Little Rock (Arkansas) Travelers. Management decided that Higgins required seasoning with Mickey Finn’s squad rather than wasting away with the big club.37 “It suits me a whole lot better than sitting on the bench in St. Louis where I never got a chance except to finish a game that some other fellow had lost,” Higgins said.38

To evaluate the prospect’s pitching potential, Finn pressed Higgins into service as a starter. In his Little Rock debut on July 5, he pitched a complete game against the Memphis Turtles, allowing one run on seven hits. But with no offensive support, he was tagged with the loss.

In his 11 Little Rock appearances, Higgins continued to grapple with adversity, compiling a 3–8 record. His teammates failed to generate offensive support, and his pitching fell short of expectations. The Arkansas Democrat noted, “Higgins had no bad days, or any worse than others, for every team he went against hammered him at will.”39 Higgins started all but one of his appearances and was rarely pulled from games. In apparent contrast, though, Finn said, “I didn’t have much confidence in Higgins,” following the youngster’s final Travelers appearance.40

Even so, in late August, Finn announced that Higgins would return to St. Louis following the conclusion of the Southern Association season.41 “I suppose it’s foolish to pay attention to a coward like that,” Higgins said, responding to an anonymous letter addressed to Finn accusing the hurler of indifferent play. “But still I would hate to go away feeling that Little Rock people thought that I hadn’t given them the best I had. I have the highest regard for Manager Finn, who has always treated me finely, and a ball player couldn’t ask to be with a better crowd of fellows than the Little Rock team. I’m only sorry that I couldn’t stay and finish the season with them. If I haven’t made good down here, it hasn’t been because I haven’t tried.”42

Upon reuniting with the Cardinals in early September, Bresnahan eased Higgins back in with the squad with two relief appearances. The results were mixed. Higgins retired all three Cincinnati Reds he faced in the ninth inning on September 6.43 Five days later, he surrendered four runs in four innings against the Chicago Cubs.44 With St. Louis safely out of the pennant race, Bresnahan decided to give Higgins every opportunity to impress and inserted him in the rotation. Higgins seized the chance during his first major-league start against the Philadelphia Phillies, taking a perfect game into the seventh inning. Then, Eddie Grant reached first with a bouncing single over Higgins’ head. Sherry Magee clubbed a two-run homer. That accounted for all the scoring in the Phillies’ 2-0 win.45 Higgins pitched a complete game and earned his first major-league decision with the loss.

After the rookie pitched three innings in relief against the Giants on September 23, manager Bresnahan used Higgins to close out the first game of the September 26 twin bill against the Superbas. Higgins pitched two-thirds of an inning and gained his first big-league win when the Cards scored in the bottom of the tenth. Then, in the nightcap, Higgins promptly returned as the starter. He went the distance, but St. Louis failed to score, and he suffered a hard luck 1-0 loss. For the remainder of the season, Bresnahan used Higgins as a starter, and he pitched three more route-going games. He beat the Boston Doves and the Reds, 2-1 and 8-1, respectively. His 1909 season concluded with an 8-0 loss to the Cubs.

The Cardinals went 54-98 and finished in seventh place in the eight-team National League. Completing all five of his starts and appearing in 16 games overall, Higgins registered a 3-3 record. In 66 innings pitched, he posted a 4.50 ERA, striking out 15 while issuing 17 walks.

Higgins’ 1910 season proved to be a whirlwind. As spring training closed, St. Louis Cardinals president Stanley Robison announced that the youngster would return to the major-league squad. Yet Higgins’ engagement was tenuous. His first appearance of 1910 came on April 24 against the Reds, when he allowed two runs in 2 1/3 innings. On May 14, Higgins was sold to the Western League’s Denver Grizzlies. But after a single no-decision start, Denver returned him to the Cardinals. Shortly thereafter, Higgins was sold back to the Bloomington Bloomers for $500.46 Though back in a familiar circuit, his second go-around with the Bloomers was pedestrian. Appearing in 16 games, he compiled an 8-9 record during June and July.

Nonetheless, in late July, the Cardinals reacquired Higgins.47 On July 31, he pitched his final major-league game, entering in the second inning of a game against the Cubs. He pitched the final eight frames, surrendering six runs on 11 hits. Cardinal management then shipped him to the Terre Haute (Indiana) Stags of the Class B Central League.48 Although only 22, the demotion brought Eddie Higgins’ major-league career to a close. In parts of two seasons, he had appeared in 18 games, going 3-4 with a 4.48 ERA in 76 1/3 innings pitched.

Despite earning the win in a complete-game shutout against the Zanesville (Ohio) Potters on August 6,49 Higgins managed only two wins against nine losses with his new squad. Reminiscent of some previous stops, he allowed too many runs and received insufficient offensive support. After splitting his 1910 season with four different franchises, the peripatetic Higgins found a new home with the Northwestern League’s Tacoma (Washington) Tigers. Club president George Shreeder acquired Higgins, infielder Pete “Hap” Morse, and outfielder Ody Abbott for $2,500. “My pitching staff is strong,” Shreeder said, “but the addition of Higgins will strengthen it a lot.”50

Perhaps the promise of stability in Class B baseball allowed the 23-year-old Higgins to recapture glimpses of his best form. At times he pitched brilliantly but fell short. On April 30, he took a 2-1 lead over the Vancouver Beavers into the eighth before allowing three runs to lose, 4-2.51 On May 9, he beat the Seattle Giants, 1-0, limiting his opponents to four hits.52

With Tacoma in pursuit of the league flag, Higgins got in hot water with Shreeder. During the Tigers’ 18-9 loss to the Giants on June 14, Higgins allowed all 18 runs on 24 hits. Higgins’ 9-5 loss to the Beavers on July 6 was the breaking point. On July 9, Higgins was released.53 But his time away from the team was brief — he was pitching again for the Tigers on July 13.54

Weeks later, Higgins was masterful as he pitched a 1-0 shutout against the Vancouver Beavers. With six strikeouts over nine innings, he allowed only a single to Beavers catcher Carl Lewis in the sixth inning.

Tacoma finished in fifth place at 81-84. Higgins’ performance was about on par with his club’s. He posted a 13-14 record in 29 games. Following the 1911 season, he pondered his baseball prospects and began retirement deliberations, by then an annual happening. Away from the field, Higgins was enrolled at the Chicago College of Dental Surgery as a member of the Class of 1912.55 After completing his studies early, he notified Tacoma management of his desire to walk away from baseball to open a dental practice. But when Tigers training camp commenced in March, Higgins was there.56

As he had in St. Louis, Higgins found Tacoma’s management less tolerant during his second season. Never able to harness his potential from 1908, he proved wildly inconsistent. He dazzled in a 2-1 win over Seattle but was “belted from soda to hock” by Spokane.57 In time, Tacoma manager Mike Lynch granted Higgins his unconditional release, citing his “alleged indifferent playing” and being distracted by “matters not pertaining to baseball.”58After his release from Tacoma, Higgins returned to Dwight and rejoined the semipro ranks until another franchise called.59

In late May, he returned to the Three-I League with the Peoria Distillers.60 No longer exclusively a pitcher, he occasionally played right field and first base. During his Distillers debut, he showed a glimpse of his earlier days. He pitched a 12-inning complete game against former semipro rival “Big Joe” Vyskocil but lost to the Quincy (Illinois) Gems, 2-1.61 Higgins remained on Peoria’s roster for the rest of the season, appearing in 61 games but only 21 as a pitcher, finishing with a 6-9 record and 156 innings pitched.62

Following the Distillers’ season, Col. Smith summoned Higgins to Dwight for an October 24 barnstorming game against the Chicago Cubs. With a crowd of 1,000 on hand, Higgins started and was hammered for five runs in the top of the first inning. While he struck out six batters, the Cubs won, 9-3.63

With the 1912 season complete, Dr. Higgins began transitioning to his post-playing career. He settled near his childhood home and opened a dental practice in Streator, Illinois. He also volunteered his time with the Knights of Columbus as the local chapter’s financial secretary, and brought his musical talents to church.64

In 1912, Higgins’ new hometown joined the Class D Illinois-Missouri League with a new team, the Streator Speedboys. In dire need of revenue to guarantee play in 1913, team management and civic leaders turned to Dr. Higgins. who agreed to pitch exhibition games and host a clinic to generate funds.65 Even though he was already committed to playing for the semipro Streator Reds and the Knights of Columbus squad in the new 12-team City League,66 Dr. Higgins was convinced to join the I-M League team — renamed the Streator Boosters. However, he would pitch only in local games.67 Higgins pitched three complete games and finished with a 1-2 record for the 30-37 Boosters.

Having pitched only 27 innings in 1913, Dr. Higgins increased his workload with the Boosters in 1914, exceeding 130 innings. He pitched in 16 games, completed 13, and finished with a 10-5 record. “His arm is better this year than ever,” the local newspaper noted. “He is confident he can surprise all with this work.” Despite his growing dental clientele, Dr. Higgins mentioned that “the ‘bee’ is buzzing around so much of late,” and that he continued to receive offers from major-league teams.68 According to the Streator Times, Higgins said, “he may harken the call and don a uniform regularly.”69

In early 1915, Bloomington’s Pantagraph reported that Roger Bresnahan, by then player-manager of the Cubs, wanted Higgins to join the squad during spring training.70 Rumors also swirled about offers from the Distillers or signing with the American Association’s Indianapolis Indians.71

In 1915, the I-M League folded, and the Boosters joined the Class D Bi-State League. Rather than follow the Boosters, Dr. Higgins opted for a homecoming with Dwight’s F.L. Smiths to remain in shape and wait for another professional contract. On June 7, he pitched a complete game and nearly beat the Federal League’s Pittsburgh Rebels in an exhibition game, losing a rain-drenched 11-inning affair, 8-6.72

Desiring a return to the pro ranks, Higgins wired Manager Howard Wakefield of the Three-I League’s Rockford Wakes and requested a workout.73 Local sportswriter Frank Landers said, “if he is the same old Zimri of old, he is a corker.”74 Indeed, by the end of July, Dr. Higgins was in Rockford’s rotation. Wakefield was quick to praise the former Cardinals pitcher, noting that he “has shown a nice bag of tricks.” The manager added, “The boys are enthusiastic over his work.”75

Higgins displayed confidence and cunning which served to inspire his teammates.76 Yet despite maintaining his youthful appearance, he failed to recapture much of his previous best.77 On August 1, he held the Moline (Illinois) Plow Boys to one run on five hits.78 Two weeks later, though, Higgins was hammered by the Freeport (Illinois) Commons, yielding 12 hits in five innings.79

On September 2, Chicago Cubs owner Charles Webb Murphy was in Rockford to scout the Quincy (Illinois) Speed Boys and Wakes doubleheader.80 Dr. Higgins was tapped to start the second game, but allowed five runs in the top of the first and was pulled after 4 1/3 innings. Two days thereafter, Higgins and catcher Earl Wolgamot were released.81 Despite his sharp start, Higgins pitched in only 11 games and finished with a 5-4 record.

When the 1915 season ended, Dr. Higgins decided that his journey through baseball was over for good and rededicated himself to dentistry. In August 1916 he opened an office in Rockford and shared space with former Cardinals pitching teammate Harry Sullivan,82 a Rockford native who operated his own medical practice.83

While Higgins was realizing his post-baseball career, World War I continued to escalate. After the United States joined the conflict, construction of Camp Grant, a new military cantonment, opened south of Rockford in June 1917. Drs. Higgins and Sullivan registered for the draft and offered their expertise to the local war effort. Throughout the summer, Camp Grant swelled to accommodate more than 40,000 soldiers.84 Higgins’ service in the United States Army Medical Department’s Dental Unit #1 began on March 22, 1918, at Camp Grant. Six months later, the base was ravaged by the influenza pandemic, suffering more than 1,400 deaths between September and October 1918.85

In March 1919, Dr. Higgins was honorably discharged. That same month, office partner Sullivan returned from service in France,86 but was in failing health.87 In late September 1919, Harry Sullivan died at age 31.88

With Dr. Higgins’ professional baseball days behind him, he continued to play and manage89 in city league games with the Knights of Columbus teams90 and sporadic old-timer’s games91 throughout the 1920s, 1930s, and into the 1940s. He relished opportunities to regale parents and children at speaking engagements with stories from his playing days.92

He remained a dedicated member of the Knights of Columbus and attended the group’s convention in Rockford in May 1949. While attending a function the evening of May 17 at Schrom’s Café, Dr. Higgins suffered a stroke — initially reported as a heart attack — and collapsed on the second floor.93 He was rushed to St. Anthony’s Hospital, and the next morning, was reported being in fairly good condition.94 In reality, he never recovered and remained hospitalized the rest of his life. In 1951, the Knights of Columbus’ Muldoon Council named its newly initiated members the Dr. T.E. Higgins class in his honor.95

On February 14, 1959, Dr. Thomas Edward Higgins — reduced to a pauper96 and Winnebago County indigent case97 — died in the veterans’ section of Elgin State Hospital. His sister Cora E. Higgins Gibbons (1882-1967) and her son visited the hospital that day. The former pitcher suffered a stroke while in their company and died minutes later.98 He was 70. The cause of death was officially listed as bronchopneumonia. Never married and without children, he was buried in Calvary Cemetery, just outside of Rockford.

When Macmillan published its first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia in 1969, Eddie Higgins’ name did not appear. His biographical data and brief major-league accomplishments were erroneously listed under Festus Higgins (a minor-leaguer from 1912 to 1923). “Big Mac” set the record straight in 1985 with the publication of its sixth edition. Even as late as 1999, though, The Cardinals Encyclopedia showed “Festus” instead of Eddie.

Higgins is scheduled to be inducted into Dwight High School’s Athletic Hall of Fame during the 2021-2022 academic year.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the sources consulted below, the author would like to extend a special thank-you to the Dwight Historical Society’s Kim Drechsel and Mary Flott; the McLean County Museum of History’s Bill Kemp; the Rockford Public Library’s Marie Barcelona, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Bill Francis. Like Dr. Higgins, the author is a graduate of Dwight High School and played on its baseball team.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 “D.J. Higgins Dies in Sleep: Aged 91 Years,” Dwight Star & Herald, January 17, 1936.

2 “Aged Resident Called Tuesday,” Dwight Star & Herald, April 27, 1928.

3 “Dr. T. Edward Higgins Dies in Rockford,” Dwight Star & Herald, February 20, 1959.

4 US World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917 for Thomas E. Higgins.

5 US World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942 for Thomas Edward Higgins.

6 “Higgins Pitched Winning Ball,” (Bloomington, Illinois) Pantagraph, June 11, 1908: 5.

7 “Notes of the Game,” Pantagraph, May 30, 1908: 9.

8 “Bloomington Wins in the Eleventh,” Pantagraph, June 1, 1908: 10.

9 Fred Young, “Young’s Yarns,” Pantagraph, July 23, 1975: 18.

10 “Dope for Fans,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, May 25, 1907.

11 “Young’s Yarns,” Pantagraph, October 9, 1958: 27.

12 “Detroit Tigers Coming,” Dwight Star & Herald, October 19, 1907.

13 Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight Star & Herald, August 19, 1938.

14 “Tigers Whale Dwight,” Detroit Free Press, October 23, 1907: 9.

15 “Young’s Yarns,” Pantagraph, September 17, 1961: 23.

16 “Tigers Whale Dwight,” Detroit Free Press, October 23, 1907: 9.

17 “Ee-Yah!” Dwight Star & Herald, October 26, 1907: 1.

18 “The World of Sports,” Chicago Daily News, October 23, 1907: 6.

19 “Bloomers Get Word to Report,” Pantagraph, April 2, 1908: 9.

20 “Dwight Proves Easy Picking,” Pantagraph, April 20, 1908: 10.

21 “Base Ball Notoriety,” Dwight Star & Herald, November 9: 1907.

22 “Notes of the Game,” Pantagraph, May 30, 1908: 9.

23 “Bloomington Wins in the Eleventh,” Pantagraph, June 1, 1908: 10.

24 “Mourning for Higgins,” (Decatur, Illinois) Herald and Review, July 30, 1908: 3.

25 “Three-I Peeps,” (Springfield) Illinois State Register, July 31, 1908: 3.

26 “Bloomers Get Back at the Rabbits,” Pantagraph, August 1, 1908: 5.

27 “Higgins Triumphs at Peoria,” Pantagraph, June 4, 1908: 5.

28 “Reed’s Ship Struck on Higgins’ Rock,” Herald and Review, June 11, 1908: 5.

29 “Higgins Pitched Winning Ball,” Pantagraph, June 11, 1908: 5.

30 “Bloomers Win One; Dubuque Takes Second,” Pantagraph, June 22, 1908: 5.

31 “Three-I Team on Final Spurt,” Illinois State Register, August 24, 1908: 2.

32 “Higgins to Portland,” Streator (Illinois) Free Press, October 22, 1908: 5.

33 “National League News,” Sporting Life, November 7, 1908: 3.

34 Paulson, Norman M., 1950 Three-I League Record Book: 79.

35 “Superbas Count Ten Times on Ten Hits,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 15, 1909: 11.

36 “Superbas Among the Leaders; First Place Not Out of Reach,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 15, 1909: 20.

37 “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, July 10, 1909: 2.

38 “Higgins Reports; Travelers Leave,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, July 3, 1909: 8.

39 “Baseball Notes,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Democrat, August 27, 1909: 2.

40 “Told of the Travelers,” Arkansas Gazette, August 27, 1909: 6.

41 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, August 28, 1909: 9.

42 “Told of the Travelers,” Arkansas Gazette, August 28, 1909: 4.

43 “Sure Enough,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 7, 1909: 8.

44 “Cubs Keep the Flag Pace,” Chicago Tribune, September 12, 1909: 25.

45 “Magee Loses Ball; Roger Loses Game,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 21, 1909: 11.

46 “List of Players Sold,” (Sioux Falls, South Dakota) Argus-Leader, August 2, 1910: 6.

47 “Recalls Higgins,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, July 29, 1910: 6.

48 “Radiated from the Diamond,” Rock Island Argus, August 4, 1910: 4.

49 “Terre Haute, 6; Zanesville, 0,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, August 6, 1910: 7.

50 “Tacoma Team to Get Three New Players,” Seattle Times, April 23, 1911: 24.

51 “Tigers are Still on Slide,” Tacoma (Washington) Times, May 1, 1911: 2.

52 “Fast Contest to Mike Lynch’s Men,” Spokane (Washington) Chronicle, May 10, 1911: 17.

53 “Tacoma Benefits While Spokane Loses in Disputes,” Seattle Times, July 13, 1911: 12.

54 “Tigers Win from Vancouver Bunch,” Spokane Chronicle, July 14, 1911: 26.

55 Chicago College of Dental Surgery, “Dentos 1912” (1912). Chicago College of Dental Surgery Yearbooks.

56 “Fodder for Hungry Fans,” Tacoma Times, March 23, 1912: 3.

57 “Fan Fodder,” Seattle Times, May 17, 1912: 20.

58 “Higgins Released,” Tacoma Times, May 17, 1912: 2.

59 “Dwight,” Weekly Pantagraph, May 31, 1912.

60 “Stis Buys New Catcher,” (Davenport, Iowa) Times, May 31, 1912: 9.

61 “Kerwin’s Homer Ties Up Game at Quincy,” (Davenport) Times, June 1, 1912: 15.

62 Paulson: 16.

63 “Cubs Defeat Dwight,” Weekly Pantagraph, October 25, 1912: 10.

64 “Xmas Programs at Local Churches,” (Streator) Times, December 23, 1912: 4.

65 “Stars Defeat K. of C. Yesterday,” (Streator) Times, April 27, 1914: 2.

66 “Ball Game Sunday Between League Players and Reds,” (Streator) Times, April 26, 1913: 1.

67 “League Managers All Claim Victory,” Streator (Illinois) Free Press, May 20, 1913: 2.

68 “Errors Lose for Higgins,” (Streator) Times, May 25, 1914: 3.

69 “Errors Lose for Higgins.”

70 “Ante Season Fan Fare,” Pantagraph, February 12, 1915: 5.

71 “Local News,” (Streator) Times, June 22, 1915: 8.

72 “Pittfeds Win 11-Inning Exhibition Contest,” Pittsburgh Post, June 8, 1915: 13.

73 “New Pitchers Perhaps,” Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, July 27, 1915: 5.

74 “Higgins Some Pitcher,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, August 3, 1915:7.

75 “Gossip of the Game,” Register-Gazette, August 6, 1915: 5.

76 “Crush Champs in Two Games,” Register-Gazette, August 6, 1915: 5.

77 “Some Three-I Gossip,” Register-Gazette, August 19, 1915: 5.

78 “Inability of Plow Boys to Hit Pill Results in Two Victories for Wakes,” Moline (Illinois) Dispatch, August 2, 1915: 6.

79 “Notes of the Game,” Pantagraph, August 16, 1915: 5.

80 “Diamond Gossip,” Moline Dispatch, September 3, 1915: 12.

81 “Diamond Gossip,” Moline Dispatch, September 4, 1915: 10.

82 “Breakfast Table Chat and Local Advertisements,” Morning Star, August 12, 1916: 3.

83 “Dr. H.A. Sullivan Has Offices in Trust Bldg.,” Morning Star, January 12, 1916: 8.

84 Thomas Powers, “Camp Grant and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” Nuggets of History, December 2008, Vol. 46, No. 4: 1.

85 Jeff Kolkey, “World War I Horror Revealed in 100-year-old Letters from Camp Grant in Rockford,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Star, October 20, 2018.

86 “Bright Career of Dr. H.A. Sullivan Closed by Death,” Morning Star, September 23, 1919: 12.

87 “Dr. H.A. Sullivan is Critically Ill,” Register-Gazette, September 16, 1919.

88 “Dr. Sullivan a Loser in Grim Game of Death,” Rockford (Illinois) Republic, September 22, 1919: 1.

89 “Ball Game to Feature K. of C. Family Picnic,” Register-Republic, August 18, 1948: 23.

90 “C.I.A.C vs. K. of C.,” Rockford Republic, June 14, 1924: 10.

91 “Old Timers and Kilburn Avenue Giants to Play,” Morning Star, September 24, 1932: 11.

92 “Former Sports Stars to be Club Speakers,” Morning Star, January 14, 1947: 8.

93 “Dentist Collapses from Heart Attack,” Morning Star, May 18, 1949: 8.

94 “Dentist Stricken by Heart Attack Better,” Register-Republic, May 18, 1949: 31.

95 “K.C. Exemplification Rites Slated April 29,” Register-Republic, April 20, 1951: 38.

96 “Hospital Seeks Award in Suit,” Register-Republic, October 28, 1953: 3.

97 “$6,500 Medical Release Asked,” Morning Star, July 31, 1955: 27.

98 “Stroke Fells Dr. Higgins,” Register-Republic, February 16, 1959: 4.

Full Name

Thomas Edward Higgins

Born

March 18, 1888 at Nevada, IL (USA)

Died

February 14, 1959 at Elgin, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.