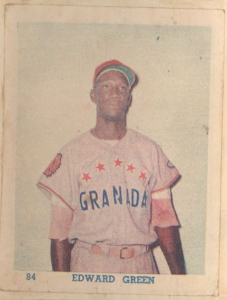

Eduardo Green

Eduardo Green (1920-1980) never played in the majors. In fact, he played only 11 games in Organized Baseball at the Class B level. Yet under different circumstances, he almost certainly could have been a big-leaguer. La Gacela Negra — The Black Gazelle — still stands as one of the greatest players in the history of Nicaragua. If that seems faint praise, it shouldn’t. This nation has a longstanding baseball tradition and a good pool of talent. Yet for various reasons, only 14 pinoleros (through the end of the 2016 season) have made it to the majors.

Eduardo Green (1920-1980) never played in the majors. In fact, he played only 11 games in Organized Baseball at the Class B level. Yet under different circumstances, he almost certainly could have been a big-leaguer. La Gacela Negra — The Black Gazelle — still stands as one of the greatest players in the history of Nicaragua. If that seems faint praise, it shouldn’t. This nation has a longstanding baseball tradition and a good pool of talent. Yet for various reasons, only 14 pinoleros (through the end of the 2016 season) have made it to the majors.

One of those men was Eduardo’s son, David Green, of whom Whitey Herzog said, “He might have been the most talented player of his generation.”1 David did not fulfill the lofty hopes that started with his father; Eduardo’s passing was one of the blows that fueled the young man’s personal troubles.

In his own right, though, Eduardo Green deserves to have his story reach a wider audience. When David broke in with the St. Louis Cardinals back in 1981, the great announcer Jack Buck would note that the elder Green had been quite a player in his day. That and a few other passing mentions in books and magazines were about as far as it went in the U.S. — one must turn to the Nicaraguan sporting press.

The statistics are hard to come by, but it is possible to pull together disparate threads of Spanish-language history. Veteran Managua sportswriter Edgard Tijerino, who befriended Eduardo in the mid-1970s, provided much insight over the years. He wrote one of the deepest available stories in 2006. The occasion was the 26th anniversary of Green’s passing, and the title in translation was “The Electrifying Gazelle.” Tijerino offered this description: “He had the soul of a ballet dancer, the vocation of a sprinter, the eyesight of an eagle, the reflexes of a panther, and the sensitivity of a hare.”2

Fortunately, two Nicaraguan broadcasters and journalists who emigrated to the U.S. have also shared much personal knowledge. They are Alberto “Tito” Rondón and René Cárdenas. These men are among the few in the States who saw El Cabo (The Corporal, as Green was also known for his army rank) actually play. Rondón, a premier historian of his nation’s baseball, reminisced over the course of late 2009 and early 2010. Cárdenas even caught Green in his prime from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s. As of 2008, he still regarded the outfielder as one of the three best position players his country ever produced.3

According to the death certificate in Nicaragua’s Civil Register, Edward Green Sinclair was born on August 30, 1920 — although other dates have circulated.4 5 He was the youngest of six children (three boys and three girls) born to David Green and Carlota Sinclair.

Green’s hometown, Bluefields, is the heart of Nicaragua’s English-influenced Atlantic coast. There runaway slaves and free blacks from the British West Indies (mainly Jamaica) joined the native Miskito population. Even today, the main language spoken in the region is an English-based Creole. Everyone began calling Edward “Eduardo” after he moved to the Spanish-speaking part of the country.

Eduardo’s mother grew up in Bluefields, but his father was an Anglican pastor who came from Jamaica. This man was an important figure in the religious life of the Miskito Coast. In 1987, author David Haslam wrote, “Especially remembered is David ‘Daddy’ Green, who in the second decade of the [20th] century established permanent programmes of worship among the Creoles and Miskitos in the Pearl Lagoon area. The work spread north, to Puerto Cabezas, and also out to Corn Island.”6 The Episcopalian had also described him vividly in 1972. “More missions were also planted by the forerunner of present day catechists, a Jamaican named David Green. ‘Daddy’ Green, full of fervor and eccentricities, wore a clerical collar much of the time.”7 Indeed, it is said that Green founded more missions in Nicaragua than any other missionary.8

Starting in the late 1880s, the Atlantic Coast population (costeños) forged a strong connection to baseball.9 Stanley Cayasso, another of Nicaragua’s enduring local baseball heroes, was from Bluefields too. His career began in 1925. In the 1960s, two other men from the town — Duncan Campbell and Willie Hooker — advanced as far as Triple A. Eventually, three other Nicaraguan major-leaguers would come from Bluefields or other spots on the Caribbean coast: Albert Williams, Marvin Benard, and Devern Hansack.

Eduardo Green first played ball in Nicaragua’s Pacific region in 1940 with the team Campos Azules (Spanish for Bluefields). They met Chinandega for the national championship but lost. At that time Eduardo was a shortstop. In 1941, he and that year’s Atlantic champions, Zelaya, came to Managua to face Bóer for the national title. After the series, Green stayed on in the nation’s capital. He joined Olímpico, which would take a new name in 1942: Cinco Estrellas.10

This team was personally associated with Nicaragua’s dictator, Anastasio Somoza García. Tito Rondón expanded. “The team was formed by high-ranking officers of the National Guard, who wanted to name it Somoza (again), but the dictator said that was too much cult of personality and said no. So the soldiers came up with Cinco Estrellas, Somoza being the only five-star general in Nicaragua. He promoted himself, basically.” The players got paid for their service in the army. Fans called them the Presidential Guard.11

On December 4, 1943, Nicaragua enjoyed its first visit from an active major leaguer, as Cardinals center fielder Terry Moore came with a team representing Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone. Eduardo played shortstop for the select national nine that day, as Stanley Cayasso was in center field, which would later become Green’s regular position.12 Albrook Field won 2-1 as Moore made a shoestring catch of Cayasso’s ninth-inning blooper and then threw out the speedy Green at the plate to save the tying run.13

Tito Rondón noted that rough baseball humor was common in Nicaragua too. “Cayasso did not smoke or drink and was very disciplined, so Green called him occasionally ‘La Cayassa,’ a woman. Sort of like Lady Baldwin [the 19th-century U.S. player who did not smoke, drink, or curse either].”

The Cinco Estrellas Tigers won nine national amateur championships in 11 years from 1944 to 1954. Green, with his speed and strong arm, was a star in left field and later in center. Tito Rondón offered more color on the ties between Cinco Estrellas and the Guardia Nacional. “If you had good seasons, you advanced in grade so that your pay increased, which is why Eduardo made corporal (cabo) and Cayasso lieutenant. The joke was that in an emergency the payment method became the real thing, and more than one player found himself in the army for real.”

Some accounts depict Cinco Estrellas as a lightning rod for opponents of the Somoza regime, who rooted for Bóer instead.14 In Tito Rondón’s opinion, in later years there was a tendency to swallow “typical Sandinista revisionist history. When the Sandinistas took over [in 1979], they did not disband the team, they just changed the name to ‘Dantos,’ and kept the players and the color of the uniforms.”

The reality is more nuanced. Rondón said, “With the heyday of the Yankees in the 1940s and ’50s coinciding with los Tigres’ own heyday, many fans identified with both [the Bronx Bombers and Cinco Estrellas] even though they hated Somoza’s guts. Conversely, many Bóer fans were ardent Somoza supporters. Somoza was so smart he founded the labor unions and also revived Bóer, Cinco Estrellas’ arch-enemy.

“The anti-Somoza daily La Prensa always tried to inflame opposition against the dictatorship from baseball fans by disparaging Cayasso and all of Cinco Estrellas. Then, when Cayasso became part of the national team for some international competition, he would become a hero again.

“One time at the stadium Somoza García was at the game and they announced that Flor de Caña’s Alberto ‘La Muñecona’ Sandino, right field, was coming to bat. A leather-lunged fan [referring to Nicaragua’s revolutionary hero of the 1920 and ’30s] shouted ‘Long live Sandino!!’ Somoza laughed as loud as anyone else. The same as when playing Bóer and Ernesto Chamorro [a surname identified with La Prensa’s editor] was announced. They were funny moments; they were invested with great political significance 30 years after Tacho [Somoza García] was shot [in 1956].

“I lived those times; it was funny finding out 35 years later that Bóer was brought back on orders from Somoza García. Bóer was the ‘People’s Team,’ of course, and the joke was:

“Who is the people’s team?

“Bóer, of course.

“You are wrong, it’s Cinco Estrellas!

“You are crazy. How so?

“It’s paid for by the people’s taxes!

“But it was the Revolution [of the 1970s] that politicized Nicaraguans; before that most people ignored the subject, though of course, in principle, everybody agreed dictatorships were bad. But at the stadium, you saw Cayasso hit, Green run, Pancho Fletes field, Conejo Hernández catch, Mundito Roberts pitch fast balls and Goyito López junk. Watching Cinco Estrellas was great spectacle always, and having Bóer beat them. . .heaven. Baseball heaven.”

Eduardo Green was not a large man, standing 5’11” and weighing about 155 to 160 pounds in his prime. He did not hit many home runs, but did get a lot of doubles and triples. Catcher Kent Taylor, a fellow costeño, said Green’s weakness at the plate was slow curves.15If one were to try to draw a parallel with a major-league player, it might be Omar Moreno or Vince Coleman; Gary Pettis and Pat Howell also come to mind. Tito Rondón said, “Cabo may not have had the consistent high averages in the Nicaraguan League that his international production suggests. He was known for his speed, base stealing and defense, and of course for being a good, but not great, hitter. Your typical pre-Bill James leadoff hitter.”

Green was also a main cog in the national amateur team, starting in 1944 and continuing into the early 1950s. It was most likely in this arena that Cuban broadcaster Manolo de la Reguera watched Eduardo and dubbed him La Gacela Negra. Nicaragua won the bronze medal in the Amateur World Series (now known as the Baseball World Cup) in 1947. Before the trip to Barranquilla, Colombia, doctors reportedly found a problem with Green’s aorta. They forbade him to make the trip. Eduardo insisted, and finally they allowed him to join the team, but on condition that he sign a waiver absolving the sporting authorities of any blame should he have a cardiovascular problem.16 Green then tied with his teammate Jorge Hernández for the tournament lead in runs scored with 14 while batting .450 (18 for 40).

The next year, playing at home in Managua, the Nicaraguans finished out of the running — but Green was the leader in RBIs with 11. The guide produced for this series shows a dramatic photo of La Gacela Negra, billed as his country’s greatest base stealer (and at just 27 years old), sliding into third against a visiting Cuban team.

Once Jackie Robinson paved the way for black players in the majors in 1947, Eduardo might conceivably have become the first Nicaraguan big-leaguer. He was about a year and eight months younger than Jackie, who reached the Brooklyn Dodgers at the rather advanced age of 28. A few years later another swift center fielder moved up from the Negro Leagues who turned out to be a good deal older. That was Sam Jethroe, 1950’s NL Rookie of the Year.

Cabo spent his prime at home, however; at some level his obligations to Cinco Estrellas, the army, and the national team may have kept him from a shot at the big time. Actually, though, Somoza did not rule the players with an iron fist. His general managers ran the team, and he was rather relaxed about restoring some men’s amateur standing after they had played a pro season or two. It is also noteworthy that the Negro Leagues were little known in Nicaragua.

In Tito Rondón’s view, “The two lost major-leaguers of the ’30s and ’40s were [José Ángel] ‘Chino’ Meléndez and Stanley Cayasso, according to legend (and, I believe, facts). You can also add Jonathan Robinson and Green to the list. Of the early players (1900s), Paco Soriano and John Deshon were almost certainly major-league caliber. I believe that at least two or three players per decade, more or less, from 1890 through 1960 had big league talent. But by concentrating on the Amateur World Series we lost the opportunity to have a pro league. That would have raised our level of play to minor-league caliber.”

Rondón continued, “I believe the defining moment in Eduardo’s baseball life came in 1950, just before the World Cup. Team Nicaragua played two practice games against Nicaraguan pros. In one of them Nicolás Bolaños [father of three men who would later play ball with Cabo’s son David in Nicaragua] was playing center field and Green was in left. Nicolás was fast, but was nothing compared to Eduardo. But he had a sure eye for the ball, the shortest routes, which shows me that Eduardo still was not all he got to be.

“Anyway, Chino Meléndez hit a monster smash, slightly left of true center, to the base of a wall that engineers had measured at exactly 500 feet. Cabo took off like a rocket and ran down the ball with his back to home plate at a spot later measured as 23 feet short of the wall. It was very much like the Willie Mays catch in the 1954 World Series, the ball went 477 feet and Green made the catch! Until the Professional League [in 1956] it was considered the greatest catch in Nicaraguan baseball history. People talked about it for decades, though now they have forgotten. But I believe Green became the center fielder that day, though not literally. Besides, Bolaños (who struck out Earl Weaver in an American Legion game in St. Louis in the late 1940s) was needed as a pitcher.”

The 1950 World Cup took place in Managua again near the end of the year, and Cabo went on another tear. He was the tourney’s leading batter, going 19 for 39 (.487) with seven doubles. Unfortunately, Nicaragua finished fifth. The manager was Andrew Espolita, who came from Tampa, Florida. A few years later Espolita would coach a boy named Tony La Russa, who became a big-league infielder and then gained fame as a manager.17

In February and March 1951, Eduardo played in the first Pan American Games in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Shortly thereafter, the Brooklyn Dodgers gave him a fleeting glance at the major leagues. Nicaraguan authors Manuel Genet and Edmundo Quintanilla thought it was 1947 or 1948, but José Daniel López — the son of a local club owner — heard one version of the story from Cabo himself in the late ’60s. In 2004, López reminisced with Tito Rondón, who had worked at his radio station.

“If I recall correctly, he [Green] said it happened in early 1951, when [Cuban baseball man] Bobby Maduro was trying to sell Brooklyn the idea that they should try Héctor Rodríguez at third base. I think just after he got back from Buenos Aires. Cabo said that when he got to Vero Beach the first thing he saw was Carl Furillo throwing a laser beam strike to home plate from deep right field. ‘I realized I had nothing to do there, so I packed up and came home.’ He was not declared professional, in those days nobody kept a close watch for that sort of thing.”

Rondón later learned what really happened from René Cárdenas. During the 1960s, Cárdenas (then an Astros play-by-play man) was broadcasting in the Winter League in Nicaragua during Houston’s off-season. He interviewed Cabo about his Dodger experience. “What René remembers is that Green was sent to train with the Montreal Royals [in Daytona Beach, Florida], and he was very disgusted with the racism he encountered. He was so mad he quit the Dodgers and came back to Nicaragua. Years later, when René talked to him, Cabo was still so mad about the experience that he used very colorful language to describe it.

“I believe Cabo was kidding with Daniel López, using material other people made up. It is possible that he visited Vero and saw Furillo, but did not wish to speak ill of the U.S. to everybody. The thing is, Green’s arm was not bad, so there was no reason to run away just from watching ‘The Reading Rifle’ unload one. Racism sounds much more plausible.”

It is tempting to think that the trailblazing scout Howie Haak (who spent several years with the Dodgers) might have found Eduardo and that he may already have been establishing his pan-American network. However, Haak — who was Branch Rickey’s man in several organizations — followed Rickey to the Pittsburgh Pirates in November 1950. Howie and one of his bird dogs, Panamanian catcher/manager Calvin Byron, would later sign various players out of Nicaragua. The most prominent were costeños, Duncan Campbell in the ’50s and Albert Williams in the ’70s. Haak also saw another of Cabo’s sons, Eduardo Jr., play a couple of years before Williams.

The 1951 World Cup in Mexico City that November was not Green’s finest hour. According to the newspaper La Noticia, he overslept and missed the game against Cuba — supposedly owing to the ill effects of having smoked a cigar, for which he provided a doctor’s certificate.18

Eduardo turned pro at last, aged 32, in late 1952. He played for Cervecería in Panama’s winter league. José Daniel López said, “Elías Osorio [a Panamanian first baseman] told me years later that Green did not hit in Panama.” The only glimpse of his numbers in The Sporting News that season shows him hitting .264 (14 for 53) as of early January, with no RBIs in the team’s first 14 games.19

Green then had a brief taste of pro ball in Cuba and the United States. He played 11 games for the Havana Cubans of the Florida International League in 1953, gaining just five hits in 27 at bats (.185). Bobby Maduro bought that club in May, but it is not known why Green departed. That winter, he played for Vanytor in the Colombian winter league, which had a working agreement with Brooklyn. According to López, “Then he was out of baseball except for pickup games until 1956, when the [Nicaraguan] Professional League started. And he came back.” Eduardo then got the chance to hit some major-league pitchers. He was still playing (and batting .247) as late as the winter of 1963-64.

Another factor affecting Green’s career, at least according to Cabo’s contemporary Alfredo Medina, was a possible problem with alcohol. In 2005, “Medinita” recalled that “Green lost himself because of this.”20 This would also be one of the reasons why his talented son David did not achieve his promise in the ’80s; heredity could well have had a bearing.

After Eduardo left baseball, he worked as a mechanic for several years. As José Daniel López observed, Cabo often remained close to the field in his leisure hours. “One afternoon in the late sixties I went to the store, the ‘27 de Mayo Pulpería.’” May 27 is the Army Day holiday in Nicaragua; in many parts of Latin America, a pulpería is a small corner store and local hangout.

“I found Eduardo Green and a friend of his having a couple of beers and talking. ‘How are you, short stuff?’ he asked me. ‘Still have a team in that league?’ He was referring to the Jugos Monarch in the Mayor ‘A’ Bolonia League.” Mayor ‘A’ is Nicaragua’s second division/municipal league system, and Bolonia is a neighborhood of Managua. The distributors of Monarch Juices, Casa Mantica, sponsored the team.

“Several years before we had lost at San Rafael del Sur (a town near Managua), because lefty Antonio Cárdenas hit and pitched a great game. My dad promptly signed him, and when he made his debut in Managua, Green was standing with some fans under a mango tree at the edge of center field. He remarked that he knew the lefthander, that he had played a few games with Cinco Estrellas and so he was a pro. He got kicked out of the league.

“After I called him a snitch we began talking, and he recalled the tryout with the Dodgers.”

Eduardo and his wife, Bertha Francisca Casaya Madrigal, had a family of ten: five girls (Carlota, Isabel, Sonia, Milena, and Geovanna) and five boys (Eduardo, Alfredo, Leonardo, David, and Enrique). The couple were married in 1960 — after all the children had been born! In addition to David, the athletic gene was present in Isabel and Carlota, who became two of the finest women’s basketball players in Nicaraguan history. Cabo had high hopes that Eduardo Jr. would follow in his footsteps as a baseball star, but while the young man looked the part, he never did much in the local amateur league. David then became the focus.

The national baseball authorities of Nicaragua enlisted Eduardo Sr. to scout and develop talent, especially in the Bluefields area. In the mid-1970s, he also served as a coach with Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) in Managua and the UCA-affiliated team that played in the Hope and Reconstruction League. (Following a split in the national amateur ranks, Nicaragua had two Division One amateur circuits from 1973 to 1977.) According to Tito Rondón, who watched Cabo throw batting practice a couple of times, he still had a great arm. Rondón also remembered Eduardo “screaming harshly in his English-accented Spanish” as he taught David, then a skinny teenage batboy, how to hit.

When David signed with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1978, Edgard Tijerino recalled hearing Eduardo say, “He’ll make it. With that vitality he has, that drive to improve I’ve instilled in him, and that raw material, he can’t fail. I only want to see him wear a big-league uniform.”21 Alas, that was not to be — Eduardo passed away on September 13, 1980. A little less than a year later, David made his debut with the Cardinals.

Eduardo’s death reflected Nicaragua’s shattered economy in the wake of the Sandinista revolution. As Carlota Green related in 2010, “He had a kidney infection, and there were complications in the hospital. He had three heart attacks, and he died after the fourth one.” In a matter-of-fact way, but tinged by sadness, she added, “This is my country.”

Shortly after Eduardo succumbed, the national baseball tournament in the Mayor ‘A’ division was named for him; the 30th edition was held in 2009. In 1982, the Nicaraguan government also created the “Orden Eduardo Green Sinclair” for excellence in sports.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Isabel, Carlota, and Alfredo Green for their help and memories (via e-mail and telephone interviews, March 2010). Thanks also to René Cárdenas, José Daniel López, and Julio César Miranda.

Sources

http://www.manfut.org/museos/sf-GreenEduardo.html

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Photo Credit

Courtesy Tito Rondon

Notes

1 Herzog, Whitey. You’re Missin’ a Great Game. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1999: 158.

2 Tijerino, Edgard. “La Gacela, electrizante.” La Prensa (Managua, Nicaragua), September 13, 2006.

3 Tijerino, Edgard. “¿Un nica en Cooperstown?” La Prensa, October 6, 2008.

4 August 30, 1919, per Genet, Manuel and Edmundo Quintanilla Mendieta, Leyendas del Béisbol Caribeño Nicaragüense. Managua, Nicaragua: 2003. Tito Rondón has cautioned that this book relies a good deal on hearsay.

5 August 23, 1923, per Arellano, Jorge Eduardo. “Nicolás y Róger Bolaños: Mundialistas y profesionales.” La Prensa, June 4, 2007.

6 Haslam, David. Faith in Struggle: The Protestant Churches in Nicaragua and Their Response. London, England: Epworth Press, 1988: 13.

7 The Episcopalian, Volume 137, 1972: 16.

8 Brooks, Ashton Jacinto. Eclesiología: Presencia Anglicana en la Región Central de América. San José, Costa Rica, Departamento Ecuménico de Investigaciones, 1990: 40.

9 Rondón, Tito. “A Short History of Nicaraguan Baseball.” Nica News, March 1998.

10 Miranda, Julio. “Cinco Estrellas, campeón de campeones.” El Nuevo Diario (Managua, Nicaragua), April 9, 2007.

11 Ibid.

12 Rondón, Tito. “Agustín Castro, CF.” La Prensa, February 7, 2002.

13 Bolsa de Noticias, (Managua, Nicaragua), January 20, 2000.

14 Suárez, Emigdio. “Nicaraguan Fans Riding Clouds Over Feats of American Players.” The Sporting News, January 15, 1958: 19. See also Brinkley-Rogers, Paul. “Baseball habla español since early days.” Miami Herald, October 24, 1997; Feldman, Jay. “Baseball in Nicaragua.” Whole Earth Review, Fall 1987.

Full Name

Edward Green Sinclair

Born

August 30, 1920 at Bluefields, South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (NI)

Died

September 13, 1980 at Managua, Managua (NI)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.