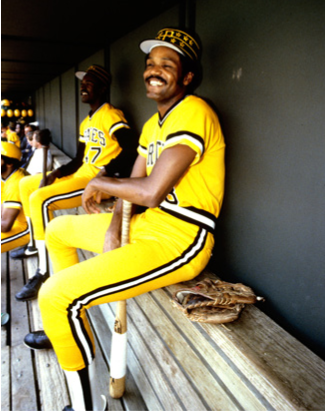

Omar Moreno

Imagine you’re playing word association with a baseball nut. Mention Commerce, Oklahoma, and the fan will respond, “Mickey Mantle!” Shout out Donora, Pennsylvania, and the fan will bellow out, “Stan Musial.” And if your next term is Puerto Armuelles, the fan is likely to shout … “Say that again?”

Imagine you’re playing word association with a baseball nut. Mention Commerce, Oklahoma, and the fan will respond, “Mickey Mantle!” Shout out Donora, Pennsylvania, and the fan will bellow out, “Stan Musial.” And if your next term is Puerto Armuelles, the fan is likely to shout … “Say that again?”

Small though it may be, Puerto Armuelles, a town in the Panamanian province of Chiriqui, is the birthplace of one of the greatest basestealers of the 1970s and 1980s, Omar Moreno.

Omar Renán (Quintero) Moreno was born on October 24, 1952, one of 10 children born to Aurelio Moreno Murillo, a foreman for the United Fruit Company, and Lidia Quintero de Moreno, a homemaker. The young Moreno had baseball in his genes — his father was a catcher in his younger days — pitching and playing the outfield. He was also a track star, building up his speed and leg strength running along the beaches near his home; his specialties were the 100-meter dash and the high jump. His speed, more than his hitting ability, attracted the attention of Pittsburgh’s head Latin American scout, Howie Haak in 1968, when Moreno was only 15. “He couldn’t hit the ball out of the infield but he surze could run,” Haak recalled.1

Pittsburgh’s Panamanian scout, Herb Raybourn, who worked under Haak, got Moreno’s parents to sign a contract on his behalf while Omar was representing his province at the Panamanian national high-school championships in the city of Chitré (Moreno went 7-for-10 in three games and led Chiriquí to its first championship).2 Moreno received quite the surprise when he returned home from the tournament.

“And so my mom says to me: ‘Did you know you’re going to the U.S. with the Pittsburgh Pirates?’” said Moreno. “I was in shock. … I said: ‘Me?’” The left-handed-batting and -throwing Moreno began his odyssey through the minor leagues with the Pirates’ affiliate in the Rookie Class Gulf Coast League in 1969. At age 16, he was two years younger than his next oldest teammate, and had to make the language and cultural adjustments common to young players from Latin American countries. He acquitted himself adequately offensively, getting into 25 of the team’s 54 games and batting .290 with no home runs, 4 RBIs, and 5 stolen bases.

Moreno, who was 6-feet-2 and weighed 180 pounds, had trouble getting beyond the lowest levels of the minors during his first few years as a professional, bouncing back and forth between the Gulf Coast League and the lower-level Class A (short season), and mostly as a part-timer at that; he didn’t play in more than 100 games in a season at one location until his fifth year in the minors , when he played in 136 games for the Salem (Virginia) Pirates of the Class A Carolina League in 1973 at age 20. He had a solid season, batting .284 with 9 home runs and 56 RBIs, all the while blazing along the basepaths with 77 steals, a league record (he also played three games with the Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies of the Triple-A International League. Those numbers got him promoted to the Thetford Mines (Quebec) Pirates of the Double-A Eastern League in 1974, where he hit .300, with 7 home runs, 39 RBIs, and 67 stolen bases.

After starting the season in Thetford Mines, Moreno was called up to the Charlies again on June 11, which was a wild day to be sure. Moreno was informed that morning of his promotion, then spent the day traveling to Charleston, where he found out that he was starting in that night’s matchup against the Pawtucket Red Sox. That game lasted 16 innings and did not finish until after midnight. If Moreno was tired after the game, he could at least take comfort in the fact that he scored the tying run as Charleston overcame a two-run deficit in the bottom of the 16th to win 10-9. After the game, Moreno and his teammates boarded a bus for the five-hour trip to Toledo, Ohio, where they started a four-game series against the Mud Hens the next night.

Moreno played in 23 games for Charleston and was batting only .220 when he returned to Thetford Mines for the remainder of what turned out to be a very good season. He was chosen to play in the postseason Eastern League All-Star Game.

Moreno finally got his first cup of coffee with the Pirates in September 1975 after a full season at Charleston, where he hit .284, smacked 9 home runs, and drove in 51 runs. His stolen-base total, 39, was down significantly from recent seasons. On September 5 he got the call into the manager’s office that all minor leaguers hope for, and was given a plane ticket to Montreal, where the Pirates were playing the Expos. He pinch-hit for Richie Hebner in the seventh inning of that night’s game, working a walk from Steve Rogers. He made his first major-league start on September 24, playing left field against the Phillies. He didn’t waste any time making his first major-league error, misplaying a bases-loaded single by Greg Luzinski in the top of the first that allowed “The Bull” to reach second. Moreno made up for the miscue in the bottom of the inning. Batting second in the order, he got his first major-league hit with a single to left off Larry Christenson, stole second, and scored on a single by Al Oliver. It was the only Pirates run in an 8-1 loss.

After his team finished 11th in the National League with 49 steals in 1975, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh said that his 1976 team was going to run more and that the young speedsters in the minors had a very good chance of making the big club in spring training.3 “For the Bucs to run more in ’76, Murtaugh said, youngsters such as Omar Moreno, Tony Armas, and Craig Reynolds would have to make the club,” wrote Dave Brown. “And they would have to see enough playing time to steal bases.”4

By the time the season started, however, Murtaugh felt that Moreno and at least one of his fellow youngsters still needed some seasoning. “We have some speed,” he said, but (Miguel Diloné and Omar Moreno) are a year away.”5

Moreno began the 1976 season in Charleston. It was evident by early May that he was working hard on all aspects of his game, and that the effort was paying off. His manager, Tim Murtaugh (Danny’s son), admired the Panamanian for his dedication and willingness to work hard to improve.

“He [Moreno] has a major league arm — it is strong and accurate — and he is an intelligent ballplayer,” Murtaugh said. “The only problem he had at the start of his career came from his failure to understand English. It took him a little while to catch on to what we were trying to tell him.

“He has made himself what he is today by hard work and, as I say, complete dedication.”6

That industriousness earned Moreno a brief call-up on June 20 when first baseman Bob Robertson went on the 15-day disabled list with torn ligaments in his ankle. Moreno appeared in six games and returned to Charleston on July 4 after Robertson’s injury healed. Moreno made those six games count; he got noticed when he played, at least by the media.

“The Pirates brass does some funny things,” wrote Charley Feeney. “Omar Moreno, a left-handed pinch-hitter with speed, was shipped to Charleston, and Bob Robertson, a right-handed hitter with no speed, was taken off the disabled list. The move did one thing. It strengthened the Charleston farm club.”7

Maybe somebody was reading Feeney’s article, because Moreno was called up again on August 10 after Pirates rookie catcher Ed Ott broke a bone in his right hand. That news came two days after Moreno was named to the International League All-Star team for his .315 batting average with 3 home runs, 36 RBIs, and 55 stolen bases. Moreno didn’t play in that All-Star game because this time the ticket was one-way. His confidence helped make sure of that. A few days after being recalled by Pittsburgh, Moreno found himself playing center field in the Astrodome replacing veteran All-Star outfielder Al Oliver. After being troubled with dizziness, Oliver was hospitalized while the Pirates were in Houston, and subsequently missed three weeks of action. After tests, it was discovered that Oliver was suffering from an inner-ear infection.

“Moreno has confidence now,” said Pirates general manager Joe Brown. “He feels he belongs, and this is important with any young player.”8

Moreno hit .270 in 48 games for the Pirates in 1976, and one of his early thrills was his first big-league home run, on a lucky Friday, August 13, a ninth–inning solo shot against Joe Niekro of the Astros in Houston that added the final run in an 8-5 Pirates victory. It was the first of two homers he hit in limited playing time, to go along with 12 RBIs, a .270 average, and 15 stolen bases.

Chuck Tanner became the Pirates’ manager in 1977, and like a kid with a chemistry set, had more speed to play with than his predecessor. The Pirates lineup, which included Moreno, holdovers Rennie Stennett and Frank Taveras, and new third baseman Phil Garner, turned the basepaths at Three Rivers Stadium into the Pittsburgh Motor Speedway, as the Bucs stole 260 bases as a team to lead the major leagues — the Astros were second with 187 — with Moreno contributing 53 to the total.9

As good as that number was, Moreno’s rookie season was a disappointment to the Pirates. They didn’t expect huge numbers or much power from him, but his .240 batting average was below team expectations. Ever the optimist, Tanner expected great things from Moreno in the future: “Moreno hasn’t even begun to realize his potential,” Tanner said.10

Moreno got off to a good start at the plate in 1978 in part because he was more familiar with the strike zone and also because he stopped trying to pull the ball. “I try to hit everything on the ground and to left and left-center field,” he said. “I’ve been staying away from bad pitches because I’m not trying to pull the ball.”11 That approach worked in the first month of the season — he had a .286 average on May 1, but a horrible slump that month (16-for-107, .150) dropped his average to .198 by May 31. He remained in the batting order due to his speed and defensive ability. He worked his average back up to .235, and more than doubled his walk total for the season, to 81 from 38 in 1976. His biggest achievement of the season was to lead the majors in stolen bases with a team-record 71; he also scored 95 runs.

The Pirates’ brass still wanted Moreno to improve his hitting. Every “Tom and Dick” was trying to give him advice, which only increased his anxiety level, so after the season they sent him to see former Pirates skipper Harry “The Hat” Walker, who was coaching at the University of Alabama. Walker had a good reputation with the Pirates as a hitting instructor. The San Francisco Giants traded 25-year-old Matty Alou to Pittsburgh after he hit .231 in 1965. Under Walker’s tutelage, Alou won the batting title in 1966 with a .342 average, and maintained that batting stroke the rest of his career, as his lifetime .307 mark will attest.

Walker focused on getting Moreno to swing down on the ball and put it on the ground more. Moreno proved to be a very good student, as he set career highs in 1979 in batting average (.282), runs (110), hits (196), home runs (8), and RBIs (69) He also won his second consecutive NL stolen-base crown (77 steals). Defensively, he also showed how his speed permitted him to reach a lot of fly balls, as he led the league in putouts by a center fielder with 489, significantly more than Gold Glove winner Garry Maddox of the Phillies, who nabbed 425. Moreno also showed that just because he could reach more balls, it didn’t mean that he always caught them, as he led National League center fielders in errors with 13. The Pirates reached the World Series that year, and Moreno showed he could produce in the clutch; his 11 hits in the fall classic were just one below the totals of Series co-leaders Garner and MVP Willie Stargell as the Pirates defeated the Baltimore Orioles in seven games. Six of those hits came in the last two games, to help the Bucs come back from a 3-1 deficit. Moreno caught the final out in Game Seven.12

The Pirates had won the National League East by two games over the Expos. That offseason, the Montreal brass decided to fight fire with fire, or, more precisely, speed with speed. They acquired basestealer extraordinaire Ron LeFlore from the Detroit Tigers. LeFlore and Moreno had a season-long race for the National League’s basestealing crown in 1980. The competition went right to the wire, with LeFlore edging Moreno out by one, 97 steals to 96. Moreno’s steal of second in the first inning of a 5-1 loss in Houston on August 20 was historic. It was his 70th steal of the year, making him the first player since 1900 to have three consecutive seasons with 70 or more steals.13

For all his basestealing wizardry, it seems that Moreno should have gone back to that cat called “The Hat” for a refresher; the lessons he applied so well in 1979 didn’t carry over into 1980, as he hit only .249, with 2 home runs and 36 RBIs. The lower numbers were due to several factors. One was a midseason finger injury suffered when he jammed the little digit of his left hand while sliding into a base on a steal. The injury, although painful, still allowed him to play, but he had difficulty gripping the bat and couldn’t bunt for base hits. Another, according to Moreno, was his dissatisfaction with his contract situation.

“I was mad about my contract and the front office,” Moreno said. “I said okay to a one-year contract in spring training because (Pirates management) said we’d talk about a five-, six-year contract later. Then they changed their minds and say no.”14

Tanner said that Moreno’s defensive abilities were far more important than his offensive output. He had a one-of-a-kind defensive triple crown in 1980, leading National League center fielders in putouts (481), assists (15), and outs made (560). “The last thing you look at with Moreno is his hitting,” Tanner said. “I played him every day when he hit .235 and I would today. He takes so many hits away with his glove.”15

The distractions that reduced Moreno’s offensive production in 1980 were dealt with in the offseason. He had surgery on his finger, and signed a one-year deal after playing without a contract the previous year. He was confident going into spring training for the 1981 season, and even predicted that he would hit .300. Early on it became evident that Moreno was not going to reach that goal; his average stood at .203 by May 17. He slowly started hitting again by that point, and by June 10, the date of the first in-season strike in baseball history, he was hitting .261. He began hitting when play resumed on August 10, and had his average up as high as .291 by September 20 before finishing with a .276 mark with 1 home run and 35 runs batted in after starting all of Pittsburgh’s 103 games. His basestealing fell off significantly; his 39 thefts were second in the league, but far below the league-leading total of Expos rookie Tim Raines, who had 71.

Raines’s overwhelming win in the stolen-base race caught Moreno flatfooted, so when spring training rolled around for 1982, Moreno promised to take back his title. “He [Raines] really surprised me last year,” Moreno said. “I am going to do my best to steal over 85 bases. That’s what’s on my mind now.”16

Tanner even planned to help Moreno reach his goal by having Mike Easler bat second in the order behind him. Tanner reasoned that Easler, being a good fastball hitter, would see a lot of slow stuff, which would make it easier for Moreno to get a good jump. It was a good idea in theory, but Easler’s woeful .143 average after nine games didn’t discourage pitchers from throwing him anything. Tanner dropped Easler to sixth in the order starting with game 10 and kept him in the lower part of the lineup for the rest of the season.

The failed experiment did not prevent Moreno from having a productive year on the basepaths, as he stole 60 bases, third in the National League behind Raines (78 steals) and Lonnie Smith of the Cardinals (68). At the plate he had a typical Moreno season, with a .245 batting average, 3 home runs, and 44 RBIs.

Moreno was obviously very busy during the baseball season. But he was also involved in the community as local honorary chairman of the National Hemophilia Foundation, a cause that was important to him because he has a nephew with the condition, On April 18, 1982, he allowed himself to be roasted by his teammates at a fundraising dinner for the organization. The zingers were mild — Kent Tekulve said that Panama “had big, ugly tigers. …Omar had to be fast or he was lunch” — but the event was a sign of how highly his fellow Pirates thought of him.17

Moreno was a free agent after the season, and although his agent, Tom Reich, negotiated with Pittsburgh, the two sides were unable to reach a deal. On December 10 he signed a five-year, $3.25 million contract with the Houston Astros. Interestingly, Pirates general manager Pete Peterson felt that Reich did not handle the negotiations well for his client, and that the Astros’ offer was not significantly more over the life of the contract than what Pittsburgh was willing to pay.

“If the Houston figures are correct, and I see no reason to not to believe they are, Moreno left for only — and I stress only — $25,000 a year,” Peterson said. “If he wasn’t happy in Pittsburgh, will he be happier in Houston for $25,000 more a year?”18

That question, while rhetorical, proved to be prophetic. Houston signed Moreno to bolster an offense that scored 569 runs in 1982, 11th in the National League.19 By the midway point of the 1983 season, the same batting numbers that were just fine in Pittsburgh weren’t quite up to snuff in Houston. By July Astros manager Bob Lillis had decided to bench the left-handed-hitting Moreno against certain southpaw pitchers. This didn’t sit well with Moreno, who never even bothered to look at the lineup card in Pittsburgh because it was a given that his name would be there. After watching two games from the visitors’ dugout at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium in late July, the normally quiet Moreno demanded to be traded. Ultimatums don’t go over well with Houston fans, and many of the 18,781 at the Astrodome that evening booed him mercilessly when he returned to the Astros lineup on July 27. It was clear at this point that the situation was untenable, so on August 10 the Astros traded Moreno to the New York Yankees for switch-hitting outfielder Jerry Mumphrey. Moreno was happy with the deal. “The Yankees have a good chance to win the pennant and I can help them,” he said.20

Moreno played regularly in center field with the Yankees, but batted primarily eighth or ninth. The Yankees finished in third place in the AL East with a 91-71 record, seven games behind the eventual world champion Baltimore Orioles. For the year, Moreno batted .244, with 1 home run and 42 RBIs. While his numbers at the plate were typical, his numbers on the basepaths were not. He stole 37 bases (30 with Houston, 7 with New York), which is a good total for most players, but for Moreno it was his lowest total since he became an everyday player in 1977.

It was clear to Moreno early in spring training that the 1984 season was not going to be fun, and that he might have made a mistake leaving Pittsburgh. One reason was that Yankees manager Billy Martin, who coveted the speed-and-defense playing style at which Moreno excelled, had been fired, and replaced by the long-ball-loving Yogi Berra.

“They [the Yankees] have enough power. But they don’t believe in speed here,” he said during spring training. “There was nothing like Pittsburgh for me.”21

Moreno played in only 117 games in 1984, and in 11 of those he was a late-inning defensive replacement. A slow start — he was hitting .184 after 14 games — earned him a seat on the bench for 17 of 19 games in late April and early May, the longest stretch of inactivity in his career. For the year, he hit .259, with 4 home runs, 38 RBIs, and 20 steals.

The Yankees traded for speedy basestealing outfielder Rickey Henderson from the Oakland A’s after the 1984 season, sending a not-subtle-in-the-least message to Moreno that he couldn’t expect much playing time in an outfield of Henderson, Dave Winfield, and Ken Griffey Sr. in 1985. In fact, he got into only 34 games and was batting just .197 before the Yankees gave him his unconditional release on August 16.

After being inactive for two weeks, Moreno received a call from the eventual World Series champion Kansas City Royals. Their regular center fielder, Willie Wilson, had been hospitalized after a bad reaction to a penicillin injection administered by the Texas Rangers’ team physician. On September 5, in just his second game with the Royals, Moreno had an inside-the-park home run in the first inning followed by a two-run triple in the eighth to spark Kansas City to a 4-1 victory over Milwaukee. During their five-game sweep of the Brewers, Moreno was 9-for-17 (.529) with two home runs and eight RBIs. He batted .243 in 24 games with the Royals, but was not on the postseason roster.

The Royals cut Moreno after the season, but early in 1986, the Atlanta Braves, with Moreno’s old friend Tanner managing, signed him to a minor-league contract. Moreno played well enough during spring training to earn a roster spot, and went north with the big-league club. He served in a part-time role, primarily in right field, playing in 118 games, hitting .234 with 4 home runs and 27 RBIs. He stole 17 bases but was caught 16 times. The Braves released him after the season and his baseball career was over.

After finishing in baseball, Moreno and his family, consisting of wife Sandra, son Omar Jr., and daughter Leury, returned to Panama. For many years he and Sandra ran the Omar Moreno Foundation, which made it possible for poor children to play baseball. In 2009, new Panamanian President Ricardo Martinelli asked Moreno to serve as Secretary of Sport, where he represented Panama internationally and oversaw the country’s athletic programs.

Upon finishing that assignment, Moreno continued working with underprivileged children in Latin America. His ability as an offensive catalyst for the Pirates earned him election into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame in 2015. As of 2016, he was also active in the Pirates’ alumni association and served as a Pirates coach during spring training. He was also busy with two granddaughters, Gaby and Camila, who kept him wrapped around their fingers.22

Last revised: August 1, 2016

This biography appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used:

Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail.

McCollister, John. Tales From the 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates: Remembering The “Fam-a-lee” (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005).

Salina (Kansas) Journal.

Vivatropica.com.

Notes

1 “Moreno Pirates’ Quiet Thief,” Spokane (Washington) Spokesman-Review, July 10, 1979: 23.

2 Raybourn had a very good eye for talent — he also signed Manny Sanguillen and Rennie Stennett for the Pirates and later signed Mariano Rivera for the New York Yankees.

3 The Mets were last with 32.

4 Dave Brown, “Bucs Optimistic but “Shortcomings” Remain,” Somerset (Pennsylvania) Daily American, January 24, 1976: 9.

5 Jed Weisberger, “Bucs Face Crucial Year as Phils Pose Challenge,” Indiana (Pennsylvana) Gazette, April 10, 1976: 38.

6 A.L. Hardman, “Fast-Moving Moreno Leads Speedy Trio at Charleston,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1976: 43.

7 Charley Feeney, “Pirates, Phils Split — But Nothing Is Settled,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 5, 1976.

8 Charley Feeney, “Moreno Gives ‘Steal’ to Pittsburgh,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1976: 12.

9 Tavares led the league with 70 steals, while Garner had 32 and Stennett had 28.

10 “Bucs Reflect on 1977 Campaign,” Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Morning Herald-Evening Standard October 5, 1977: 5.

11 Charley Feeney, “Waiter Moreno Not Looking for Tips,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 5, 1978: 13.

12 One of Moreno’s prized possessions was a loud whistle his wife, Sandra, blew frequently to encourage him during the Series.

13An article in the August 19 edition of the Tyrone (Pennsylvania) Daily Herald (“Division leaders Pitts., Houston Battle Tonight”: 7) noted that milestone. Moreno had 69 steals at the time.

14 Dan Donovan, “He’s Omar The Thrillmaker,” Pittsburgh Press, July 27, 1980: D-2.

15 Ibid.

16 Ralph Bernstein, “Moreno Eyes Thievery Title,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, March 25, 1982: 13.

17 Dan Donovan, “It’s a Toast for Moreno,” Pittsburgh Press, April 20, 1982: C-1.

18 Charley Feeney, “Moreno Jumps Pirates for Astros,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 11, 1982: 9.

19 The Cincinnati Reds were last in the league with 545 runs scored.

20 “Moreno Dealt to Yankees,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 11, 1983: 23.

21 Bob Smizik, “Homesick: Yankee Sub Moreno Wishes He Never Left Pirates,” Pittsburgh Press, March 19, 1984: D-3.

22 Email to author from Leury Moreno, January 16, 2016.

Full Name

Omar Renan Moreno Quintero

Born

October 24, 1952 at Puerto Armuelles, Chiriqui (Panama)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.