Max Patkin

The Clown Prince of Baseball

Did 5,000 gigs

For 50 years he shared the bill

With circus dogs and talking pigs

And by the 9th inning

He’d be back at the motel

With an early morning wake-up call

And the next night he’d be someplace else.1

Max Patkin never made it to the big leagues as a player. But that did not stop him from spending his life entertaining fans and players with his antics as he traveled the country. Patkin became the second “clown prince of baseball” and a fixture on ballfields across the country ever summer for 50 years after his brief playing career ended.

Max Patkin never made it to the big leagues as a player. But that did not stop him from spending his life entertaining fans and players with his antics as he traveled the country. Patkin became the second “clown prince of baseball” and a fixture on ballfields across the country ever summer for 50 years after his brief playing career ended.

Patkin was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on January 10, 1920. His parents were Samuel and Rebecca Patkin, immigrants from Russia who settled in Philadelphia to be close to relatives. His father held several jobs during Patkin’s childhood: night clerk in a hotel, delicatessen owner, salesman for check writers, which were machines used at the time to prevent checks from being forged. His mother was a homemaker who took care of Patkin and his siblings while his father was away.

Max was the oldest of three children, with a brother Eddie and a sister Ruth. Patkin often fought with Eddie. “The kids on the block were always encouraging me and Eddie to fight. So, we would get on the sidewalk and we’d spar swapping punches, slaps.”2 But he was always protective of Ruth while they were growing up.

When Max was eight, his father took him to a game at Shibe Park, Patkin saw Jimmie Foxx play and fell in love with baseball. “I wanted to be a major league ballplayer. I’d sit at dinner with my baseball hat on. I never took it off until I went to bed, then I’d put it under my pillow with my glove.”3

He showed signs of being a clown as early as high school. He wrote in his autobiography that “I might have been the only athlete at West Philadelphia High School to flunk gym. The gym teacher didn’t like me. He once gave me a VVVP rating. That stands for very, very, very poor.”4

Patkin started out as an outfielder but the baseball coach turned him into a pitcher when he saw how much he could lift his leg when throwing the ball. He had hoped to play baseball in college but his grades were not good enough so he attended Brown Prep in the hope that he might improve academically and earn a baseball scholarship.

He pitched for Brown Prep for two years and lost just one game. Unfortunately, he did not improve his academic standing, even becoming “the only guy who flunked study hall in high school.”5 Patkin also played basketball during his time at Brown Prep but his inability to handle the ball shortened his basketball career.

His love of baseball led him to find ways to play all year. He pitched for McCall Post in the local American Legion league. His team won the 1936 state championship. Patkin also played for an amateur team named Wertz-Olney where he faced Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Eventually, Patkin received enough notice to earn tryouts with several major league teams. None of the teams offered him a contract, so he continued to pitch amateur ball. Finally, the Chicago White Sox signed him and assigned him to their Waterloo, Iowa, team. When Patkin arrived in spring training, he learned that the White Sox had sold his contract for $100.

He was sent to the Class D Wisconsin Rapids of the Wisconsin State League for the 1941 season. He finished with a 10-8 record, 134 strikeouts and 95 walks in 178 innings. Patkin remembers that he frequently threw wild pitches from the mound and one time “I let one go and it got away from me. Took off, over the batter’s head. It zips into the press box and hits the back wall. It bounces back and nails the back of this writer’s head, knocking him cold.”6

When the United States entered World War II that winter, Patkin joined the Navy. He was assigned to former boxer Gene Tunney’s unit in Honolulu as a physical instructor. Bobby Riggs was also assigned to a unit in Honolulu at the time. Riggs challenged Patkin to a table tennis match and was so confident that he gave away 14 points. Patkin beat him several times. “We played day and night for three days until he got shipped out. He ended up owing me $2,000, and the other guys wouldn’t let him out of there until he paid up. He paid me $500, and every time I saw him after that, he bought me dinner, although not $1,500 worth of dinners.”7

Patkin eventually played on the Navy baseball team in Hawaii. When he pitched against the Army Air Force team, Joe DiMaggio was one of their players. When DiMaggio sent one of Patkin’s pitches out of sight, Patkin followed DiMaggio around the bases, mimicking his trot. He often said that this was the start of his career as a baseball comedian.8

After Patkin left the service in 1945, he returned to baseball. He was signed by the Cleveland Indians and sent to the Class-A Wilkes-Barre Barons (Eastern League) for the 1946 season. Patkin pitched five games and had a 1-1 record when he came down with tendinitis in his shoulder. The injury ended his playing career but it quickly led to another career as a baseball clown. Patkin started performing during games, entertaining the crowd as he distracted the opposing team.

During an exhibition game with the Philadelphia Athletics, the stoic Connie Mack even began laughing at Patkin’s antics in the coaching box. “That’s when I knew I was funny, when I made Connie Mack laugh,” he said.9

When Patkin was released by Wilkes-Barre, he received a call from the general manager of the Harrisburg Senators. He was offered $100 to do his routine during an exhibition game against Cleveland. Patkin’s show was “terrific, except that I [tore] a ligament in my knee. I was coaching first and I threw my leg up in the air. Threw it so high that I ripped my knee.”10

Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck got wind of Patkin’s coaching show.. Originally, Veeck wanted him to perform along with Jackie Price, another former player who was also touring the country as a baseball clown. Lou Boudreau, the Cleveland manager, convinced Veeck to let Patkin coach for the first two innings of every game to drive the other team crazy.

Patkin eventually signed a baseball contract for $1 and a personal services contract for $650 per month. Veeck once said of Patkin, “[H]e looks like he was put together by somebody who forgot to read the instructions.”11 Patkin remained a regular with the Cleveland Indians until midway through the 1947 season when Veeck decided that the team had become competitive and didn’t need any distractions.

His stint with the Indians gave Patkin lots of exposure. Although he quickly earned a reputation as a baseball clown, he was not the first “clown” to perform at baseball games. Al Schacht, who played for three seasons with the Washington Senators 1919-1921, was the first to use that moniker. After his career was shortened by an injury, he performed at baseball games and became well known for his comedy routine. Schacht always wore a formal tailcoat over his baseball uniform. When Patkin joined the ranks of baseball clowns, he set himself apart from Schacht by always performing in a baseball uniform.

Although Patkin saw his time in the Indians coaching box decrease with each year, he stayed with the Indians until Veeck sold the team in 1949. At that time he made the decision to start barnstorming across the country to bring his act to any team or location that would hire him.

Most of Patkin’s performances were at baseball games but he performed anywhere that offered him a paycheck. He toured with the Harlem Globetrotters at one point. Patkin remembers that in the middle of his routine with the Globetrotters, he accidentally mooned the audience and brought down the house. “I shoulda kept it in my act,” he said.12

He also traveled overseas for the State Department and performed at ice shows, changing costumes to fit the occasion. Early in his career, he was at a sports trade-show with Jim Thorpe. Thorpe gave Patkin a baseball glove that he used in his act until he retired.

On a State Department tour of Europe in 1953, he was introduced as “the handsomest fellow in baseball.” He wrote in his autobiography that the “GIs loved it. I’d do this skit, pretending to be a pitcher facing the New York Yankees. I’d be out there, struggling, trying to get out Phil Rizzuto, Billy Martin, Yogi Berra, and the other Yankees. I’d argue with the umpire, always give up a bases-loaded homer to Berra and then trudge to the showers.”13

Patkin started dating Judy Obendorf in 1953. Obendorf was 15 years younger than Patkin. They eventually married in 1960 when Obendorf’s mother confronted him and told him that he “was wasting her daughter’s time, and I ought to marry her or disappear.”14

After trying for several years to have a child, they eventually adopted a baby girl, Joy. Patkin was not there very often when his daughter was growing up. “I’d book 10- or 12-day trips and Joy got bitter, me being away so long. I tried to make up for it when I was home.”15

Patkin’s marriage eventually fell apart. He finally left his wife when she attacked him with a hammer, splitting open his skull. He recounted the story over the years, saying that his wife “ran into the kitchen to get a knife and started after me again. Then my daughter jumped in, grabbed the knife, and wrestled it away from her mother.”16

When his marriage dissolved, Patkin gave his wife everything that she asked except for custody of his daughter. When he was eventually awarded custody of Joy, the two of them moved in with his brother Eddie until he was able to get back on his feet. He also said later that “[w]hat really hurt, though, was that in all the years I knew her, she never once saw me perform. Not once. For all she knew, I was an airline pilot.”17

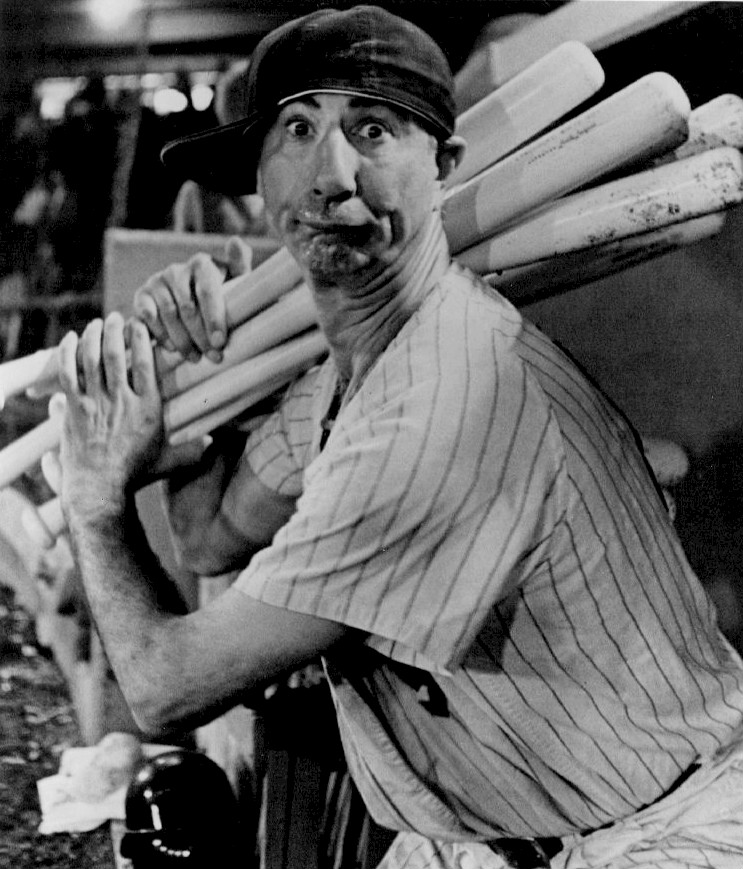

By the mid-1950s, Patkin had developed his character. He always performed in a baggy uniform with a question mark sewn on the back. His cap was tilted sideways. His toothless face could contort in numerous ways that always captivated the crowds.

Sometimes the managers or the owners were not happy when he performed. Some managers thought that he distracted too much from the game. “In the beginning, when I was coaching in the minors, some managers thought what I did was sacrilegious. Gene Mauch was the worst. He blew his top every time, tried to refuse to let me perform. He got me four times. Well I’ll be a s.o.b. if he didn’t lose all four games.”18

Patkin said that his routine never affected the outcome of any games although he was accused of doing that on various occasions. Once when he was doing his routine in the third base coach’s box for the Blue Jays, the Orioles Jim Palmer was on the mound. He was pitching to John Mayberry when Patkin shouted ‘Fastball!’ just as Palmer was throwing the ball. It turned out to be a fastball and Mayberry knocked it out of the park for a home run. “I’m standing in the box, and Palmer is staring at me with those penetrating blue eyes of his,” Patkin remembered.19

Patkin said that his routine never affected the outcome of any games although he was accused of doing that on various occasions. Once when he was doing his routine in the third base coach’s box for the Blue Jays, the Orioles Jim Palmer was on the mound. He was pitching to John Mayberry when Patkin shouted ‘Fastball!’ just as Palmer was throwing the ball. It turned out to be a fastball and Mayberry knocked it out of the park for a home run. “I’m standing in the box, and Palmer is staring at me with those penetrating blue eyes of his,” Patkin remembered.19

His routine varied from night to night but it always ended with a visit to the batter’s box. Patkin would dodge a brushback pitch. Then he would take a fastball over the heart of the plate, pushing the catcher over as he tried to avoid being hit. Finally, Patkin would hit the ball and run to third base where he would be tagged out and engage in an animated argument. Eventually he would be tossed out of the game. “It was a corny act but the fans liked it,” he said.20

Patkin developed a host of routines that he would vary as he traveled around the country. He carried a miniature glove that he would use when playing infield. Patkin often imitated the first baseman’s warm-up ritual. Sometimes he would show the third-base coach how to give signs while dancing to ‘Rock Around the Clock.’ One of his most popular moves was taking a long drink of water and then spewing a geyser of water high in the air.

Over the course of his career, Patkin usually performed at least 80 shows each baseball season. He is proud that he never missed a performance. Once he jumped off a burning plane after it landed in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in order to make a date. Another time he rode in a cab for 300 miles on a flat tire to get to the ballpark for a performance.

Patkin was also a natural story teller and he had one about almost every ballpark that he visited. One night in Eugene, he was doing his catching routine but the pitcher didn’t realize it. [He] throws a 90 mph fast ball. “It sails just past my head and hits the backstop with a thud. It was supposed to be a blooper. If it had hit me between the eyes, they would have had to scrape me off the plate with a butter knife.”21

Sickness did not stop Patkin from fulfilling a contract to perform. “It was in Monterrey, Mexico and I had Montezuma’s revenge. All of a sudden, the guy on first base steals second. No big deal, but then the first baseman steals second. And the umpire steals second. I’m standing there all alone when I realize I’ve had an accident in my pants.”22

Patkin performed before teams had their own mascots such as the Phillie Phanatic and the San Diego Chicken. But unlike mascots, he never wore a costume. His rubber nose and elastic face, his baseball cap always on sideways, his tongue out and the ability to twist and turn his body always brought smiles to the faces in the crowd.

Patkin loved to perform and was willing to do it in front of any size crowd. He said that his favorite performance was the time that he did his routine in front of 80,000 fans in Cleveland. Patkin also claimed that he once performed for just four people. According to his autobiography, it was in 1969 on the Sunday afternoon the astronauts landed on the moon. “The general manager asked me if I would cancel, and I didn’t want to blow the pay day, so I said I’d go on. [The general manager] said he’d scatter some television sets around the ballpark, but only four people showed up, and two of them were the parents of the starting pitcher.”23

Whenever Patkin arrived in a town to put on his show, he would come to the ballpark early to meet the players. “I go over my skits in the clubhouse. As long as I don’t make anybody look like a fool, except myself, you understand, then I get the cooperation. They like me because I bring people into the ballpark and I make people laugh – kids and families. The greatest pleasure I have to this day is to make families laugh.”24

He met many notables during his long career. When he was performing in Denver in 1988, George H.W. Bush was at the game. Bush was throwing the ball around the infield and Patkin was doing his routine in the coach’s box where he imitates the first baseman. Patkin wrote in his autobiography: “We hadn’t rehearsed, the whole thing was a surprise. So, I’m whispering to him to take off his hat, and he does it. I tell him to stretch his arm and he does it. Finally, the inning ends and we get a big hand.”25

Bull Durham provided Patkin with an even bigger audience when it came out in 1988. Ron Shelton, the film’s director, remembered seeing Patkin perform when Shelton was playing minor league ball in California. Patkin not only performs his act on the big screen but has one of the more memorable lines in the film when the character of Annie Savoy asks him why he keeps performing. He tells her, “Annie, I love this game of baseball, I truly love this game.”26

Before his big screen debut, Patkin appeared on television. He was on “To Tell The Truth” and the panel had to guess the real Max Patkin. “I brought three uniforms and they put the other two on two very normal looking human beings. I couldn’t believe it when only one panelist, Peggy Cass, guessed me as the real Max Patkin.”27

Late in his career, Patkin was inducted into the Clown Hall of Fame. He also received the Lifetime of Laughter Achievement Award from the organization that is given to those who have helped to make the world a happier place through their antics.

Patkin kept performing until 1993, when health issues forced him to retire at 73. His brother Eddie passed away the next year, and Patkin suffered depression from his loss.

Although Patkin had retired from performing on the diamond, he stayed active in a variety of ways. While he was videotaping a television spot in the spring of 1999, a panhandler stole $35 from him. Patkin asked the judge to grant the man leniency and presented the robber with a copy of his autobiography. “I thought that ought to be the sentence. To read my book,” he said.28

He passed away on October 30, 1999 from an aortic aneurysm, in Easton, Pennsylvania.

Legendary broadcaster Harry Caray summed up the magic of Max Patkin this way: “If you wanted to get away from the high-salaried big names of baseball, who’s brought more joy throughout the land than Max Patkin? He’s sure given his life to baseball in places where it really needed it, in small places and minor league towns.”29 He will always be remembered for the smiles that he brought to fans in places large and small.

His uniform was baggy

He had gigantic feet

His hat was always cock-eye

And he had but a few teeth

And a schnozz as big as Baltimore

And a heart as big as Devon

Max Patkin made the children laugh

And for that he’s gone to Heaven30

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Retrosheet.org websites for player, team, and season pages, and other pertinent material.

Notes

1 Chuck Brodsky. Gone to Heaven. CD. Recorded August 8, 2000. .

2 Max Patkin, The Clown Prince of Baseball (Waco, Texas: WRS Publishing, 1994), 19.

3 Richard Goldstein, “Max Patkin, 79, Clown Prince of Baseball,” New York Times, November 1, 1999, B8.

4 Patkin, 20.

5 Patkin, 23.

6 Patkin, 26.

7 Steve Wulf, “Max,” Sports Illustrated, June 8, 1988.

8 Goldstein.

9 Wulf.

10 Patkin, 31.

11 Wulf.

12 Ibid.

13 Patkin, 116-117.

14 Patkin, 73.

15 Patkin, 76.

16 Patkin, 78.

17 Wulf.

18 “Max Patkin, Clown Prince of Baseball,” MiscBaseball.wordpress.com, August 9, 2009.

19 Wulf.

20 Goldstein.

21 Patkin, 85.

22 Bill Plaschke, “This Clown Not Laughing Inside : Patkin’s Looks May Be Funny to Others, but Not to Him,” Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1990.

23 Patkin, 6.

24 Paul Willistein, “Max Patkin ‘Clown Prince Of Baseball’ Reminisces,” The Morning Call (Allentown, PA), June 12, 1988.

25 Patkin, 94.

26 Patkin, 95.

27 Patkin, 100.

28 Goldstein.

29 “Patkin, Baseball’s Clown Prince, Hopes for Spot in Hall of Fame,” Washington Post, April 22, 1987.

30 Brodsky.

Full Name

Max Patkin

Born

January 10, 1920 at West Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

October 30, 1999 at Paoli, PA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.