Fred Hopke

Soon after he signed his first professional contract, Fred Hopke declared his ambition in answer to a questionnaire: “First string major league player.”1 The quest for his grail consumed 10 years of his life, but he never got beyond spring training. Love for the game stuck out all over him. “Fred Hopke would wear a baseball uniform 24 hours a day if you’d let him,” said one of his managers, Kerby Farrell.2

Soon after he signed his first professional contract, Fred Hopke declared his ambition in answer to a questionnaire: “First string major league player.”1 The quest for his grail consumed 10 years of his life, but he never got beyond spring training. Love for the game stuck out all over him. “Fred Hopke would wear a baseball uniform 24 hours a day if you’d let him,” said one of his managers, Kerby Farrell.2

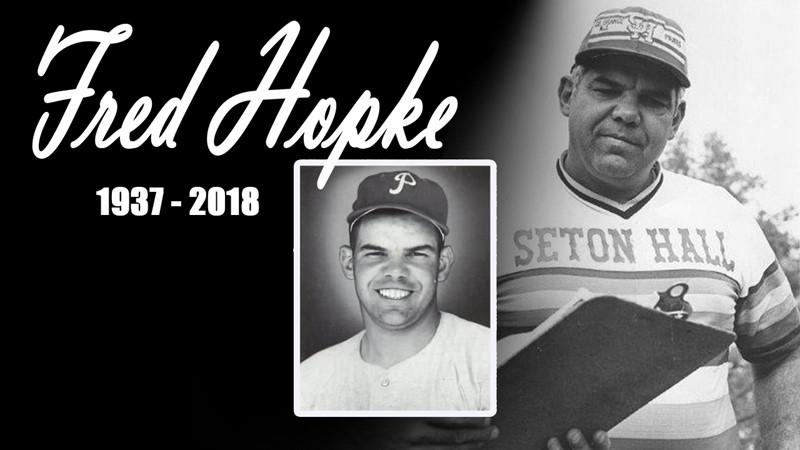

Love for the game led him to spend nearly two decades without pay as a hitting coach for Seton Hall University. His pupils included Hall of Famer Craig Biggio, 1995 AL MVP Mo Vaughn, and major leaguers John Valentin and John Morris. Biggio paid tribute to Hopke in his induction speech at Cooperstown in 2015: “He brought a pro-style approach to the program. He’s the first person that taught me how to work myself through an at-bat.”3

Hopke (pronounced “HOP-key”) learned to love baseball as a boy in Newark, New Jersey, when his truck-driver father took him to New York to see the big leaguers play. Frederick Lawrence Hopke was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on January 25, 1937, the second son of Fred and Rita Hopke. He was a three-sport standout at Irvington Vocational-Technical High School in Irvington, New Jersey, a 1,000-point scorer for the basketball team that won the 1955 state championship. His baseball talent lit up the sandlots around Newark.

After graduation, Phillies scout Chuck Ward signed him for a reported $4,000, the largest bonus the club could pay without having to keep him on their major-league roster for two years. At 19, he started on the bottom rung of pro ball in Tifton, Georgia, in 1956. It was the first stop on a frustrating odyssey that wound through 10 US cities and towns as well as Puerto Rico, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Canada.

The 6-foot-2, 215-pound left-handed first baseman loomed like a giant over the teenagers in the Georgia-Florida League.4 Hopke belted 20 home runs under the dim Class-D lights and made the first of five all-star teams.

That earned him an invitation to the Phillies’ early spring camp in Clearwater, Florida, a school for the most promising prospects. In 1957 he moved one step up the ladder to the Class-C Pioneer League at Salt Lake City. He broke out with a .337/.413/.474 batting line and walked nearly twice as often as he struck out. After the season he married his hometown girlfriend, Phyllis Shubsda.

His big year put him on the fast track with a promotion to the Triple-A Miami Marlins. One day during 1958 spring training, a Cadillac rolled through the gates and across the outfield. At the wheel: Satchel Paige. The 51-year-old legend, in his final full season in Organized Baseball, struck up an acquaintance with his 21-year old teammate.

“He said, ‘Do you fish?’” Hopke recalled. “[I said,] ‘I love fishing.’ I’d never fished in my life. So he took me and we went out to the causeway and he gave me a big fishing pole. I threw it under the pier. You know, my first cast. He said, ‘Oh, let me outta here.’ What a man he was. Everything they say about that guy is true.”5

Hopke impressed manager Kerby Farrell. “If desire has anything to do with it,” Farrell said, “Fred isn’t too far away from playing first base for the Phillies. In all of my years of managing, I’ve never seen a player with more desire.”6 But soon after Opening Day, the young first baseman fell victim to a freak injury. As he slid into third, umpire Joe Linsalata stepped on his hand and cut it open. Whether because of the injury or the mysteries of International League pitching, he batted .205 with just one home run in 28 games. He was sent down to Class-A Williamsport, Pennsylvania, where he found the Eastern League more accommodating. He hit .284 in a pitcher-friendly environment.

After a third straight trip to the Phillies’ early camp the next spring, Hopke went back to Williamsport. The 1959 team, known as “Lucchesi’s Crazies” after manager Frank Lucchesi, spent much of the season in first place before slipping to third at the end. Hopke was the hitting sensation with 30 homers, a league-leading 130 RBIs, and .316 batting average. The Phils promoted him to their 40-man roster and brought him to major-league spring training in 1960.

He was cut after a month and rejoined Farrell with the Triple-A club, now in Buffalo. This time he was more than ready for the International League; his average climbed to .366 in June. Under orders from Phillies management, he had shed 25 of his 245 pounds during the winter with his wife’s help. “I love to eat,” he said, “but Phyllis wouldn’t give me seconds.” Farrell was still beating the drum for him, saying the left-handed swinger “reminds me of everything I ever heard about Gehrig.”7

The Phillies didn’t have Gehrig, but they did have a powerful young first baseman in rookie Pancho Herrera, who had hit 37 homers for Buffalo the previous year. On June 15, 1960, Philadelphia traded Hopke with outfielders Wally Post and Harry Anderson to Cincinnati for outfielders Tony Gonzalez and Lee Walls.

Hopke’s new employers left him in Buffalo, where he was named to the all-star team. He didn’t get to play in the game; a few days before, a bad hop hit him in the face, requiring six stitches. In late July the Reds called up their other Triple-A first baseman, Gordy Coleman, and tapped Hopke to replace him in Seattle.

With just over a month left in the season, Hopke decided not to bring Phyllis and their baby son, Fred Jr., with him to the West Coast. He joined a new team in a new organization on the opposite end of the continent and spent his nights alone in a hotel. He collapsed into the worst slump of his life. “When I went 0-for-10 I began to worry,” he said. “As it got worse, so did I. Soon, I wasn’t able to sleep. I wouldn’t fall asleep until 4 or 5 in the morning. I became a nervous wreck. I was getting paid for work that I didn’t deliver and it preyed on me.”8

His slide reached 0-for-31 on August 21. The next day he told the team he was going home. His confidence had collapsed along with his batting average. He was tired of being nagged about his weight and was worried about his fielding as well as his hitting. Although he was just 23, he had been beating the bushes for five years and saw his goal of playing in the majors slipping away. General manager Marvin Milkes and Cincinnati GM Gabe Paul tried to talk him out of quitting, but Hopke said, “If baseball can do this to me, put me in this frame of mind, I need to get away from it.”9 Cincinnati put him on the disqualified list.

A winter at home with his family — and driving a truck — persuaded him not to give up. The Reds reinstated him and brought him to spring training in 1961. Wearing a major-league uniform, he delivered a few hits in exhibition games (full stats are not available). The club gave him some extra work with, of all things, a marksmanship instructor named John Hughes. He had the players shoot at moving targets with a BB gun. “Look at that kid batting now. That’s Fred Hopke,” Hughes told a Sports Illustrated writer. “We discovered his sighting eye was his left one. He bats lefty, and we found that when he took his stance his nose actually impaired his left-eye’s view of the ball. We figured he might do better if he turned his head more toward the pitcher. I know all this sounds odd, but this gets his nose out of the way and he can see better.”10

It not only sounded odd, it didn’t work. Sent to Triple-A Indianapolis, Hopke didn’t hit, no matter what the position of his nose and eyes. He found himself on the bench for the first time. He did little more than pinch-hit until midseason, when the regular first baseman, Don Pavletich, moved behind the plate. The two shared the first-base job from then on. Hopke finished at .225 with just six homers in 84 games.

Despite his poor showing, the Reds called him up to the expanded big-league roster in September, but it was a formality; GM Bill DeWitt said he would only report to the team in case of emergency.11 The Reds, driving toward their first pennant in 21 years, were in no position to try out rookies. During the offseason Cincinnati sold him to Triple-A Syracuse on a make-good basis. The Chiefs could give him a trial before paying for him.

Again he was a part-time player. He made himself useful by catching one game when both the team’s catchers got hurt. Hopke had his own left-handed catcher’s mitt, which he used to warm up pitchers in the bullpen. He was hitting .380 a month into the season when Syracuse traded him to the Atlanta Crackers, also in the International League.

The trade gave him a regular job because the parent Cardinals had called up Atlanta’s first baseman, Fred Whitfield. Hopke hit safely in his first 11 games, but got into manager Joe Schultz’s doghouse. He weighed a reported 235 pounds, and Schultz blew up when he saw his stout first baseman enjoying cake topped with a mound of ice cream. Hopke’s hitting habits more than compensated for his eating habits. He was leading the league at .335 in mid-July and delivered nine consecutive hits in one three-game stretch.

Before the end of the month, Syracuse and Atlanta reversed their earlier trade, swapping Hopke back to Syracuse for the same man, center fielder John Glenn. (The “trade” may have been a loan to temporarily fill the Crackers’ hole at first base.) Two weeks after he returned to upstate New York, Hopke slammed three home runs in one game to beat his former teammates from the South. He finished the year at .327, third in the league, with 15 homers in 119 games.

Syracuse was a shared affiliate of two expansion teams, the Washington Senators and New York Mets. Both clubs were beginning their histories with a four-year streak of at least 100 losses and could have used a hard-hitting first baseman. (They could have used a hard-hitting anything.) The Senators relied on Bud Zipfel, Harry Bright, and 36-year-old Dale Long, while the Mets boasted Marvelous Marv Throneberry and the faded shadow of Gil Hodges. There’s no evidence that either team gave any thought to Hopke.

He was back with the Reds for spring training in 1963, but they had apparently given up on him and sold him to Richmond of the International League, a Yankees farm club. At 26, he was trapped on the Triple-A treadmill. He couldn’t repeat his success of 1962 over the next two years. Moving on to his fifth organization in 1965, he went back to Syracuse, now a Tigers affiliate.

He may have set an all-time baseball record in one game when umpire Augie Guglielmo called strike two on him. Hopke never gave umpires any lip, and now he said cordially, “Augie, in all the games I’ve played in this league and all the games I’ve seen you work, that was the first one you ever missed.”

“Hold it,” the surprised umpire shouted. “That was a ball. Make the count two balls and one strike.”12 Hopke’s unique argument had persuaded Guglielmo to do the unthinkable and change his call.

The 28-year-old Hopke was playing part-time and batting .243 in August when Syracuse released him. “This could be the end for me,” he told a writer.13

He kept trying, but didn’t find another landing spot until three years later. It took him about as far from the majors as he could get, outside the United States and outside Organized Baseball. In 1968 he signed on as player-manager of the Quebec Indians in the independent Provincial League. That job lasted only one season before Hopke left baseball at 31.

He ran an exterminating business in Hillside, New Jersey, where he had settled with Phyllis, their sons Fred and Jim, and daughter Nadine. He then worked for 17 years in a warehouse for the drug company Bristol Myers Squibb.

Hopke lived near Seton Hall University in South Orange. Head baseball coach Mike Sheppard, who had known him since they played against each other in their youth, asked him to help out as a hitting instructor for the Pirates. For most of the next 20 years, Hopke served as a volunteer, unpaid assistant coach. Seton Hall baseball was a stepchild with a meager budget. Even the head coach was a part-timer; Sheppard was a full-time professor of education.

Coach Hop’s philosophy was “see ball, hit ball.” His dedication to hitting was total. He told the players that “defense was something you did between at-bats,” according to Rob Sheppard, the head coach’s son, who played for the Pirates and succeeded his father as coach. “He knew how to motivate guys to work harder.”14

His first star pupil was John Morris, who came to Seton Hall as a pitcher, but hurt his arm and converted to the outfield. “I tried to pull everything in high school, and I hit 13-hoppers to second base all day,” Morris said. “But Fred taught me to wait on the ball, start driving the ball. All of a sudden I was hitting screamers to left-center.”15 Morris hit .418 in three college seasons, was the first-round draft choice of the Kansas City Royals in 1982, and played seven years in the majors.

Hopke stepped away from the program temporarily, but Morris urged him to return in 1987. “He told me they were a good bunch of kids but they weren’t having much fun,” Hopke said. “I went over there during the winter and watched them take batting practice. Once I saw them, I was hooked. My job is to loosen them up and make it fun.”16

The 1987 team had the best kind of fun. Seton Hall won its first Big East conference championship with a 45-10 record. The 3-4-5 batters were known as “the Hit Men”: Biggio, Vaughn, and Marteese Robinson. “During the game there’s always one of the three of us sitting next to him talking about hitting,” Mo Vaughn said, “and if there’s someone else in our seat we tell him to move.”17

Designated hitter Vaughn broke Morris’s school home-run record, was drafted in 1989’s first round by the Red Sox, and hit 328 big-league homers. Catcher Biggio went to the Astros in the first round of 1987 and amassed 3,060 hits. First baseman Robinson led NCAA Division I in hitting at .529 and shared college player-of-the-year honors with Texas pitcher Greg Swindell in 1987. Robinson was Oakland’s sixth-round pick, though his professional career topped out in Double A.

The next year shortstop John Valentin emerged as a Pirates star. “Coach Hopke is a man who can be very influential to a hitter,” Valentin said. “He feels everyone can hit and he’s a motivator. His attitude is, if you play hard, you get the results.”18 A 1988 fifth-round choice by the Red Sox, Valentin played 11 years in the majors.

Of course, the stars were few and far between, but Coach Hop didn’t slight the lesser players. “It wasn’t just the guys that made it,” said his son Jimmy, who became a high school coach. “He didn’t care if you were an all-American or a second-string kid, he’d work with you.” He was offered paying jobs at other schools, but remained loyal to Seton Hall.19

After Hopke retired from his day job and from coaching, he and Phyllis moved to Toms River, New Jersey, so he could be closer to the craps tables at Atlantic City casinos.20 He died at 81 on October 19, 2018.

He lived long enough to watch on television as Biggio took his place in the Hall of Fame and to hear his pupil say, “Thanks, Hop.”21

Acknowledgments

Photo credits: Leaf cards and Seton Hall Athletics. This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Questionnaire by William J. Weiss, baseball statistician, 1955.

2 Jimmy Burns, “Hopke Makes Strong Bid for Phillies Berth,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1958: 33.

3 “Biggio’s Hall of Fame Induction Speech,” Houston Chronicle, July 26, 2015.

4 He looked like a giant to the author, who saw a number of the Tifton club’s games at age 11.

5 Sam Zygner, The Forgotten Marlins (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 2013), 133.

6 Burns, “Hopke Makes Strong Bid.”

7 Cy Kritzer, “Hopke Fattening Up at Platter by Using Strict Diet,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1960: 29.

8 Hy Zimmerman, “Sports Hy-Lites,” Seattle Times, August 23, 1960: 16.

9 Zimmerman.

10 “Cincinnati Reds,” Sports Illustrated, April 10, 1961, https://www.si.com/vault/1961/04/10/624822/cincinnati-reds. Hughes taught the “instinctive shooting” technique championed by instructor Lucky McDaniel, whom the magazine had lionized in an earlier story. See Martin Kane, “Shooting by Instinct,” October 20, 1958, https://www.si.com/vault/1958/10/20/560260/shooting-by-instinct.

11 Lou Smith, “Purkey to Hurl Opener in ‘Showdown’ with LA,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 25, 1961: 33.

12 George Beahon, “Clubhouse Confidential,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, June 28, 1966: 1D.

13 Charlie Roberts, “Graham Blanks Crax for Chiefs, 3-0” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 26, 1965: 13.

14 Head baseball coach Rob Sheppard provided details of Hopke’s work at Seton Hall in a telephone interview on September 12, 2019.

15 “Royals’ Howser Likes Rookie Morris’ Style,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle-Beacon, March 18, 1984: 4E.

16 Ed Barmakian, “Hopke Helps Clue Seton Hitters into Average Fun,” Newark (New Jersey) Star-Ledger, May 21, 1987: 99.

17 Barmakian, “Hopke Helps.”

18 “Valentin Has Become Key Player for Seton,” Newark Star-Ledger, May 18, 1988: 69.

19 James Hopke interview, September 12, 2009.

20 Obituary, Quinn-Hopping Funeral Home. www.quinn-hoppingfh.com, accessed September 1, 2019.

21 James Hopke interview; Biggio HOF induction speech.

Full Name

Frederick Lawrence Hopke

Born

January 25, 1937 at New Haven, CT (US)

Died

October 19, 2018 at Toms River, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.