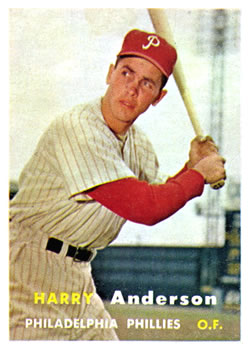

Harry Anderson

By his second year in the majors in 1958, sweet-swinging Harry (The Horse) Anderson of the Philadelphia Phillies was one of the premier left-handed power hitters in the game. But after his fourth year, he was back in the minor leagues, struggling to regain the batting stroke that had abandoned him as quickly as it had catapulted him to the top of the statistical charts. That stroke never did fully return and by 1963 Anderson was out of professional baseball entirely. What happened is the stuff of mystery, strewn with some enticing clues along the way. It is the story, like many in baseball, of tantalizing talent and unrealized potential.

By his second year in the majors in 1958, sweet-swinging Harry (The Horse) Anderson of the Philadelphia Phillies was one of the premier left-handed power hitters in the game. But after his fourth year, he was back in the minor leagues, struggling to regain the batting stroke that had abandoned him as quickly as it had catapulted him to the top of the statistical charts. That stroke never did fully return and by 1963 Anderson was out of professional baseball entirely. What happened is the stuff of mystery, strewn with some enticing clues along the way. It is the story, like many in baseball, of tantalizing talent and unrealized potential.

Harry Walter Anderson was born on a farm in North East, Maryland, near the Delaware border, on September 10, 1931. His father was Walter E. Anderson, a machine operator for the B&O Railroad.1 His mother, Blanche (née Biddle2), was a homemaker. Harry was the couple’s only child. A born athlete, Harry honed his skills on the sandlots and in American Legion ball in and around his hometown. He played softball until he went to high school at West Nottingham Academy, in Colora, Maryland. There he played third base for the baseball team, as well as toiling for the soccer and basketball teams. He still holds a share of the scoring record in basketball at West Nottingham, having poured in 54 points on one occasion.3

Following high school, Anderson matriculated at West Chester State Teachers College (now West Chester University) in Pennsylvania, where he starred as an outfielder and pitcher. At West Chester, playing against the Delaware Blue Hens at Frazer Field in Newark, Delaware, he launched what is reported to be the longest home run ever hit at the park, a 453-foot shot over the right field wall. In 1952, Anderson averaged .452, at the time the highest mark for a West Chester player.4 Looking back in 1991, Anderson told reporter Matt Zabitka of the Wilmington News Journal, “When I went to West Chester, the Boston Braves paid my tuition for the first two years. I guess they thought I was going to sign with them.”5 As it turned out, during his junior year in the fall of 1952, he signed with the Phillies for a bonus of $40,000, a princely sum at the time and the most the Phillies had spent on a “bonus baby” since shelling out $100K for Ted Kazanski a year earlier.6

Anderson had earned his bonus by starring for the Elkton, Maryland, entry in the Susquehanna semipro league. He hit .442 and led the league in almost every offensive category, except stolen bases. He was tops in runs, RBIs, doubles, triples, and homers. Tom Lee, owner and manager of the Elkton club, suggested that Harry go to a local Phillies tryout, where he impressed Phils scout Cy Morgan enough that he eventually was offered the bonus. Reportedly the Phillies had to outbid several other clubs, including the Yankees, for Anderson’s services.7

Anderson got off to a slow start in the Phillies organization, in part because he continued his studies at West Chester, graduating in 1954 with a Bachelor of Science degree in physical education, and in part because he joined the Army right after the 1954 minor league season. By the time of his college graduation, he had two years of professional ball under his belt, first with the Class B Terre Haute Phillies in the Three-I League, then with Schenectady in the Class A Eastern League. He had plenty of success with Terre Haute, leading the team in hitting with a .323 average and socking 14 home runs. Promoted to Schenectady in the middle of the 1954 campaign, he struggled, hitting just .194 with 5 home runs in 183 at bats.

Anderson had little chance to play any baseball at all in 1955 and 1956 because he served on active duty in the Army. He told the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Allen Lewis, “In my two years in the Army, I played only about a month and a half of baseball — and that wasn’t very good caliber.”8 Released from the service in mid-1956, he managed to get into 88 games, again with Class A Schenectady, and while his power stroke was intact — he clubbed 13 round trippers — he struggled to make consistent contact at the plate, hitting just .235. Late in the season, Anderson found his batting stroke and led the Blue Jays to the Eastern League championship and batted .364 in the playoffs, showing the potential that the Phillies were hoping would blossom. During his first two years in the minors he had been a first baseman, but with an eye to future needs, the Phillies converted him to a left fielder on his return from the Army.

Despite his limited time in the minor leagues, his low batting average the previous year, and still being a work in progress in left field, Anderson found himself in the mix to be on the Phillies’ major league roster for 1957. Two things converged to make this happen. First, after a slow start, Anderson was hitting very well. He was the talk of spring ball with the long-distance home runs he was launching. Second, because of his Army service, under the military service rules then in effect in major league baseball, the Phillies could carry Anderson on the roster until June without having him count against the regular player roster limits.

On March 22 against the St. Louis Cardinals in St. Petersburg, Anderson accounted for all four of the Phillies’ runs with a three-run homer and a game-winning sacrifice fly. By the time camp broke, he was among the team leaders in RBIs and the power-starved Phils could hardly afford to keep him off the roster. While some felt that Anderson would benefit from more seasoning in Triple-A ball, the Phillies came north with him penciled in for platoon duty in the outfield.

His debut came in the second game of the season, popping out as a pinch hitter against the San Francisco Giants’ Rubén Gómez. His first start came in the second game of a doubleheader with the Giants at the Polo Grounds on April 21. Anderson introduced himself to the National League by driving in Ed Bouchee with a first-inning single; he then scored in front of a Stan Lopata triple. His deep fly ball in the second inning advanced Richie Ashburn to third base. He was hit by a pitch in the fourth inning and doubled in the sixth, scoring on a Jack Sanford infield single. Harry struck out in both the seventh and ninth. By the time he was pulled for defensive replacement Rip Repulski in the ninth inning, Anderson showed a box score line of 5 ABs, 2 R, 2H, 1 RBI, 1 HBP, and 2 Ks.

While playing part-time, splitting left field duties with Repulski, the firsts kept coming for Anderson. On April 22, he recorded his first outfield assist, cutting down the Dodgers’ Jim Gilliam at second base. His first pinch hit came on April 24 at Connie Mack Stadium off Pirates ace Bob Friend, a single that sparked a winning seven-run rally. His first home run came on May 3 at home off the Cubs’ Tom Pohalsky. This homer would be unique among the 60 lifetime dingers that Anderson hit; it was an inside-the-park blow to the farthest reaches of the spacious Connie Mack Stadium center field. To celebrate, Anderson also managed to chalk up his first-ever stolen base in the eighth inning off the battery of Turk Lown and Cal Neeman. The less-than-speedy Anderson registered just two more steals in the majors.

Early in Anderson’s major league career, colorful Phillies broadcaster Gene Kelly nicknamed him “Harry the Horse” for the Damon Runyon character made famous in the stage (1950) and movie (1955) musical Guys and Dolls. In the show, Harry the Horse is a wise-guy gambler and friend of the infamous Nathan Detroit. The character was played by tough-talking Sheldon Leonard both on Broadway and in the movie. Harry Anderson was no Runyon roughneck, though. Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Don Daniels described him as the “well-scrubbed…All-American boy type.”9 It is more likely the moniker described his physique, 6-foot-3 and 205 pounds. Anderson was certainly no racehorse on the base paths or in the outfield — but at any rate, the name stuck.

“The Horse” was able to break into a trot on June 18 when he smashed his first grand slam into the right field bleachers at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, providing veteran hurler Jim Hearn the margin he needed to record his 100th career victory. By the end of June, Anderson’s average had dropped to .219 as he struggled to adjust to major league pitching. During a July resurgence, however, he recorded five three-hit games and brought his average back to a respectable .262. Anderson also established himself as a solid left-handed power bat.

He ended his rookie campaign with a .268 average, 17 home runs, a .333 OBP, .453 SLG, and .735 OPS. This was all accomplished despite Connie Mack Stadium being an unfriendly venue for left-handed hitters. The right-field wall towered 32 feet in the air and turned back many a would-be homer. For his efforts, Anderson was named to the 1957 MLB Rookie All-Star team along with teammates Bouchee, Dick Farrell, and Jack Sanford, who was named Rookie of the Year. Anderson even received one tenth-place vote for MVP.

After that solid rookie campaign, the Phillies had high hopes for Anderson going into his sophomore season. Cincinnati Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts was one of Harry’s biggest fans, describing him as one of the best young left-handed hitters in the league, with “the finest pair of wrists I’ve seen on any hitter since Ted Williams.”10 Phils manager Mayo Smith felt that Anderson could “blossom into a real star.”11

First, however, there would be a position change. Bouchee, the Phils’ first baseman, would miss at least the first part of the 1958 season while getting mandatory counseling after being arrested on an indecent exposure charge at home in Seattle over the winter. Anderson had played first base through most of his minor-league career, so Smith was hopeful he could make the transition without an impact on his hitting. The experiment was short-lived. While he started 47 games there, his defense was shaky at best. As soon as Bouchee returned, Harry went back to left field permanently.

Whether or not the position change was the reason, he also got off to a slow start at the plate. His first homer of the season came on April 26 and the second did not come until May 16, at which point he was hitting just .247. From there, though, his offense took off. He ended 1958 as the premier left-handed run producer in the National League. Highlights over the next month included a three-hit game against Pittsburgh on May 18 that included a homer and three RBIs; a June 8 game against the Cardinals where he went 4-for-5 with two homers, a triple, and 3 RBIs in a losing cause, and four walks and a home run off Don Drysdale and the Dodgers on June 17.

On July 22, the Phils replaced Mayo Smith as manager with their former skipper: Eddie Sawyer, who had led the Whiz Kids of 1950. One of the first things Sawyer announced when he took over was that Anderson would play every day against right- and left-handed pitching.12 Anderson celebrated by hitting a game-winning three-run home run off Giant lefty Johnny Antonelli, to help Robin Roberts to a 3-2 win in Sawyer’s first game at the helm. On “Harry Anderson Night” at Connie Mack Stadium on July 31, a delegation from his hometown of North East, including his former coach Tom Lee, presented him with a silver tray and a check for $1,000. Harry celebrated by hitting his 15th home run of the season, a two-run shot to left in the first inning off the Cardinals’ Larry Jackson. On September 13, he had one of his finest days at the plate, going 5-for-5 with his final homer of the season.

The final line for Anderson’s 1958 season showed a .301 average, 23 home runs, 34 doubles, 97 RBI, .524 SLG, and .897 OPS. He also led the league with 95 strikeouts; the last player ever to lead a league in strikeouts with fewer than 100 in a full season. For his efforts, he was voted the Sophomore of the Year in the National League by the Baseball Writers’ Association. Reflecting on the award to the Inquirer’s Allen Lewis, Anderson said, “Well, that’s a nice honor to have, but I hope to keep on improving.”13 Another thing he hoped for the 1959 season was an end to being benched against left-handed pitching. In 1958, Anderson started 25 games against lefties, while being benched for 22 others. For the year he hit a solid .280 against them. As he told Lewis, “I know I can hit left-handers, if I get the chance.”14

Big things were expected from Anderson going into the 1959 season. His 1958 numbers were excellent, his attitude was first-rate, and if his defense was less than stellar, a permanent switch to left field would surely help him. Pre-season prognosticators like the Inquirer’s Lewis predicted that he could become one of the league’s “great sluggers.”15 The predictions were not to come true, however. After a decent start, Anderson suffered through a mediocre 1959 campaign in which his offensive output declined significantly in nearly every category. His batting average plummeted 61 points to .240, home runs were down from 23 to just 14, and RBIs were down from 97 to 63.

Contentious contract talks with new general manager John Quinn in the spring may have contributed to the decline. However, Eddie Sawyer felt that Anderson’s lack of seasoning in the minor leagues was his main trouble. A former teammate, Solly Hemus (by then manager of the Cardinals), thought Harry was just trying too hard. What the fans saw was that the line drives of 1958 had become the pop-ups of 1959. It also did not help that the Phillies were a bad team, a collection of aging Whiz Kids and younger players who failed to fulfill their initial promise. They finished dead last with a 64-90 record

For his part, Anderson took much of the responsibility for his performance on himself. He said that he felt that he was carrying too much weight and had gone to spring training overconfident after his strong 1958. Another problem he identified was the lack of a hitting coach. “I’m the kind of guy who needs supervision,” Anderson told Allen Lewis, whose columns also appeared in The Sporting News. “We didn’t have a batting instructor on the club last year and I didn’t get any help.” He was looking forward to working with the Phillies’ new hitting instructor, Hall of Famer Paul Waner.16

But as spring training opened in 1960, it was clear that Anderson was no longer considered a key component of the Philadelphia lineup. New outfield faces like Johnny Callison and Ken Walters were vying for playing time. Anderson played little in “A” games during spring training, but then, after Callison went into a late spring slump, he opened the season as the starting left fielder. He started the season hitting .417 over the first four games and smacking two home runs off the Braves’ Bob Buhl in an April 17 loss. After this initial success, Anderson tailed off precipitously and new manager Gene Mauch platooned him with Wally Post against left-handed pitchers. By the end of the month, he was hitting just .222. In May, he was relegated to just occasional use as a pinch hitter.

On June 15 Anderson was traded to the Cincinnati Reds along with Wally Post and minor-leaguer Fred Hopke for Tony González and Lee Walls. Cincinnati had long coveted Anderson, who had always hit well at Crosley Field, and Post was a very popular former Red returning to the nest. The move did nothing to awaken Anderson’s slumbering bat. In mid-July the Reds called up rookie first baseman Gordy Coleman, and Anderson went to the bench. From then to the end of the season he was used almost exclusively as a pinch hitter. Overall he hit only .167 with one home run in a mere 66 at bats (79 plate appearances) for the Reds.

On February 4, 1961, Anderson married Gail Porter at a ceremony at St. Andrews Episcopal Church in Wilmington, Delaware. The Sporting News reported that the new Mrs. Anderson was a member of The Models’ Guild of Philadelphia.17 The newlywed sent his signed contract into the Cincinnati front office from Miami, where he was honeymooning with his bride.18 While things were looking up on the home front, he reported to spring training knowing that he did not figure in the Reds’ long-range plans. On May 10 he was optioned to the Reds’ AAA affiliate in Indianapolis. In his final stint in the major leagues, Anderson pinch hit four times, singling on his last major league swing on May 5.

In the minors, Anderson hit just .227 with eight home runs in 100 games, splitting his time between Indianapolis and Jersey City. In 1962, he played for Cincinnati’s Pacific Coast League affiliate in San Diego, hitting .259 with 14 home runs in 115 games for the Padres. Then the 31-year-old Anderson retired from professional baseball and settled in Wilmington. He continued to play baseball with the Brooks Armored Car team, helping them win the Delaware Semi-Pro League championship.

Soon, though, Anderson turned in his baseball spikes for golf shoes. He had played golf in baseball players’ tournaments through the years and now had more time to devote to his game. Eventually he and his wife purchased a home right off the green to the fifth hole of the Wilmington Country Club’s North Course. He played in a number of local amateur tournaments and scored a hole-in-one in a member-guest tournament at the 136-yard second hole on his home course in 1975. The newspaper clipping reporting the achievement called him “Harry (The Horse) Anderson.” The nickname had stuck well past his playing days. Golf was a family affair for the Andersons. Harry’s wife, Gail, was an outstanding golfer; so were their two sons, Chris and Todd. Todd eventually went to Duke University on a golf scholarship. He was a two-time Academic All-American there and eventually played golf professionally.

In retirement, Harry worked as a manufacturer’s representative up and down the East Coast. In 1989, he was inducted into the West Chester University Sports Hall of Fame; in 1992, he became a member of the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame. At the Delaware induction ceremony, he told the crowd, “I played in an era that many people consider to be the best of all time in major league baseball. I played against Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, and Stan Musial. You play a whole career to reach certain goals. I played in semi-pro leagues, the minors, and eventually I was fortunate enough to stick in the major leagues.” 19

Why had Anderson flashed so brilliantly early in his career, only to fizzle out so quickly? It certainly was not lack of effort or poor attitude. Harry famously arrived early to spring training and was consistently described as a hard worker by his coaches. When he viewed his weight as a problem, he got into better shape. Perhaps it is as Eddie Sawyer suggested: Anderson’s limited minor league experience meant that he had a hard time adjusting when major league pitchers learned more about him and found ways to exploit his weaknesses. Perhaps it was his inability to lay off the high hard one, which often ended up in strikeouts or lazy pop-ups. It is also true that Anderson was never a strong fielder in the outfield or at first base. He was not a swift runner either. If he was going to stick in the majors, it was going to be as a power hitter who produced runs. When the power and production fell off, he found himself riding the bench and eventually being released.

Harry Anderson died unexpectedly of a heart attack on June 11, 1998. He was 66 years old. The day before, he and his son Todd had finished third in the Philadelphia region father-son golf tournament. Harry’s other son Chris told the Inquirer, “We’re all still in shock. He was a wonderful man. There weren’t many people who got to know him, who didn’t love him.”20 Anderson was buried at the Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery, New Castle County, Delaware.21

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Don Zminda.

Sources

In addition to the references below, the author also referenced Baseball-reference.com, SABR.org, and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Walter ‘Slim’ Anderson,” The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), June 7, 1976: 3,

2 “Delaware area obituaries,” The Morning News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), March 25, 1964: 11, This article covers the death of Blanche’s mother, Mrs. Helen Biddle.

3 Matt Zabitka, “Leatherwood Cited Cecil’s Top Player,” The News Journal, March 15, 1974: 21.

4 Zabitka, “Fans Remember ‘Horse’ Anderson,” The News Journal, April 11, 1991: 65.

5 “Fans Remember ‘Horse’ Anderson.”

6 Stan Baumgartner, “Anderson, West Chester (PA) Star, Signed by Phils for $40,000 Bonus,” The Sporting News. November 12, 1952: 17.

7 Baumgartner

8 Allen Lewis, “Anderson Hits Long Ball, Average Below Par, So Is Throwing Arm.” Philadelphia Inquirer. April 7, 1957: 66.

9 Don Daniels, “Phils’ ‘Hunting Guide’ for the Gals,” Philadelphia Inquirer. June 19, 1957: 39

10 Izzy Katzman,” Birdie Tabs Harry Anderson’s Wrists Second Only to Ted Williams,” The Sporting News. February 5, 1958: 20.

11 Allen Lewis, “Phil Lineup Overflows with Question Marks,” The Sporting News. April 9, !958:.4.

12 __________. Sawyer Anti-Platoon, Anderson Regular. Philadelphia Inquirer. July 23, 1958. 36.

13 “Writers Choose Anderson,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1958: 34

14 “Writers Choose Anderson.”

15 Allen Lewis. “No Power, Leaky Defense Hurt Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer. January 25, 1959: 76.

16 “Anderson to Be Prize Student of Waner at Camp,” The Sporting News. February 10. 1960: 27

17 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1961: 18.

18 “All 38 Reds Under Contract for ’61.” The Cincinnati Enquirer, February 12. 1961: 41.

19 Jack Ireland, New Inductees are a Mixture of Old and New. The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware). March 29, 1992. 1D

20 Jim DeStefano, “‘The Horse’ Dead at 66.” Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1998: 43.

21 Find A Grave. Retrieved from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/131703182/harry-walter-anderson. January 16, 2021.

Full Name

Harry Walter Anderson

Born

September 10, 1931 at North East, MD (USA)

Died

June 11, 1998 at Greenville, DE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.