Tony González

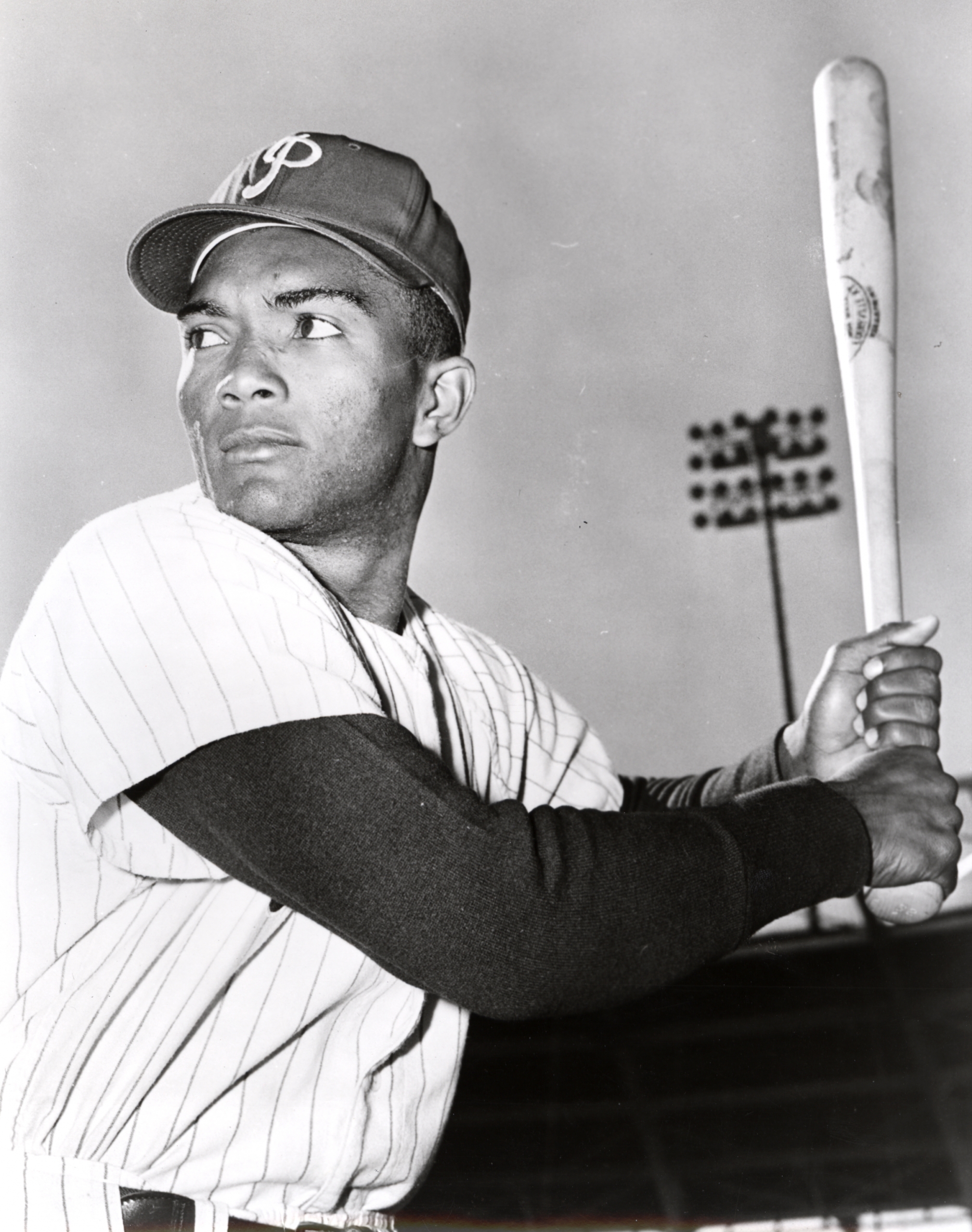

From 1960 to 1971, outfielder Tony González enjoyed a fine major-league career, He was never an All-Star – no insult, considering that Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Roberto Clemente were his peers – but he might have accomplished even more had he not suffered from back and eye problems. (The latter could have stemmed from a series of beanings.) The 5-foot-9, 170-pound Cuban remembered being called “Little Dynamite” because when he hit the ball, it was said to explode off his bat.1

From 1960 to 1971, outfielder Tony González enjoyed a fine major-league career, He was never an All-Star – no insult, considering that Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Roberto Clemente were his peers – but he might have accomplished even more had he not suffered from back and eye problems. (The latter could have stemmed from a series of beanings.) The 5-foot-9, 170-pound Cuban remembered being called “Little Dynamite” because when he hit the ball, it was said to explode off his bat.1

Gene Mauch, Tony’s skipper for nearly all of his eight-plus seasons with the Philadelphia Phillies, was a major proponent of platoons, and he often sat the lefty swinger against southpaws. That didn’t sit well with the proud player. Yet Mauch said that if Tony’s eyes had been healthy, he would have been one of the best-hitting center fielders “The Little General” had managed.2 Former major-league catcher and countryman Paulino Casanova thought González was the best natural hitter from Cuba he had seen.3

González was also a very good fly chaser – surehanded if not spectacular, with a strong arm. He appeared frequently in the corner outfield positions too, but he was the primary center fielder for five years with the Phillies – including the 1964 squad that colapsed down the stretch in the pennant race.

Andrés Antonio González4 was born on August 28, 1936, in Central Cunagua.5 A central, in Cuba’s bygone economic era, was a giant sugar-mill complex. Tony’s parents worked in this one, located in the province of Camagüey, in the eastern central part of Cuba, roughly 250 miles from the capital city of La Habana [Havana]. The mill strongly influenced González’s future as a pro. Central Cunagua had its own ballpark, which was probably the first exposure to the game for young Tony and for Bobby Maduro, a famous figure in Cuban baseball. Maduro’s father, a sugar planter, was a major Cunagua landholder. 6 Bobby Maduro’s friendship with Gabe Paul, a Cincinnati Reds executive in the 1950s, led to the formation of a pipeline between Cuba and the Reds chain. González was one of many talented prospects who came through this system. Along the way, he played for the Havana Sugar Kings, owned by Maduro, the top Cincinnati farm club from August 1954 to July 1960.

González attended Morón High School in the city of Ciego de Ávila. During sugar-cane season, which lasted from January to May, Tony helped his father to hoist 250-pound jute sacks of sugar. The hard labor enhanced his naturally athletic physique with great strength. During his career, “muscular” was a common theme in press descriptions. Noting the Cuban’s long arms, Reds manager Fred Hutchinson likened him to Charlie “King Kong” Keller, the former slugger with the New York Yankees. Catcher Dutch Dotterer, a Cincinnati teammate in 1960, said that after he grabbed one of González’s arms once, “it was like touching concrete.”7 Philadelphia teammate Clay Dalrymple observed, “Tony was the strongest guy from his fingertips to his forearms I ever met.”8

Young Tony’s love of baseball was so strong that his father’s discipline did not deter him from skipping work in the afternoon to play in an important game.9 As a teenager González began to climb the baseball ladder by playing for Central España, a sugar-mill team in the Pedro Betancourt Amateur Baseball League. This league was based in Matanzas province in western Cuba, far from his home. It was composed of young men like Tony who were hungry to advance the caliber of their game.

In 1971 González recalled his bonus when he signed with the Reds. “They gave me $10 and a bus ticket to Havana. Then they took it out of my first check.”10 Paul Miller, who was the business manager of the Sugar Kings, told the story from his side in 1959. After a Reds bird dog tipped Miller off in 1956, “I scouted him in three or four games and Tony sold me on himself in the first game I saw. He hit a home run off a southpaw and followed it with another homer off a right-hander.”11 A 2006 story shows the involvement of Paul Florence, then Cincinnati’s chief scout.12 In the team’s Cuban operation, Bobby Maduro and his staff worked with Florence to funnel prospects from the entire island to Havana.13

After touring Cuba with a team composed of players from Classes C and D, González reported to Cincinnati’s minor-league camp in Douglas, Georgia, in 1957. 14 He did not discuss his own personal experiences upon coming to the US for the first time, but the challenges that Latinos faced – language and culture, to start with – have been well documented. Those of African descent also had to contend with segregation in the Deep South, a jarring contrast with Cuba.15

Tony’s first US team was the Wausau Lumberjacks of the Northern League (Class C). He hit .342 in 14 games before he took sick. After he recovered he was assigned to the Hornell Redlegs in the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League, but he slipped, hurt his shoulder and missed another couple of weeks.16 Even so, in 86 games, González batted .275 with a league-leading 22 home runs.

In the winter of 1957-58, El Haitiano [The Haitian] – as González is known in his homeland17 – made his debut in the Cuban Winter League. His team, the Cienfuegos Elefantes, sported players from various big-league organizations, including Americans such as Brooks Robinson. Tony’s production was modest (.248 with a homer and five RBIs in 117 at-bats) – but in 1958 he made a huge jump all the way up to the Sugar Kings (Triple-A). For one thing, Bobby Maduro wanted to feature more local players.18 For another, it was a more comfortable environment for a Cuban. As Paul Miller explained, “We just couldn’t get American players because they were afraid to come to a revolution-riddled country. We had to use Cuban players and that was why we gave Tony his chance earlier than it might have come under normal conditions.”19

Regardless, González quickly became a regular in right field and held his own against Triple-A competition (.265-11-47 in 427 at-bats). One notable stat was that González was hit by pitches 13 times. This was something that happened to him frequently in the majors too – 71 times in his career. Of interest here is that according to his own description in 1964, Tony did not crowd the plate. In fact, he said that because he stood far back in the batter’s box, it gave the illusion that he was away from the plate.20

González returned to Cienfuegos for the 1958-1959 winter-league season. His average dipped to .235 in 170 at-bats, but by then he had established himself as the Elefantes’ regular center fielder and his job was not in jeopardy. Other notable teammates with the Elefantes during those years included Camilo Pascual and Pedro Ramos, then both starting pitchers for the Washington Senators.

In 1959 Bobby Maduro made changes to bolster the Sugar Kings’ sagging attendance (the Havana fans had grown disenchanted for various reasons, one being that the club had finished in last place in the International League the previous summer). He brought in highly regarded Preston Gómez as manager, and shortened the distances to the fences in Havana’s Gran Stadium, which had been the toughest International League Park in which to hit home runs. The friendlier confines helped Tony to hit five home runs in the first seven games and 20 for the season, second-best on the team. In his breakout season, as the center fielder, he batted a solid .300 with 81 RBIs in 149 games, led the league in triples with 16, and became the Kings’ MVP. Paul Miller said, “González loves baseball, and he improved defensively in center field. He is not distracted at the plate, or in the field, and he studies the pitchers. I think he has a great future in baseball.”21

The Kings finished in third place in the IL during the regular season, but won the Governor’s Cup by defeating second-place Columbus in four games and fourth-place Richmond in six games. González then gained broader attention with his excellent play in the 1959 Little World Series; he hit .320 in 25 at-bats. Havana beat the favored Minneapolis Millers, the previous year’s Triple-A champions, in a hard-fought, dramatic seven-game series. A cold snap in Minneapolis caused the last five games to take place in Havana, with the likes of Fidel Castro and Ché Guevara in attendance. When the Cuban club won, it sparked a huge national celebration.

González married Rosaura Feal Yeyes on November 15, 1959.22 He continued his hitting display in the 1959-1960 Cuban winter season. Playing again for Cienfuegos, he hit .310 to lead the league, with 10 homers and 35 RBIs. The Elefantes won the Cuban championship and thus went on to represent Cuba in the Caribbean World Series. The 1960 edition was the last for this tournament before it went on hiatus until 1970. Cuba swept Panama, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela in the double round-robin. González played in four of the six games and hit .429 [6-for-14]. Over half a century later, he remained particularly proud of this championship, which he felt was not widely publicized enough.23

González made the Cincinnati roster during spring training 1960 – despite a herniated disc in his back that hampered him.24 He made his major-league debut in the Reds’ home opener on April 12 against the Phillies. Tony led off the second inning with a single against Robin Roberts and hit a two-run homer off the future Hall of Famer in the fifth. Over the years, González handled Roberts better than he did any other pitcher.25 He claimed that his most difficult foe was Ted Abernathy, but the record shows that he fared reasonably well against the submariner.26

González got into 39 games with the Reds, playing right field and pinch-hitting. On June 15, 1960, Cincinnati traded him to the Phillies with infielder-outfielder Lee Walls for first baseman Fred Hopke and outfielders Harry Anderson and Wally Post. It was a typical deal for Phillies GM John Quinn: out with the old, in with the new. On the other side, Cincinnati had acknowledged that Tony was a prize prospect – but the Reds already had Vada Pinson, then 21 and seemingly a superstar to be, in center field. The following year, Frank Robinson also moved back from first base to the outfield.

The trade came a week after a ninth-inning González error helped turn a 1-0 lead into a 2-1 loss. It fell to much-respected Reds coach Regino “Reggie” Otero to deliver the news. Otero, a longtime Cuban baseball man, had taken Tony under his wing that spring, as he did with many other young Latino players. “If it was anybody else but Reggie,” González supposedly said, “I punch them in the mouth. I want to quit.” Otero convinced him not to.27

Tony’s new manager, Gene Mauch, had been the Minneapolis skipper during the 1959 Little World Series. He said, “We gave up a lot, but it was the kind of deal we had to make. González is young and I think he’s going to be an outstanding player in the near future.” He added, “I don’t like to use the word platoon, but I guess you’d have to say that’s what we plan to do with him for a while. … Let him come along slowly, have as good a year a possible this first season, and gradually work him into the lineup every day.”28

Over the years González respectfully took issue with Mauch’s platooning. There was logic to the idea, though – during his career Tony did far better against righties than lefties, except for the 1963 season.29 Harry “Peanuts” Lowrey, the first-base coach for Philadelphia between 1960 and 1966, worked with González to help his hitting and fielding techniques. Lowrey was a former major-league outfielder of Mexican descent on his mother’s side. At 5-feet-8 he was almost the same size as his pupil.

In Philadelphia González had the pleasure of playing behind two countrymen, second baseman Tony Taylor, whom the Phillies had acquired just over a month before, and big first baseman Panchón Herrera. Although John Quinn was known to be tight with a buck, he did bring in black and Latino talent for the Phillies.

González hit .299 for the Phillies over the rest of 1960, with 6 homers and 33 RBIs. Back in Cuba for the winter of 1960-1961, he played again for his beloved Cienfuegos team, which finished in first place. He said goodbye to the Cuban league by hitting .290 in 217 at-bats and leading the circuit in runs scored with 42. The Castro government abolished pro baseball in Cuba at the end of that season. Tony left Cuba like many other players, through Mexico.

In 1961, González’s first full year with the Phillies, he hit .277-12-58 in 126 games. That spring, Gene Mauch pulled him from an exhibition game and fined him $100, for what the skipper perceived to be loafing after a deep fly ball. He also questioned Tony’s hunger for the game. González told Mauch the reason – his back hurt – but the fine stood.30 The serious nature of the disc injury came to light later.

In the absence of Cuban pro ball, González went to Puerto Rico that winter. With the San Juan Senadores, he was a contender for the batting title. He finished third at .322, leading the league in runs scored and doubles. However, he was not eligible to play winter ball again until 1966-67, because of a mandate from Commissioner Ford Frick. This edict prevented Latino players from playing winter ball in countries other than their own – which had an especially profound impact on Cubans. Tony Taylor and González, to name just two players, “both chafed under the restrictions.”31 The policy was finally relaxed under Commissioner William Eckert, no doubt through the efforts of Bobby Maduro.32 González returned to San Juan and played with the Senadores once more in 1967-68. He hit over .300 in both seasons.

Coming off his 1961-62 performance with San Juan, González’s batting average zoomed to .302 during the 1962 summer season. He hit a career-high 20 homers with 63 RBIs in 118 games. Fifteen of those homers went to left field, prompting Clay Dalrymple to recall, “He could rip balls the opposite way.”33 Tony’s errorless season that year was also the first by an everyday big-league center fielder. His back problems brought González’s season to an end, however, after August 21. On September 10 he underwent surgery: a bone graft in his right sacroiliac joint.34 He was in a cast for several weeks but looked forward to resuming baseball activity by January.35

González was back in action by Opening Day 1963. He shared time in center field with Don Demeter and in left with Wes Covington. On June 23 his streak of errorless games ended at 205. On August 16 he was beaned by a pitch from Pittsburgh’s Joe Gibbon, a southpaw whose sweeping sidearm delivery was very tough on lefty batters. González had been hitting .329 at the time but then went into a slump. He finished the year at .306, with only 4 homers and 66 RBIs. Gene Mauch said that the dropoff in power came because NL pitchers were taking a different approach, but Tony differed. In 1964, he said, “I just wasn’t strong after my operation. … I feel weak so I just try to meet the ball, not swing too hard.”36

Shortly after the 1963 season, González played in the one and only Latin American players’ game. Held at the Polo Grounds in New York City on October 12, it was the last baseball game played at the old ballpark before it was demolished. Tony scored two runs for the NL’s Hispanic stars as they beat the AL’s, 5-2.

When the Phillies traded away Don Demeter in December 1963, the team acknowledged its need for a strong righty-hitting outfielder, though González had just come off his best season ever against lefties. Indeed, he earned a handful of MVP votes in 1963, as he would later do in 1967 and 1969 too. González was the incumbent center fielder for 1964. However, in the fourth game of the season, he was beaned again, this time by Chicago’s Bob Buhl. Tony remained conscious but was carried off the field on a stretcher, and held overnight at the hospital for observation.37 He missed just one game, thanks to a break in the schedule.

Soon thereafter, a special new batting helmet was constructed for him – the first in the big leagues with a premolded earflap. Other players had previously improvised earflaps, notably, the Minnesota Twins’ Earl Battey and Tony Oliva. It took until early June for the new headgear to arrive. When it did, González said, “That’s all right. Let those pitchers think I’m scared.” 38 The protection paid off: On August 11 González suffered yet another beaning, this one from Dick Ellsworth of the Cubs. The pitch crashed directly into the flap.39

González finished the 1964 season with a modest .278-4-40 batting line in 131 games. He battled through physical complaints: an eye inflammation that caused him to use medicated drops before each game, as well as a nagging groin injury.40 He was seldom able to run all-out that year. Gene Mauch later said, “Until the last three weeks of the season, I don’t think Tony’s leg felt 100 percent.” In retrospect, that could have been lingering side effects from his back operation.41 In 2012 González still fondly recalled the contributions that his fellow Cuban, Cookie Rojas, made during that season. Rojas, a former teammate with Cienfuegos, started 52 games in center that year when Tony was out of the lineup.

In 2012 González’s recollection of the ’64 “Phold” revealed a common, enduring sentiment: bewilderment at the many ways that the team found to lose. In particular, he still wondered about the game in which Chico Ruiz stole home. He sympathized with the frustration of the Boston Red Sox during their collapse in September 2011. Previously, he had expressed the same feelings for the 2007 New York Mets.42

From 1965 through 1968, González bounced between left field and center, with occasional appearances in right. He shared time with a mix of young talent (Dick Allen, Alex Johnson, John Briggs, Adolfo Phillips) and vets (Don Lock, Harvey Kuenn, and Jackie Brandt). In 1965 he commented about the effect of platooning. “When I sit on the bench for four or five days, I lose my timing (at bat) and some of my speed in the outfield.”43 Nonetheless, he had 13 homers in 108 games that year, his second-best single-season total. He noted that his eyes were not bothering him, saying, “I just decided to forget about it, to leave it up to God and see what happened.”44

González still wished he could be an everyday player. In 1967, he remarked, “It’s hard to stay loose. … When you face [lefties] only once in a while, you press up there.”45 That year, facing righties 80% of the time, he posted a career-high .339 batting average – second only to Roberto Clemente in the NL. “I’m loose,” he said, adding, “I’m not trying to go for the long ball. I always see the ball good all the time.”46

After the 1968 season, with 21-year-old Larry Hisle the heir apparent in center field, the Phillies left González unprotected in the October expansion draft. The San Diego Padres selected him with the 37th pick. He played in only 53 games with soft batting totals (.225-2-8), mostly in left field. The Padres traded him to the Atlanta Braves on June 13 for Walt Hriniak, a catcher who later became a well-known hitting coach; little-known infielder Van Kelly; and pitcher Andy Finlay (a former top draft pick in 1967 who never made it to the majors). The trade proved beneficial for the Braves. Over the rest of the ’69 season, González played in 89 games and hit .294-10-50 in 320 at-bats. He shared time in left field with Rico Carty and in center field with Felipe Alou, which allowed some rest for Hank Aaron. Tony was also good in the clubhouse. “Quick with a smile and quicker with a needle, Gonzalez is well liked by teammates,” an Atlanta sports scribe wrote.47

Atlanta won the National League West in the first year of divisional play. Although the New York Mets swept them en route to their World Series victory over Baltimore, González hit 357 (5-for-14) in his only chance at US postseason play. In the opener, his solo homer and double off Tom Seaver drove in two runs, though his costly eighth-inning error capped the Mets’ winning rally. It was an echo of 1964. In 1990, ahead of a Braves old-timer’s game, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote, “For Tony Gonzalez … the memory of 1969 still lingers hurtfully.” Tony himself said, “Things about that year still bother me a little bit. I still think about it. That year we really wanted to go all the way. We thought we could do it. But something happened. It’s a funny game.”48

Despite his very good second half with Atlanta in 1969, González did not play the entire 1970 season with the team. The Braves had traded Felipe Alou, but they still had a number of younger outfielders, including a strong reserve in Mike Lum and an excellent prospect in Ralph Garr. After González hit .265-7-55 in 123 games, his contract was sold to the California Angels on August 31. The Angels were then in second place in the AL West, just three games behind the Minnesota Twins, and they sought a capable veteran for the stretch drive. “Now we’ve strengthened our hand,” said GM Dick Walsh.49 Tony played in 26 games and hit .304-1-12 in 92 at-bats – but California faded and finished third.

During the 1971 season González played the most innings of any Angel in left field. Early in the season, he served mainly as a pinch-hitter, but he stepped in for his troubled former Phillies teammate, Alex Johnson. He also saw some action in center and right, hitting .245-3-38 in 111 games. He played his final major-league game that September 29 – the Angels released González on October 27. In the spring of 1972 he called it “the biggest surprise I’ve ever had.” He added, “I’m not ready to retire. … The only thing that can keep me from playing three or four more years is injury.” He was speaking from the training camp of the Montreal Expos – then managed by Gene Mauch – as a free-agent invitee. Tony said of Mauch, “I know what kind of manager he is. He knows what I can do.”50

González did not make the Expos roster, though he survived until the final cuts. In 12 major-league summers, he hit .286 with an on-base percentage of .350 and slugging percentage of .413 (fueled by 103 homers). He committed only 39 errors, for a .987 fielding percentage.

Tony was not yet done playing. He went to Mexico, joining the Jalisco Charros, based in Guadalajara. He hit .375 with two homers and 12 RBIs in 24 games. Starting in July he and fellow Cuban Zoilo Versalles then played for the Hiroshima Toyo Carp of the Japan Central League for two months. González batted .294-0-4 in 31 games.

At the age of 36 in 1973, González returned to the minors for the first time in 14 years. He rejoined the Phillies organization as a player-coach for their Double-A club in Reading, Pennsylvania. He hit .345 in 29 at-bats in 45 games during his last season as an active player. He remained as a coach for the R-Phils, working with hitters and outfielders, through 1976. He later worked in a similar capacity in the California Angels chain.

In 1985 the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile in Miami) inducted González. He kept in touch with baseball in his homeland. When the Baltimore Orioles played an exhibition game in Havana’s Gran Stadium in March 1999, Tony and Panchón Herrera were there, pulling for the Cuban squad. “Even though they didn’t win, they played them well,” González said.51

As late as the early 2000s, González participated in the Phillies’ Phantasy Camp; he was in good health and excellent shape.52 As of 2012, he lived in the Miami, Florida, area with Rosaura and their only child, a son. He stayed in good condition by taking daily power walks of five miles.

Tony González died on July 2, 2021 in the Miami suburb of Cutler Bay. He was 84. His passing did not receive attention in the press, even from Miami’s Spanish-language newspaper, El Nuevo Herald.

Last revised: April 19, 2023

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tony González and Paulino Casanova for their personal memories and assistance. José Ramírez also wishes to thank his son and fellow SABR member, José I. Ramírez, Jr., for assisting in checking facts and looking up information.

Sources

Interviews

Tony González, February 16, 2012.

Paulino Casanova, December 9, 2011.

Books

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2003).

Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003).

Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Miami: Review Printers, 1996).

Websites

baseball-almanac.com

retrosheet.org

www.japanbaseballdaily.com (Japanese statistics)

Notes

1 Telephone interview of Tony González by José Ramírez, February 16, 2012.

2 Telephone interview of Tony González by José Ramírez, February 16, 2012.

3 Telephone interview of Paulino Casanova by José Ramírez, December 9, 2011.

4 His mother’s maiden name was also González, meaning that his full Hispanic surname is González González.

5 The name of the mill was later changed to Bolivia Sugar Mill.

6 H.A. Granary, “Central Cunagua, the World’s Finest Sugar Estate,” The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer, June 7, 1919, 363. It does not appear that González and Maduro (who was 20 years older than Tony) ever talked to each other about the place where they grew up. Maduro’s privileged upbringing was much different. Indeed, after his father branched out from sugar into insurance and other holdings, the family was among Cuba’s wealthiest.

7 Earl Lawson, “Cuban Strong Boy No. 1 Red Picket Prize,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1960, 11.

8 Robert Gordon, Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 66.

9 Lawson, “Cuban Strong Boy No. 1 Red Picket Prize.”

10 Dick Miller, “Ex-Benchrider Gonzalez No. 1 Angel Swatsmith,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1971, 19.

11 Jimmy Burns, “Go-Go Gonzalez Winning Vivas with Sparkling Play,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1959, 41.

12 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 18, 2006.

13 According to a story on various Cuban websites, one day Cuco Pérez – a farm administrator for Bobby Maduro – came to a game to sign a player named “Conguito” Macías, but Macías fractured his ankle. The locals urged Pérez not to go away empty-handed but to sign González instead. In 2012 González said he knew of Macías – while adding that a lot had been written about him that one could not always believe.

14 Burns, “Go-Go Gonzalez Winning Vivas with Sparkling Play.”

15 For more on the subject, one in-depth reference is Samuel O. Regalado, ¡Viva Baseball! Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

16 Burns, “Go-Go Gonzalez Winning Vivas with Sparkling Play.”

17 El Haitiano is Spanish for The Haitian. González does not disclose the origins of his Cuban nickname, for reasons he prefers to keep private.

18 Maximo Sanchez, “Fans’ Club Helps Sugar Kings Top ’57 Gate Total by Early June,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1958, 13.

19 Burns, “Go-Go Gonzalez Winning Vivas with Sparkling Play.”

20 Allen Lewis, “Gonzalez Feels Strong as Bull; Sees HR Boost,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 19.

21 Burns, “Go-Go Gonzalez Winning Vivas with Sparkling Play.”

22 Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965 edition.

23 Telephone interview of Tony González by José Ramírez, February 16, 2012.

24 Allen Lewis, “Phils Looking for Remedy for Gonzalez’ Puny Hitting,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1965, 25.

25 10-for-13 (.769) with two doubles and two homers.

26 6-for-26 (.231). He was 0-for-13 against Jim Owens.

27 Ron Smith, “Big Brother to All the Latins,” Baseball Digest, August 1963, 68. Otero played 14 games with the Cubs in 1945 amid a long minor-league career. He managed the Havana Sugar Kings from 1954 to the middle of 1956. He remained in the Cincinnati organization while managing in Monterrey, Mexico (which had a working agreement with the Reds). He then served as a coach with the big club from 1959 to 1965, also acting as a liaison between Cuban players and management, helping players to understand cultural differences and what life was like in the States.

28 Allen Lewis, “Fading Favorites Dropped as Phils Give Jobs to Kids,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1960, 20.

29 For his career González batted .303 against righties, with a .366 on-base percentage and .442 slugging percentage. His respective percentages against lefties (whom he faced about 20 percent of the time) were .219, .288, and .299. In 1963, he hit over .300 against both righties and southpaws.

30 “Mauch Mixes Tough, Gentle Moods in Moulding Phillies,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1961, 8.

31 Allen Lewis, “No Idle Moments – Phils Find Variety of Off-Season Jobs,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1966, 26. See also Lawrence Baldassaro and Dick Johnson, The American Game: Baseball and Ethnicity (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 173-174. Regalado, ¡Viva Baseball!, 143. When the mandate was issued, it was no longer possible for Cubans to go back home, and even if they could have, their professional league had been abolished by the Castro regime. Pedro Ramos pointed out the injustice because Americans could get jobs during the winter in their hometowns. Cubans were forced to sit out part of the year with no means of income – much needed in those days – or a venue to maintain their baseball skills. This led to an international flap when Frick tried to prevent Dominican players and Cubans from playing exhibition games in Santo Domingo in early 1963. Rafael Bonnelly, interim president of the Dominican Republic, questioned why someone outside of Dominican territory could dictate policy to him.

32 In December 1965, shortly after he came on the job, Eckert hired Maduro to direct the Office of Inter-American Relations, established in Miami. Among other things, Maduro served as coordinator between the Latin American winter leagues and Organized Baseball. The hiring came after the 1965-66 winter-league seasons were already under way.

33 Gordon, Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies, 67.

34 “Doctors See Full Recovery for Gonzalez by Next Spring,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1962, 18.

35 Allen Lewis, “Phils Trumpet Glad News: Gonzalez on Mend After Surgery,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1962, 15.

36 Lewis, “Gonzalez Feels Strong as Bull; Sees HR Boost.”

37 “Buhl Blanks Phils, 7-0, On Three Hits,” United Press International, April 18, 1964.

38 Allen Lewis, “Gonzalez’ Bat Mark Plummets; Quakers’ Attack Losing Steam,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1964, 12. Paul Lukas, “There’s No Service Like Wire Service, Vol. 3,” Uni-Watch.com, February 2, 2010.

39 “Two Phil Outfielders Hurt,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1964, 27.

40 Lewis, “Gonzalez’ Bat Mark Plummets; Quakers’ Attack Losing Steam.” Lewis, “Phils Sniffing Pennant Pastry as Cookie Refuses to Crumble,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1964, 9.

41 Lewis, “Phils Looking for Remedy for Gonzalez’ Puny Hitting.”

42 Telephone interview of Tony González by José Ramírez, February 16, 2012. “For ’64 Phils: Been there, done that,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 2007, D-5.

43 Allen Lewis, “Gonzalez, Fined for No Hustle, Goes Wild at Bat,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1965, 8.

44 Allen Lewis, “Fainting Phillies Take Heart as Gonzalez’ Big Bat Blazes,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1965, 17.

45 Lewis, “Gonzalez’ Speedy Getaway No Joke to Phil Opponents.”

46 Allen Lewis, “Phillies’ Tony Torpedoes Old Role as Platoon Man,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1967, 13.

47 Wayne Minshew, “Flexible Flyhawks: Braves Can Choose From Flashy Four,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1969, 12.

48 “’69 Braves still wince remembering playoffs,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 23, 1990, F-6.

49 “Angels Look for a Lift from Tony,” Associated Press, September 2, 1970.

50 Ron Smith, “Gonzalez: New Start,” Palm Beach Post, March 21, 1972, D-1.

51 Geoffrey Mohan, “U.S., Cuba Play Ball,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), March 29, 1999, A7.

52 Gordon, Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies, 67.

Full Name

Andrés Antonio González González

Born

August 28, 1936 at Central Cunagua, Camagüey (Cuba)

Died

July 2, 2021 at Cutler Bay, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.