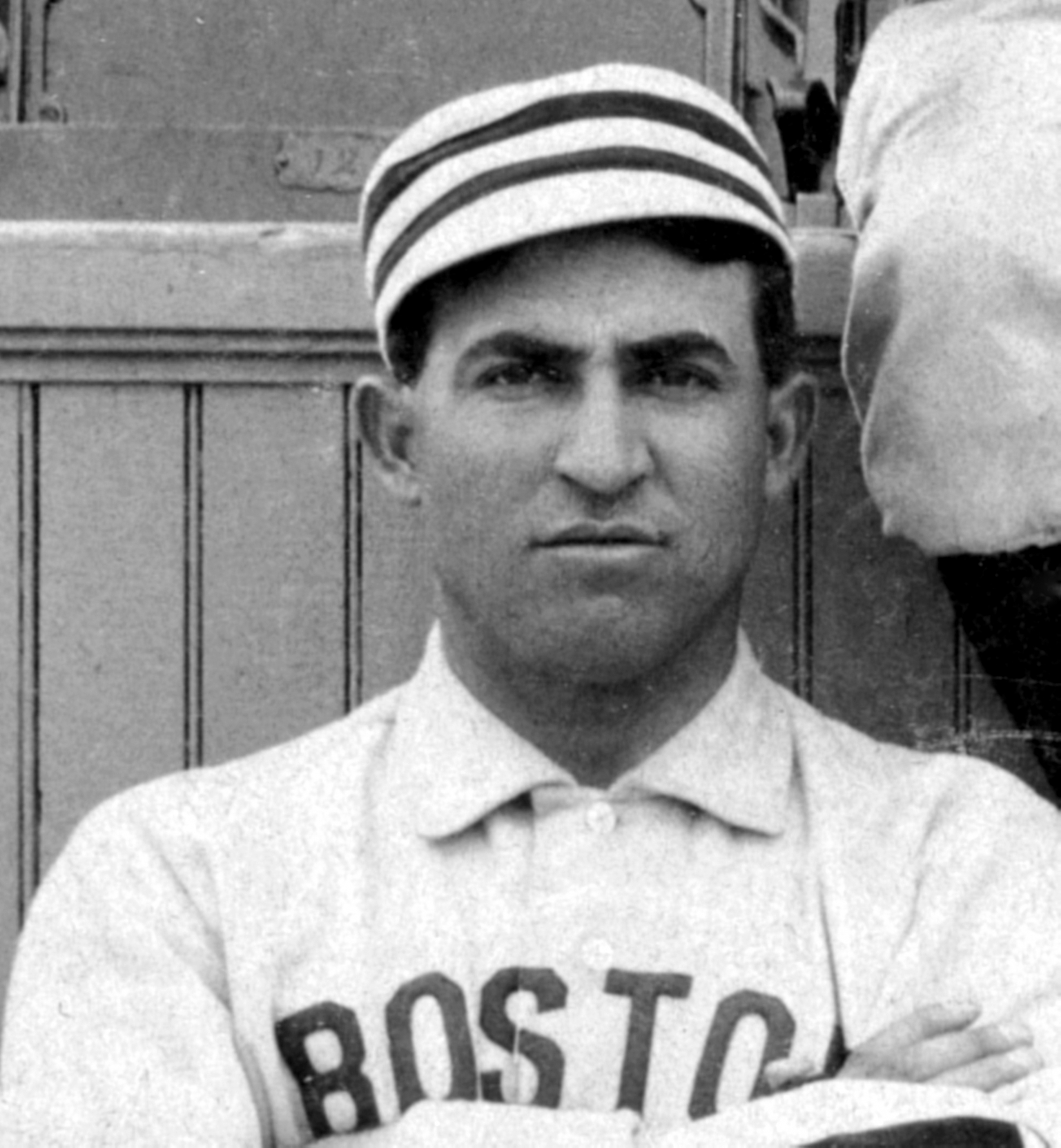

George Cuppy

Because of his dark complexion, he was called Nig.1 For the same reason, some sportswriters referred to him as the Cuban Warrior or the Cuban Hero. But Nig Cuppy was not African-American or Cuban. He was a first-generation American, son of immigrants from Bavaria.

Because of his dark complexion, he was called Nig.1 For the same reason, some sportswriters referred to him as the Cuban Warrior or the Cuban Hero. But Nig Cuppy was not African-American or Cuban. He was a first-generation American, son of immigrants from Bavaria.

George Maceo Koppe was born on July 3, 1869, in Logansport, Indiana, fourth of the eight children of Christina Stieffenheffer Koppe and Christian Koppe. Christina came to the United States in 1845. Christian immigrated five years later. The couple married in 1856. In 1880 the family, including 11-year-old George, was living in Eaton, Ohio, where Christian worked as a brick and stone mason. Later they returned to Indiana. Christian and Christina were living apart in Jasper County in 1900. By this time George was no longer living at home. After playing baseball for independent clubs in Indiana, George started his career in Organized Baseball at the age of 20 with the Dayton (Ohio) Reds of the Tri-State League in 1890. His baseball name became Cuppy, the phonetic spelling of the German name Koppe. It is not clear when he acquired the nickname Nig. In 1891 Cuppy divided his time between two clubs in the New York-Pennsylvania League, Jamestown, New York, and Meadville, Pennsylvania. The right-handed pitcher won 21 games that season and found time to play 17 games in the outfield.

On April 16, 1892, the 22-year-old Cuppy made his major-league debut with the National League Cleveland Spiders. His first major-league win came in his first start, on April 23. He bested Cincinnati Reds starter Billy Rhines, who was knocked out of the box in the first inning. Cuppy allowed five earned runs on eight hits and six walks with a wild pitch as his mates beat Cincinnati 14-5 at League Park. The 5-foot-7, 160-pound hurler had an outstanding rookie season, winning 28 games against 13 losses and posting an earned-run average of 2.51, fourth in the league. He was second on the team in wins, an accomplishment that happened many times. For each of his first five seasons, Cuppy ranked second in wins among Cleveland pitchers, always behind future Hall of Famer Cy Young. During those five years, 1892-1896, Cuppy and Young combined for 279 wins, the most of any two teammates in the majors over that span. In 1894 Cuppy led the National League in shutouts. A good-hitting pitcher, he scored five runs in an 18-6 win over the Chicago Colts on August 9, 1895. Cuppy pitched a complete game in that contest, one of the 224 times in his career that he finished what he started.

Cuppy was known as a slow pitcher, not only for the number of off-speed pitches he threw, but also because of the time he took between deliveries, which many hitters found frustrating. Newspapers of the day took delight in describing Cuppy’s actions in the pitcher’s box. One reporter wrote, “It is really amusing to those in the stands to witness the maneuvers of this little twirler with the swarthy complexion and pearly teeth. He fondles the ball, rubs it on the back of his neck, grins at the batsman, and then stops to adjust his cap and hitch up his trousers. He does all this several more times before he delivers the ball to the batsman.”2

In addition to his slow pitch, Cuppy also threw a jump ball, that is, a rising fastball. The elimination of the pitcher’s box and lengthening of the distance to the plate in 1893 may have been at least partly responsible for a decline in his performance during the 1893 season, but he recovered in 1894.

According to the Cleveland Press, one day in 1894 Cuppy announced that he was going to spring a surprise on fans and players alike at that afternoon’s game. When the game began Cuppy walked out into the pitcher’s box wearing a glove on his left hand. Other fielders had worn gloves before, but this was believed to be the first time in history that a pitcher had used a glove. By the end of the season use of the glove had been adopted by other pitchers.3

During his first six seasons in the majors, Cuppy had five 20-win seasons. (He collected 17 victories in the exception, his “poor” 1893 season.) In 1897 his arm gave out. He won only ten games that season and never came close to 20 again. During Cuppy’s tenure with Cleveland, the club consistently finished in the first division, including three seasons in second place, but they captured no pennants.

On March 29, 1899, Cuppy was transferred to the St. Louis club. (The St. Louis Browns were expelled from the league before the start of the 1899 season. The Robison brothers, who owned the Spiders, were allowed the St. Louis franchise without having to relinquish the Spiders. They took the best players from the 1898 Browns and Spiders and made an “A” team which stayed in St. Louis. The “B” team went to Cleveland, which went 20-134, drawing fewer than 10,000 fans for the season.) After playing second fiddle to Cy Young for so many years, was Cuppy now freed from comparisons with his more famous teammate? No. Young also joined St. Louis that season. However, Cuppy was sold to the Boston Beaneaters on May 23, 1900, and did not appear in a game for St. Louis that season. For the only time in his major-league career, Cuppy did not pitch on the same team as Young. With an 8-4 record, Cuppy won twice as many games as he lost that year, but he was far from the pitcher he had been in his heyday.

In 1901 as the American League gained major-league status, Cuppy joined a host of National Leaguers jumping to the new circuit. Among the jumpers was Cy Young. Both pitchers joined the Boston Americans. Cuppy and Young were teammates for one last time. This time Cuppy did not play second fiddle to Young; he was much further behind the maestro, ranking fourth in wins among the Boston pitchers with only four victories compared with Young’s 33. Cuppy’s four wins were outnumbered by his six losses, giving him the only losing season of his career.

The Americans’ manager, Jimmy Collins, made an effort to speed up the pitcher’s notoriously slow delivery. With the hyperbole that permeated sportswriting in that era, a reporter for a Cleveland newspaper wrote:

“Collins has served notice on Pitcher Cuppy that one and one-half minutes is the limit of time which will be allowed him in delivering the ball. Cuppy in the national league was noted as the living picture twirler. He assumed seventy-seven imposing and statuesque poses while in the act of delivering the ball, the poses melting into one another ’til the whole performance was like watching a kinetoscope picture with the machine slowed down. The bleachers used to take delight in rising and counting in unison from the time Cuppy received the ball through all the convolutions in his frame and the divers and sundry positions he assumes until with an Ajax-defying-the-lightning attitude he finally lets the ball go. … Collins has given one of his young players the task of standing behind Cuppy as he warms up in practice. The youngster is armed with a long hatpin and at the count of eight if the ball isn’t delivered, Cuppy receives a jab.” 4

Whether the manager’s efforts speeded Cuppy’s delivery is unknown. What is known is that it did not improve his effectiveness. During the season he was released, and his career on the big stage was over. Cuppy made his final major-league appearance on August 7, 1901, at the age of 32. His finale was a 10-4 loss to Joe McGinnity of the Orioles at Baltimore. A Logansport newspaper reported that Cuppy retained counsel in preparation of a lawsuit against the Americans for salary allegedly owed him. At the request of the club he went to Boston to enter negotiations on the matter.5 The outcome of the negotiations was not reported.

Cuppy was noted for his bubbling good nature and his fondness for harmless practical jokes. Once he announced he was going to build a 22-story hotel in Logansport. It would be so luxurious that it would make the famed Palace Hotel in San Francisco look like a wrecked shanty on the Wabash. The absurdity of locating such a building in a small Indiana town did not register with the public. Cuppy received more than 100 letters in his mailbox. There were applications for positions as manager, clerk, cashier, and bellboy; inquiries from builders, architects, and dealers in hotel furnishings. Cuppy answered every letter. This was to be a $10,000,000 project he said. He was going to pay himself one million as manager. None of the job applicants was good enough; none of the drawings submitted by builders or architects was satisfactory; the furnishings were not elegant enough.6

After leaving the majors, Cuppy returned to Indiana, where he pitched for and managed an Elkhart semipro club in 1902. For some time he and his former catcher Lou Criger ran a billiard parlor, appropriately called The Battery. Later he entered the retail tobacco business. The 1910 census showed George Cuppy, the owner of a cigar store, living in Elkhart. Cuppy was an excellent trapshooter, who scored well in tournaments.7

Cuppy died of Bright’s disease on his farm near Elkhart on July 27, 1922, at 53. He was buried at Rice Cemetery in Elkhart.

George “Nig” Cuppy was only a minor contributor to the Boston Americans in 1901. Unfortunately for him, he was released before the end of the season and was no longer around when Boston won the World Series in 1903. He never got to celebrate a league championship. However, he had posted 162 major-league victories against just 98 losses, which is certainly worthy of celebration.

This biography can be found in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin. To order the book, click here.

Acknowledgements

The kindness of Trey Strecker in sharing information about Cuppy’s life and career is deeply appreciated.

Sources

Cuppy’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Rich Eldred, “George Joseph Cuppy,” in Baseball’s First Stars, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds. (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 46.

David Nemec. Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, vol. 1. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 40-41.

Notes

1 Such a derogatory nickname would be unacceptable today, but nicknames based on physical characteristics were common in the early 20th century. Native Americans were routinely called “Chief”; deaf players were “Dummy.” Some of the better known examples include: Chief Bender, Three-Finger Brown, Nig Clarke, Fats Fothergill, and Dummy Hoy.

2 Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, August 8, 1900.

3 Cleveland Press, November 17, 1906.

4 Cleveland Press, June 19, 1901.

5 Cleveland Press, September 14, 1901.

6 Logansport Daily Reporter, September 14, 1908.

7 New York Times, April 28, 1919.

Full Name

George Joseph Cuppy

Born

July 3, 1869 at Logansport, IN (USA)

Died

July 26, 1922 at Elkhart, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.