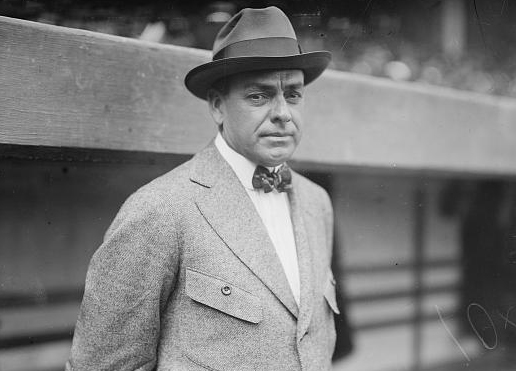

George Stallings

A dignified, fastidious Southerner who managed in street clothes and nervously slid up and down the bench so much that he frequently wore out his trousers, George Stallings compiled an 879-898 record and won only one pennant in 13 seasons as a major-league manager, yet that single gonfalon was enough to ensure his undying fame as “The Miracle Man.” Indeed, the amazing ascension of his Boston Braves to the 1914 National League flag, followed by their sweep of Connie Mack‘s heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series, still may be the most unlikely triumph in baseball history. The captain of those 1914 Braves, Johnny Evers, wrote that Stallings “will crab and rave on the bench with any of them,” yet he also wrote that “Mr. Stallings knows more base ball than any man with whom I have ever come in contact during my connection with the game.” He was, wrote Harvey T. Woodruff in the Chicago Tribune, “a pitiless and abusive critic while the game is on. When the game is over, he is mingling with his players, among whom he is immensely popular, laughing and jollying them in preparation for the morrow.”1

A dignified, fastidious Southerner who managed in street clothes and nervously slid up and down the bench so much that he frequently wore out his trousers, George Stallings compiled an 879-898 record and won only one pennant in 13 seasons as a major-league manager, yet that single gonfalon was enough to ensure his undying fame as “The Miracle Man.” Indeed, the amazing ascension of his Boston Braves to the 1914 National League flag, followed by their sweep of Connie Mack‘s heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series, still may be the most unlikely triumph in baseball history. The captain of those 1914 Braves, Johnny Evers, wrote that Stallings “will crab and rave on the bench with any of them,” yet he also wrote that “Mr. Stallings knows more base ball than any man with whom I have ever come in contact during my connection with the game.” He was, wrote Harvey T. Woodruff in the Chicago Tribune, “a pitiless and abusive critic while the game is on. When the game is over, he is mingling with his players, among whom he is immensely popular, laughing and jollying them in preparation for the morrow.”1

The son of William Henry and Elizabeth Virginia (Atwell) Stallings, George Tweedy Stallings was born in Augusta, Georgia, on November 17, 1867 (not on November 10, 1869, as his tombstone says). William Stallings was rather prosperous; the 1870 shows him with real estate valued at the time of $12,000. He served as county treasurer for Richmond County at the time. Ten years later, he was listed as a contractor. He and his wife had five children – all boys – and a servant (a butler) named Sam Jones.

George, the fourth-born of the five Stallings sons, attended Richmond Academy, and it is often reported that he graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1886 and attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Baltimore. His name doesn’t appear on VMI alumni rolls, however, and it is also doubtful that he actually attended medical school. Stallings married Bell White on April 2, 1889, in Jones County, Georgia. They had two sons before Bell divorced him in 1906. Stallings later married Bertha Thorp Sharpe, the widow of major leaguer Bud Sharpe, with whom he had one son.

If Stallings’ reputation depended solely on his playing career, no one would remember him. He made his big-league debut with the NL champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms in 1890, appearing in four games and going hitless in 11 at-bats before receiving his release. Stallings also appeared in three games while managing the Phillies in 1897 and 1898. His entire major-league playing career consisted of two hits in 20 at-bats. Stallings had more success in the minors — an 1897 publication claimed that he “was probably a member of more champion clubs than any other player of the present day.” The Phillies discovered him in 1886 while he was catching for an amateur team in Jacksonville, Florida. In need of seasoning, Stallings spent the next four years bouncing around the minors. After his short stint with Brooklyn, he switched to the outfield in 1891 “to give the [San Jose] team the benefit of his speed in the game every day,” and in fact he led the California League in stolen bases that year.2

Stallings’ managerial career began in 1893 when he managed his hometown team, Augusta of the Southern League. During the off-season he also served as the first baseball coach at Mercer College in Macon, Georgia, where he was succeeded in 1897 by Cy Young. In 1894 Stallings split the season between Kansas City of the Western League and Nashville, and the following year he managed Nashville to a Southern League pennant. After guiding Detroit of the Western League to fourth place in 1896, he was tapped to take over the Phillies. Stallings’ first tenure as a major-league manager gave no hint of future success. The Phillies lurched to a 55-77 record in 1897, finishing tenth in the 12-team NL. In 1898 they got off to an even poorer start (19-27), and Stallings was fired in mid-June.

George returned to the helm in Detroit in 1899 and was still managing there in 1901, after the Western League had renamed itself the American League and declared itself a major league. The Tigers finished that first big-league season third, with a 74-61 record, but Stallings ran afoul of AL president Ban Johnson, who claimed that the manager had tried to sabotage the new circuit by selling the Tigers to NL interests. Stallings later insisted that he couldn’t have sold the Tigers even if he’d wanted to, because Johnson himself owned 51 percent of the club’s stock. Nevertheless, he didn’t return to Detroit. Stallings managed Buffalo of the International League from 1902 through 1906, and Newark in 1908. (He was out of baseball in 1907, tending to the peach crops and cattle he raised on his plantation, the Meadows, in Haddock, Georgia, just outside Macon.)

In 1909 Frank Farrell asked Stallings to take over his troubled New York Highlanders, who had staggered home dead last during a dissension-torn 1908 season. Under Stallings the Highlanders improved to 74-77 in 1909. They were playing even better in September 1910 when Highlanders star Hal Chase, with an assist from Ban Johnson, convinced Farrell to fire Stallings and install Chase as manager. The club was 78-59 (.569) at the time. The Highlanders won ten of their last 14 games under Chase to finish second, but they fell back to sixth in 1911 and Chase was relieved of command.

Stallings spent 1911 and 1912 back in Buffalo before James Gaffney summoned him to replace Johnny Kling as skipper in Boston. George took over the bedraggled Braves after the team had posted four straight last-place finishes. His first glimpse of his new charges wasn’t encouraging: “I have never seen any club in the big leagues look quite so bad,” he later recalled. Managing the 1913 Braves, which led the NL with 273 errors, must have been a trying experience for a man who “could fly into a schizophrenic rage at the drop of a pop fly,” yet the team won 17 more games than it had in 1912 and rose to fifth place.3

No one expected the Braves to finish in the first division in 1914. Sure enough, Boston was in last place on July 15, though only 11½ games behind the league-leading Giants. From that point on, however, the Braves proceeded to win 52 of their last 66 games and finished the season with a 94-59 record, 10½ games ahead of New York. Stallings was profoundly superstitious — if his team mounted a rally he would freeze in position until the rally ended — and it’s fun to imagine what his antics must have been like during the Braves’ incredible run. Once, or so the story goes, he happened to be leaning over to pick up a pebble when the Braves started a rally; after it was over, he was so stiff he had to be helped off the field. Stallings also abhorred peanut shells and pieces of paper on the field, much to the delight of mischievous opponents.

Certainly the stalwart pitching of Bill James, Dick Rudolph, and Lefty Tyler, and the solid play of the veteran Evers and young Rabbit Maranville, had more to do with accomplishing the “miracle” than the 46-year-old manager’s silly superstitions, but many of his players freely attributed their success to his guidance. Stallings is credited with pioneering the use of platoons to maximize the Braves’ feeble offense (only one regular topped .300, and no Boston outfielder accumulated even 400 at-bats), but his ability to persuade his players that they were winners was probably more important than his strategic decisions.

Following the remarkable 1914 season, Stallings managed the Braves to second place in 1915 and third in 1916. Beginning in 1917, however, the team finished in sixth or seventh for each of the next four seasons, and their record got worse each year. Stallings resigned after the 1920 season. He guided Rochester of the International League from 1921 until he resigned in July 1927.

Stallings signed on to manage the Montreal Royals in 1928 but spent much of the year hospitalized for heart disease in Macon and Atlanta. When a doctor asked him if he knew why his heart was so bad, he supposedly replied, “Bases on balls, you son of a bitch, bases on balls.”4 George Stallings died at home in Haddock, Georgia, on May 13, 1929, and is buried in Macon’s Riverside Cemetery.

A version of this biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Potomac Books, 2004), edited by Tom Simon. It is also included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to David Fleitz.

Sources

Alexander, Charles C. John McGraw (New York: Viking, 1988).

Brandt, William E. “The Breaks,” Saturday Evening Post, July 19, 1930.

Evans, Billy. “The Baseball Hero of 1915?” Harper’s Weekly, March 6, 1915.

Evans, Billy. “The Braves in War Paint.” Harper’s Weekly, September 5, 1914.

Frommer, Harvey. Baseball’s Greatest Managers (New York: Franklin Watts, 1985).

James, Bill. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Villard, 1986).

Kohout, Martin. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2001).

Lieb, Fred. Baseball As I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1977).

Lieb, Frederick G. Connie Mack: Grand Old Man of Baseball (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

Maranville, Walter “Rabbit”. Run, Rabbit, Run: The Hilarious and Mostly True Tales of Rabbit Maranville. (Society for American Baseball Research, 1991). Reprinted 2012.

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: Vintage, 1985).

Schoor, Gene. The History of the World Series: The Complete Chronology of America’s Greatest Sports Tradition (New York: William Morrow, 1960).

Stallings, George T. “The Miracle Man’s Own Story,” Collier’s. November 28, 1914.

Notes

1 Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1914.

2 Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1914.

3 Tom Meany, “The Miracle Man,” Baseball Digest, July 1949, 71. This article was an excerpt from Meany’s book, Baseball’s Greatest Teams (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1949).

4 Jonathan Weeks, Baseball’s Most Notorious Personalities: A Gallery of Rogues (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2013), 113.

Full Name

George Tweedy Stallings

Born

November 17, 1867 at Augusta, GA (USA)

Died

May 13, 1929 at Haddock, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.