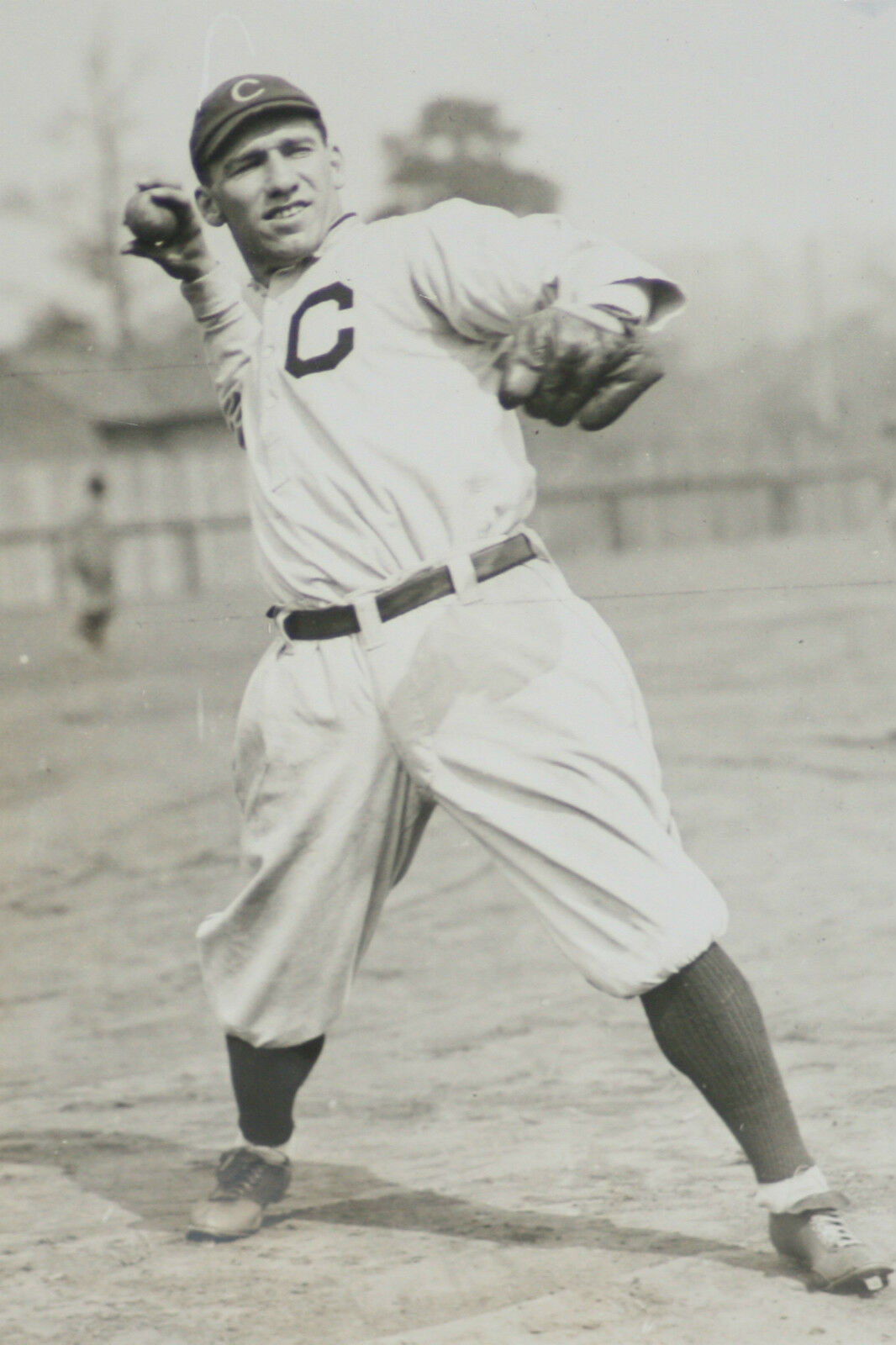

George Yantz

George Webb Yantz was a bricklayer, journeyman catcher, and tough negotiator who reached the major leagues for one game and retired with a 1.000 career batting average.

George Webb Yantz was a bricklayer, journeyman catcher, and tough negotiator who reached the major leagues for one game and retired with a 1.000 career batting average.

Yantz was born on July 27, 1886, in Louisville, Kentucky, the second oldest of five children born to Josephine and Charles Yantz. Charles worked as a bricklayer and contractor, while Josephine was a homemaker. The year before George began his professional baseball career, his older brother, William, was killed when he fell 40 feet while working at the Schaefer-Meyer Brewing Company’s building in 1906.1

By the time he was 21, George Yantz had established himself as one of the top ballplayers in Louisville. He starred for the Fetters amateur team in 1907, winning a Best Batter gold medal at a postseason banquet honoring 44 local players.2

He made his professional debut with the Class-B Grand Rapids Wolverines in 1907. It was a local connection that sent Yantz to Grand Rapids; Louisville native Phil Arnold owned the Wolverines and knew of Yantz. After a month with Grand Rapids, Yantz returned to Louisville and played for the Fetters team.

Yantz broke a finger in an indoor game on March 6, 1908. The Fetters and the Sutcliffes, another local amateur team, played in Louisville’s armory in front of a “small but enthusiastic” crowd.3 Yantz was playing first base when he broke his pinky finger and had to leave the contest. His finger healed in time for the 1908 regular season.

Yantz stayed close to home in the Kentucky-based Blue Grass League over the next two seasons. He suited up for Lawrenceburg in 1908 and hit what is believed to be the first home run of his professional career on August 13 of that year against the Frankfort Statesmen. On May 5, 1909, Yantz married Eleanor Grass in Louisville and then played in a game two days later. He also made a second commitment, this one less permanent than marriage, signing a nonreserve contract with Frankfort.

Or at least Yantz thought it was a nonreserve contract when he signed to play for the Texas League’s San Antonio Bronchos in 1910.4 Officials of the Frankfort team had other ideas, claiming they still held Yantz’s rights. The Louisville Courier-Journal wrote that “Yantz has never been released by Frankfort and will not be, it is believed, without a substantial consideration. He was one of the very best catchers in the Bluegrass (League) last season and is a valuable man in any place. It is said that he claims he understood the agreement between him and the Frankfort team was that he was to have his release at the end of the season, but no one was given authority to make any such agreement.”5

All parties must have come to a resolution, because Yantz packed up and left for San Antonio in 1910. While reporting on the local guy Yantz’s departure, the Courier-Journal said he “is expected to make good,” calling him “a youngster” with a “promising future” and describing him as “a tireless worker, a fine thrower and a good hitter.”6

Most of Yantz’s defensive career was spent behind the plate, but he occasionally lined up as an infielder or outfielder, leading one reporter to say of Yantz: “Probably no backstop ever plugged an infield hole with more zeal or brilliance than the Texas Leaguer.”7 He brought that zeal for versatility to San Antonio in 1910 and used it in a 23-inning 1-1 tie against Waco on July 5.

Yantz started in right field that day and batted ninth, going 2-for-7 with a double. (It’s not often a team’s ninth batter gets seven at-bats.) Yantz probably felt sympathy for his teammate Louis Schan, who caught all 23 innings in San Antonio’s summer heat. The 23-inning marathon set the record for the longest game in Texas League history, a record that stood until San Antonio and Rio Grande Valley played 24 innings 50 years later on April 29, 1960.8

In 1911 Yantz joined the Southern Association’s Birmingham Barons and appeared in 121 of the club’s 138 games. A memorable day from that season came when Yantz was served with nine police warrants (one per inning) for playing on a Sunday in Nashville, where Sunday baseball was banned. The Barons’ president and manager had to pay fines, while the players were all found innocent in court the next day.9

The Barons invited Yantz back for the following year but the 1911-1912 offseason brought him more contract chaos. Yantz held out for more money, refusing to report to the team unless it agreed to pay him an extra $100 per month.10 The Barons were offering an extra $25 per month, but that didn’t cut it for Yantz.11 The 1912 season was approaching but Yantz was holding his ground and telling anyone who would listen that he was ready to work on a farm instead of reporting to Birmingham.

Finally, in late March 1912, Yantz ended his personal strike, leading the Birmingham News to exclaim, “George Yantz, the hold-out Baron backstop, has reported!”12 It’s unclear if his financial demands were met. When Yantz arrived, Birmingham manager Carlton Molesworth felt that the Yantz “salary thing is settled”13 and he didn’t elaborate to the press. It was neither the first nor the last time George Yantz was part of a transaction with twists and turns.

It proved to be a good career choice when Yantz picked baseball over farming in 1912. He excelled for the Barons that year, batting 20 points higher than the previous season while continuing his robust defense behind the plate, helping Birmingham win the Southern Association title and earning him serious consideration from major-league teams.

September 1912 was a transitory month for Yantz. First he was drafted by the St. Louis Browns in mid-September,14 but he never played a game for the team. The draft rules in those days allowed major-league teams to return minor leaguers within five days after drafting them,15 and that’s what the Browns did with Yantz, citing an excess of new talent as their reason.16

The Chicago Cubs had also “put in a bid for” Yantz and were able to scoop him up as soon as the Browns cut him loose.17 The Cubs originally drafted Lena Blackburne from the American Association’s Milwaukee Brewers, but Cubs owner Charles Murphy became concerned that Blackburne had an injured leg, so he surrendered Blackburne back to Milwaukee, opening up space on the Cubs’ depth chart for Yantz.18 The Cubs immediately added Yantz to their major-league roster and his first and only major-league stint was underway.

It was partly because of another player’s injury that Yantz was acquired by the Cubs and it was another player’s injury that got Yantz into his lone major-league game. Cubs starting catcher Jimmy Archer played the first seven innings on September 30, 1912, in the last week of the season, before a foul tip to his knee forced him out of the game. Acting manager Joe Tinker summoned Yantz from the bench to catch the final two innings against Pittsburgh, receiving the pitches of reliever Bill Powell in both frames.19

Sportswriters took notice of the height disparity between the 6-foot-2 Powell and the 5-foot-6 Yantz. “They immediately acquired the soubriquet ‘the long and short battery,’ for Powell belong [sic] to the tall and rangy class, while Yantz is as short as his name, and just as full of pepper as it sounds,” the Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times quipped.20 Yantz was listed at 168 pounds, and batted and threw right-handed.

Yantz’s two-inning visit to the majors included one at-bat. He stepped into the batter’s box against Pirates righty Claude Hendrix on a dry day in Chicago with temperatures in the 60s21 and struck a single. Or was it a double? Baseball stories can get distorted as years pass by, and the story of Yantz’s base hit certainly was. Obituaries decades later stated that Yantz “hit a double off the Pirate pitcher in his only batting appearance,” but all reliable box scores list his hit as a single.22 The Cubs lost the game, 9-3.

Had it not been for Archer’s knee injury, George Yantz might not have ever entered a major-league box score. His name wouldn’t have been immortalized in baseball encyclopedias; instead it would’ve been mythically floating with other “phantom major leaguers,” a dubious list of players who reached the major leagues but never appeared in a game.

Yantz believed he would have played in more than one game in the big leagues had the Browns kept him in the fall of 1912. “The Browns could have used me,” he recalled in 1964. “The Cubs said I was too small and let me go.”23 None of the three Browns catchers who appeared in 40 or more games in 1913 batted higher than .208. Perhaps the last-place Browns would’ve been an ideal spot for an up-and-coming catcher like Yantz to get more major-league experience.

As it turned out, Yantz never got a second major-league game, but it wasn’t for lack of effort. He roamed through the minor leagues for four more seasons, beginning with the Southern Association’s New Orleans Pelicans in 1913.

Moving Yantz to The Big Easy wasn’t easy. The Cubs sold his contract to New Orleans in December 1912, but the National Association of Professional Baseball Clubs flagged the deal because Murphy forgot about a new rule requiring major-league players to pass through waivers before being sent to a minor-league club.24 The waiver wildness was sorted out and Yantz officially joined New Orleans in early March of 1913. While the incident didn’t spawn media mentions of an unofficial “George Yantz Rule,” the Cubs’ misstep was a reminder to other organizations that they had to follow the new waiver policy.

Yantz overcame his personal hesitation about joining the Pelicans; he was originally reluctant to go, claiming that every time he played in New Orleans for Birmingham he got “a touch of malaria.”25 (The New Orleans catching corps also included Louisville native Leo Angermeier, who played sandlot ball with Yantz as a kid.26)

Malaria didn’t end Yantz’s 1913 season, but a broken leg did. The injury happened in the second inning of a home game against Chattanooga on May 15 when Yantz stumbled while running to second base and broke a bone above his left ankle.27 This limited Yantz to just 44 games in 1913.

He regained his health and was ready to play again in 1914. New Orleans sold Yantz’s contract to the American Association’s Toledo Mud Hens in January.28 By May of 1914 he had been acquired by the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers, in a move that took extra time to execute because the Beavers thought Yantz might jump to the Federal League.29 Yantz kept his pledge to Portland and played in 65 games for the PCL champion Beavers.

On September 20, 1914, Yantz was behind the plate for a baseball rarity – a no-hitter loss. Portland lefty Johnny Lush threw nine hitless innings against the Venice Tigers, but the Beavers lost 1-0. The only run came in when a low pitch snuck past Yantz with a runner at third.30 It was the second time in PCL history that a pitcher had tossed a no-hitter but lost the game.31

Portland traded Yantz to Venice on October 27, 1914,32 but Yantz never played for the Tigers, who released him outright shortly before the 1915 season.33 It left Yantz looking for work until he signed with another group of Tigers, the Western League’s Lincoln Tigers, in May. Lincoln’s pitching staff included Bill Powell, the same pitcher Yantz caught in his only major-league game. Yantz played 90 games for Lincoln in his next to last season in professional baseball.

Yantz signed with the Central League’s Evansville Evas early in the 1916 season. Late in the year, he was popped in the head by an opponent’s knee and his doctor advised him not to play again that season.34 Yantz didn’t play in any future seasons either, retiring in 1917, ending a 10-year professional baseball career with one major-league stretch in 1912.35

After his professional playing career, Yantz worked full-time as a bricklayer, a job he held until his late 60s. He continued to play or manage amateur games in Indiana and Kentucky until his mid-50s, hanging up his catcher’s mitt for good at age 54 when he determined his eyesight was worsening.36 Yantz also stayed connected to baseball as a part-time scout; he is credited with discovering six-time major-league All-Star Paul Derringer when Derringer was a high-school pitcher in Springfield, Kentucky.37

Yantz’s wife, Eleanor, died in 1942 at age 53.38 They had one child, a daughter, Jacqueline, who occasionally performed with her accordion before Louisville minor-league games.39

Yantz’s record-tying big-league batting average had a legacy of its own in Louisville. In an 80th-birthday tribute in 1966, the Courier-Journal wrote that Yantz “is the only man in the all-time record books with a major-league batting average of 1.000.”40 That wasn’t true, and it still isn’t true, but the newspaper’s description illustrates the lore that Yantz’s hit carried in Louisville decades after it occurred.

Yantz rooted for Louisville’s minor-league clubs and watched major-league games on television in his later years.41 He was honored on the field between games of a Mets-Reds doubleheader on September 25, 1966, at Crosley Field’s Former Major Leaguers Day, recognizing anyone in the Cincinnati area who played at least one game in the majors.

It was likely the final time George Yantz stepped foot on a professional baseball field. He died at Louisville’s St. Joseph Infirmary on February 26, 1967, at age 80, leaving behind his second wife, Mabel, daughter Jacqueline, two grandchildren, and a perfect major-league batting average.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, FamilySearch.org, and the subject’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 “Falls to Death,” Kentucky Irish American, November 10, 1906.

2 “Medals for Best Players,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 17, 1907.

3 “Fetters Win Indoor Game,” Louisville Courier-Journal, March 7, 1908.

4 “League Gossip,” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 15, 1910.

5 “League Gossip.”

6 “Louisville Ballplayers Who Will Play in Professional Company Next Year,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 26, 1909.

7 “Molesworth Hits Again,” Birmingham News, June 14, 1911.

8 “Marathon Games,” baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Marathon_Games.

9 Johnny Carrico, “1.000 at Bat in Big Leagues,” Louisville Times, October 6, 1963.

10 “George Yantz, Baron Backstop, a Holdout,” Birmingham News, February 19, 1912.

11 “George Yantz Holds Out for More Money,” Montgomery Times, February 19, 1912.

12 “‘Hold-Out’ G. Yantz Reports to Moley,” Birmingham News, March 29, 1912.

13 “‘Hold-Out’ G. Yantz Reports to Moley.”

14 “Sport Conversation,” Birmingham News, September 18, 1912.

15 “Mayor Gives Up Keys of City,” Baltimore Sun, September 24, 1912.

16 “36 Candidates After Jobs on West Side Club,” Chicago Inter Ocean, December 22, 1912.

17 “36 Candidates.”

18 “Chicago Cubs Take Heckinger,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, September 23, 1912.

19 “Pittsburgh Again Outclasses Cubs,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, October 1, 1912.

20 Pittsburgh Again Outclasses Cubs.”

21 AccuWeather, email correspondence with senior meteorologist Tom Kines, December 31, 2019.

22 “George Yantz, Ex-Baseball Player, Dies.” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 27, 1967.

23 “1.000 at Bat in Big Leagues.”

24 “Cubs Recall George Yantz,” Chattanooga Times, January 22, 1913.

25 “Whole Team Must Have Had Malaria,” Birmingham News, February 26, 1913.

26 “Pel Catchers Are Old Pals,” Nashville Banner, January 14, 1913.

27 “Pels Blank Lookouts, Who Get But One Hit,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, May 16, 1913.

28 “Yantz Is Sold,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, January 28, 1914.

29 “May Come to Beavers and Then Again He May Not,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), May 7, 1914.

30 “Bricklayer and Ex-Ballplayer Gets 50-Year Union Card,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 4, 1956.

31 Pacific Coast League, 2019 PCL Sketch & Record Book (Round Rock, Texas: Pacific Coast League, 2019), 176.

32 “Coast League Cuts Salary Limit and 1 Umpire Is Ordered,” Oregon Daily Journal, October 28, 1914.

33 “Four Beavers Are Coming to Rest for Game,” Oregon Daily Journal, April 7, 1915.

34 “Sport Dope,” Evansville Press, September 2, 1916.

35 R.A. Cronin, “Byron Houck Seems to Have Arrived at End of Usefulness,” Oregon City (Oregon) Journal, May 15, 1917.

36 “1.000 at Bat in Big Leagues.”

37 Earl Ruby, “Ruby’s Report,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 24, 1966.

38 “Deaths and Funerals,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 20, 1942.

39 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Colonels Get 2 Hits, Lose 4th Place,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 15, 1939.

40 Ruby.

41 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Critics with Washboard See No Need to Rub It In,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 1, 1939.

Full Name

George Webb Yantz

Born

July 27, 1886 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

February 26, 1967 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.