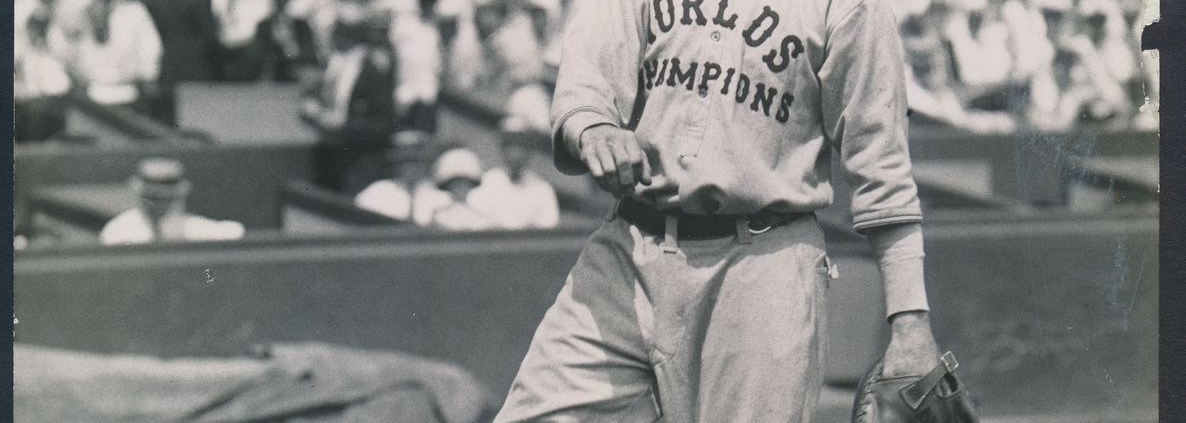

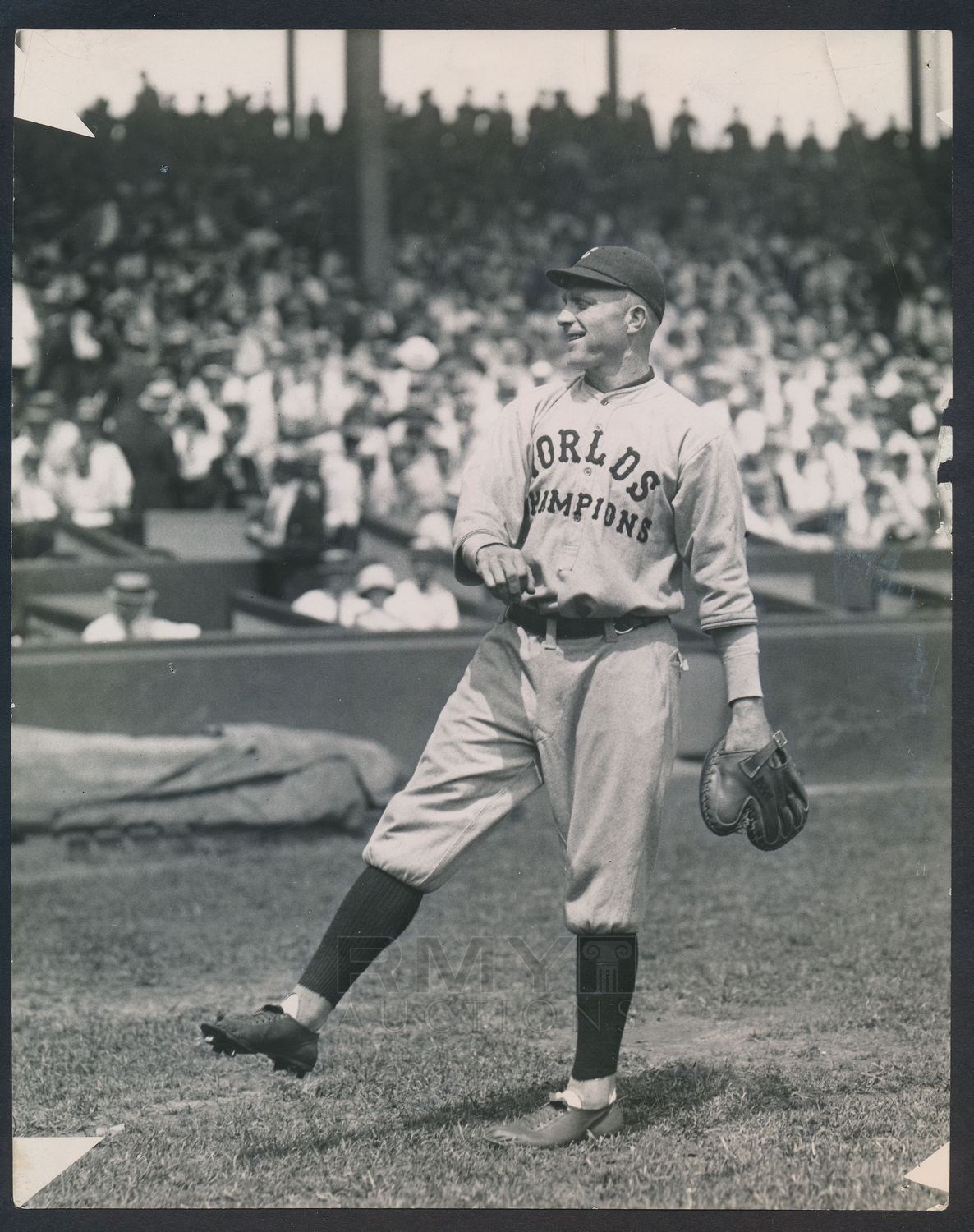

Ginger Shinault

A bit contributor behind the plate for the Cleveland Indians in the pennant chase of 1921, a perpetually upbeat and jovial teammate, and a tragic tuberculosis victim in his 30s — Ginger Shinault is a flamboyant figure from the Roaring Twenties.

A bit contributor behind the plate for the Cleveland Indians in the pennant chase of 1921, a perpetually upbeat and jovial teammate, and a tragic tuberculosis victim in his 30s — Ginger Shinault is a flamboyant figure from the Roaring Twenties.

Enoch Erskine Shinault (pronounced shi-NALT) was born on September 6, 1893, in Saline City, Arkansas. His parents were John R., who was a clerk at Baltimore Dairy Lunch, and Mary Elinor (Walker) Shinault. He had a sister, C.C., and two older brothers, Spain and Drew.

When Enoch was a lad, his father instructed him how to develop his speed, by capturing razorback “saws” (hogs) in the forest on their home farm. The boy also honed his throwing skills thanks to regularly tossing whole walnut shells.1 He also was known for endlessly playing the old sandlot game “one old cat.” Sad to relate, father John Shinault died soon after the turn of the century, so Enoch moved to live with his grandparents Napoleon and Yates Shinault in Byhalia, Mississippi, 30 miles from Memphis, Tennessee. By 1908, however, after grandfather Napoleon’s death, Enoch, Drew, and Spain lived in Memphis with their mother, who had remarried. The Shinault siblings were bequeathed a parcel of land by Napoleon, which court records show being sold at auction in Mississippi in early 1908.2

The next year shows the first documentation of Enoch playing amateur ball, a couple of hours west, around Little Rock, Arkansas, for the local Cubs congregation.3 As an 18-year-old, Enoch shared a residence with Drew, who was a clerk, then later a bookkeeper, at Memphis Gas and Electric. Enoch soon found work as a blacksmith at American Car and Foundry.

Eventually Enoch headed off to college. By 1914, he was playing outfield for the University of Arkansas, including a 25-game summer intrastate barnstorming tour against the Bedells semipro team.4 He also played for the Schaads in the Little Rock Inter-City League5 and for the local Fayetteville semipro team in the Commercial League.6

Shinault was invited to spring training by Memphis of the Southern Association in 1915.7 He was later farmed out to the Class C South Atlantic League, where he began his professional career as the Opening Day right fielder for Savannah.8 After just nine games, Shinault was demoted to Anniston of the Class D Georgia-Alabama League.9 He batted .171 there and was thus released after two weeks. He finished the summer playing for semipro teams in Ripley, Tennessee, and Forrest City, near Little Rock, with his “brilliant fielding” preserving a 3-0 shutout over Marianna.10

Still on option, Shinault again began 1916 in training camp with Memphis. It was there that he first donned the catching gear, on the suggestion of manager Dolly Stark. The experiment behind the plate did not go well, and Shinault was released. “Red” Shinault — this nickname was another nod both to hair color and persona — was angry, and later vowed to show Stark he could play the position.11 He received much-needed reps playing catcher for Monticello in the independent semipro Southeast Arkansas League, which included teams from Dermott, Warren, and Wilmar. His solo homer in the bottom of the 10th ended a scoreless tie, giving Monticello the victory over Wilmar.12

During this time, Enoch’s brother Spain also played some ball, also behind the plate, for the West Tennessee Normal School,13 then a semipro team in Coldwater, Mississippi.14

After playing the position for less than a year, Shinault opened 1917 as the starting catcher for Asheville of the North Carolina State League. He lost a week of playing time in April to a leg injury after being spiked in a game against Winston-Salem.15 On May 7 he was traded by the Tourists to the Columbia Comers of the Class C South Atlantic League for catcher Dick Manchester.16 The North Carolina State League disbanded at the end of May.

Shinault left the Comers and returned home to Memphis. Mickey Finn, the former Memphis skipper, recommended the idle Shinault to Jim Murray, manager of the Class D Western Association’s Oklahoma City Boosters, who were desperate for a catcher after a slew of injuries. Shinault immediately became the starting catcher. He hit two homers and two singles for the Boosters on June 14 against Denison,17 then a homer on July 4 against McAlester.18 He started at second base for much of the last two months of the season.

The Western Association did not commence operations in 1918. Shinault registered for the World War I draft and enlisted, but was never sent overseas, instead becoming a sergeant in an infantry regiment at Camp Pike in central Arkansas and a vital player on the regiment baseball team.19 The stocky catcher — all of 5-feet-10½ and 170 pounds — went 4-for-5 with two doubles as his Remount Station team defeated Fort Roots in July 1918.20 Later that summer, Shinault and Benn Karr led the 10th Training Battalion squad to a victory over the previously unbeaten Officers Training School team.21

With the end of the Great War, baseball was back in full swing, and Shinault signed with Rochester of the International League in February 1919.22 He hit only .227 in 41 games for the Hustlers, and was sent down to Waterbury of the Class A Eastern League in July. Shinault rebounded after joining the Brasscos, hitting .284 to finish out 1919, then .292 with 28 doubles and 15 stolen bases over a full season in 1920 for manager Jud Daley. During this time, in the offseason Shinault worked as a machine operator for the Illinois Central Railroad Company.

As a moniker, Red also represented Shinault’s intensity, as an Eastern League writer recalled:

“(Shinault) braced me near the clubhouse one day and berated me for something I had written about him the day before. ‘But I said you played even better than usual,’ I protested. ‘Damn it all,’ cried Ginger in his Dixie accent. ‘Ah always play better than usual!’”23

True to form, Shinault’s production caught the notice of multiple major-league teams. Even John McGraw’s Giants were said to be bidding for Waterbury’s Shinault by August.24 Yet as it developed, no major-league contract came to fruition in 1920. He worked during the offseason as a bolt header for American Car and Foundry back in Memphis, and spent many an afternoon with his favorite pastime: bird hunting.25

A 1921 preseason preview on the Eastern League said that Shinault, “behind the bat ought to be good for close to .300.”26 Before the season Waterbury traded Shinault to New Haven, the reigning league champion, for Red Torphy.27 Before Opening Day Shinault and New Haven squared off in a city championship with the collegiate Yale Elis.28 Shinault played well for Chief Bender’s New Haven bunch, hitting .309 with a slugging percentage of .526 for the local Indians. He was loaned to Rochester, one of his former teams, for four games in mid-June, before returning to New Haven. By now, Enoch had earned the nickname Ginger for his upbeat and peppery play.

On June 29 Shinault was sold by New Haven owner George Weiss to the Cleveland Indians for $10,000, a record sum for an Eastern League player.29 The Sporting News wrote that “he comes highly recommended as the best backstop seen in the Eastern League in several seasons.”30 Five days later, Shinault made his major-league debut for the first-place Indians, who were the defending league champions, in the second game of a July 4 doubleheader against the White Sox. Even in his first game, Ginger, who drove in two runs, was given credit for the in-game comeback of the Indians, who roared back from a 10-1 deficit to defeat Chicago 11-10, with a strong effort in long relief by Guy Morton.31 The Cleveland Plain Dealer commented that Shinault “caught Guy Morton as though he had been catching big league hurlers all his life.”32

Shinault’s fielding, however, was soon exposed at the major-league level. A couple of weeks after his debut, the Plain Dealer reported that Shinault “tried out his throwing arm by hurling Miller’s bunt to the right field wall, thus breaking the American League’s throwing record for catchers.”33

Shinault’s playing time behind the plate was slated to ratchet up after starter Steve O’Neill’s knee injury, followed by backup Les Nunamaker’s broken leg suffered on August 13.34 Ginger even earned the affection of player-manager Tris Speaker, who liked him because “he is a talker and keeps the whole team up and doing.”35 Nonetheless, the Indians also recalled rookie catcher Luke Sewell from Indianapolis. In a start on September 2, Shinault went 3-for-4, with his only extra-base hit of the season, a double off Bert Cole, in the Indians’ 12-1 blowout over Detroit.

As of September 16, with a robust .436 (10-for-23) mark, Shinault was leading the American League in average, though obviously he was well short of qualifying for a batting crown.36 But he went 0-for-4 over the final two days of the season, dropping him from a high point of .440 down to .378 (11-for-29) for the second-place Indians, who had stumbled down the stretch against the Yankees. Still, that average placed Shinault on the final league batting list for 1921 (disregarding sample size), just above George Sisler and one notch below two guys named Cobb and Ruth.37 The then-accepted threshold for winning a batting title was appearing in 100 games.

Unfortunately for Shinault, he finished next-to-last in AL fielding for catchers (here too, the lists published by newspapers were not filtered with any cutoff point).38 He committed four errors and surrendered nine stolen bases during his short time behind the plate. Still, Shinault was voted a half-share, or roughly $500, for the Indians second-place finish.39

Heading into the Indians’ spring training of 1922 held in Dallas, there were whispers of Shinault possibly relieving incumbent O’Neill of much of the catching responsibility.40 Ultimately, O’Neill returned healthy and productive. When Ginger did play in 1922, he was erratic. In one May game, the Plain Dealer wrote, “Shinault brought in another with a throw that hit Umpire (George) Hildebrand instead of (third baseman) Larry Gardner’s glove.”41 In one of his last games for Cleveland, he neglected to tag a runner at home, thinking it was a force play.42 Shinault barely played, starting only twice, hit .125 (2-for-16) in spot duty, and finally was optioned to Kansas City of the American Association in August.43

After the 1922 season, Cleveland sent Shinault, still on option, along with four other players and $75,000 to Milwaukee for catcher Glenn Myatt.44 Ginger hit .297 as the starting catcher for the Brewers in 1923, playing alongside young outfielder Al Simmons. At the end of the season, Shinault was loaned by Milwaukee back to Kansas City for the Blues’ Little World Series matchup against Baltimore of the International League.

Injuries limited Shinault to 84 games for Milwaukee in 1924, but he still hit .285. In June, in nearby Chicago, Shinault wed Jean Roberts, whom he had met in Palmetto, Florida, during Milwaukee’s spring training. The day of their initial encounter was the same day in which Shinault homered against Brooklyn in an exhibition game.45 At the end of the 1924 regular season, Shinault and many of the Brewers went barnstorming through Wisconsin and neighboring states, borrowing Rube Walberg from the Philadelphia Athletics among others for the tour.46

In February 1925 Shinault was traded by the Brewers, along with Beauty McGowan and two others, to the Association’s Kansas City team for Bunny Brief, Bill Skiff, and George Armstrong. Ginger was said to be “pleased with the exchange.”47 He hit .293 with 27 doubles in 113 games for the Blues. On August 4 in Kansas City, the Shinaults welcomed a daughter, Zoe, into the world.

Shinault returned to Kansas City for the 1926 season. That September he reached base an incredible 17 times in a row in a series against his former team Milwaukee.48 Shinault’s second tenure with the Blues lasted through the 1927 season. In Kansas City Ginger was “loved by the players because of his gentleness, and yet had a remarkable faculty for being able to entertain.”49

Before the 1928 season, first baseman Dudley Branom (purchased for a Double-A record $12,500) and Shinault were sent to the American Association’s Louisville team by Kansas City.50 Shinault was genuinely sad leaving, after three years in the community, stating: “I’m crazy about Kansas City and next winter I’ll be back here to live.”51 Regarding the trade, even manager Dutch Zwilling “first debated a long time with himself before he could muster up enough courage” to inform the popular Shinault. Louisville soon traded Ginger, in May, again within the American Association, to Columbus.

During the offseason before the 1929 campaign, Shinault worked locally in Columbus as a salesman at the local Goldman Jewelry Company. He re-signed with Columbus and reported to Lakeland, Florida, in March for spring training.52 Later that month, Shinault represented the Senators at the memorial in Orlando for Roy Meeker, who had collapsed and died before a Senators exhibition game.53 Shinault hit .291 in 117 games for Columbus in 1929.

Columbus traded Shinault back to Milwaukee in early April 1930, but he quickly became expendable to the Brewers after they purchased the contract of catcher Merv Shea from the Detroit Tigers. Milwaukee traded Shinault to Little Rock of the Class A Southern Association by the end of the month.54 At the end of May, Shinault faced Whitey Glazner, his Anniston batterymate from 15 years prior.55

As the Travelers’ starting receiver, Shinault hit .306, his highest batting average ever for a season. By July, however, fatigue started taking its toll on the catcher as he worked in games for Little Rock.56 The Travelers were forced to finally sign veteran receiver Bill Smith to replace Shinault on the roster.

Shinault soon suffered a severe hemorrhage on July 22. Tests revealed that he had contracted tuberculosis, as well as acute lung damage.57 He was forced to quit the game, also adhering to doctors’ suggestions that he move to Colorado, which was a popular destination for people with TB because of its higher altitude and dry climate. On August 19 the Travelers hosted a “Shinault Night,” raising money for the ill ballplayer out West.58 His old employer in Kansas City, the Goldman Jewelry Company, sent Shinault a Bulova watch, while imploring him to get “hale and hearty soon.”59

Shinault showed some signs of recovery while in Colorado in the early fall. But he lapsed into unconsciousness for three days in late December. With wife Jean at his side, he died at Fitzsimons General Hospital in Denver — known as a tuberculosis treatment center — on December 29, 1930. By coincidence, Shinault was not the only former Little Rock player and big leaguer to pass away on this day. George Stutz also died unexpectedly in his Philadelphia home.60

A Kansas City paper wrote, “[O]ne of the most willing players ever to wear a Blue uniform, ‘Ginger’ always was a great favorite here.”61 As another paper put it, “Shinault joined the Travelers after the season began … and immediately became a big asset to the club, as well as popular with the fans.”62 Shinault was buried at Forest Hill Cemetery Midtown in Memphis.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and MyHeritage.com Birth, Marriage, and Death Records.

Notes

1 “The Pepper Pot of the Booster Baseball Club” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), July 8, 1917: 13.

2 “Non-Resident Notice: Roper vs. Spain Shinault, et al,” DeSoto Times (Hernando, Mississippi), February 28, 1908: 4.

3 “Cubs 7, Zu Zu’s 2,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), April 26, 1909: 8.

4 “Bedells Again Defeat U. of A.,” Pine Bluff (Arkansas) Daily Graphic, July 2, 1914: 5.

5 “Schaads and Tuchs Take the Openers of Inter-City League,” Arkansas Democrat, April 13, 1914: 8.

6 “Fayetteville Is Again Defeated,” Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), July 4, 1914: 8.

7 “Three Chicks Released; Lord Retains Options in Trio of Promising Recruits,” Chattanooga Daily Times, April 30, 1915: 11.

8 “South Atlantic: Babies 6, Indians 1” Atlanta Constitution, May 9, 1915: 3.

9 “G.A. League News and Views,” Anniston (Alabama) Star, May 16, 1915: 8.

10 “Pat Folbre Wins Again,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, July 10, 1915: 9.

11 “Shinault Driven into Majors,” Sacramento Bee, November 21, 1921: 6.

12 “Homer in Tenth Scores Only Run,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, September 6, 1916: 7.

13 “A Runaway Result,” Jackson (Mississippi) Daily News, March 28, 1916: 5.

14 Senatobia (Mississippi) Democrat, March 23, 1916: 8.

15 “Baseball Notes,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, April 27, 1917: 8.

16 “Dick Manchester Is Now a Real Tourist,” Asheville Citizen-Times, May 8, 1917: 8.

17 “Homers Win for Boosters,” Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, Oklahoma), June 15, 1917: 8.

18 “Boosters and Miners Divide Double Bill,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), July 5, 1917: 10.

19 “Ginger Shinault,” Denver Post, December 30, 1930: 6.

20 “Remount Station Wins,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, July 28, 1918: 3.

21 “Student Officers Lose First Game,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, August 19, 1918: 3.

22 “Rochester’s Men Train with N.Y.,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, February 27, 1919: 11.

23 Dan Parker, “Broadway Bugle” Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey), May 15, 1956: 21.

24 “Eastern League Players in Great Demand Now,” Washington Times, August 6, 1920: 14.

25 Baseball Hall of Fame Records: Enoch Shinault.

26 “Many Pennants Won in Eastern in January,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1921.

27 “‘Red’ Torphy Popular with Waterbury Fans,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Evening News, July 2, 1921: 9.

28 “Bender’s Players Defeat Yale, 8 to 4,” Boston Globe, April 21, 1921: 9.

29 “Cleveland Indians Pay $10,000 for Kid Catcher,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1921: 15.

30 “Indians Not Uneasy as Yanks Threaten,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1921: 1.

31 “Ginger Makes Good Start,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 5, 1921: 17.

32 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 5, 1921: 17.

33 “Pick on Caldwell and Morton, but Dunn’s Real Jinx While Tribe’s Boss Houses Thirteen Persons,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 18, 1921: 13.

34 “Tribe Takes Another Game from White Sox” Canton (Ohio) Repository, August 14, 1921: 33.

35 “Ginger Shinault Getting Along Fine,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, September 10, 1921: 5.

36 “Individual Batting,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, September 17, 1921: 11.

37 1921 American League Batting Leaders.

38 “American League Fielding Averages,” Washington Evening Star, December 22, 1921: 31.

39 “Speaker Refuses to Say,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 5, 1921: 17

40 “Waiting for the Call to the Big Time,” South Bend Tribune, February 25, 1923: 14.

41 “Indians Lose 11-9 Game at St. Louis/Fall Before Browns for Third Time in Row,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 1, 1922: 18.

42 “Crowd Begs Ken Williams to Plank His 20th Homer,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 1, 1922: 14.

43 “Night News Summary,” Chillicothe (Ohio) Gazette, August 2, 1922: 7.

44 “Cleveland Gets Myatt,” Kansas City (Missouri) Star, December 31, 1922: 6.

45 “Milwaukee Catcher Weds,” Miami Herald, June 5, 1924: 12.

46 “Brewers Bring Star Hurler to Pitch Saturday,” Marshfield (Wisconsin) News-Herald, October 9, 1924: 3.

47 “The Blues Hanford Bound,” Kansas City Times, February 24, 1925: 12.

48 “It Took Milwaukee a Long Time to Stop Him,” Kansas City Times, September 7, 1926: 8.

49 “The End to Shinault,” Kansas City Star, December 30, 1930: 10.

50 “Branom and Shinault Purchased by Colonels,” Courier-Journal (Louisville) April 4, 1928: 15.

51 “A Good Day for Blues,” Kansas City Times, April 4, 1928: 8.

52 “Shinault to Sign Columbus Contract,” Kansas City Times, January 26, 1929: 14.

53 Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune, March 27, 1929: 6.

54 “Travelers Buy Ginger Shinault, Brewer Catcher,” (Nashville) Tennessean, April 30, 1930: 12.

55 “Pelican Homers Rain; Pebbles Crushed, 12-3,” Chattanooga Daily News, May 30, 1930: 11.

56 “Death Calls Last Strike on Enoch Shinault,” Denver Post, December 30, 1930: 4.

57 “Shinault, Ill, Quits Game,” Kansas City Times, July 28, 1930: 12.

58 “Barons Subdue Chicks; Birds Beat Lookouts,” Courier News (Blytheville, Arkansas), August 20, 1930: 6.

59 Baseball Hall of Fame Records: Enoch Shinault.

60 “Former Little Rock Ball Players Dead,” Chattanooga News, December 30, 1930: 8.

61 “The End to Shinault,” Kansas City Star, December 30, 1930: 10.

62 “Peb Catcher Dies,” Chattanooga Daily Times, December 30, 1930: 9.

Full Name

Enoch Erskine Shinault

Born

September 7, 1892 at Benton, AR (USA)

Died

December 29, 1930 at Denver, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.