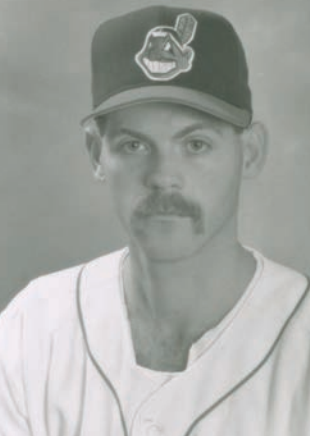

Gregg Olson

Gregg Olson, the only son of a highly successful high-school baseball coach, distinguished himself on the diamond at Omaha’s Northwest High School and went on to “pioneer the position of late inning college closer at a time when no one put their most talented pitcher in the bullpen.”1 That talent made him a first-round draft pick and an almost immediate major-league star. His mound dominance lasted for five years until he was sidelined by a serious arm injury. After trying for four frustrating years to recover his mastery, he finally found new life with an expansion team and added four years to his résumé.

Gregg Olson, the only son of a highly successful high-school baseball coach, distinguished himself on the diamond at Omaha’s Northwest High School and went on to “pioneer the position of late inning college closer at a time when no one put their most talented pitcher in the bullpen.”1 That talent made him a first-round draft pick and an almost immediate major-league star. His mound dominance lasted for five years until he was sidelined by a serious arm injury. After trying for four frustrating years to recover his mastery, he finally found new life with an expansion team and added four years to his résumé.

Greggory William Olson was born on October 11, 1966, in Scribner, Nebraska. His parents were Bill and Sandra “Sandy” (née Cassell) Olson. In 1971 the family, which by then included younger sister Tammi, moved to Omaha when Gregg’s father became the first baseball coach at Northwest High. Gregg grew up there, playing youth football, basketball, and baseball throughout his childhood.2

Olson credited his father with shaping him “into a major leaguer.”3 A significant component of that process was teaching the youngster at age 13 to throw the curveball that would become his trademark “Uncle Charlie,” but for a year limiting him to one per game.4

In 1982 Gregg joined his father’s baseball squad at Northwest High, and over the next four years, the Huskies won four Class-A state championships as Gregg compiled a 27-0 record and a microscopic 0.76 ERA while fanning 276 opposing batters.5 After the third of those championships, the father and son were featured in Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd,” which noted Gregg’s performance in the championship game when he “struck out 10, hit two homers, and drove in all four Husky runs.”6

That article also cited Northwest’s 40-game winning streak, which had begun in 1983. The streak ended at 53 games in 1985, Gregg’s senior year, but the Huskies won their fourth consecutive title, and Gregg capped his high-school career by hitting .857 (18-for-21) in the state tournament and throwing a no-hitter (the fourth of his career) in the championship game.7

Gregg’s high-school teams were ranked among the top three nationally by Collegiate Baseball magazine for three consecutive years (1983-85).8 In 1984 he was a member of the USA Junior Olympic Team that won a Silver Medal,9 and he was named a High School All-American in 1985.10 With that track record, college baseball was the logical next step, so Gregg passed up a football scholarship from the University of Nebraska.11 From some 30 Division I baseball offers, he chose a “full ride” from Auburn University because he would be able to “play right away” for Hal Baird, whom he considered “an exceptional pitching coach.”12

In his first collegiate year, Gregg made 14 starts, completing one, and relieved in five other games. He compiled a 7-3 record with a 5.72 ERA and 62 strikeouts (0.79 per inning).13 The next year, Coach Baird “changed the college game forever”14 by giving the big (6-foot-4, 210-pound) right-hander what was at the time a new role. He became the Tigers’ closer, appearing in 78 games over the next two years, compiling an 18-4 record with 20 saves and fanning 209 batters (1.4 per inning).

After leading the NCAA with a 1.26 ERA in 1987, Olson was named an All-American by Baseball America. He then played on the USA National Team that handed Cuba two home losses in July. That team went 8-0 in the Pan American Games in Indianapolis before losing the championship game to those same Cubans. Olson was a vital part of Team USA’s success, appearing in 21 of its 56 games, amassing a 3.53 ERA, and leading the team with 69 strikeouts.15

In 1988 Olson’s 2.00 ERA led the Southeastern Conference, and he became Auburn’s first two-time baseball All-American.16 Following that successful junior year, the Baltimore Orioles made him the fourth overall pick in the 1988 amateur draft – the highest pick ever for a college relief pitcher17 — and offered him a contract that stipulated that he would be in the majors by September 1.18 He had also been selected to play for Team USA in the 1988 Olympics, but contracted mononucleosis and was unable “to finish the Olympic experience.”19

On June 28, 1988, Olson signed with the Orioles for a reported bonus of $200,00020 and was assigned to Hagerstown in the Class-A Carolina League to begin his professional career. After closing eight games and earning one win and four saves for the Suns, Olson was promoted to Double-A Charlotte. He pitched in only eight games there before he and teammate Curt Schilling were summoned to join the Orioles in Seattle.21 During that brief stint in Charlotte, Olson acquired the nickname (“Otter”) that Schilling brought to the majors with them and that followed Olson throughout his career.22

Olson made his major-league debut in Seattle on September 2, 1988, entering the game in the bottom of the eighth inning with nobody out and a runner on first and the O’s trailing, 3-1. He fanned Steve Balboni on a called third strike. The next hitter singled but was out at second trying for a double. After issuing a walk, Olson retired the side with another strikeout. In the ninth, after the Orioles scored three times, Tom Niedenfuer held the Mariners scoreless, and Olson had his first major-league victory. He pitched 10 more innings that year and was charged with one loss and no saves.

Olson staked his claim to the Baltimore closer’s job early in 1989. He earned his first save on April 15 in Boston in his fifth appearance. He followed that performance with two middle-relief stints and a three-inning closing effort against the Twins that earned him a win. On April 26 Olson earned what he later called “my first real save”23 when he entered a game in Oakland in the bottom of the eighth with the Orioles leading 2-1. After retiring the side in order, he returned in the ninth and struck out Dave Parker, Dave Henderson, and Mark McGwire to preserve the win. It was the second save of his career, and he was now the Orioles’ closer. He converted his first 15 save opportunities, went through a brief slump in July, and finished the season with 27 saves in 33 opportunities.

Late in the season, manager Frank Robinson said of Olson, “I don’t know where we’d be without him” but added, “He always makes it interesting.”24 It seems that 1-2-3 innings were not Olson’s usual approach. One Baltimore sportswriter described his season this way: “Close game. He pitches into trouble. He pitches out of trouble. Orioles win.”25 Unfortunately for the Orioles, he didn’t always pitch out of trouble. In his last appearance of the season, he had a rare blown save when his wild pitch allowed the Toronto Blue Jays to tie and eventually win a game that gave them a two-game lead over the Orioles with only two games left to play. Another loss the following day ended the Orioles’ hopes of a pennant.

It had, however, been a turnaround year for the Orioles – climbing from the AL East cellar in 1988 to a second-place finish. Olson’s role in that transformation was rewarded when he was named AL Rookie of the Year, the first relief pitcher to be so honored. On December 16, 1989, he made the year even more memorable by marrying Jill Johnson, whom he had met on a blind date during his junior year at Auburn.26

Olson followed his outstanding rookie season with another stellar year, being named to his only All-Star team by Oakland Athletics manager Tony La Russa and finishing the season with 37 saves, his career high and an Orioles’ record until it was eclipsed in 1997 by Randy Myers’ 45 saves. That was the first of three consecutive 30-plus-save seasons during which Olson became (at age 25) the youngest player at the time to record 100 saves. Perhaps the most unusual and historic of those saves occurred at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum on July 13, 1991. Olson came into the game to start the bottom of the ninth inning with the Orioles leading the Athletics, 2-0. He was the O’s fourth pitcher of the game, after Bob Milacki (6 innings pitched), Mike Flanagan (1 IP), and Mark Williamson (1 IP), and he was trying to preserve their combined no-hitter. He needed only 12 pitches to do just that, getting Dave Henderson to ground out and fanning Jose Canseco and Harold Baines.

When the 1993 season started, Olson had established himself as one of the premier closers in the league, and he was headed for yet another 30-plus saves until disaster struck on July 31. He entered a game in the ninth inning to protect a 4-0 lead over the Red Sox (a non-save situation). He did his job, striking out the side. He later called that game’s final strike, which fanned Mo Vaughan, his “best curveball EVER,”27 but it also was his worst curveball ever because it resulted in a torn ligament. That injury did not receive immediate attention as he pitched in four games over the next eight days. He earned saves in the first three of these appearances to bring his season total to 29 and lowered his ERA to a career-best 1.60, but on August 8 he allowed an inherited Cleveland runner to score a tying ninth-inning run. The Orioles eventually won that game in extra innings, but Olson’s career in Baltimore was over. He faced (and walked) only one more batter that season (on September 22).

In August, the orthopedic surgeon Frank Jobe had recommended Tommy John surgery to repair the damaged elbow, but Olson wanted to avoid the knife.28 He talked with Nolan Ryan, who had rehabbed through a similar injury, and decided to try Ryan’s approach. In January 1994, Dr. James Andrews found that the ligament had fully healed although such tears rarely mend on their own. But Olson had not paid enough attention to his mechanics,29 and he was no longer the pitcher he had been.

In his five full seasons with the Orioles. Olson had become a fan favorite, relying on his knee-buckling curveball and a “90-plus-mph fastball”30 to earn 160 saves, a team record that has stood for more than years. He also set the franchise record of 41 consecutive scoreless innings (in 29 appearances between August 4, 1989, and May 4, 1990). When asked about that streak, Olson said, “I don’t think of it as a streak. Cal Ripken has the Streak. This was just a little run.”31

Considering what he accomplished in Baltimore, it is not surprising that Olson was hurt when, in his words, “Baltimore ditched”32 him after the 1993 season, opting not to risk arbitration with an injured pitcher. The Orioles tried unsuccessfully to develop a mutually acceptable “incentive-laden”33 contract, and so many other teams showed interest that during January 1994 every issue of The Sporting News included articles related to some aspect of the “Olson Derby.”34

Although it didn’t take him long to find a new team, Olson was about to begin what he later called “a run of total, frustrating hell.”35 Despite the disappointments and frequent uniform changes, he never considered quitting. He no longer felt “invincible,” but he got close enough often enough to being what he had been36 that he was sure there was light at the end of the tunnel. Eventually, he was correct, but the tunnel was longer and bumpier than he expected.

Olson signed in February 1994 with Atlanta. His one-year contract was for less than he had made in Baltimore, but included a potential bonus if he was healthy enough to pitch in 60 games.37 In one of life’s (or at least baseball’s) little ironies, pitcher Greggory William (Gregg) Olson signed with the Braves just two months after Atlanta released catcher Gregory William (Greg) Olson. The two “namesakes” had met only once – in 1990 when they were on opposing sides in the All-Star Game, staying in the same Chicago hotel, and dealing often with the confusion of receiving each other’s phone calls, messages, and laundry.38

Olson’s Atlanta bonus money was in doubt from the outset; he went on the disabled list during spring training, rehabbed in Richmond, and then struggled through the season, appearing in only 16 games and compiling a record of 0-2 with a single save and a 9.20 ERA. The Braves released him at the end of the season, and Olson spent the next three years (1995-97) trying to resurrect his career.

That quest took him to seven major-league teams and three minor-league affiliates. His journey began when he signed with Cleveland after being released by the Braves. He also considered returning to Baltimore, but decided that Cleveland’s need for a relief pitcher was greater.39 He started the 1995 season with Triple-A Buffalo and then joined the Indians, where he compiled an ERA of 13.50 in three games. In mid-July, his wife was at home expecting their first child, and the Indians were scheduled for a 10-day road trip after the All-Star break. The team denied Gregg’s request to be released but allowed him to miss the road trip so he could be at home for the birth.40 Shortly afterward, Kansas City purchased his contract. His numbers with the Royals were much more respectable – three saves, a 3-3 record, and a 3.26 ERA in 20 appearances, but in November he again became a free agent when Kansas City’s best offer for the next year was a minor-league contract.41

The Olson merry-go-round moved even faster in 1996; he became the property of four major-league teams, but played for only two. The St. Louis Cardinals signed him in January, but released him after he was injured during spring training.42 The Cards having traded for Dennis Eckersley shortly after acquiring Olson probably made him more expendable.43 Cincinnati signed Olson immediately; assigned him to Triple-A Indianapolis, where he earned four saves in seven appearances; and traded him to Detroit in late April for infielder Yuri Sanchez, who would spend 14 years in the minors without ever making it to “The Show.”

Olson appeared in 43 games (43 innings) for the Tigers, earning eight saves and compiling a 3-0 record and a 5.02 ERA, before being traded in late August to Houston, where he appeared in nine games and earned another win. When the Astros released Olson in October, he was once again a free agent, but while with Detroit he had added a pitch to his repertoire that he later credited with helping him in his comeback efforts. Olson said that Tigers pitching coach Jon Matlack taught him to throw a changeup, giving him “a pitch nobody expected.”44

Olson’s road back had a few more stops. He signed with Minnesota in December 1996, and opened the 1997 season with the Twins. In 11 games, his ERA was an astronomical 18.36, and he was released in the middle of May. The Royals signed him again a week later and returned him to his hometown Omaha Royals, where for the first time in years he was used as a starter as well as reliever. He pitched in nine games, starting five and closing two others, compiling a 3-1 record and a 3.31 ERA, and was promoted to Kansas City in July. In 34 games (41⅔ IP), mostly as a middle reliever, his ERA (3.02) was the lowest since his final year in Baltimore, perhaps because his strikeout-to-walk ratio (1.65) was also his best since that same year. Olson later credited Royals coach Bruce Kison with helping him regain his earlier form. He said, “With the Royals I started feeling like my old self. It began coming naturally again.”45 Even so, he was released in October.

In the spring of 1998, Olson appeared in the training camp of the brand-new Arizona Diamondbacks, one of the National League’s two expansion teams. He made the team and was expected to be the setup man with Felix Rodriguez as the closer.46 That was his role on April 20, when he entered a duel of the expansion teams at Bank One Ballpark in Phoenix with Arizona leading Miami 7-4. The Diamondbacks continued to add runs, and Olson stayed in the game for 2⅔ innings. As a result, he found himself in an unfamiliar spot – the batter’s box. He had batted twice before in the majors – once in Baltimore, once in Atlanta – and had struck out both times. He batted twice in this game, striking out again in his first appearance. In his second at-bat, he smashed a two-run homer off right-hander Oscar Henriquez. He would walk in his only other major-league plate appearance, so upon retirement he became the 12th member of an elite club47 — players whose only major-league hit was a home run.

In May, with Rodriguez’ ERA hovering around 7.00, about twice as high as Olson’s, their roles were reversed. On May 1, Gregg closed his first game as a Diamondback, pitching the last two innings of a loss to the Expos. Three days later, he pitched the 10th and 11th innings against the Mets and earned his first win. After two more middle-relief appearances, Olson garnered his first save on May 14 with a perfect ninth inning against the Brewers to preserve a 4-1 victory. At that time, the Diamondbacks owned an 8-31 (.205) record. From that point forward, with Olson closing another 46 games, earning 29 more saves, and lowering his ERA from 4.08 to 3.01, Arizona’s record was 57-66 (.463).

Among those 29 saves was perhaps the oddest of Olson’s career. On May 28 he entered a game in the bottom of the eighth with Arizona clinging to a 7-5 lead over San Francisco. The Giants had already scored twice in the inning and had a runner on first with two outs and Barry Bonds at the plate. Gregg walked Bonds and then threw a wild pitch that put the tying runs in scoring position. He issued another walk to load the bases before fanning Rey Sanchez to end the inning. The Diamondbacks scored once in the ninth to gain a three-run cushion, and Olson stayed in the game. After fanning the leadoff batter, he issued two more walks, a double, a run-scoring groundout, and yet another walk, bringing Bonds back to the plate with the bases loaded and Arizona’s lead reduced to two runs. Following manager Buck Showalter’s orders, Olson intentionally walked Bonds to force in another run. That rare48 strategy “worked,” but it took a while. Brent Mayne fouled off five full-count pitches before drilling a line drive that the right fielder lost in the lights before making a “dramatic, game-ending catch.”49 Arizona prevailed, 8-7, and Olson earned a save while giving up two runs on one hit and six walks (only one of which was intentional). He had thrown 56 pitches to record four outs.

At the end of the season, another Greg (Padres’ outfielder Greg Vaughn) was named NL Comeback Player of the Year by The Sporting News and by the Players Choice Awards program. Vaughn had an All-Star season (.272/50 home runs/119 RBIs), which was vastly better than his previous year (.216/18 homers/57 RBIs), but did his bouncing back from one bad year outweigh what Olson accomplished for the Diamondbacks after four years as a baseball vagabond? Perhaps the voters found it easier to recognize a rapid rebound from a single bad season than to recall how good Olson had been five years earlier and how long and often discouraging his comeback road had been. Olson’s performance did receive some recognition; Arizona’s baseball writers named him the Diamondbacks’ Most Valuable Pitcher.50

In 1999, for the first time in five years, Olson did not have to look for a new ballclub; Arizona was happy to have him back. Even with a 30 percent raise (to $850,000), he was a bargain. His numbers declined a bit as he returned to a set-up role after blowing several saves early in the season51 and spending time on the disabled list because of back spasms,52 but he appeared in 61 games, earning 14 saves to go with a 9-4 record (his career high in wins) and a 3.71 ERA. When the Diamondbacks won the NL West, Olson got his only (and very limited) postseason experience, facing two batters in two games, and being charged with the game-tying run (unearned) in the deciding game of the Division Series won by the Mets.

After that season, Olson again tested the free-agent market. Now, however, he had two successful seasons on which to base negotiations, and he landed a guaranteed two-year $3 million contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers. However, he went on the disabled list early (on April 11) – with a strained right forearm. He then tore a tendon in the same arm while on the mound in a rehab assignment in Class-A San Bernardino.53 He appeared in only 13 games (17⅔ IP) in 2000, acquiring one loss and no saves. The following year, his performance deteriorated even further. On June 22, 2001, he entered a game in the top of the ninth with one out and two runners aboard. The visiting Padres had already scored twice to take a 6-4 lead. Olson gave up a walk, a sacrifice fly, and a hit. When he finally retired the side, both inherited runners had scored, he had been charged with a run, and the Padres had a 9-4 lead.

That was Gregg Olson’s last game in the major leagues. After 28 games, he had an 8.03 ERA, a record of 0-1, and no saves. In his last four games, he had been charged with 10 runs (all earned) in 3⅓ innings (a 27.00 ERA) – an inauspicious end to an amazing comeback. Olson himself said that “it wasn’t a total surprise”54 when the Dodgers announced his release.

Olson, his wife, Jill, and their four children (Brett, Brooke, Ashley, and Ryan) remained in Newport Beach, California, where they had moved in 2000. Brett, a right-handed hitter and pitcher55 like his father, joined the Auburn baseball team as an infielder in 2015. Gregg served for four years as an advance scout for the San Diego Padres and became part-owner and president of Toolshed Sports International, a manufacturer of high-performance athletic undergear.

Olson was inducted into the Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame (along with his father) in 1999. That same year, Sports Illustrated named him one of Nebraska’s “Fifty Greatest Sports Figures of the Century.”56 In 2001, his plaque was placed on “Tiger Trail” in downtown Auburn, Alabama, which honors former Auburn University athletes. In 2008 he was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame, and two years later, he was one of the first four players (along with Frank Thomas, Bo Jackson, and Tim Hudson) to be enshrined on the Wall of Fame at Plainsman Park, Auburn’s baseball stadium.

In 2013 Olson became associated with yet another honor when he agreed that his name could be attached to a new annual award that would recognize college baseball’s “Breakout Player of the Year.” This award, sponsored by Toolshed Sports International, recognizes a player who receives no preseason All-American mention but “elevates his game to an elite level”57 during the season. The winner of the inaugural 2013 Gregg Olson Award was Ball State pitcher Scott Baker.

Olson also co-edited and contributed several stories to We Got to Play Baseball: 60 Stories from Men Who Played the Game. In his “Dedication” to that volume, he wrote: “Baseball is a great life, but not an easy one.” His own career certainly supports that belief.

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Books

Olson, Gregg, and Ocean Palmer, ed. We Got to Play Baseball: 60 Stories from Men Who Played the Game (Houston: Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Company, 2012).

Newspapers

Baltimore Sun.

Los Angeles Times.

Sports Illustrated.

The Sporting News.

Washington Post.

Online Resources

Auburn Tigers Baseball (auburntigers.com).

Baseball Almanac (baseball-almanac.com).

Baseball Cube (thebaseballcube.com).

Baseball Library (baseballlibrary.com).

Baseball-Reference.com (baseball-reference.com).

City of Auburn, Alabama (auburnalabama.org).

Gregg Olson Award (olsonaward.com).

MLBlogsNetwork (mlb.com).

Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame Foundation (nebhalloffame.org).

Retrosheet (retrosheet.org).

SB Nation: The Good Phite (thegoodphite.com).

The Sports Illustrated Vault (si.com/VAULT).

Personal Correspondence

For six weeks, starting in mid-December 2014, the author and Gregg Olson exchanged voicemails. Between January 9 and 11, Olson reviewed a first draft of the biography and provided feedback and answers to questions raised by the author. In a January 26, 2015, telephone discussion, after reading a revised draft, Olson answered additional questions, discussed his career, and approved the biography.

The author is also indebted to Richard French, his former neighbor in Atlanta and Gregg Olson’s college roommate, for making the introduction that facilitated this effort.

Notes

1 Hal Baird, head baseball coach at Auburn University (1985-2000), quoted on olsonaward.com.

2 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

3 Gregg Olson, “Introduction” to We Got to Play Baseball (Houston: Strategic Book Publishing, 2012), xii.

4 Jonathan Hacohen, “Gregg Olson Interview: Talking Ball with One of the Greatest Closers in MLB History,” MLBreports.com, April 6, 2012.

6 Sports Illustrated, July 16, 1984.

8 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

9 Gregg Olson, “Jim Abbott: Troublemaker in Cuba,” We Got to Play Baseball (Houston: Strategic Book Publishing, 2012), 26.

11 Ibid.

12 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

13 The Baseball Cube (thebaseballcube.com).

15 Ibid.

18 Hacohen.

19 Gregg Olson, “Jim Abbott: Troublemaker in Cuba,” We Got to Play Baseball (Houston: Strategic Book Publishing, 2012), 26.

21 Hacohen.

22 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

23 Amanda Comack, “Closer Olson Enters O’s Hall of Fame,” Mlb.com, August 9, 2008.

24 John Eisenberg, “As Olson Goes, So Go the Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, September 10, 1989.

25 Ibid.

26 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

27 Hacohen.

28 Tom Boswell, “Arms Control Tough Task,” Washington Post, September 29, 1993.

29 Gregg Olson, email, January 11, 2015.

30 Comack.

31 Tim Kurkjian, “Between the Lines: What Streak?” Sports Illustrated, May14, 1990.

32 Hacohen.

33 Peter Schmuck, The Sporting News, January 3, 1994: 27.

34 Peter Pascarelli, “Baseball Report,” The Sporting News, January 24: 31.

35 Jeff Pearlman, “Inside Baseball: Gregg Olson Redux: Diamondback’s Comeback,” Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1998.

36 Gregg Olson, telephone conversation, January 26, 2015.

37 Los Angeles Times, “Gregg Olson, Braves Agree on One-Year Deal,” February 9, 1994 (from Associated Press).

38 Gregg Olson, telephone conversation, January 26, 2015.

39 Gregg Olson email, January 11, 2015.

40 Ibid.

41 Gregg Olson, telephone conversation, January 26, 2015.

42 Ibid.

43 Gregg Olson, telephone conversation, January 26, 2015.

44 Pearlman.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 David S. Cohen, “For Tommy Medica – One Hit, One Home Run Careers,”(thegoodphight.com), September 12, 2013. Note: At least five more members joined the club after Olson’s retirement.

48 baseball-almanac.com reports six bases-loaded intentional walks. The first was issued in 1881, the most recent in 2008.

49 Gregg Olson, “A Very Intentional Walk,” We Got to Play Baseball (Houston: Strategic Book Publishing, 2012), 107-110.

50 Pedro Gomez, “Arizona: White Named Team MVP,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1998: 70.

51 Jason Reid, “Olson Suffers a Setback,” Los Angeles Times, May 13, 2000.

52 Los Angeles Times, “Around the Majors,” July 4, 1999 (from the Associated Press).

53 Reid.

54 Chris Foster, “Olson Not Surprised at Being Cut Loose,” Los Angeles Times, June 24, 2001.

56 “The Master List of the 50 Greatest Sports Figures of the Century from Each of the 50 States,” Sports Illustrated, December 27, 1999.

Full Name

Greggory William Olson

Born

October 11, 1966 at Scribner, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.