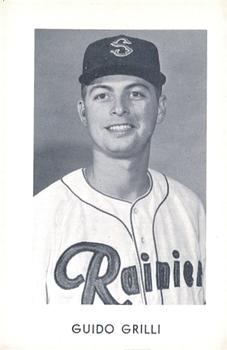

Guido Grilli

The first of three Grillis to play major-league baseball, Guido John Grilli had the briefest career of the three. In 1966 he was 0-1 for the Boston Red Sox and 0-1 for the Kansas City Athletics.

The first of three Grillis to play major-league baseball, Guido John Grilli had the briefest career of the three. In 1966 he was 0-1 for the Boston Red Sox and 0-1 for the Kansas City Athletics.

Grilli put in his time in the minor leagues. He was first signed by Red Sox scout George Digby in 1958, nearly eight years before he made the majors. He was a left-hander with a baseball scholarship on the University of Alabama freshman baseball team who grew to an even 6 feet tall, listed at 180 pounds, and had impressed Digby enough to attract a reported $25,000 bonus to sign for 1959,1 thus forfeiting his scholarship. 2

Guido John Grilli Jr. was born in Memphis on January 9, 1939. He knows of no family relation to the father-son pitchers Steve and Jason Grilli. His father Guido Sr. (1917-2008) had grown up working in his parent’s neighborhood grocery store. Drafted into the army soon after his son’s birth, he reportedly fought in France under Gen. George Patton.

Guido’s mother, Daisy [Ravarino] Grilli, was left to raise young Guido. After the war and her husband’s return, a daughter, Marie, was born. “Suffice it to say, we were a little poor,” said Grilli in a 2017 interview. “When my father came back from the war, he couldn’t find a job so we lived with my grandparents. His folks. My dad was building a house in Whitehaven, which was just outside of Memphis. He worked in the family grocery store. The store was doing pretty good — at least we ate well — until the larger stores, the supermarkets, came in. Then he worked for several food brokers. Knowing both sides of the counter, he was a pretty good salesman in terms of knowing what the grocers were experiencing and what they were looking for. He spent most of his life working in the food business with several food brokers.” One such was Memphis area food broker Bud Humphreys.3

“After high school, my sister found a job in Memphis working in a plant making Italian noodles – spaghetti and lots of other forms of pasta.”4

Guido went to St. Paul School and then Christian Brothers High School. His interest in baseball was kindled at an early age, no doubt inspired by his father.

After the war, Guido Sr. started pitching. He’d been a center fielder before the war, playing baseball. But his vision had changed while in military service and he couldn’t see the ball well enough from the outfield, so he stopped playing. “Another group of guys got together,” his son said, “and they were playing softball. He was a good athlete and they were trying to get him to play. He had never pitched before but they said, ‘We’ll teach you how to do it.’ Softball was big then, before the Grapefruit League. Every year they had a great team. I was batboy for them then. One year they won the world championship. That’s how great a team they were. They had some great players. Looking back after professional experience, I can see that the people I was keeping bats for…I liked them, but I had no idea how good they really were.

“My dad pitched softball and the games were like 1-0, 2-1 seven-inning games. Fast-pitch softball. I believe he went four or five games without walking a man. That was uncharacteristic for a lot of pitchers. The other guy, Bud Miller, was a lot faster, and stronger. A younger man. But he had a tendency to be a little wild. You would think my dad, who had excellent control as a softball pitcher, would have rubbed off on me. Not the case. Not so much.”

Guido Sr. “became one of the best pitchers in Memphis. He was part of one of the greatest pitching duels in competitive softball, teaming up in 1948 to pitch Standard Parts to runner-up in the Softball World Championships. He was inducted in the Memphis Park Commission Sports Hall of Fame on December 7, 1977. He enjoyed bowling and was a steady anchor man for his league bowling team, once bowling a near-perfect 300 game.”5

Guido Jr. says, “I learned a lot from just being batboy. I played baseball starting in about, I would guess, the fifth grade. I started pitching then, too, and probably threw a lot more curveballs than any human being has a right to.”

He pitched well enough that he got something of a baseball scholarship to high school. “There was a Christian Brothers High School. It was a high school and a junior college run by the Catholic Jesuits. It was probably the best school in Memphis at that time. Tuition was $300 a year at that time – quite a bit of money. My dad said, ‘I’m sorry. I can’t afford that.’ Brother Terence, who was the principal then, said, ‘How about $40 a year? And we’ll have him put books up in the library or clean a few blackboards after school?’ My father said, ‘I think he can handle that.’

“I had a high school scholarship to play baseball and basketball, and I ran some track. I didn’t play football because I didn’t weigh enough, and I had some problems with my knees. They said, ‘Son, if you want to play baseball or basketball or anything else, you better quit football. You’re going to be crippled before you get out of high school.’ We didn’t have a football field. We played on the school grounds. And on the end where the basketball court was, there were cobblestones. You get an idea how crude it was.”

Before signing with the Red Sox, Grilli spent a year at the University of Alabama on a full scholarship – even down to something like $10 a week for laundry. George Digby had offered some modest bonus money to sign with Boston, but at the time any player who accepted a bonus of $4,000 or more had to be kept on the major-league roster and thus typically lost a year’s development time. The rule was changed, and Grilli agreed to terms.

After signing with the Sox, Grilli was briefly with Alpine, Texas, for four games (0-1), but almost the full 1959 season was spent in Corning, New York, playing for manger Len Okrie and the Corning Cor-Sox of the Class-D New York-Penn League. He played in 28 games, all but five of them as a reliever, but managed to earn a fair number of decisions: he was 10-4 with a 2.83 ERA and 138 strikeouts in 108 innings of work.

In the offseasons, he continued his education, transferring to the University of Memphis where it was more affordable for him as an in-state student.

With Class-B Raleigh in the 1960 Carolina League, Grilli began to make a name for himself. The Greensboro Daily News reported on May 28 that “for the second time in recent weeks, Guido Grilli, Raleigh’s No. 1 southpaw, and Jim Bouton, Greensboro’s top right-hander, faced off in a duel of aces. For the second time, Grilli came off the winner.”6 A week later, the newspaper notified readers, “Guido Grilli, the young pitching star of Raleigh’s Caps, says his name has a ‘I’ on the end, not an ‘e’ as it has been spelled most of the year.”7 Some newspaper articles referred to him as “bespectacled,” due to the eyeglasses he wore. A couple of days later, he was leading the Greensboro Yanks, 3-0, in a game that was called on account of rain. Sportswriter Smith Barber noted him as “a Yankee nemesis this summer…tougher than ever.”8 That phrase may have gladdened hearts in Red Sox scouting circles. He pitched in the Carolina League All-Star Game.

In early July, Grilli was promoted to Class-A Allentown (Eastern League). He’d been 7-2 (2.63) for Raleigh. With Allentown, he was 9-5 (3.31).

In 1961 he was asked to play Single-A ball again, this town for the Johnstown Red Sox in Pennsylvania; the Red Sox had shifted from Allentown to Johnstown. He wasn’t content with the assignment and wrote to scouting director Neil Mahoney pleading his case for a better assignment. Mahoney took a chance on him and promoted him to the Seattle Rainiers in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, with a bit of a pay raise and a promise of more if he proved himself and stuck past the first 30 days.9 Seattle was overstocked with pitchers, though, and Grilli was perhaps not ready. He pitched five innings in four games without a decision but with a 7.20 ERA. He was sent to Johnstown. There he worked primarily as a starter (in 19 of his 21 games); his year-end record was 8-9 with a 4.50 ERA.

In 1962, Grilli was among the pitchers the Red Sox brought to early spring training at a minor-league camp run by Johnny Pesky at Ocala. He was back in the Eastern League again, this time pitching for the York White Roses (the Red Sox had, for the third year in a row, moved their franchise – which they did again, to Reading in 1963). With York, he beat the Springfield Giants on April 28 for his first win of the season, holding them to three hits and striking out 13. On August 13, against the Giants again, he had a no-hitter through 8 1/3 innings before winning, 2-1. Aside from the high points, there were pedestrian efforts as well and on the season he was 10-12 (4.47), starting in 23 of his 28 games.

Grilli put in military service time in 1962 and 1963, with the United States Army. “Six months of active duty and then 4 or 4 ½ years of active reserve. When I went it to do my active duty — my six months of basic training – it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis and we weren’t sure when we got out of the truck if we were going to go to the rifle range or to Cuba.” While on leave for Christmas, he married – the day after Christmas – to Adele Wolf. “I worked that in, between the basic training.” Some 55 years later, the two remain married.

When the Red Sox franchise moved to Reading in 1963, Grilli moved with them. He had 10 starts and was 4-4 with a 2.16 ERA when, in the second half of June, he finally got his promotion to Triple-A Seattle. Pitching at the higher level appears to have been more challenging. His ERA climbed to 5.67 in 13 starts and seven relief stints for the last-place Rainiers.

He spent the full ’64 season in Seattle. The team did better and he was a part of that, with a 3.65 ERA, though his record was a losing one (7-10).

During these times, instruction in the minor leagues, particularly for pitchers, was still often hit and miss. “In Seattle in ’64, I went back to my old way of throwing the curveball but I couldn’t get anybody to play catch with me because I’d throw one over their heads or bounce it in front of them. It took a little while to get the timing and rhythm back to throw a good hard curveball with plenty of spin and rotation. A nice changeup curveball is good every once in a while, but that’s not what you want in a curveball for your bread and butter.

“I told myself, I’ve played enough years now, I’m going to go back to my other curveball and see what happens. Well, the first half of the season was not too good, and then I changed and I finally started throwing it in the game. I think the first game that I pitched against San Diego in the Pacific Coast League [he met some of the Padres after the game] and they said, ‘Where’d you get that curve ball?’ I said, ‘That’s the way I used to throw my curveball,’ and they said, ‘I hate to say it but you need to stick with that one.’ Deron Johnson, a right-handed hitter, said, ‘That’s the best curveball I’ve seen all year.’ I said, ‘Thank you very much.’”

Between the 1964 and 1965 seasons, the Red Sox moved their Triple-A team from Seattle to Toronto.

The first mention of Grilli in the Boston Globe appears to have come in May 1965 when pitcher Bob “Ach” Duliba mentioned his work in Toronto. Commenting on a number of players, he said, “Guido Grilli, a left-handed reliever, has been doing well up there.”10 He had indeed run up a string of 15 scoreless innings of relief and an ERA of 0.39 when the Boston Traveler weighed in with a mention on June 5.

Grilli recalled the season. “Well, in ’64, with Seattle, I told myself, ‘I’ve played long enough. I’m going to play one more year. If I have a good year, I’ll come back. If I have a bad or just a mediocre year, I’m going to go home and finish college and join the LP league – as we used to call it, the lunch pail league.’

“Dick Williams was the manager, and a lot of people didn’t care for him. He said, ‘I want you to go down to the bullpen and pitch relief.’ I said, ‘Dick, I’ve never really pitched relief. I’ve done some middle-inning work but never as a closer or a late-inning guy.’ He said, ‘Well, Bob Duliba’s down there and Bob’s a good man. He can help you.’ Boy, he did.”

“The first time I talked to him he said, ‘You have to warm up a little faster.’ I said, ‘Bob, it takes me 15 minutes to warm up.’ He said, ‘Well, you won’t have that much time coming out of the bullpen.’ He said, ‘I want you to throw fastballs in a different way, too. You’re been throwing cross-seam fastballs a lot. I want to see you pitch some off the skin or in between the loop. That’ll give you a good sinker. If you can learn to throw 10 out of 10 low and away, when you come in even if it’s against a right-hander and you have that ball sink down low and away, if they’re trying to pull the ball, that’s a perfect pitch for a double play.’ I took everything he said to heart, because I’d seen him pitch before and while he was not in his best years, you could tell that he knew how to pitch.” And Grilli had his best season of professional baseball.

When Grilli saw Duliba in Boston for the 100th anniversary celebration of Fenway Park, he told him, “I’d like to thank you again. I never thought I could do it.”11

Grilli’s full 1965 season was spent with Toronto again. He worked exclusively in relief, pitching in 58 games, and struck out 90 batters in 90 innings. He posted a record of 8-2 (2.30), boosted by what a Sporting News writer called “an intimidating curve ball.”12 The 58 appearances tied for tops in the league. After the Toronto season was over, manager Dick Williams listed Grilli with three other prospects who he believed would make the Boston Red Sox in 1966. Pete Charton, Joe Foy, and Gerry Herron were the other three.13 A poll of International League managers granted Grilli recognition as the pitcher with the best curveball in the league.14 The Maple Leafs won the Governors’ Cup league playoffs. The Red Sox offered Grilli a big-league contract.

Grilli impressed Boston manager Billy Herman, not allowing a run in his first 11 innings, and made the team out of spring training. He enjoyed his major-league debut on Opening Day at Fenway Park, April 12, 1966. In the top of the ninth, in a game the Red Sox were leading 4-3, and with runners on second and third and one out, Grilli replaced erstwhile ace reliever Dick Radatz. He was brought in as a lefty to face left-handed-hitting Curt Blefary but walked him. He was removed for a righty, and the Orioles tied the game shortly afterward, winning it in the 13th.

On April 15, he pitched again with two runners on base, and this time walked the only batter he faced. That runner scored, the first run charged against him.

He recorded his first out on April 17, striking out the first batter he faced. He gave up a walk and a single the next inning but worked his way out of the jam. His one and only decision with the Red Sox came on April 27 when he took over in the top of the fifth in a game the White Sox were winning, 5-3. He got the final two outs in the fifth and he singled in the bottom of the fifth, his first major-league at-bat, scoring on a Yaz double to tie the score. It was his game now. He got through the sixth, but in the top of the seventh walked two batters and was touched for a run-scoring single that proved to be the winning hit.

Grilli appeared in two games in May, for a total of one inning. At this point he was 0-1 with an ERA of 7.71. He was demoted to Toronto, where he pitched very well (4-0, 1.89). That was good enough to be of some interest to the Kansas City Athletics, who acquired him as part of a six-player swap on June 13. The A’s got Jim Gosger and Ken Sanders, too, sending Rollie Sheldon, Jose Tartabull, and John Wyatt to Boston.

Grilli joined Kansas City and got into his first games on June 16, when he worked briefly in both halves of a doubleheader in Chicago. He only gave up one run in his first eight appearances, but then got hammered by the Orioles for five runs on June 30. On July 6, this time in Baltimore, he was hit for seven runs – five of them earned. In neither game did he suffer the loss. The one decision – a loss – that he had for the Athletics came against the Yankees on July 14. He walked the one batter he faced (Joe Pepitone), and Pepitone came around to score the run that broke a tie .

Two days later, he worked two-thirds of an inning against the Yanks, but was then sent to Vancouver on July 18.

He’d appeared in 16 games for the Athletics, with an ERA of 6.89. He was credited with one save, on July 3, though it would not be a save by today’s standards. Kansas City had a 10-4 lead over the Detroit Tigers and he pitched a scoreless ninth. At least that was a game his team won. In the 22 major-league games in which he appeared, the team for which he pitched only won two. That was only deemed his fault twice (his two losses), but it had to feel discouraging having taken part in the game but rarely feeling good about those games.

As a batter, the single he had hit on April 27 was his only big-league base hit. He only batted one other time, striking out later in that same game. His lifetime .500 batting average still stands.

As a fielder, he was less successful. Of the five chances he had, he flubbed two of them, leaving him with a .600 career fielding percentage.

Back in the Pacific Coast League, Grilli worked in 15 games for Vancouver, all in relief. He was 0-1, 4.74.

“Why did I quit? After the year I had with Dick Williams, I went to spring training and pitched 13 innings and gave up three hits and no runs. Struck out Roger Maris. Mickey Mantle didn’t want to swing against some wild left-hander that nobody knows. I went to Boston and it rained a lot and it snowed a bit and I didn’t get to pitch. When I finally did get to pitch, I couldn’t get the ball where I wanted to.

“Then I got traded to Kansas City. People ask me, ‘Why did you quit?’ I say, ‘Well, I went from the best organization, the Red Sox, to the worst.’ Charlie Finley with the mule. The softball-looking uniform….

“Dick Williams, when they sent me down from Boston to Toronto [in 1966], he said, ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Well, I didn’t get to pitch, and when I did pitch, I didn’t know where it was going. He said, ‘Go back down to the bullpen.’ Then I was 4-0, because I picked up where I left off the last year because I got to pitch. Same thing in Kansas City. Every time they had a chance to win a ballgame, Jack Aker was up and throwing about the best sinker I ever saw and his arm was about to fall off. But anyhow that’s long ago.

“If I didn’t get to pitch, when I got in a game it wasn’t on the black anymore. It was too much on the plate – down the middle or whatever.”

It’s quite possible that throwing as many curveballs as he did, from such a young age, may have hindered his chances to extend his career. “When I came back from playing baseball, I coached a few teams. Helped a couple of guys from time to time. And I always stressed, don’t throw any curveballs until maybe 14, 15, or even 16 years old and your bones are formed. I had lots of bone chips in my elbow. If you talk to other guys who pitched quite a bit, they’ll tell you the same thing. It comes with the territory. If you push the curveballs too early, I think it’s really hard on your elbow.”

Grilli finished his degree at the University of Memphis. Start to finish, one semester per year, it had taken him 10 years. “Lost two semesters, one due to basic training and another one they called me for my 15 days’ active duty – ‘summer camp,’ they used to call it – in January. Arrived at Fort Knox, Kentucky, MOS #131 armored tank crewman, is what I was after basic training. There was a foot of snow on the ground. I was a week away from taking my final exams. Couldn’t get them to change it. That left kind of a bad taste in my mouth for the Army.”

“On the way to finishing, I loaded a lot of trucks for Roadway Express and a couple of other companies. After playing professional baseball for eight years and living out of a suitcase more than half of the time, I said, ‘I’m not going with IBM or General Motors or anybody else that would move me after a year or two.’ They would shuffle people around. I said, ‘I’ll find a place that has their home base here in Memphis if I can.’ I worked for Holiday Inns for nearly 24 years.

“The British corporation Bass PLC – which owned a few hotels in Europe and the UK – they bought some interest in some Holiday Inn franchises, and then the original Holiday Inns got sold to Bass. They said, ‘We’re not going to move the company.’ Well, two years later, they said they were moving it to Atlanta. I didn’t want to go to Atlanta. I spent almost five months training my replacement, flying down to Atlanta, getting on the plane Monday and coming home on Friday. Finally, I said, ‘Hey, I’ve got to get on with my life here.’

“My wife’s mother had a place in Batesville, Arkansas. She had lots of friends and not a single relative. When she retired, it just so happened that I was leaving Holiday Inns and decided to come here. I think it’s the best decision I ever made. I love it over here. The river’s the backyard. I’m out in the sticks. No traffic. People would ask, ‘How big a town is it, Locust Grove?’ I don’t know, three or four or five, six hundred. I have no idea. One traffic light between my house and 14 miles to Batesville where I work. I got a job at a construction company handling their office and doing their accounting. Pretty much what I did with Holiday Inns. I did the budgeting and forecasting for one of their divisions. I enjoyed it while I was there.”

Grilli still keeps a hand in, helping his daughter with her business. “She emails me the menus and I’ve created a database of all the menus they’ve had over the years. I’ve got 15 to 20,000 records. She sends them to me and I plug them in and price them and I send them back to her. She looks at them and makes some adjustments, but it saves her time. I do a lot of other stuff similar to that. Yeah, it’s good.”

Guido and Adele Grilli live in the small community of Locust Grove, Arkansas. They had one daughter and then a son. Their daughter has a catering business in Memphis, about 130 miles away. “We live pretty much in the middle of Arkansas. North-central, I guess you’d say. She loved to cook so she started a business. Has owned a restaurant. And is now strictly into catering. She handles a company’s lunch, Monday through Friday. Since 2003 or 2002.

“She was born in ’66 and our son was born in ’70. He was a pretty good athlete, too, mostly in soccer. He’s a musician. Was a musician. They had a band all through high school. Believe it or not, some of the guys are still playing together periodically in Memphis. He started in with the drums, right on the other side of the wall from my recliner. It wasn’t much fun then. He started out with the violin, with the Suzuki method. Then he graduated to more of a guitar. He sings and he plays guitar in the band.

“But he’s a computer guy. He worked for FedEx for over 10 years. Since he moved to Arkansas, he’s working for another company now but doing essentially the same thing. Network stuff. He gradually taught himself how to repair them and took all the Microsoft programs that they offer.

“At first, I got the impression that he was trying to play baseball for my sake. ‘You don’t need to do that,’ I said. My parents never pushed me into anything, but they supported me. That’s the best thing I think a parent can do for a kid.”

Last revised: January 23, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Grilli’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 UPI, “Sox Give 25-G Bonus to Young Southpaw,” Boston American, July 22, 1958: 9.

2 Hy Zimmerman, “Grilli Came to Rainiers By Mail,” Seattle Daily Times, April 27, 1961: 32.

3 https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=31956803

4 Author interview with Guido Grilli on November 9, 2017. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations directly attributed to Guido Grilli come from this interview.

5 Ibid. The softball team may have been, as indicated, been runner-up in the world championship tournament, not the ultimate champion.

6 Moses Crutchfield, “Raleigh Triumphs 3-1 Over Greensboro Yanks,” Greensboro Daily News, May 28, 1960: 12.

7 Moses Crutchfield, “Indians Turn Red Sox; Yanks See Gate Pickup,” Greensboro Daily News, June 5, 1960: 31.

8 Smith Barber, “Yanks Now Meet Raleigh in Two – No. 1 At Stake,” Greensboro Daily News, June 7, 1960: 14.

9 Hy Zimmerman, “Grilli Came to Rainiers By Mail,” Seattle Daily Times, April 27, 1961: 32.

10 Hy Hurwitz, “Duliba Joins Sox, Hails Play of Horton, Gosger,” Boston Globe, May 29, 1965: 18.

11 Author interview with Guido Grilli.

12 Neil MacCarl, “Maple Leafs Waltz to Rhythm of Sinks, Charton and Herron,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1965: 31.

13 Herb Ralby, “Toronto Players Seen Great Help to Sox,” Boston Globe, September 30, 1965: 50.

14 Neil MacCarl, “Jets’ Blass Edges Teammates For Int Tag as Top Hill Prize,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1965: 34.

Full Name

Guido John Grilli

Born

January 9, 1939 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.