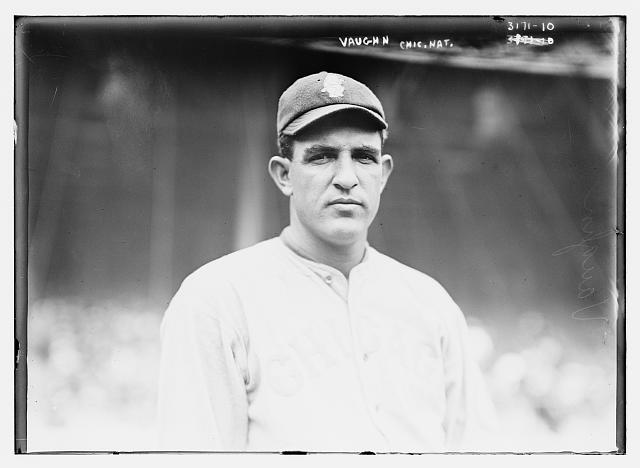

Hippo Vaughn

Some ballplayers are defined by one moment. Jim “Hippo” Vaughn was such a player. Mentioning his name evokes a knee-jerk reaction from a knowledgeable fan: “Oh, yes, he threw the double no-hitter with Fred Toney in 1917.” This is unfortunate because that game is but one in the career of a pitcher whose overall performance was excellent. From 1914 to 1920, Vaughn was the best lefty in the National League if not in the game, but his short career leaves him just this side of the Hall of Fame.

Some ballplayers are defined by one moment. Jim “Hippo” Vaughn was such a player. Mentioning his name evokes a knee-jerk reaction from a knowledgeable fan: “Oh, yes, he threw the double no-hitter with Fred Toney in 1917.” This is unfortunate because that game is but one in the career of a pitcher whose overall performance was excellent. From 1914 to 1920, Vaughn was the best lefty in the National League if not in the game, but his short career leaves him just this side of the Hall of Fame.

Born April 9, 1888, in Weatherford, Texas, due west of Fort Worth, Jim was one of eight children of Josephine and Thomas Vaughn, a stonemason. Finishing school in Weatherford, he began pitching professionally with Temple in the Texas League in 1906. He spent 1907 at Corsicana in the North Texas League, then moved on to Hot Springs in the Arkansas State League, going 9-1 and getting a shot with the New York Highlanders. He debuted with New York on June 19, 1908. His work for 2⅓ innings in two games showed some wildness with five walks, and he finished the season with Scranton of the New York State League, his 2-4 record offset by six complete games, a shutout, and a fine 2.39 ERA. Vaughn began 1909 with Macon in the South Atlantic League, where he threw a no-hitter, had a 1.95 ERA, suffered sparse run support, and wound up 9-16. He moved to Louisville in the American Association that same year, threw another no-hitter, and went 8-1 with an ERA of 2.05.

Vaughn rejoined the Highlanders at spring training in 1910 and so impressed manager George Stallings that he gave Vaughn the opening day assignment. Lyle Spatz notes in New York Yankee Openers that at twenty-two Vaughn was, and remains, the youngest pitcher ever to start the opening game for the Yankees. He faced the Boston Red Sox and Eddie Cicotte on April 14 at Hilltop Park. After a rough start in which he gave up three runs in the first three innings and another in the fifth, Vaughn settled down, and he and Joe Wood (relieving Cicotte) pitched shutout ball until the game was called on account of darkness after 14 innings with the score tied 4-4. The game was an indication of good things to come. Overshadowed by Russ Ford‘s brilliant rookie season of 26-6 with a 1.65 ERA, Vaughn went 13-11 for the season with an excellent 1.83 ERA, 18 complete games, and five shutouts.

Hal Chase became manager of the Highlanders late in 1910 and returned for the full 1911 season. Chase, like Stallings before him, was impressed with Vaughn and selected him for the April 12 opener in Philadelphia against Chief Bender. Both men pitched beautifully, with Vaughn winning a 2-1 decision and helping himself with a single. The rest of the season was a disappointment as Vaughn finished up 8-10 with a 4.39 ERA.

Vaughn got into the opener in New York on April 12, 1912, against Boston and Joe Wood, recording the last two outs in the ninth inning after Ray Caldwell surrendered four runs, giving Boston a 5-3 win. From that point on, Vaughn was 2-8 with an ERA of 5.14 and a shutout, until June 26, when New York sold him to Washington for the waiver price. He did better in Washington, going 4-3 with a 2.89 ERA. Washington sold him to Kansas City of the American Association, where he finished the year weakly, 2-3 while giving up over five runs a game.

The 1913 season found Vaughn back in Kansas City, where he recovered his form with a record of 14-13 and an ERA of 2.05 along with a no-hitter against Toledo on June 23. The Chicago Cubs took a chance on him that paid off immediately. He finished the season 5-1 with six complete games, two shutouts, and an ERA of 1.45.

Sometimes a player, a team, and a city come together almost magically. Such was the case with Vaughn, the Cubs, and Chicago. He had found a home.

Vaughn’s 1914 season was pretty much what the next six seasons would be: 21-13 with a 2.05 ERA. Indeed, looking at Vaughn’s numbers during this period is like looking at Warren Spahn‘s career over any half-dozen years — 17 to 23 wins, a high percentage of complete games, 260 to 300 innings pitched, good control, a decent number of strikeouts, and an ERA below the league average. Of course, Spahn did it more than twice as long. Vaughn’s 1915 showing was a bit off, 20-12 but with an ERA of 2.87 that was the worst of his prime years and the only season that he had fewer complete games (18) than wins. He slipped to 17-15 in 1916 but brought his ERA down to 2.20. As further proof of his consistency, he pitched four shutouts each season.

Amid these good times, Vaughn married Edna Coburn DeBold on February 11, 1916. On a less happy note, sometime during these years he acquired the nickname “Hippo” that followed him all his life. Vaughn was a large man, about six-foot-four, with most references listing him between 215 and 230 pounds. There is some evidence that he weighed close to three hundred pounds later in his career, and his slow, side-to-side, lumbering gait didn’t help. What Vaughn thought of the nickname isn’t known.

From 1914 to 1916, Vaughn was a very fine pitcher. From 1917 to 1919, he was a great one. The only National League lefthanders to put together a better string of seasons would be Carl Hubbell from 1933 to 1937 and Sandy Koufax from 1962 to 1966.

In 1917 Vaughn established himself as a dominant pitcher. He started a career-high 38 games, completed 27 (also his best, equaling it in 1918), struck out 195 (career best), went 23-13, and topped it off with a sparkling 2.01 ERA.

The highlight of the year came at Weeghman Park on May 2, when he and Fred Toney of Cincinnati both threw no-hitters through nine innings. Vaughn faced the minimum 27 batters, one baserunner caught stealing and two others erased on double plays. He struck out ten while walking two and allowing only Greasy Neale to hit a ball out of the infield. It all unraveled in the tenth. With one out, Larry Kopf singled to right. Neale flied to center for the second out. Then, in a moment of irony that occurs only in baseball, Hal Chase hit a hard liner that Cy Williams couldn’t hold. Kopf moved to third on the play. Chase stole second. Jim Thorpe then hit a slow roller toward third that catcher Art Wilson and Vaughn both chased. Vaughn caught up with the ball and seeing that he couldn’t get Thorpe at first, threw home to Wilson to catch Kopf trying to score from third. Wilson still had his back turned, and Vaughn’s throw hit him on the shoulder. Kopf scored easily, and Chase, thinking the ball had bounced far enough away, tried to score, but Wilson recovered the ball and tagged him for the third out. That was the final score, 1-0, as Toney retired the Cubs in the bottom of the inning. Christy Mathewson, who was managing the Reds and knew a bit about pitching, called it the greatest pitching performance he’d ever seen. Vaughn, for understandable reasons, didn’t like to talk about the game but graciously discussed it with Hal Totten for John P. Carmichael’s My Greatest Day in Baseball (1945).

The 1918 season began with Chicago in high hopes. The White Sox had beaten the Giants in the World Series the fall before, and Cubs fans figured it was their turn. They had good reason. Vaughn was coming off a great season, and the Cubs had acquired none other than Grover Cleveland Alexander from Philadelphia. Alexander started off well, but, as the Philadelphia front office cynically gambled would happen, was drafted into the army and lost for the season. Vaughn responded magnificently.

He started off by beating the Cardinals on April 18, helping himself with two hits and scoring two runs. On April 24 in the Cubs’ home opener, Vaughn pitched a 2-0, one-hit masterpiece against the same Cardinals (Rogers Hornsby got the only hit in the second inning), striking out six and walking just two while letting no one get to second base. He came down with the flu in June, but the setback was temporary. Vaughn beat the Cardinals, 1-0, on another one-hitter on June 26. He shut out Cincinnati, 2-0, on June 29, and made the day a doubleheader sweep, having welcomed James Leslie Vaughn Jr., the Vaughns’ only child, that morning. Vaughn was unbeatable for most of the season, another example being his 1-0 win over the Giants as he drove in the only run of the game with a single in the twelfth inning.

The season was shortened to 140 games and ended on September 2 as the government enacted a “Fight or Work” decree in support of the war effort. Vaughn tailed off a bit as the season wound down, but his exceptional work had propelled the Cubs to the pennant 10.5 games ahead of the Giants. Vaughn captured the pitchers’ Triple Crown, leading the National League in wins with 22 (against just 10 losses), strikeouts with 148, and ERA at 1.74. Equally impressive is his eight shutouts, which stood as the National League record for southpaws (tied with Lefty Leifield of Pittsburgh in 1906 and teammate Lefty Tyler in 1918) until Hubbell threw 10 in 1933.

Vaughn didn’t let up in the Series against the Red Sox, but he had little luck against three excellent pitchers. Fellow lefty Babe Ruth beat Vaughn, 1-0, in Game One. Carl Mays, who would win over two hundred games in his career, took Game Three from Vaughn, 2-1. Vaughn then shut out another two-hundred-game winner, Sad Sam Jones, 3-0, in Game Five. His brilliant work included three complete games, three earned runs, an ERA of 1.00 — and a 1-2 record. The Cubs lost the Series in six games.

Vaughn essentially duplicated his 1918 effort the next season, going 21-14 with 141 strikeouts, his usual four shutouts, and a 1.79 ERA. The Cubs, however, went 75-65 and slipped to third place. In hindsight, the 1920 season showed some signs that not all was well. The Cubs continued to decline, going 75-79 and finishing fifth, so Vaughn’s 19-16 record looked good in comparison. However, his ERA was a high (for him) 2.54, though near his career ERA of 2.49. His strikeouts fell to 131, slightly off his usual performance. What might have raised alarms was Vaughn’s giving up 301 hits in 301 innings, the first time he had surrendered a hit an inning since 1912. Nevertheless, no one thought the end was near.

The 1921 season was a flameout as Vaughn went 3-11 with an ERA of 6.01. His demise as a major league pitcher came in a 6-5 loss to the Giants at the Polo Grounds on July 9. In the bottom of the fourth inning with one out Giant catcher Frank (Pancho) Snyder rocked Vaughn for a grand slam home run. The next batter, pitcher Phil Douglas, applied the coup de grace with the first of his two major league homers. Manager Johnny Evers pulled Vaughn from the game, and that was the end.

What followed was a comedy of errors to all but the participants. The New York Times reported on July 11 that neither Evers nor anyone from the Cubs organization had seen Vaughn since the game, noting that he would draw a suspension if and when he returned to the club. Also in trouble was catcher Bob O’Farrell, who had been suspended for not following team rules. The Chicago Daily Tribune, having called Vaughn “A.W.O.L.” on July 11, noted on July 15 that he was back in Chicago. The Times followed up on July 20, saying that Cubs president William Veeck would trade Vaughn if he could get appropriate value for him.

Never to be outdone, The Sporting News on July 21 defended Evers for suspending Vaughn in a headline and two sublines lest anyone miss the point: “EVERS FORCED INTO USING MAILED FISTS”; “DOES NOT MEAN GENERAL TROUBLE ON CUBS HOWEVER”; and “John Only Asks Players to Hustle and Obey Orders and If They Don’t They Must Suffer.”

In the second paragraph of the article the unnamed writer goes after Vaughn: “Vaughn is not the easiest player in the world to handle. Although possessed of speed and nerves, he is not the smartest twirler in the game. His tendency to pitch wrong to batters is what has caused most of his trouble with managers.” This writer seems to contradict Vaughn’s knowledgeable teammate Pete Alexander: “Big Jim Vaughn used to pitch the particular kind of ball a batter liked best just to show him that he couldn’t hit it. Nothing pleased him better than to strike a man out pitching to his strength.” Vaughn, for his part, told F. C. Lane that he did this only occasionally, that he usually pitched to a hitter’s weakness but switched gears to keep a hitter off-balance. Indeed, Vaughn’s comments to Lane indicate that he knew exactly what he was doing: “That isn’t to say, of course, that every ball pitched is to the batter’s weakness. If this were so the batter would always know what was coming and in time would break himself of that weakness. But it does follow that in the main the pitcher tries to give the batter balls that he is known to have difficulty in meeting.” Actually, everybody involved may have been right. That is, if Vaughn had lost something off his fastball, the approach Alexander described would have been courting disaster.

On August 1, the Tribune reported that Vaughn, “under indefinite suspension for failure to keep in fighting trim,” would probably wind up pitching for the Beloit Fairies, a semi-pro team owned by the Fairbanks-Morse “company.” A week later, on August 8, the Tribune noted that Evers having been fired, new manager Bill Killefer and Cub president Veeck were ready to reinstate Vaughn pending approval from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Ignoring Killefer and Veeck, Landis suspended Vaughn for at least the remainder of the season. The Tribune of August 10 summarized Landis’ unique logic in suspending Vaughn, who had reason to believe he was finished as far the Cubs were concerned: “The judge in suspending the big pitcher declared Vaughn, after notification of his suspension by the Cubs, had signed a three year contract to pitch for the Fairbanks-Morse semi-pro nine of Beloit, Wis. . . . In so doing the judge declared Vaughn deliberately ignored his contract with the Cubs and aligned himself with an outlaw team which harbors ineligible players and plays outlaw clubs.” The Tribune summed matters up through understatement the next day: “The affair has been bungled.” And conveniently forgetting everything it had said on Evers’ behalf at Vaughn’s expense, The Sporting News on August 11 and 18 suggested that the Cubs’ fall was primarily Evers’ fault, that the players had had their fill of his “Old Crabbing Habits” (August 11) and were delighted to have Killefer at the helm!

As if all this weren’t enough, The Times (October 14) noted that Vaughn’s wife telephoned the Chicago police from Kenosha, where they had moved, that Jim had “been mysteriously missing since last Sunday [October 9].” She wanted the police to look for him because their “three-year-old son, ‘Little Hippo,’ she said, is ill and crying for his father.” The piece concludes: “A year ago Mrs. Vaughn sued ‘Hippo’ for divorce. While they were at outs her father, Harry Debold, stabbed him in a quarrel in a Kenosha saloon. The Vaughns were reconciled subsequently.” Clearly, 1921 wasn’t Vaughn’s favorite year.

Several explanations arise, but none has ever been confirmed. The most common is that Vaughn had a sore arm, tempting given his age and the possibility that his weight had caught up with him. Too, the Cubs fell precipitously, going 65-89 and landing in seventh place under their new manager, Johnny Evers. Evers’ manic personality had helped the Cubs enormously in the glory years from 1906 to 1910 and the Braves in 1914, but it didn’t sit well when he became a manager as the team went 41-55 under him. Vaughn, a quiet professional who went about his business, seems to have found Evers particularly annoying and left the team late in June, official reports saying he had a sore arm. As for the Cubs, they did no better under new manager Bill Killefer, Alexander’s catcher in Philadelphia, going 23-34.

The explanation that Vaughn had arm trouble loses a little credence in light of his performance with Beloit in the Midwest League-either an independent or even outlaw league, or most likely a semi-pro league-where he compiled an 11-1 record with 99 strikeouts against nine walks and an ERA approximated at 2.01. Of course, the Midwest League wasn’t the National League, so a pitcher with Vaughn’s skill and experience could likely have dominated over inferior talent even with a sore arm. In any case, reported the Tribune on January 13, 1922, the Beloit Fairies liked Vaughn well enough to give him a three-year contract. Vaughn would pitch in various minor and semi-pro leagues, mostly with Beloit, the Logan Squares of Chicago, and the Chicago Mills until 1937, when he was 49.

Altogether, Vaughn went 223-145 in minor league and semi-pro ball, most of those decisions coming after he left the Cubs. With his major league record of 178-137, Vaughn is one of the very few pitchers credited with four hundred or more wins. Cy Young and Walter Johnson, of course, got theirs in the majors. The others — Alexander, Joe McGinnity, Kid Nichols, and Spahn — while getting some wins outside the big leagues still got the majority in the majors. It’s still an exclusive club.

Vaughn considered making a comeback with the Cubs, but it never worked out. He pitched some batting practice, and that was it. Away from baseball, he was an assembler for a refrigeration products company. He spent his life in Chicago, dying May 29, 1966.

Vaughn is clearly the best lefthander the Cubs have ever had. He threw hard, had good control, gave up less than a hit an inning, and was stingy with runs. His 151 wins is miles ahead of Larry French‘s 95. He won twenty games five times in seven years. No other Cub southpaw did it more than twice (Jake Weimer in 1903 and 1904). No Cub lefty achieved it after Vaughn in 1919 until Dick Ellsworth did so in 1963. No one’s done it since. Vaughn was an excellent pitcher for seven years and a great one for some of that time, but except for one day in 1917, he’s pretty much forgotten.

Hubbell, Spahn, Koufax, and Steve Carlton are the four greatest southpaws in National League history and are enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Vaughn just didn’t pitch as long as Hubbell, Spahn, and Carlton; he wasn’t as overpowering as Koufax was during his five-year reign or Carlton was during his big seasons. He’s not in Cooperstown and isn’t likely to be, having never received a vote, but he’s not very far behind them. Nor is it clear who stands between Vaughn and the titans. Tom Glavine is a possibility, but he is still active and may eventually establish himself in the highest echelon. Jim Vaughn’s case shows that in baseball the difference between excellence and greatness is often the smallest matter of degree.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

I am especially indebted and grateful to Terry Simpkins for kindly pointing out and helping me correct some errors about the end of Vaughn’s major league career.

Ditmar, Joseph J. Baseball Records Registry: The Best and Worst Single-Day Performances & the Stories Behind Them. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997.

Hoie, Bob, Carlos Bauer, et al, eds. The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players. San Diego and San Marino: Baseball Press Books, 1998.

James Leslie (Hippo) Vaughn files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Lane, F. C. Batting. Reprint. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001.

Santo, Ron, and Phil Pepe. Few and Chosen: Defining Cubs Greatness Across the

Eras. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005.

Spatz, Lyle. New York Yankee Openers: An Opening Day History of Baseball’s Most Famous Team, 1903-1996. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997.

_____. Yankees Coming, Yankees Going: New York Yankee Player Transactions, 1903 Through 1999. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000.

Vaughn, Hippo, with Hal Totten. In John P. Carmichael, ed. My Greatest Day in Baseball. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1945. Reissued Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Wilbert, Warren, and William Hageman. Chicago Cubs: Seasons at the Summit. The 50 Greatest Individual Seasons. Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1997.

Full Name

James Leslie Vaughn

Born

April 9, 1888 at Weatherford, TX (USA)

Died

May 29, 1966 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.