Irv Young

Irving Melrose “Cy the Second”/“Young Cy” Young was born on July 21, 1877, and raised in Columbia Falls, Washington County, Maine, in the state’s “Downeast” area. His father, William Wallace Young (1844-1911), worked as a farmer at the time of the 1880 census, and he and his wife, (the former Syldania French), raised six children — Rowland, Orie, Minerva, Sewall, Mabel, and their youngest, Irving.

Around 1894, William, Syldania, and family moved to Concord, New Hampshire, where William took a position as a woodworker in a car shop, helping make railroad cars. At the time of the 1900 census, Irving was listed as a fireman on the Boston & Maine Railroad, perhaps better work than serving as a lumberjack in the Maine woods.1 Although he worked 60 hours a week on the railroad, Irv managed to find time to pitch for the YMCA and other local amateur clubs on weekends. He later took up work at a hosiery mill in Concord.2 In 1904, at the rather advanced age of 26, Irv turned pro, joining Concord in the New England League.3 There the young left-hander won 18 games (losing 14) and caught the eye of scout Billy Hamilton. Hamilton strongly recommended him to the Boston Beaneaters (the National League team later known as the Braves), who bought his contract for $500. (There was a brief problem that cropped up in June 1905, when the Concord club complained that it had yet to receive its final $250, but that was apparently resolved quickly enough.)4

Young was 5-feet-10 and listed at 170 pounds.

At age 27 in 1905, Irv Young had his shot at the major leagues. He made the most of it. He led the league in three categories: most innings pitched (378), most games started (42), and most complete games (41). He was second in the league in shutouts with seven (only the immortal Christy Mathewson, with eight, had more) and fifth in strikeouts. His earned-run average was 2.90, respectable in any league. And he won 20 games. Yet, alas, he lost 21. But let’s discount that. Irv Young, in playing for manager Fred Tenney and the 1905 Beaneaters, was playing for one of the more inept teams in baseball’s long history. Let’s concentrate — and celebrate — on the fact that he won 20 games. As a rookie.

All these years later, Young’s 1905 total of 378 innings pitched and 41 complete games are still major-league records for a rookie. Needless to say, in this day and age of almost incessant relief pitching, they are records that will most likely last forever. And that’s a long, long time. Irv’s total of seven shutouts was also a long-standing rookie high, tied by Pete Alexander in 1911 and by Jerry Koosman in 1968, and eventually broken by Fernando Valenzuela in 1981.

Young’s banner season started well. He appeared in relief, pitching the final four innings of the Beaneaters’ April 14 Opening Day game before a crowd of 40,000 at the Polo Grounds. And he pitched effectively, holding the soon-to-become World Champion McGrawmen to but four hits and two runs. He also knocked in Boston’s only run in the eighth inning. Four days later he started the club’s home opener, gaining his first major-league win in a 4-2 performance over Brooklyn. He limited the Superbas to seven hits and walked only one. According to the New York Times, the man whose nicknames compared him to the legendary Cy Young “made an excellent impression, striking out six men and keeping the Brooklyn hits well scattered.”5 On the 28th, Irv pitched the first of his seven shutouts of the year, holding the Phillies to three hits in a 2-0 Boston win. “Inability to hit Young’s delivery was responsible for the home team’s defeat today by Boston” was the rather quaint way the Bangor Daily News explained the game’s outcome.

On May 6, Irv bested Christy Mathewson in a 2-1 cliffhanger. The Giants managed but seven hits off the Boston southpaw. Irv picked up his second shutout on May 11, scattering 10 Chicago hits in a 5-0 match. South Bridgton, Maine, native Wirt Virgin “Rip” Cannell — who played all 154 games in the outfield for the Beaneaters that year — got the game’s only extra-base hit, a double.

Other highlights in Cy the Second’s steady march toward becoming Maine’s first 20-game winner of the century6 include:

May 15 — Beats Reds, 2-1, on a nine-hitter.

May 23 — Tosses a five-hit shutout over the Pirates, 1-0.

May 27 — Tosses another shutout in three-hitting the Phillies, 3-0.

June 3 — Hurls yet another shutout – again a three-hitter — against John McGraw’s Giants, 2-0. Writes the New York Times, “Young ‘Cy’ Young gave the champion New Yorks a sample of his pitching powers in the first game of a double header in this city to-day by allowing them only three hits during the entire nine innings.”7

At that point, the Boston Journal featured a large photograph of Young under the heading “Find of the Year,” noting that he had won eight of his first 11 games.8 The paper added that he had gained deserved popularity in Boston, and was “as modest as he is skilful and it is a pleasure to see him work.”9

Young’s efforts attracted attention across the land, not only in the state of Washington but in Biloxi, Mississippi, where the local paper noted his “meteoric” rise from the sandlots of Whitefield, New Hampshire, and Tenney’s being “jubilant.” In late August, it was noted that Young “has won more games than any two of the other Boston twirlers” and that in four of his games he hadn’t walked a batter.10

June 24 — Loses a heartbreaker, 2-1, to the Giants in 12 innings. Again the Times: “Young, one of the sensational pitchers of the year, who had worsted the champions on the Polo Grounds this season, and who subsequently shut them out at Boston, proved just as effective as upon the other occasions, only two hits being made off his delivery up to the ninth inning.”11

July 10 — Defeats the Phillies, 3-2.

July 13 — Five-hits the Reds in a 6-1 Boston win.

July 24 — Tosses four-hitter vs. Pittsburgh in an 8-1 win.

August 21 — Allows five hits and strikes out seven in downing St. Louis, 1-0.

September 1 — Tops Brooklyn, 4-2, on an eight-hitter.

September 7 — Again shuts out the Giants, allowing but four hits. Highlight of the game is a catch in center field by Rip Cannell in the sixth inning. The Times terms it “astonishing.”12

September 13 — Six-hits the Phillies in a 3-2 win (while also getting two hits and scoring a run).

September 20 — Defeats Brooklyn, 6-5, with a bases-loaded triple by Cannell the big blow.

What’s amazing is the number of games Irv Young could have — and probably should have — won in 1905. If he had come away victorious in all the games he lost by one run — mostly all by scores of 2-1 or 3-2 — he could well have been a 30-game winner. Wouldn’t that have put Columbia Falls on the map!

The truth is that the Beaneaters were terrible. They won but 51 games the entire season (while dropping slightly more than twice that many, 103). Young Cy’s 20 wins, therefore, constituted virtually 40 percent of the team’s victories. With any kind of run production behind him — the team’s anemic .234 batting average was the lowest in the league — Young would have easily had another eight or ten games in the win column. Ironically, Young Cy’s namesake — the winningest pitcher in baseball history and the man for whom the Cy Young Award is named — had a very similar season. Pitching for Boston’s American League entry (the team we know now as the Red Sox), he also lost one game more than he won. His record for the year was 18-19.

In late September, the Pirates offered to purchase Young for the then-hefty price of $7,500. But Boston management would have none of it. The Bangor Daily News, in a September 29 article, put the area’s many Beaneaters fans at ease. The paper reported Boston management as emphatically stating that “Such a deal will not be thought of” — Irv was just too valuable to the team.

That the offer was not accepted, however, was most unfortunate for Cy the Second. With the Pirates he would have been with a winner. With Boston he was destined to forever pitch for a loser.

In 1905, the Boston Nationals had not just one, but four 20-game losers. Joining Young in ignominy were Chick Fraser (14-21, 3.28); Kaiser Wilhelm (3-23, 4.53); and Vic Willis — later inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame — at 12-29 (3.21).

A trade sent Willis to Pittsburgh, where he won more than 20 games in each of the next four seasons, 1906-09.

There was a moment in October 1905 when Cy Young and Young Cy faced off against each other. That year, the Boston Americans and Boston Nationals faced off in a postseason best-of-seven exhibition city series, all of the games played at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. The Nationals won the first game. In the second game, played on October 10 in front of nearly 8,000 spectators, the two Youngs went head-to-head. Cy Young himself was said to have been “out to make his showing against the much-touted National League star.”13 The Americans prevailed, 3-1, with Cy Young allowing just two hits, walking no one, and striking out 15 (including the Nationals pitcher three times). Young Cy yielded eight hits (one to the Americans’ pitcher), while walking one and striking out four. Even though the Americans won Games Two through Five, the two teams played out the seven-game series, the result being that the Americans won two more games as well, taking the series six games to one.

In 1906 the Beaneaters were even more futile than the year before. Tenney was still at the helm. Their batting average dropped to .226; their won-lost record to 49-102; their starting catcher batted .189; their second baseman hit .202; and reserve outfielder Gene Good — a sometimes actor/sometimes ballplayer who weighed in at 126 pounds — stroked a lowly .151. The team made 11 errors in one game in June. They were the doormat of the league, and almost nothing Young did was going to change that.

As in 1905, Young had kicked off the 1906 season brilliantly, throwing a one-hit, 2-0 shutout in Brooklyn on Opening Day, April 12. He walked no one. The only hit was a first-inning double to left field by Harry Lumley, who then got himself thrown out trying to stretch it into three bases. Boston committed three errors, one of them by Young (who also struck out three times).

In that second season in the bigs, 1906, Irv again led the National League in innings pitched (358⅓), games started (41), and complete games (37). He was fifth in the league in strikeouts and his earned-run average remained virtually unchanged at 2.91. Yet with the club worse than ever — the Beaneaters lost 19 games in a row during one especially dismal stretch in May and June — our man from Down East saw his record drop to 16-25. Just as in 1905, Young was one of four 20-game losers on the team. In 1906, the other were: Gus Dorner (8-25, 3.65); Vive Lindaman (12-23, 2.43); and Big Jeff Pfeffer (13-22, 2.95).

The entire rest of the staff together lost only seven games. (The 1905 staff had lost nine games other than those by the four principal starters.)

John McGraw — recognizing talent when he saw it — offered $10,000 for the southpaw, only to be turned down.14 Boston management clearly liked Irv Young. So did his teammates: When he got married in September, they bought a brass bed for the new bride and groom. On September 12 in Boston, Young married Elizabeth C. Myers of Boston, “a young social favorite of the Dorchester district”; the pair had met two years earlier, when Elizabeth, a baseball enthusiast, was vacationing and saw Young pitch for the Concord team.15 The couple had one child, a daughter named Syldania, born in 1909.

Also reported as bidding to buy Young’s contract were the Chicago Cubs, in October 1906.16 And Barney Dreyfuss and the Pirates were still after him, more than doubling what they had reportedly offered a year earlier. A report in December 1906 claimed the Pirates would offer $15,000 — and 21 ballplayers! All 21 had been placed on waivers. New Beaneaters co-owner John Dovey replied, “I’m not looking for quantity, but for quality in players. I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll trade even if you’ll give me Hans Wagner, Fred Clark [sic],and Tommy Leach for Cy. Otherwise there is nothing doing.”17

Before the start of the 1907 season, the futile ballclub’s ownership changed hands. The new owners were a Pittsburgh theatrical man named John Harris and two brothers, George and John Dovey from Kentucky. The Doveys ran the team and, in their honor, the club’s nickname was changed to the Doves. It was an appropriate appellation: On the field the team was almost invariably the personification of peace. Young was, however, the last to sign. “Better late than never,” he said.18 They finished seventh, 47 games behind the front-running Cubs. Still under Tenney, their record had improved to 58-90. But the toll of constantly losing was having its effect on Cy the Second. His earned-run average jumped to 3.96; his won-lost record fell to a most disheartening 10-23.

For the third year in a row, Young had lost more than 20 games. This year he held that distinction alone; no other pitcher lost more than 16.

President George Dovey had been willing to deal Young, something he had made clear as early as July 1907, if he could strengthen the team in doing so. Though his goal was to improve the team, he apparently was fond of Young. “Mr. Dovey has only the most kindly feeling toward Young,” the Boston Globe wrote, “and it is partly on the latter’s account that he is willing to let him go, as he may be able to do better with another club than he has done this season with Boston.”19

Young started 1908, his last year in the National League, with the Doves. He was 4-9 for them and struggling a bit. “Young has not actually lowered in ability in any way,” wrote one observer, “but the National league batsmen have solved his delivery. He cannot deceive them as successfully as before.”20

On June 18, Young was traded to the Pirates for two other pitchers, Tom McCarthy and Harley Young (who, ironically, was nicknamed Cy the Third). Appearing in 16 games for Pittsburgh, Young Cy was 4-3. He pitched one truly spectacular game, a 17-inning complete-game shutout of the Dodgers on August 22 at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park, beating Sunny Jim Pastorius when he singled and came around to score for the 1-0 win. He was said to have “sat down on first base” after his long hit to center field, “reeled to second like a drunken man” on a following base hit, then — after an intentional walk loaded the bases — “lurched to home plate and fell on it” for the winning run.21

For the entire season, Young was 8-12 with his lowest-ever ERA, 2.42. It was not good enough.

In the offseason, Young worked in Boston for the National Express freight company, hauling freight and — when necessary — wielding an iron bar as leader of the company’s ice-breaking gang. It was a way to keep in shape while helping put bread on the table.22

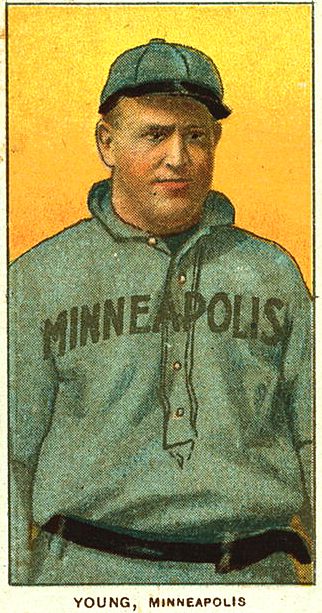

In 1909, the southpaw found himself with the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association. The Pirates dealt him to the Millers on April 13.23 Early on, he made a strong impression. Indeed, as Stew Thornley wrote, “That summer, fans witnessed the greatest single-day mound performance in the history of the Millers. Tied for first with Milwaukee, Minneapolis faced the Brewers in a doubleheader at Nicollet Park July 13. Irving (Young Cy) Young held the Brewers to four hits in the first game to win, 1-0. Young also homered in the fifth for the game’s only run. So impressive was Young that [manager Jimmy] Collins stuck with the southpaw in the nightcap; this time Young Cy held the Brewers hitless until the ninth, finishing with a one-hitter and 5-0 victory. The double shutout put the Millers two games in front of Milwaukee. The two teams scraped for the lead the next two months, but both faded in the final week, allowing Louisville to sneak into first as the season ended.”24

Young had an excellent season, winning 23 games (23-18), with a 2.31 ERA. It was enough to earn him one last shot in the bigs. Charlie Comiskey, owner of the Chicago White Sox, picked up his contract for 1910.

For the White Sox, Young pitched effectively, sporting a 2.72 ERA. Again, however, he was with a weak club. Poor Irv was forever with bad clubs: in the two years he toiled for the Chisox, the best that can be said is that their record improved from 17 games under .500 to three games over .500. The 1910 White Sox won 68, lost 85, and finished sixth. In 17 starts, Young Cy was 4-8. It is worthy of note that all four victories were shutouts.

The year 1911 was Irv Young’s last in the major leagues, and the team was 77-74. His record was 5-6, but his ERA leapt to a career-high 4.37. With a week left to go in the season, the White Sox released him back to Minneapolis.25 He won a key game against Toledo on September 24.26 The Millers finished first in the standings.

Young remained in the American Association, pitching for both Minneapolis and later the Milwaukee Brewers, through mid-1916. His teams finished first four years in succession — in 1911, 1912, 1913, and 1914. He was 16-14 for Minneapolis in 1912. His combined record for the two clubs in 1913 was 15-10. In both 1914 and 1915 he was a 20-game winner for the Brewers (20-16, 2.87) and 20-18 (2.62), respectively. He threw a league-leading seven shutouts in 1915, six of them before July 1.27 In 1916, he was 0-3 in 16 appearances.

Young later played and coached in the Southern League. Later still, while living in Orrington, Maine, he played a bit and coached there, too.

By 1918, Young was back in Columbia Falls, working in a canning factory that September at the time he registered for the military draft during the World War. Two years later, he is listed as farming — a general farm, living with Elizabeth and their daughter.

Young’s career record in the majors sees him 63-95, but with a 3.11 earned-run average that would be the envy of almost any pitcher in the past 100 years.

As a batter, he hadn’t helped his teams much. He hit for a .126 batting average at the plate with a .148 on-base percentage in 496 major-league plate appearances. He drove in 18 runs in his 209 big-league games, and scored 21 times. As a fielder, he had a .958 fielding percentage (22 errors in 527 chances.)

Young lost his wife in 1926. He himself suffered a heart attack and died unexpectedly at the home of nephew Howard Young in South Brewer, Maine, on January 14, 1935, just across the Penobscot River from Bangor.28 A rather small death notice appeared toward the back of the Bangor Daily News two days later. He was survived by his daughter, Mrs. William Hughes; a grandson, William Hughes Jr.; his sister, Minerva; and several nephews and nieces. He had been a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the Tuscan Lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons.29

One can only suspect that if Irv Young had toiled for the Giants or the Cubs or the Pirates — the powerhouse, run-scoring teams of his National League heyday — rather than the lowly Beaneaters/Doves, his passing would have instead been front-page stuff.

Young is buried in Ruggles Cemetery in Columbia Falls.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

A brief version of this biography originally appeared in Will Anderson’s self-published 1992 book Was Baseball Really Invented in Maine? and is presented here with the author’s permission. Bill Nowlin has added new material, expanding on the original biography.

Thanks to Elizabeth Stevens of the Bangor Public Library for assistance.

Notes

1 United States Census, 1900; and Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 111.

2 “Young Cy ‘Find’ Of Season,” Tacoma (Washington) Daily News; August 12, 1905: 17.

3 Young’s earlier history in New England was described in “Irving Young, Pitcher of Concord, N.H. Baseball Team, Has Enviable Record,” Boston Herald, July 4, 1904: 5.

4 “It Wants ‘Young Cy,’ ” Boston Globe, June 13, 1905: 11.

5 “National League: Brooklyns Make Good Start, but Are Finally Beaten by Boston,” New York Times, April 19, 1905: 12.

6 Bill Swift, from South Portland, Maine, won 21 games for the 1993 San Francisco Giants. This occurred after the original author’s article was written.

7 “National League: New Yorks Could Not Hit Young, but Landed on Willis and Won,” New York Times, June 4, 1905: 22.

8 “Find of the Year,” Boston Journal, June 5, 1905: 4.

9 Ibid.

10 “Sports and Athletics,” Biloxi (Mississippi) Daily Herald, August 25, 1905: 3.

11 “Winning Run Scored in Twelfth Inning,” New York Times, June 25, 1905: 9.

12 “New Yorks Shut Out, Then Beat Boston,” New York Times, September 8, 1905: 7.

13 “‘Old Cy’ Stacks Up Against ‘Young Cy,’ ” Boston Globe, October 11, 1905: 2.

14 See, for instance, “Giants After ‘Young Cy,’ ” Boston Globe, July 17, 1906: 8.

15 “‘Young Cy’ Young Weds Enthusiast,” Boston Herald, September 13, 1906: 13.

16 “Murphy Controls Chicago ‘Cubs,’ ” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, October 18, 1906: 2.

17 “After Young Cy Young,” Hartford Courant, December 18, 1906: 9.

18 “‘Young Cy’ Climbs On to Tenney Wagon,” Boston Herald, March 1, 1907: 9.

19 “Young ‘Cy’ May Go,” Boston Globe, July 22, 1907: 5.

20 Ben Tavis, “Why Able Baseball Pitchers Sometimes Lose Their Cunning,” Lexington (Kentucky) Leader, June 14, 1908: 5.

21 “Great Victory for Young Cy,” Los Angeles Times, August 23, 1908: VI1.

22 “Famous Pitcher Hustles Freight to Prepare for Next Campaign,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield), February 7, 1909: 9.

23 “White Sox Will Get Four A.A. Players,” Kalamazoo Gazette, April 14, 1909: 6.

24 Stew Thornley, On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers (Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 1988), 27.

25 “Olmstead and Young to Minneapolis,” Daily Illinois State Journal, September 24, 1911: 14.

26 “Minneapolis 6, Toledo 1,” Omaha World-Herald, September 25, 1911: 4.

27 Sam Weller, “Cy Young Leads in Using Brush,” Chicago Tribune, October 31, 1915: B4.

28 Hilda Noyes McLean, “I Remember … Baseball’s ‘Young Cy’ Young,” Down East Enterprise (Camden, Maine), November 1971: 98.

29 “Irving Young,” Bangor Daily News, January 16, 1935: 10.

Full Name

Irving Melrose Young

Born

July 21, 1877 at Columbia Falls, ME (USA)

Died

January 14, 1935 at Brewer, ME (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.