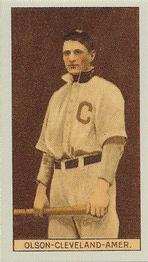

Ivy Olson

If you were drafting players in a fantasy baseball league, you would probably rely heavily on statistics to make your decisions. But if you were choosing players for a real team for an actual 154-game season, your choices might be very different. The rigors of travel, game pressures, team chemistry and other intangibles might cause you to rethink the use of statistical criteria in picking your real club. In fact, one player was quoted by F.C. Lane in his book Batting, as saying, “I believe that spirit is more important than mechanical ability. Let a player hit only .200; let him make more mechanical errors than anybody else on the team, but so long as he has the nerve and determination to win, give him to me in preference to some other fellow with twice his natural talent but without his heart.” That quoted player was Ivy Olson, and he couldn’t have described his own fourteen-year playing career more accurately.

If you were drafting players in a fantasy baseball league, you would probably rely heavily on statistics to make your decisions. But if you were choosing players for a real team for an actual 154-game season, your choices might be very different. The rigors of travel, game pressures, team chemistry and other intangibles might cause you to rethink the use of statistical criteria in picking your real club. In fact, one player was quoted by F.C. Lane in his book Batting, as saying, “I believe that spirit is more important than mechanical ability. Let a player hit only .200; let him make more mechanical errors than anybody else on the team, but so long as he has the nerve and determination to win, give him to me in preference to some other fellow with twice his natural talent but without his heart.” That quoted player was Ivy Olson, and he couldn’t have described his own fourteen-year playing career more accurately.

Ivan Massie Olson was born October 14, 1885, in Kansas City, Missouri-his parents of Swedish descent. Even early on, the Swedish Ivy was known as a truculent sort. Schoolmates with the five-year younger Charles Dillon Stengel, Olson was described by Casey as a dominant bully, the toughest kid in school. In Robert Creamer’s book, Stengel, Casey recounts a game of reverse tug of war, where two teams lined up ropeless along a wooden fence and pushed. Olson ran the game, and if he felt a boy wasn’t pushing hard enough, he’d pull him out and shove in another in his place. Olson and Stengel would reunite in Brooklyn nearly fifteen years later.

In addition to being a force on the playground, Olson was a force on the ballfield. Olson was a fine local talent; his efforts earned him a strong local reputation and a chance at a professional career, beginning in 1906 with Muskogee, Oklahoma, of the Class D South Central League. Promoted to Webb City later in 1906, Ivy’s 44-game stint with the Class C Western Association entry was hardly stellar, as he batted just .136 in 169 at bats. Another year with Webb City (.221 batting average in 133 games accompanied by 66 miscues in the field) was followed by a year with the Hutchinson, Kansas, Western Association team, and then with two years (1909 and 1910) with the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. Interestingly, in the following spring of 1911 Olson received an invitation to the Cleveland Naps spring training in Alexandria, Louisiana. How, then, does a career .225 minor leaguer with a not-so-impressive .927 fielding percentage get a big show tryout?

Stengel provided part of the answer in an article appearing in Baseball Digest, November 1952. Reminiscing of Olson, the Old Perfesser related, “They tell me he was a rough cookie on the bases in the Pacific Coast League before coming up. I hear he spiked his name and forwarding address on practically every infielder in the league. Olson loved those guys who came in rough to a base. He’d take the first crash, maybe. Next time the guy came in he’d tag him with the ball right between the horns. Very corrective method, that.” The skills learned on the schoolyards in Kansas City were perfected on the diamonds in the minors, and elevated him to the majors.

Ivy Olson made the Cleveland club in 1911, played 140 games at shortstop, and batted .261 — a huge improvement over Bill Bradley‘s .196 in 1910. Olson was so well regarded following his performance in 1911 that surprisingly, and perhaps unwittingly, manager Harry Davis named him captain of the club for 1912. Unfortunately, but understandably, Ivy’s teammates were unnerved by his constant chatter and persistent (and unsolicited) coaching. So confident was Olson of his own abilities and coaching skills, the second-year player would often lend his advice on fielding grounders to Nap Lajoie, and explain to Shoeless Joe Jackson how he could improve his hitting. A secret meeting was convened by Olson’s not so endeared teammates, demanding that Davis and owner Charles Somers make a change. The next day, centerfielder Dode Birmingham was named captain and subsequently manager in 1912.

During his tenure with the Cleveland club, from 1911 through 1914, Olson played significant time at all infield positions. While this versatility increased his value in the field, Olson’s batting average dropped to .242 in 1914. Olson’s overall baseball savvy and “ginger” were also evidenced when twice with the Naps he pulled off the nastiest of on field strategy, the hidden ball trick. Olson’s first victim was Felix Chouinard of the White Sox on September 1, 1911; the next to be poisoned was Bobby Veach of Detroit on June 23, 1914. It was this versatility and on-field cleverness that attracted Olson to the Cincinnati Reds management in the off-season. On December 14, 1914, Ivy’s contract was picked up by the Reds.

In entertaining off-season hyperbole, the newspapers announced the acquisition by stating that Olson was “one of the best infielders and general utility men in the business. He is not a very hard hitter, but a dangerous one. As a baserunner he is neither fast nor slow, but is a good man on the sacks. He is a very smart ballplayer and is always out to win. Manager [Buck] Herzog made a strong play in securing him.” Could there be a more muddied definition of mediocrity?

So much for the hyperbole, for on July 17, 1915, after playing only 63 games and batting .232 with the Reds, the Brooklyn Robins claimed him off waivers. Ivy played only 18 games with the Ebbets Field natives, hitting a miniscule .077. But his love/hate affair with the Brooklynites had just begun.

What made Brooklyn manager Uncle Robbie, Wilbert Robinson, go get Ivy Olson? It couldn’t have been his Dave Stapleton-like batting average trend. (Stapleton holds the dubious distinction of playing seven years in the majors, with each year’s batting average lower than the previous year’s, while Olson’s had only declined consecutively for five years through 1915.) Nor was Olson’s glovework the reason for his relocation to Brooklyn. More likely it was that pugnacious Ivy Olson style. Here are some sample news items describing Ivy at work:

May 28, 1914 — Boston’s Harry Hooper leads a successful triple steal against Cleveland that results in Ivy Olson, Dode Birmingham, and Fred Carisch getting tossed for protesting too vigorously.

July 7, 1915, New York Times — “Free-for-all Fight by Cubs and Reds – Olson and Good Clash and Others Take a Hand – Umpire Carries Off Troublemaker. ” In this foray, after Wilbur Good of the Cubs had tripled and spiked Olson, “Olson became enraged and struck at Good. In a moment they were exchanging blows. The local players came to the assistance of Good. Cincinnati players joined the fracas, and Umpire [Ernie] Quigley rushed across the field and picked Olson up and carried him to the stand. Olson attempted to free himself, but Quigley held him until his team mates could quiet him down.”

April 21, 1916, New York Times — “Fists Fly in Boston Game with Dodgers – Olson and Maranville Clash Over Some Rough Work, but Umpire Stops Them. ” [Rabbit] Maranville tried to knock the ball out of Olson’s glove in a play at third, but “Olson resented this, and promptly began to bang Maranville on the shins with the ball. This was the signal for the real fun, Maranville’s punch for the head missing its mark but striking Ivan on the knee. Then Ivan’s return sweep whizzed past the Rabbit’s head. Umpire [Cy] Rigler, who had followed the play to third, the jumped after Olson, grabbing him about the neck and pulling him away, while half a dozen ball players made a circle around Maranville. Both men wanted to continue, but Rigler evidently figured out that the gate was too small and that the 800 fans had had enough for their money.”

May 19, 1920, New York Times — “Row is Averted as Cubs Beat Robins – Olson Starts Trouble in Ninth, but Umpire Byron Steps in to Quell Outbreak. ” This incident began after an Olson errant throw placed Les Mann at first. A steal of second was thwarted by a slam of the baseball upon the neck of Mann by Olson. “Ivan Olson, Brooklyn’s shortstop, rankling, evidently, under the unpleasant complexion of the pastime and tiring of making unlawful heaves in the direction of first base, sought a little variety in a game of fisticuffs at Ebbets Field yesterday, when the Robins and Chicago Cubs renewed hostilities. Only the presence of mind of Umpire Lord Byron, officiating on the bases, and several cool heads among the players prevented what might have resulted in an exchange of blows afield.”

Olson’s fiery disposition and some intuitive acquisitions by Robinson helped bring the national league pennant to the Flatbush Faithful in 1916. The checker-uniformed Robins lost to the not yet Ruthless Boston Red Sox in six games. One play by Ivy Olson in the third inning of the final game inured him to baseball lore when he placed himself in the record book for making two errors on one fielding chance. He first fumbled a grounder by Hal Janvrin, allowing him to reach first base. With the bobble completed, Olson then threw the ball to second when there was no one there to take the toss, allowing further advance of the runners. Though others have made three errors in one World Series game, only Olson and Willie Davis in 1966 have “earned” the distinction of making two errors on the same play.

Olson’s glovework often made headlines, not just in the World Series. Samples of his erratic work in the field include:

July 8, 1921, New York Times — “Pirates Trample Dodgers in Dust – Error by Olson and Schupp’s Wildness Contribute to Brooklyn’s Downfall, 5 to 3. ” Later, “Mr. Olson produced a very unhandy error that allowed the Pirates to gallop into the lead in the sixth inning.”

June 30, 1922, New York Times — “Errors Aid Braves in Beating Robins – Olson’s Two Fumbles Enable Boston to Win by 3-2. ” “That Leon Cadore did not prove the victorious twirler was due to an unusually poor streak of fielding in the sixth inning by Ivan Olson. Ivan was so much of a weak link in the infield defense of the Robins that he faltered twice in succession, thus paving the way for a trio of runs, all that the Braves made the entire game.”

Another newspaper account of an errant throw to first by Mr. Olson notes that the ball actually hit Robinson in the paunch as he dozed in the dugout and woke him up!

Ivy actually did have a talent for making clutch hits, but just as often it seemed he had the same knack for making clutch errors. And sometimes both would happen on the same day. A New York paper described his adventures from September 16, 1922 this way: “From a spectacular standpoint Ivan Olson was the star of the double-header played at Ebbets Field yesterday afternoon between the Brooklyn Robins and the Chicago Cubs. His single in the tenth inning of the second game brought victory to the Robins by 1 to 0 and his fumble in the ninth inning of the first battle paved the way for a single which sent two runs over the plate for a 7 to 5 victory for the Cubs. All through the second contest Ivan stood the razzing of 10,000 fans for his misplay in the opening struggle, but with his hit that won the game the razzing turned to cheers.”

Brooklyn fans loved their erratic Swedish Ivy, through both his clutch hits and untimely errors. Wrote John Lardner, “…in the sphere of inverted love, no hometown butt was ever denounced more passionately and fondly than a Brooklyn shortstop named Ivy Olson. In Ivy the fans saw themselves and the humble fortunes of the team as a whole. Booing him was part of Brooklyn’s way of life.”

How did Ivan deal with the cheers and jeers of the Flatbush Fans? Ivy devised his own simple unique solution — he stuffed his ears with cotton! Once in a while, when he’d make a terrific play and the fans would cheer, he’d take the cotton out of his ears long enough to hear the hazzahs, then stuff the cotton back in again with a grin — which only endeared him to the crowd even more.

As much as the fans loved Olson, Olson loved the game. His passion for baseball is exemplified by his role in the still longest major league game ever played. That marathon 26-inning game of May 1, 1920, between the Robins and the Braves might never have happened but for Olson’s RBI single in the top of the seventh and great play in the bottom of the ninth to prevent the winning run from reaching home. But when umpire Barry McCormick halted festivities because of approaching darkness, Olson pleaded, “Come on, Barry — let’s play one more inning. I want to tell my grandchildren that I once played the equivalent of three games in one afternoon.” Ernie Banks would have loved Ivy Olson.

Ivy hung up his infielder’s glove in 1924 at the age of 38. He went on to manage at Sarasota and Pocatello before returning to Brooklyn as a coach through 1931. He later coached third base for the New York Giants in 1932 before being released in July of that year. Ivy had married Miss Mabel Ivie in July 1920, and had one daughter. The Olsons moved to the West Coast after his full retirement from baseball.

Along with 14 other members of the 1916 pennant-winning Robins, Olson was invited back to Brooklyn to help inspire the 1949 Dodgers against the Yankees, who were managed by Olson’s former school and teammate, Casey Stengel. The still swaggering Olson loved the attention and cheers of the Ebbets Field fans. The inspirational effort fell short, of course in 1949, and the Dodgers had to wait six years later to defeat the Stengel-led Yanks.

Olson’s career statistics were good but not great: .258 batting average, 191 doubles, 69 triples, 13 home runs, and 1,575 hits in 1,574 games. His RBI total was 446, and he scored 730 runs, and walked 285 times. Olson was known as a contact hitter, and struck out only 301 times in 6,111 at bats. With his .938 fielding percentage, he is still considered one of the National League’s best defensive players of his era. The highlight of Ivy’s career might have come in a losing cause in the 1920 World Series against Cleveland, where he batted .320 while playing all seven games.

Perhaps Ivy does hold one record that will never be broken. It is said that Olson carried a rulebook in the back pocket of his uniform in each of his 1,574 games. During an umpire’s oration, he would take out the book and riffle the pages with a flourish. But he would often get the thumb before he could reach the appropriate reference to the rule in question.

When Ivy Olson passed away on September 1, 1965, he was remembered most by the Brooklyn fans. On September 10, 1965, Murray Robinson of the New York Journal-American wrote, “…there was a special niche for Ivan Olson, the club’s swaggering bow-legged shortstop; a spike-scarred, swarthy veteran with a barrel chest, high shoulders, a sharp nose and chin, and piercing black eyes. All Ivy Olson needed to make him look like a pirate of old was bandana on his head, a patch over one eye, and a cutlass instead of a bat. Maybe that’s why we kids in the left-field bleachers were so enamored of him.”

Aggressive, brash, colorful, devilish and certainly entertaining, there’s definitely a place for an Ivy Olson on everyone’s team. Forget the statistics, you need a sparkplug like Ivy — how else would you survive a long, exhausting 154-game schedule in the dead ball era?

Sources

Ivy Olson’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Creamer, Robert. Stengel. Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Lane, Frank. Batting. Baseball Magazine Co., 1925.

Kavanaugh, Jack and Norman Macht. Uncle Robbie. SABR, 1999.

Stengel, Casey. Baseball Digest. March, 1952.

New York Journal-American. September 10, 1965.

New York Herald. Many articles during Olson’s career.

New York Times. July 7, 1915; April 21, 1916; May 19, 1920; July 8, 1921; June 30, 1922.

Full Name

Ivan Massie Olson

Born

October 14, 1885 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

Died

September 1, 1965 at Inglewood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.