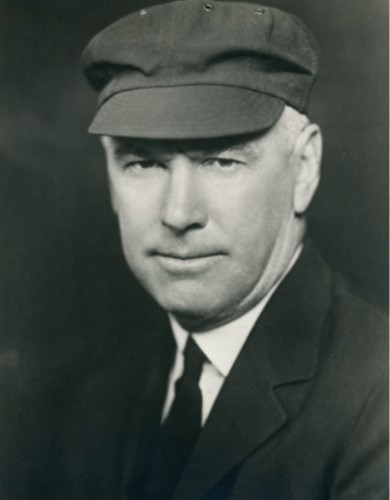

Ernie Quigley

Before the age of television, umpires worked in anonymity, only a handful of dominant personalities gaining widespread recognition. Among the virtually unknown arbiters is Ernest Cosmos Quigley, an outstanding and influential umpire who also was the greatest sports official in history. Indicative of how overlooked he has been is the fact that even a fairly comprehensive listing of Canadian-born major-league players, coaches, managers, and umpires, the latter including arbiters Jim McKean and Paul Runge, omits Quigley.1

Before the age of television, umpires worked in anonymity, only a handful of dominant personalities gaining widespread recognition. Among the virtually unknown arbiters is Ernest Cosmos Quigley, an outstanding and influential umpire who also was the greatest sports official in history. Indicative of how overlooked he has been is the fact that even a fairly comprehensive listing of Canadian-born major-league players, coaches, managers, and umpires, the latter including arbiters Jim McKean and Paul Runge, omits Quigley.1

For 31years, 1913-1944, “Quig” served the National League with distinction as a field umpire, supervisor of officials, and public relations director. And for 26 of those years, he not only umpired major-league baseball, but also gained national prominence officiating major-college football and basketball, in all some 250 games a year. (It was then possible to combine major-league umpiring with officiating other sports because college schedules were more seasonal and limited in number—typically eight football and 18 basketball games in the 1920s.) In over 40 years of officiating, Quigley estimated working some 5,400 baseball, 1,500 basketball, and 400 football games logging 100,000 miles a year in coast-to-coast travel.2 When baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis wondered how his wife liked her husband being gone 325 nights a year, Quigley quipped: “Mrs. Quigley likes it fine. We’re constantly getting reacquainted.”3

Ernie was born on March 22, 1880, in Newcastle, New Brunswick, Canada, to Lawrence B. Quigley, an Irish immigrant, and Mary J. (Weir) Quigley, of Saint John, New Brunswick. His father, a salesman, sought greater opportunities by moving the family to Concordia, Kansas, in the 1880s. Quigley was an all-around athlete at the University of Kansas, but baseball was his favorite sport. He turned professional in 1905 as a shortstop with Topeka in the newly formed Class-C Western Association. His professional career, which included occasional stints as a manager, took an abrupt turn in 1910 when, sidelined by a broken hand, he agreed to replace an umpire who had quit the Class-C Wisconsin-Illinois League. Quigley was a natural: Three years later he reached the major leagues.

A National League umpire for 26 years, he umpired 3,351 games, the seventh most in major-league history at the time. His career highlight was umpiring 38 games in six World Series including the infamous 1919 “Black Sox” series between Chicago and Cincinnati in which he worked home plate in Games Three and Seven. Shocked to learn that eight White Sox players had thrown the Series, Quigley said he “never saw a team try harder to win, and that they were beaten on the square by the superior strength of the Reds.”4 He was also behind the plate on June 1, 1923, when the New York Giants beat Philadelphia 22-8, setting a modern league record by scoring in all nine innings. He achieved another distinction when he and Charley Rigler in 1920 became the first National League umpires ever to “hold out” for more money before eventually signing their contracts.

Quigley experienced the physical dangers of umpiring home plate. On July 11, 1923, he was hospitalized for several days after being knocked unconscious by a foul ball to the left temple in the first game of a doubleheader. Cy Pfirman had to work the second game alone, making Quigley indirectly responsible for the last major-league game officiated by a single umpire.5 In 1934 another foul ball hit him on the jaw; temporarily unable to speak, he had to communicate for days with pencil and paper. And in August 1934 he was overcome with heat exhaustion after the first game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia.

Sometimes Quigley just had a bad day. One such occurred while umpiring behind home plate in the 1935 World Series. In the fourth inning, while racing toward the Detroit dugout to track a foul popup, he “slipped in a puddle and was like to bust his neck falling into the Tigers dugout.”6 Another unfortunate occurrence came after a game at Wrigley Field in 1933, when Quigley suddenly collapsed unconscious in the umpire’s dressing room. Taken to a hospital, he had not suffered a stroke as feared, but instead had been severely shocked after backing into an exposed electrical wire while exiting the shower. Contrary to doctor’s orders, he returned to the diamond the next day.

As with all umpires, Quigley’s decisions occasionally prompted arguments from players and managers as well as boos and even barrages of pop bottles from fans. On balance, however, he reportedly had good relations with players and managers owing to his diplomatic posture, decisiveness in upholding decisions, and total command of the rulebook. Casey Stengel thought him “a splendid man who knew all the rules.”7

He repeatedly demonstrated knowledge of the most intricate applications of both playing and scoring rules and adamantly refused to tolerate verbal abuse. Instead of debating decisions, Quigley turned challengers away by sternly asking: “Now just what was it you said?” Continuing the discussion resulted in ejection from the game. He lost control once, early in his career on July 22, 1915, when he punched Johnny Evers, claiming that the Boston second baseman had stepped on his foot during an argument. Umpire and player were each fined $100.

Quigley enjoyed universal respect for his demeanor as well as his umpiring ability. At a time when players and managers like John McGraw were openly combative and profoundly profane, some umpires retaliated in kind with vulgarities and insults. Not Quigley, who had taught history, English, mathematics, and physical education at St. Mary’s College in Kansas. Fred Lieb, the most prominent baseball writer of his day, who covered baseball for three New York City newspapers from 1909 to 1934, recalled that Quigley was “strictly high class” and “spoke with the diction and proficiency of a college professor.” When McGraw once shouted, “Don’t put on any airs with me,” Quig replied: “One doesn’t put on airs by speaking good English.” To a player’s uncomplimentary comment, he once responded: “Sarcasm, sir, is the weapon of the weak-minded.” He enjoyed the respect of adversaries. He regarded Boston’s Tony Boeckel, with whom he had numerous run-ins, as “the most pestiferous player in uniform,” but when a serious illness sent Quigley to the hospital, Boeckel sent flowers.8

Quigley’s contributions to umpiring extended abroad. After the 1928 season, the second most senior National League umpire to Bill Klem spent three months on an instructional mission to Japan with three recently retired ballplayers, including Ty Cobb. Treated “like royalty,” he traveled throughout the country umpiring ballgames, lecturing, and conducting clinics, and even establishing schools for baseball umpires and basketball referees.

When Quigley retired at the end of the 1936 season, National League President Ford Frick appointed him the league’s first supervisor of umpires. (The administrative appointment theoretically ended Quigley’s on-field duties, but he returned to the diamond as a replacement umpire for several games in April and May 1937 and again in July and September 1938.) His duties as umpire-in-chief were to supervise the current umpire staff, review complaints of their decisions and performances, adjudicate fines levied for confrontations with umpires, and interpret rules for Frick and the teams. In this capacity Quigley’s legendary knowledge of the rules was put to good use. Asked by Frick to facilitate the creation of a uniform code for both the major and minor leagues, he called senior circuit umpires to a three-day meeting to review “every word of every rule,” posing questions about the formal rules as well as unusual situations and vague applications. The undisputed authority on baseball rules, he routinely received inquiries about interpretations from across the country and from as far away as Australia and Japan.

In December 1940 Ford Frick designated Quigley the league’s first full-time director of public relations, a position he held until July 1944. The reassignment was both political and practical. The National League’s Bill Klem, the most famous and respected major-league umpire, had retired in November 1940. When Tommy Connolly, Klem’s famous counterpart in the American League, retired in 1931, he became major-league baseball’s first umpire supervisor, so the National League followed suit by appointing Klem, “the King of Umpires,” to the like position. Because Quigley had served concurrently as the voice of the league and umpire supervisor, the expansion of his public relations functions was apt. And in recognition of his skill in identifying new talent, he continued to be in charge of scouting for new umpires.

Ever the ambassador for sports, Quigley taught from 1938 to 1940 a summer-school course at Columbia University. To facilitate instruction on baseball rules in his course on Techniques and Mechanics of Umpiring, he invented Magnetic Baseball, a magnetized “blackboard” featuring the outline of a baseball diamond. By using a series of colored magnetized rings to represent players and umpires, he was able quickly and clearly to diagram positioning on various plays.9 In the early 1940s, Quigley joined with fellow National League umpire Charlie Moran, a former football player and coach, to publish “educational” pamphlets on “All phases of Foot Ball, Basket Ball and Base Ball.”

No less significant was his public persona: The highly visible, personable, and outgoing Ernie Quigley did much to put a “human face” on umpires, thereby countering the conventional negative attitudes toward baseball’s men in blue serge suits. It was commonplace for baseball players to endorse a variety of commercial products, but Quigley was the first sports official known to do so, pictured and identified as the umpire supervisor in a newspaper advertisement: “We solved the timing problems of baseball when we adopted Longines Watches for the use of all umpires.”10

Sensitive to verbal abuse from fans and press coverage that called attention to controversies, umpires typically were reticent and inconspicuous off the field. Quigley, however, relished the spotlight. He eagerly made a well-publicized appearance on a WEAF radio sports interview program in New York explaining how umpires dealt with difficult and unexpected situations, and regularly joined civic leaders at a variety of celebratory community affairs ranging from the annual Brooklyn Dodgers Knot-Hole Club fete to a joint Sportsmanship Brotherhood-New York City Baseball Federation dinner honoring Connie Mack, the 78-year-old owner-manager of the Philadelphia Athletics.11 And he occasionally returned to the field as a celebrity umpire, as for the annual Army-Navy Day game at West Point and benefit games between teams from two New York military bases.12 Perhaps his most effective outreach activity was the thrice-weekly evening radio program he hosted on station WIBW in Topeka for 17 years, from the late 1920s to the mid-1940s, talking about sports in general but mostly baseball, answering questions from listeners.

Although overshadowed in the minds of fans and historians by some of his more flamboyant contemporary National League umpires, Quigley’s on-field reputation and administrative contributions following retirement testify to a long, distinguished, and influential career as a major-league umpire. In 1960, looking back over a half-century of covering baseball, Fred Lieb in his weekly column for The Sporting News, declared: “It is doubtful if any man ever had the rules of baseball, football and basketball at his finger tips as did Quigley. Unless it was Bill Klem, no National League umpire of his day commanded as much respect as did Quigley.”13

The baseball diamond provided Quigley with his greatest officiating success, but football and basketball brought even more widespread recognition. For 40 years, 1904 to 1943, Quigley worked college football games, for most of his career serving as the referee, the head crew official. (He missed two seasons: 1928 because of the baseball trip to Japan and 1938 due to a severe ankle injury in September that kept him on crutches until the start of the 1939 baseball season.) He thought refereeing football was easier than umpiring baseball in one fundamental respect: Football players “usually vent their enthusiasm on their adversaries instead of taking it out on the officials.”14 Quigley was in demand for “big games” across the country including three Rose Bowls, and as with baseball, his command of football’s rulebook was unrivaled; after retiring from the gridiron, he served as the ranking member of the NCAA Football Rules Committee from 1946 to 1954.

Quigley refereed college basketball from 1906 to 1942, rising to the top of basketball officialdom in the United States. In addition to a full slate of regional college games each year, he was selected to work premier national contests and officiated more national tournaments than any other referee. He was the second referee to be enshrined in the National Basketball Hall of Fame. Departing from the customary staid demeanor of sports officials, Quigley became the first flamboyant, “colorful” official, famous for exaggerated verbal and physical gestures as well an unorthodox behavior. To Quigley, the whistle was merely a device to announce a referee’s presence. His trademark call became world renown. Upon detecting a violation, Quigley pointed an accusing finger at the offending player and in a stentorian voice shouted: “YOU can’t D-O-O-O that!” – a call invariably echoed by the spectators. His trademark call was so well known that in 1945 he received in Lawrence, Kansas, a letter from Europe addressed only as “You Can’t Do That! U.S.A.”15

His officiating career finally over, Quigley returned in 1944 to his alma mater, the University of Kansas, as the athletic director. He promptly retired the department’s debt and launched a major resurgence in its athletics program by reinstituting five sports canceled during World War II and hiring superb coaches who elevated football, basketball, and track to championship levels. After he retired in 1950, the school’s first baseball field, built in 1958, was named Quigley Field in his honor, the first and only ballpark named after an umpire.

Ernest C. Quigley underwent extensive cancer surgery in September 1958, and finally succumbed to the disease on December 10, 1960, age 81. He is interred in Mount Calvary Cemetery in Lawrence. Perhaps the best epitaph for the unique one-of-a-kind official came from his alma mater’s student newspaper: “The most famous man in the field of sports.”16

Notes

1 William Humber, Cheering for the Home Team: The Story of Baseball in Canada (Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1983), 149.

2 This essay is extracted with revisions from my comprehensive account of Quigley’s career. See Larry R. Gerlach, “Ernie Quigley: An Official for All Seasons,” Kansas History vol. 33, no. 4 (Winter 2010-2011): 218-239.

3 Ibid.

4 The Sporting News, October 7, 1920.

5 John Schwartz, “From One Ump to Two,” SABR Baseball Research Journal 2001: 85-86.

6 Chicago Daily News and New York World Telegram, October 7, 1935.

7 Joseph Vecchione, ed., The New York Times Book of Sports Legends (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 332.

8 The Sporting News, July 29, 1915; New York Times, January 9, 1927, December 5, 1929, and December 11, 1960.

9 “Magnetic Baseball á la Quigley,” August 1941 press release, Ernie Quigley File, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York. See also New York Times, July 30, August 3, and August 11, 1941; Topeka Capital, August 3, 1941.

10 New York Times, July 4, 1937; unidentified newspaper advertisement, September 29, 1940,

Quigley File, National Baseball Library.

11 New York Times, July 31 and August 1, 1937; April 13 and 15, 1940; October 4, 1941.

12 New York Times, June 1 and 13, 1941.

13 The Sporting News, December 21, 1960.

14 Sporting Life, December 12, 1914.

15 University of Kansas Sports Bureau News Release, August 2, 1945. Ernest C. Quigley Collection, Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

16 University Daily Kansan, December 12, 1960.

Full Name

Ernest Cosmos Quigley

Born

March 22, 1880 at Newcastle, NB (CA)

Died

December 10, 1960 at Lawrence, KS (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.