Jack Coffey

“Atta-boy, Frank”1, the slick-fielding Fordham University shortstop shouted to the diminutive second baseman with every successful double play turned on the practice field at Rose Hill. The oft-repeated ritual helped propel the shortstop to a major league contract before college graduation. More than 50 years later, when the shortstop-turned-baseball-coach-turned-Fordham institution had to retire, the keystone partner gave the keynote address. Of course, by then, the shortstop, Jack Coffey, referred to the second baseman in more deferential tones, because the second baseman had become the Archbishop of New York, Francis Cardinal Spellman, There are not many professional baseball players who have to list their stint in the major leagues among the least of their accomplishments, but such is the case for Jack Coffey. His greatest accomplishment was the positive impact he had on the lives of the numberless throng of undergraduates. Yes, Coffey was a coach at Fordham, but he was also a teacher, friend, advisor, cheerleader, and confidant to many, many young men in his 54-year association with Fordham. While his milieu was athletics, his influence was much wider. As sportswriter Caswell Adams wrote, “There hasn’t been a Fordham man, bookworm, crapshooter, or athlete who hasn’t felt the influence of Jack.”2

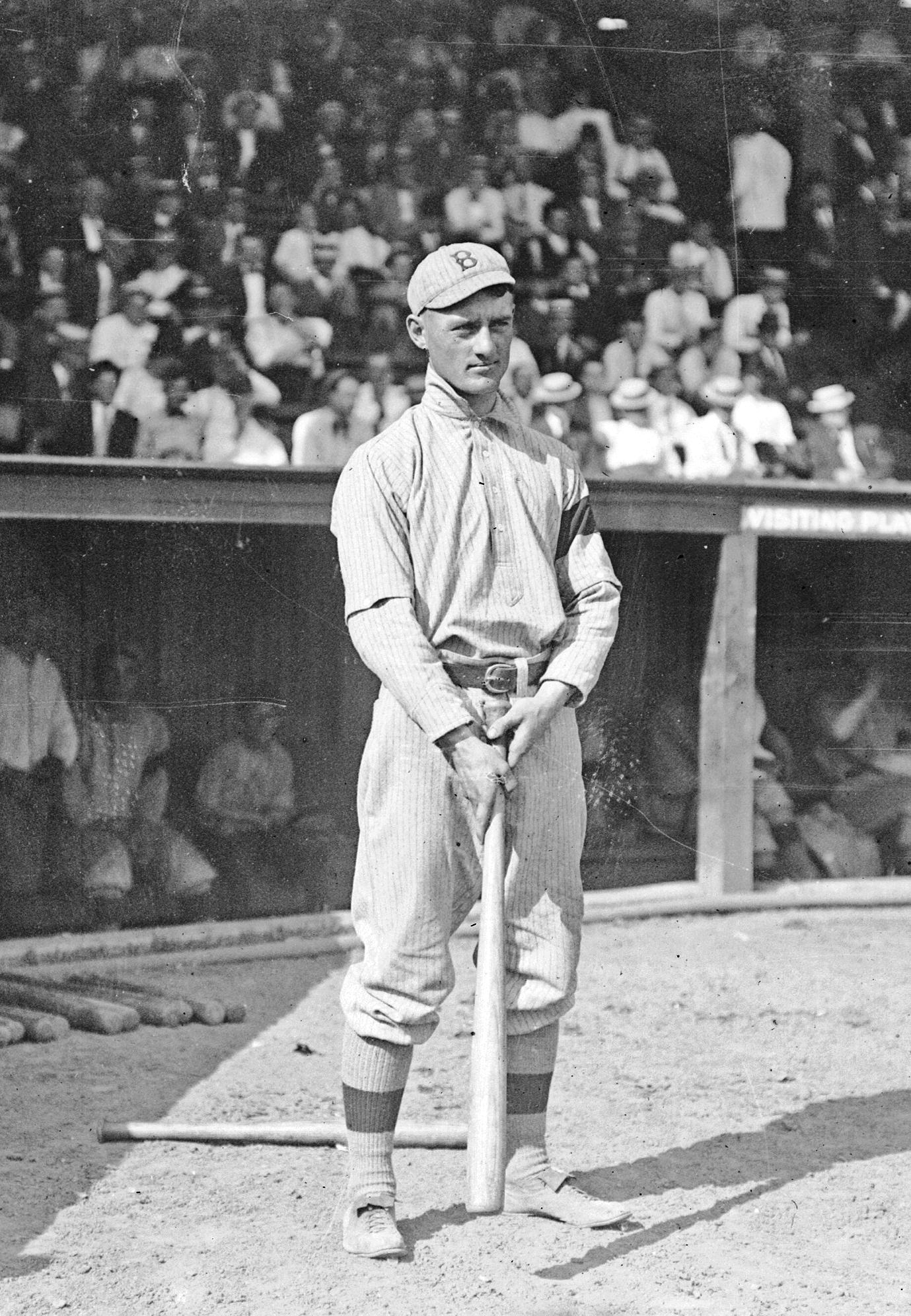

John Francis “Jack” Coffey, the son of immigrants, was born January 28, 1887, in New York City. Jack’s mother was born in England; his father, Michael, in Ireland. Jack attended Morris High in the Morris Heights section of the Bronx, playing baseball and football there. In the fall of 1905, Jack entered St. John’s College at Rose Hill in the Bronx (in 1907, St. John’s College became Fordham University), and excelled at academics and sports. He won eight varsity letters at Fordham, four each in baseball and football.3 His first game for the Maroon was a football game against Rutgers in the fall of 1905. Left tackle Coffey would drop off the line into the backfield to take the pitchout; the play, which became known as the “Coffey-Over,” worked for three touchdowns in that initial contest. While Coffey was quite adept at football, baseball was destined to become his career. The speedy Coffey was the star shortstop for four years and was the Rams’ team captain in 1909. During his playing career at Fordham, he was a teammate of three future major league players: pitcher Dick Rudolph, who won two World Series games with the 1914 “Miracle Braves,” and infielders Dick Egan and Dave Shean.

After the 1909 Fordham baseball season ended, Coffey signed a major league contract with the Boston National League franchise (the team was known then as the Doves, after team owner George Dovey but Coffey later joked the name derived from “their pacifistic tendencies.”)4 The 5’11”, 178 pound Coffey joined the Doves on June 23 at the Polo Grounds in New York City, where the Boston nine were scheduled to play a doubleheader against the Giants. The Doves were a very bad team, 13-35 as the day started, on their way to a 45-108, last-place finish. Luckily for Coffey, the Doves were desperate for help. Coffey entered the first game in the bottom of the eighth after starting shortstop Bill Dahlen was ejected for arguing a close play at third base. In the top of the ninth, with the score tied, 4-4, Coffey had his first major league at-bat. It came against future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson, who had entered the game in the ninth in relief of starter Rube Marquard. The right-handed-hitting Coffey, who later recalled fouling off about a dozen pitches, struck out. In the bottom of the ninth, with the score still tied, Coffey made an error that gave the Giants an opening to win the game, 5-4. Between games, Coffey was honored with a ceremony on the field by “his young Westchester County friends.”5 He was given a gold watch and a floral horseshoe. Coffey started the second game at short. He got his first major league hit, a single, off the Giants’ Doc Crandall. Coffey also scored a run and made another error as the Doves were drubbed, 11-1.

Coffey became the everyday shortstop for the 1909 Doves, playing in 73 of 80 games between June 23 and September 9. He had a difficult time in the field, making at least one error in five of his first six games. He would go on to make 40 errors in 73 games for an .896 fielding percentage, well under the league average. He acquitted himself better at the plate for a while, reaching .268 (on a team that hit .223 for the season) before settling at .187. He had a 3-for-5 day on July 8 against St. Louis while playing errorless ball in the field. The Boston Globe enthused: “Coffey made it plain to all that he is a high class ball player”.6 Arthur D. Cooper wrote, “The Fordham shortstop has partially braced up an infield which as yet is a little wobbly. Coffey has certainly made good.”7 Coffey was moved up in the batting order from seventh to fifth and even batted in the third spot on occasion.

On July 16, Coffey was reunited with fellow Fordham alum Dave Shean, whom the Doves had acquired from the Phillies. By July 27, the Boston Globe noted, Coffey seemed to play better when the “Arlington boy [Shean]”8 was playing second. On July 26, the Doves were playing the Giants at the South End Grounds; Boston started Al Mattern. The Giants went with Leon Ames. Coffey, batting third, hit a long line drive to right center field with one on in the first inning. Giants center fielder Bill O’Hara cut in front of right fielder Moose McCormick, attempting to make the catch. The ball went off O’Hara’s glove deep into the right-field corner, allowing Coffey to circle the bases. The Globe gave Coffey credit for a home run. No error was given to O’Hara or McCormick. Although the Boston Herald and Journal described Coffey’s hit as a “long liner to right center and under almost any circumstances would have been an out,”9 the box score shows a home run for Coffey. The Boston Post gave Coffey credit for a triple but no error to O’Hara or McCormick. There is no further explanation of how Coffey scored. The New York Times credited Coffey with a home run in the box score and noted only that “O’Hara made an error of judgment” in the account of the game. The game was suspended because of darkness after 17 innings with the score tied, 3-3. Coffey reminisced about this home run to Arthur Daley10 and was proud of hitting a home run in each major league. He has not, however, been given official credit for the four-bagger.

After a forgettable August, Coffey went back to Fordham in early September to finish his bachelor’s degree and to coach the freshman football team. In late December, the Indianapolis Indians of the Class A American Association announced they had obtained Coffey from the Boston Nationals. His amateur eligibility exhausted, Coffey could not play for his college baseball team so, in 1910, he coached the Fordham nine to an 18-2 record.

With his degree in hand and the college season over, Coffey played for the 1910 Indians. Managed by former major leaguer Charlie Carr, the Indianapolis team finished fourth (83-85) in the eight-team league. Coffey, playing shortstop, hit .226 with six triples, four doubles, and 16 stolen bases in 93 games. In 1911, Coffey’s contract was purchased by the Denver Grizzlies of the Western League (Class A). The 1911 Grizzlies, managed by Jack Hendricks, were arguably the best team Denver ever fielded in the Western League and one of the finest minor league teams ever. Pitcher Buck O’Brien was 26-7 with the Grizzlies and, after a September call-up, was 5-1 with a 0.38 ERA for the Boston Red Sox. The Grizzlies reached first place in June and never let up, winning 111 and losing only 54, leaving the second place St. Joseph (Missouri) Drummers 18 games behind. Coffey had an excellent year for the Grizzlies, playing in 168 of the 169 scheduled games and hitting .278 with five homers, nine triples, 31 doubles, and a Western League record 68 stolen bases. He fielded .923, fourth in the l/League among everyday shortstops. An article in Baseball Magazine about the 1911 Grizzlies said, “The shortstop position had for several seasons been the weakest place on the Denver infield. Jack Coffey was bought from Indianapolis and took care of the position so well that the other shortstops in the league were forgotten”.11

The Grizzlies also finished in first in 1912 and 1913 although in not so dominating a fashion as the 1911 squad. Coffey raised his batting average to .293 in 1912. He hit a career-high nine home runs along with 11 triples and 23 doubles over 147 games and stole 43 bases. For the 1913 Bears, as they were now known, Coffey’s power numbers were down from the previous year but he still hit .291 with 39 stolen bases while playing 154 games at shortstop.

In addition to his work with the Bears, Coffey was a co-manager of the Fordham varsity baseball team in 1912 and 1913. He was instrumental in the Rams’ early season workouts and with the team selection before leaving to join the Western League in April.

After the 1913 season and three successive Western League crowns, Denver team owner and president James C. McGill asked skipper Jack Hendricks to manage another of his baseball properties, the Indianapolis Indians. McGill then named Jack Coffey to succeed Hendricks. This was Coffey’s first foray into the ranks of player-management, a role that would last until the end of his minor league career. The pressure of management, apparently, had a salutary effect on Coffey’s playing. In 1914, he had the finest season of his professional career. Coffey achieved career highs in at-bats (628), batting average (.330), total bases (287), hits (207), triples (15), and runs (116) while playing in 165 games. The Bears finished second, however, winning 96 and losing 72.

In August of 1914, Coffey signed a contract extension, at an increased salary, to manage the Bears in 1915. In September 1914, though, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased Coffey’s contract for $1,500. On September 21, the New York Times declared: “Coffey to Succeed Hans Wagner“.12 The story that followed, however, dampened the grandiose claim somewhat. Coffey had not yet signed a contract with the Pirates. Pittsburgh scout Chick Fraser was dispatched to Denver to induce Coffey to sign. Coffey was balking at the idea, though. If he was going to move east, he wanted to be well compensated. Coffey was using the newly former Federal League as a bargaining ploy. Federal League teams in Indianapolis and Chicago were interested in Coffey. In the end, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss would not pay Coffey what he wanted and Coffey was back with Denver as a player-manager in 1915. Coffey’s numbers tailed off that season, as they were bound to after his stellar 1914. He played in only 105 games but stole 34 bases and hit a respectable .282. He also saw some time at third base for the first time in his professional career. As a manager, he guided the Bears to another second-place finish at 82-55, three games behind Des Moines. After the season, St. Joseph owner Jack Holland tried to pry Coffey loose from Denver. Coffey told Holland he was under contract with the Denver club for 1916. McGill, miffed because of the attempted backdoor deal, set the price for Coffey’s contract very high. Holland declined to pay it and the popular Coffey appeared set to play and manage another year in Denver.13 It was not to be, however. Before the start of the 1916 season, Coffey’s contract was sold to the San Francisco Seals of the Class AA Pacific Coast League.

Jack Coffey was joining another very good team. The Seals won the PCL crown in 1915, posting 118 victories against 89 defeats under manager Harry “Fighting Harry” Wolverton, a nine-year major league veteran and one-time New York Yankees manager. Wolverton remained the manager for 1916 and Coffey was relegated to player-only status. The Seals played 206 games in 1916 (the PCL typically played the most games of any professional circuit). After briefly attaining first place in the league, the Seals fell to third before finishing in fourth place at 104-102. Their new shortstop had an offyear as well. Coffey hit only .223 in the tougher league, managing just two triples and 13 doubles in 135 games. Coffey had another good year in the field though. The shortstop fielded at a .948 clip in 135 games.

Coffey, now 30, was back in the Western League in 1917, this time as player-manager for the Des Moines Boosters. Coffey guided the Boosters, including future major league star Lefty O’Doul, to a 55-35 first-place finish for the first half of the season and a 29-27 fourth-place finish in the second half. The Boosters beat the Hutchinson (Kansas) Wheatshockers four games to two in the league playoff, winning the Western League crown. Coffey, playing second base, had a better year at the plate. He hit .289 over 142 games with four homers, eight triples, 19 doubles, 71 runs, and 28 stolen bases.

Coffey was back to manage the Des Moines club in 1918 but it was destined to be an abbreviated season. Larger forces than professional baseball were at work. World War I and the concomitant “work or fight” order was wreaking havoc with minor league rosters and with attendance. Most minor leagues decided to truncate their seasons. The Western League ceased operations on July 7, 1918. The Boosters were 36-31, in third place, and Coffey was hitting .267 when the season ended. The major leagues were having their own difficulties with the “work or fight” order. All of the big league teams had lost players to the draft or to jobs in “essential” industries. They were looking for players to fill their depleted squads. Coffey, at the age of 31, was unlikely to be drafted so the Detroit Tigers signed him to a contract on July 10, 1918.14 When Tigers second baseman Pep Young was out with an injury, Coffey filled in.

Coffey’s first game with the Tigers came on July 13 in Washington against the Senators. He went 0-for-3 in the Tigers 1-0 victory. Coffey’s last game for the Tigers came on August 3, also against the Senators. Overall, Coffey played in 22 games for the Tigers and hit .209 with two triples, four RBIs, and two stolen bases. He played well in the field, making five errors in 116 chances for a .957 fielding percentage. When Pep Young came back, however, Coffey became expendable. Old friend Dave Shean came to the rescue, indirectly. The 34-year-old Shean was the everyday second baseman for the first-place Boston Red Sox. He had rheumatism in his foot bad enough to cause doubt he would finish the season. Red Sox owner Harry Frazee had Eusebio Gonzalez on the bench but wanted a bit more insurance. When the Red Sox came to Detroit for a three-game set on August 6, a deal was made for Coffey.15 On August 10, Edward F. Martin of the Boston Globe reported that Coffey would join the Red Sox that day. He went on to say Coffey “played second base capably for the Tigers in the absence of Pep Young”.16

It was not at second base, but at third base, however, that Coffey would contribute to the Red Sox. He played 14 games at third and only one at second for the pennant winning team. He hit a lowly .159 with a homer and a double in 44 at-bats. He made two errors in 49 chances for a .959 fielding average. His best game at the plate came on August 21 against the St. Louis Browns at Fenway Park. Spitballer Allan “Dixie” Sothoron held the Sox to two hits through the first seven innings but one of the hits was a home run by third baseman Coffey in the fifth. Coffey hit what the Herald and Journal‘s Burt Whitman called “a funny home run …a whack which ordinarily would have been good for three bases and which Hooper or Speaker either would have caught or held to a double”.17 The speedy Coffey, however, turned it into an inside-the-park home run, only the second home run hit at Fenway Park in 1918.

Coffey played his last games as a major leaguer on September 2, 1918. (Due to the war, both the American and National League had agreed to end the season by September 2 and start the World Series on September 4.) Coffey played in both games of a doubleheader in New York against the Yankees. He played third in the first game, going 1-for-3 and second base in the second game, going 2-for-4. Coffey was on the roster for the World Series and it looked as though he might get to play when Dave Shean injured his hand fielding a ball during practice. A rainout on September 4, however, allowed Shean time to heal. Fred Thomas, who had played 44 games for the Sox in 1918, was on leave from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and held down the hot corner during the Series. Consequently, Coffey did not appear in the World Series but was voted a $300 share of the victors’ prize money.18

It was back to the Western League and the Des Moines Boosters for Coffey in 1919. The player-manager played 123 games at second base and led his team to a fourth-place finish, just four games over .500 (71-67). Coffey bounced back at the plate, however, hitting .306 with three homers, seven triples, 29 doubles, and 32 stolen bases. In 1920, Coffey became a part-owner of the Des Moines franchise and, U.S. Census records show, by 1920 he was a married man. He was renting a home in Des Moines with his wife, Lorraine, a Missouri native, who was five years his junior. No other information is known about Lorraine Coffey.

It was a disappointing season for the Des Moines club. The Boosters finished in last place, 33 games behind the league-leading Tulsa Oilers. Coffey did his part, however. The 33-year-old played in 137 of the team’s 151 ball games. He was leading the team in hitting at .385 in mid-June19 before settling at .290 with four homers, four triples, and 25 doubles. He could still steal a base, garnering 26 more thefts that year. The next year, in what would be his final season in Des Moines, Coffey could improve his team’s fortunes by only one place as the Boosters finished seventh in the eight-team circuit. Coffey hit .300 but played in only 95 games, his lowest total in the minors since 1910 (the shortened 1918 season excepted). He hit 23 doubles but no home runs, only two triples, and only five stolen bases.

At the end of the 1921 season, Coffey announced that he would not be back for 1922. On November 17, 1921, The Sporting News reported, “Folk all over the circuit [the Western League] view the passing of Coffey with much regret for there never was a more popular man in the league than the prematurely-gray boss of the Des Moines outfit”.20 Coffey was very popular with the players and the fans wherever he managed or played. After playing most of the previous 12 years in the West, Coffey was heading home.

On February 18, 1922, Fordham named Coffey and Billy Keane (Fordham Class of 1904) co-managers of the varsity baseball team.21 It was understood Coffey would manage the Rams only part of the time because he had also taken a player-manager position with the Hartford Senators of the Eastern League. Coffey was taking over a Hartford club that finished fifth in 1921, five games below .500 at 71-78. The veteran manager could coax only two more wins out of the Senators in 1922. They finished in sixth place at 73-76. In 1922 Coffey had his worst year in minor league ball. He hit only .231 and played in only 50 games.

As the Hartford skipper, Jack Coffey has the distinction of being Jim Thorpe’s last manager. Thorpe, 35, was signed by Hartford during the 1922 season. The aging star could still hit but his off-field activities became on-field problems. Coffey was forced to dismiss Thorpe for “indifferent play.” Coffey himself spent only one year in Hartford. The next year, Coffey again co-managed the Fordham baseball team but also was the player-manager for the Macon Peaches in the Class B South Atlantic League. The Peaches, who had started the 1923 season as the Charleston Pals, had won the Sally League championship in 1922. Coffey did not have much to work with, however, since most of the players were sold before the start of the 1923 season.22 It did not get any better as the seasoned progressed. Attendance dropped dramatically in Charleston and manager Coffey was “much handicapped by lack of funds.”23 The Pals had won only seven of 28 games when they moved to Macon. Coffey rebounded nicely at the plate, at least partly due, no doubt, to the lesser quality pitchers in this league. The 36-year-old Coffey played in 114 games, hitting .294 (on the worst hitting team in the league24) with 11 home runs (a career best), three triples, 30 doubles, and 53 RBIs. He also stole nine bases. Again, he lasted only one year with his team. In 1924, Coffey, who continued his co-managing duties at Fordham, was the player-manager for two teams in the Three-I League. He started the season with the Peoria (Illinois) Tractors and finished with the Decatur (Illinois) Commodores. He hit .270 in just 38 games for the two teams.

On New Year’s Day 1925, The Sporting News reported, “Jack Coffey, worthiest of managers and grandest of men in baseball, has made it positive he will not return”.25 It was his last season of professional baseball. Coffey had played for 11 teams in eight leagues over the course of 16 seasons. The scholarly Coffey referred to his baseball sojourn as “a prolonged series of peregrinations to points provincial.”26

In 1925, Jack Coffey returned to Fordham University to stay. He earned his law degree and was now the full-time, sole manager of the baseball team. During the summer of 1925, Coffey worked as a scout for old friend Jack Hendricks, who was now managing the Cincinnati Reds. Coffey scouted in the Eastern League as well as in the Pacific Coast League. In 1926, Coffey succeeded Frank Gargan as Graduate Manager of Athletics at Fordham. Coach Coffey held both positions until he retired in 1958.

While Coffey was in charge of athletics at Fordham, the University became a national sports powerhouse. The baseball team won five Eastern Collegiate Conference championships and 14 Metropolitan Conference titles. Coffey’s career winning percentage as a Fordham manager is above the .700 mark.27 So popular was the baseball team it could draw 12,000 people to the Polo Grounds for games against Manhattan or Columbia. During the 1920s, 1930s, and into the 1940s, Fordham was a perennial football power. Fordham football games were extremely popular as well. Games against New York University would be played before more than 70,000 people at Yankee Stadium. Two Fordham teams, 1929 and 1937, went undefeated. The once-beaten teams of ’35 and ’36 included Vince Lombardi, whom Coffey had persuaded to come to Fordham in the fall of 1932.28 Lombardi’s first brush with fame came as one of the “Seven Blocks of Granite,” as the ’36 Rams football line was called. Fordham football teams also made two bowl appearances, the 1941 Cotton Bowl and the 1942 Sugar Bowl (back when an invitation to a bowl game was a rare event). Fordham also produced quality basketball teams and track stars during Coffey’s tenure.

By the 1950s the awards and accolades started to accumulate. In 1953, Coffey received a citation for “long and meritorious service to sports” from the Sports Broadcasters Association. In 1954, he was elected to the Collegiate Baseball Hall of Fame. On April 3, 1954, Fordham University renamed its baseball field Jack Coffey Field, which it remains to this day. Also in 1954, Coffey was named to the Helms Foundation Collegiate Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1958 the Eastern College Athletic Conference awarded Coffey its annual James Lynch Memorial Award for outstanding service over a long period. By 1958, though, Coffey had passed the mandatory retirement age at Fordham and the 71-year-old made plans to retire at the end of the spring semester. May 17, 1958, was Jack Coffey Day at Fordham (it was actually the second Jack Coffey Day; Fordham had honored him with a day on May 17, 1947, for his 25 years as manager of the baseball team). The The 1958 Day’s events began with a baseball game against Manhattan College at Jack Coffey Field. The Rams prevailed, 14-7. A reception followed the game and a dinner was held that night. Among the 500 guests were Frank “The Fordham Flash” Frisch, Hank Borowy, Johnny Murphy, and sportswriter Tom Meany. The president of Fordham, the Very Rev. Laurence J. McGinley, SJ, announced the creation of the John F. Coffey Award, a medal given each year to the Fordham varsity athlete who achieves the highest academic standing. Father McGinley also announced that the title Graduate Manager of Athletics would be Coffey’s forever and would be retired in his honor. In 1966, Coffey was elected to the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame.29 In 1970, he was in the inaugural class of inductees in the Fordham Hall of Fame.

Jack Coffey had been associated with Fordham for more than 50 years. He was an institution at the university. He mentored countless baseball players at Fordham, teaching them not only the technical aspects of the game but also how to play the game with class. At least 23 of his baseball charges made it to the major leagues, among them Hank Borowy, who won World Series games with the Yankees and the Cubs; Johnny Murphy; Babe Young; and Sam Zoldak. To his friends and associates he was Genial Jack, Mr. Fordham, or Mr. Birthday, the latter sobriquet given to honor Coffey’s prodigious memory. Sportswriters at the time claimed Coffey could remember the birthdays of 3,000 people. He was in the habit of addressing people by their birthday instead of by name, as in “Hello, Mr. July 30.” Coffey, an autodidact in foreign languages, was fluent in French (he wrote a sports column, in French, for “Fordham France”30), Spanish, Italian, and German. From at least 1929 until his retirement, Coffey traveled widely with his second wife, Anastasia. The two traveled to France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Alaska, Australia, and South America, among other places where Coffey would hone his language skills. At the end of his life, Coffey was suffering from arteriosclerosis and was confined to a nursing home. He succumbed to a heart attack on February 14, 1966. He was survived by his wife, Anastasia. The couple had no children. Coffey is buried at Calvary Cemetery, Queens, New York.

At Jack Coffey Field at Fordham a bronze plaque, placed there April 3, 1954, is inscribed: “To John F. “Jack” Coffey, A true sportsman, scholar and Christian gentleman.”

These are fitting words and a lasting testament to an exemplary person, baseball player, coach, and teacher.

Acknowledgement

The author gives special thanks to Patrice M. Kane, Head, Archives and Special Collections at the Fordham University Library. Ms. Kane kindly donated her time and resources, providing the author with invaluable information about Jack Coffey.

Sources

Websites

www.baseball-reference.com

www.sabr.org

www.minorleaguebaseball.com

Books

Waterman, Ty and Mel Springer, The Year the Red Sox Won the Series. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999.

Newspapers

Boston Globe

Boston Herald and Journal

Boston Post

Fordham Ram

Hartford Courant

New York Mirror

New York Times

New York World-Telegram and Sun

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Daley, Arthur. “Sports of The Times,” New York Times, May 12, 1958, p. 34.

2 Adams, Caswell. “Through the Years…,” Fordham Ram, May 17, 1947, p. 2.

3 Gilleran, Ed. “Looking Them Over,” Fordham Ram, May 17, 1947, p. 3.

4 Daley, op. cit.

5 Boston Globe, June 23, 1909, p. 5.

6 Boston Globe, July 9, 1909, p. 5.

7 Cooper, Arthur D. Boston Post, July 8, 1909, p. 10.

8 “Doves Showing a Much Better Frame of Mind,” Boston Globe, July 27, 1909, p. 4.

9 Boston Herald and Journal, July 27, 1909, p. 4.

10 Daley, op. cit.

11 Norton, Russell, F. “Baseball Above the Clouds,” Baseball Magazine, February 1912, Vol. VIII, No. 4, pp. 27-33.

12 “Coffey to Succeed Hans Wagner,” New York Times, September 21, 1914, p. 8.

13 Niely. “Coffey Remains with Denver,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1915, p. 8.

14 Boston Globe, July 11, 1918, p. 4.

15 Wood, Allan. Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox, Lincoln, Nebraska, Writers Club Press, 2000, p. 210.

16 Martin, Edward, F. Boston Globe, August 10, 1918, p. 4.

17 Whitman, Burt, Boston Herald and Journal, August 22, 1918, p. 4.

18 A full share was $1,108.45, the smallest amount ever awarded to a World Series winner. Wood, op. cit., p. 342.

19 The Sporting News, June 17, 1920, p. 3

20 The Sporting News, November 17, 1921, p. 2

21 “To Coach Fordham Nine,” New York Times, February 18, 1922, p. 16.

22 The Sporting News, December 21, 1922, p. 8.

23 The Sporting News, May 10, 1923, p. 2.

24 The Sporting News, November 8, 1923 p. 6.

25 The Sporting News, January 1, 1925, p. 3.

26 Daley, op. cit.

27 Solomon, Burt, Fordham University Press Release, May 19, 1958.

28 Cohane, Tim. Bypaths of Glory: A Sportswriter Looks Back, New York: Harper and Row, 1963, p. 4.

29 www.abca.org/downloads/pdf/ABCA_HallOfFamers.pdf

30 www.fordham-tradition.org/SEP96.HTM

Full Name

John Francis Coffey

Born

January 28, 1887 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

February 14, 1966 at Bronx, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.