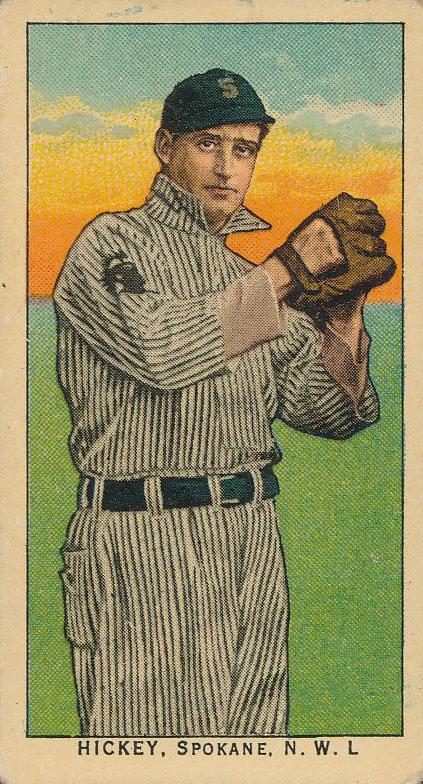

Jack Hickey

To curb the contract jumping that was commonplace during the 19th century, the National Commission, a three-person committee, was established to oversee Organized Baseball. The Commission was created by the National Agreement of 1903, which gave it the power to interpret and carry out the terms and provisions of the Agreement, including mediating contract disputes between players and teams.1 One player who became very familiar to the Commission was Jack Hickey. Early in his career he had a habit of signing whatever contract was put before him, regardless of any previous obligations, and seemed content to let the Commission sort out his status nearly every year.

To curb the contract jumping that was commonplace during the 19th century, the National Commission, a three-person committee, was established to oversee Organized Baseball. The Commission was created by the National Agreement of 1903, which gave it the power to interpret and carry out the terms and provisions of the Agreement, including mediating contract disputes between players and teams.1 One player who became very familiar to the Commission was Jack Hickey. Early in his career he had a habit of signing whatever contract was put before him, regardless of any previous obligations, and seemed content to let the Commission sort out his status nearly every year.

Although he struggled with control during his whole career, talented left-handed pitchers are always in demand, and multiple teams continued to compete for Hickey’s services. After he signed six separate contracts for the 1903 season, one report summed things up by saying, “If he wasn’t able to deliver, he wouldn’t get all these flattering offers.”2 At one point he was even called “a veritable ‘Rube’ Waddell, lacking, however, ‘Rube’s’ bad habits.”3 Despite his promise, Hickey appeared in only two major-league games, but he did carve out a successful minor-league career, mostly in the Pacific Northwest, twice winning 20 games.

After he retired, a brief story in the Seattle Star aptly summed up his career. “Hickey wasn’t eccentric like the average southpaw, but was a well set-up fellow, and how he could burn the leather apple over the plate. When he was right, he was unbeatable. It’s a funny thing about Hickey however, that as great as he was on the Coast, he didn’t get by in the majors while others of lesser ability did. That’s one of those things that happen in baseball.”4

John William Hickey was born November 3, 1881, in Minneapolis. His parents were John Hickey, a day laborer, and Elizabeth “Lizzie” (née Lynch), both born in Ireland. Young John, who went by “Jack” most of his life, was the third of their seven children. Older brother Edward and older sister Julia were followed by four younger sisters: Kate, Lizzie, Mamie, and Bridget.

No information about Hickey’s early life has surfaced to date, but his known pitching career started with the Minneapolis Brewing Company in 1900. He struck out 19 in a 4-2 win over the Minneapolis Grays in a game umpired by Walter Wilmot, captain of the Minneapolis Millers, “for the sole purpose of getting a line on Hickey’s work…Wilmot is now trying to sign Hickey for next year.”5 Hickey pitched for a semipro team in Madison, South Dakota later in 1900, but that fall it was reported that he had been signed by Minneapolis.6 However, by the following spring he had been signed by George Lennon of the St. Paul Saints.7 Before playing for either team in his home state, he signed with still another team for 1901, the Seattle Clamdiggers of the Pacific Northwest League.8

At the same time Hickey was fielding offers from Louisville and Kansas City, but he returned to South Dakota in the spring of 1901. He remained in South Dakota until July, at which time he reported to Seattle. He was under contract with Seattle for 1902, but that March he and catcher Ralph Frary jumped the club for an independent team in Sacramento, California, having “been offered flattering inducements.”9 He returned to Seattle in May, apparently in the good graces of team owner Dan Dugdale, and had an excellent season.10 It was so good that in November he was signed by the American League’s Cleveland Bronchos (which took the name Naps beginning with the 1903 season).11 Later it was revealed that Hickey also signed with Connie Mack of Philadelphia for a $200 advance, but returned the money when Cleveland came through with a better offer.12

A couple of months later Hickey had a change of heart and promised to return his advance money to Cleveland manager Bill Armour. One factor may have been that he married Beulah Burrows, a native of Seattle, on January 17, 1903. A brief note of the marriage said, “His friends now think the young lady who is now Mrs. Hickey had something to do with causing Jack to change his mind.”13 He remained in Seattle, but Dugdale refused to provide advance money (presumably to repay Cleveland). After what was described as, “a wordy battle in a downtown cigar store”14 between the two, Hickey signed with a rival, the Seattle Siwashes of the outlaw Pacific National League, for the 1903 season.

Meanwhile, Cleveland had heard nothing from Hickey, nor had that team’s $300 advance been returned. Hickey, who apparently had spent the advance and was strapped for funds, was quoted as saying he would repay Cleveland “when he earned it.”15 Cleveland club officials then secured an attorney in Seattle who filed an injunction preventing Hickey from playing for Seattle on the grounds that he had signed an “ironclad personal contract,” not the standard player contract with the 10-day reserve clause.16

By mid-April Hickey was on the move again, jumping the Seattle Siwashes to return to Dugdale and the Chinooks. By one count, this was the sixth contract signed by Hickey; he was starting to get some criticism in the local press. One report called his continued jumping “rubber leg actions,”17 and another called Hickey a “champion hop-skip-jumper.”18 All was soon forgotten when he threw a one-hit shoutout in his first game for Seattle.19 He went on to win 21 games for the Chinooks. After the season, his contract status was finally resolved when Garry Herrmann of the National Commission awarded him to Cleveland.20

Hickey showed well in Cleveland’s spring training camp in San Antonio in 1904, displaying “plenty of speed and curves.”21 He made the club’s opening day roster. The 5-foot-10, 170-pound lefty made his major-league debut against the White Sox at South Side Park in Chicago on April 16 under difficult conditions. The actual game time temperature was not recorded but said to be “dancing below the freezing mark.” The 5,000 fans in attendance were “all muffled up in sweaters, overcoats, and fur caps.”22 Perhaps partly because of the cold weather, Hickey was wild, surrendering seven bases on balls. On top of that, his teammates committed three errors, two by right fielder Elmer Flick, and also made several baserunning mistakes to contribute to the 10-8 Naps loss. The game story remarked, “But for his wildness, which proved costly, Hickey has all the appearance of being a good twirler. Had he gotten the right kind of support he would have won his game with ease.”23

His next start was two weeks later, on May 4 against the Tigers at Bennett Park in Detroit. Hickey pitched much better, throwing four scoreless innings, but a single and two walks loaded the bases in the fifth. At that point Hickey was replaced by Addie Joss, who surrendered a bases-clearing triple to Tigers first baseman Charlie Carr. Although the base runners were Hickey’s responsibility, the 3-2 loss was charged to Joss.

A week later, in a move necessitated by Cleveland’s need to get down to the 16-man roster limit, Hickey was released and sold to the Columbus Senators of the American Association. He gladly accepted the demotion, saying, “When I am getting plenty of work, I am not wild as I was in Chicago and Detroit. The more work I am given the better I am and if Columbus will let me pitch twice a week, they will not be sorry. I would certainly rather be in the game in a minor league than warming the bench in the big league, so I am tickled to death with the change.”24

Hickey went 15-10 in 31 games for Columbus; in August Cleveland planned to recall him. It was then revealed that the earlier transaction was not a sale but rather a “farming,” with Cleveland still holding his contract rights. Citing a conflict with manager Armour, Hickey refused and instead returned to Seattle to finish the season with the Siwashes. In October he signed a “personal agreement” with manager Russ Hall of Seattle for $250 a month.

He reported to the Seattle train depot for a road trip to Oakland, but Hall would not let him board the train unless he also signed a standard player contract. Because that would make him subject to release by the club, Hickey refused and did not travel with the team. When he did not show up in Oakland, Hall claimed that he was in violation of the original agreement and refused to pay him.25 Hickey then retained legal counsel and sued the Seattle club for $241.65.26 The club initially offered to settle with him for $100. Hickey finally agreed to $154, and the case was dismissed.27

Cleveland still held his contract rights, but after what he felt was unfair treatment in his two-game trial during the prior season, Hickey vowed that he never would play for them again. He softened his stance somewhat when he learned that Napoleon Lajoie was taking over as manager from Bill Armour, but in May the Naps sold him outright to Columbus. A couple of weeks later Columbus traded him to Milwaukee, where he finished the 1905 season. Considered the best left-hander in the American Association, he won 21 games combined with the two clubs.

Hickey returned to Milwaukee in 1906 but in June once again jumped his contract. One report alluded to a disagreement between him and manager Joe Cantillon28 – but another shed more light on the reason for his departure. He left the Brewers right before a scheduled road trip to Columbus, and one newspaper reported, “It is rumored that creditors in Columbus and Minneapolis were too actively on his heels and he didn’t have the nerve to come to Columbus again.”29 Regardless of the true reason, he returned to Seattle for a bit before being claimed on waivers by his third American Association team, the Indianapolis Indians, where he finished the season.

Whether it was in Organized Baseball or the outlaw leagues, Hickey always wanted to pitch nearer Seattle, where he had begun his professional career and had come to make his offseason home (likely influenced by his wife’s roots there). In the spring of 1907, he finally got his wish. After clearing waivers, he was sold to the Aberdeen (Washington) Black Cats of the Class-B Northwestern League.30 Injuries and wildness limited him to an 8-8 record in 17 games and the next year he was on the move again, splitting the 1908 season between Vancouver and Spokane. Back with Vancouver in 1909, he showed some of his former ability by throwing a no-hitter in a 1-0 loss to Tacoma on April 25.31 He struggled through the rest of the season, posting a 10-22 record.

Hickey was traded to Spokane that offseason.32 He was released in June 1910, however, after appearing in just two games.33 He resurfaced with Edmonton (Alberta) of the Western Canada League later that season, winning 10 of 13 decisions. It was then reported that he had been signed by Davenport (Iowa) of the Three-I League for 1911. He never reported, telling team officials he was retiring from baseball to take a job in the courthouse in Seattle.

By 1912 Hickey was working as a deputy sheriff in King County (Seattle) and later as a bailiff. He continued to pitch semipro ball on the weekends and participate in old-timers events. He also umpired in the Northwestern League during the 1915 and 1916 seasons. By the time of the 1920 US Census, he and his wife Beulah had three children, daughters Jane and Maxine and son John. The family was living with his in-laws in Seattle and Jack was working as a steamfitter in the shipyards. By 1923 he was “in charge of the ice-making and general conduct of the [ice hockey] rink in Seattle.”34 Jack listed his marital status as divorced on the 1930 census, which recorded him as working as a laborer in the Chemtech industry.

In 1937 Hickey suffered a stroke, leaving him bedridden. He was confined to Zenith Sanatorium. Prior to his illness, he had been active in the Seattle chapter of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players. Former teammates and friends kept busy “caring for Jack” during his confinement.35 Four years later, he suffered a series of additional strokes. These led to his death on December 12, 1941, at 60 years of age. He was survived by his three children. After services at the Church of the Immaculate, he was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Seattle.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Russ Walsh.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics from Hickey’s playing career are taken from Baseball-Reference.com and genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com. The author also used information from clippings in Hickey’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/National_Agreement

2 “All About Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, March 29, 1903: 17.

3 “Expects Much of Youngsters,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 13, 1903: 14.

4 “Reminiscences of D. E. Dugdale,” Seattle Star, March 1, 1923: 14

5 “Wilmot and Hickey,” Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Argus Leader, September 26, 1900: 5.

6 “Sporting Notes,” St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, November 3, 1900: 6.

7 “Sioux City Will Stay,” St. Paul Globe, February 22, 1901: 6.

8 “Our Team,” Seattle Daily Times, April 19, 1901: 16.

9 “Baseball Players Gone,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, March 15, 1902: 3.

10 No individual pitching records were found in Baseball-Reference or league newspapers.

11 “Has Signed Cleveland Contract,” Seattle Daily Times, November 24, 1902: 16.

12 “All About Baseball.”

13 “Jack Hickey Married,” Tacoma News Tribune, January 24, 1903: 17.

14 “Two Twirlers Have Jumped,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1903: 6.

15 “Injunction Against Hickey,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 28, 1903: 6.

16 “Injunction Against Hickey.”

17 “Crowd Divided in Baseball,” Spokane Chronicle, May 8, 1903: 10.

18 “General Sporting News,” Mansfield (Ohio) News Journal, December 8, 1903: 7.

19 “Jack Hickey’s Wonderful Work,” Seattle Star, May 11, 1903: 1

20 “Baseball,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 30, 1903: 9.

21 “Youngsters Are Signing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 29, 1904: 9.

22 “Chilly Blasts Froze Players,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 17, 1904: 22.

23 “Chilly Blasts Froze Players.”

24 “Jack Hickey Has Been Released,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 11, 1904: 8.

25 “Local Magnates Try to Play Smooth Trick on Jack Hickey,” Seattle Daily Times, November 5, 1904: 12.

26 “Hickey Sues for Salary,” Seattle Daily Times, December 27, 1904: 9.

27 “Hickey Case,” Spokane Chronicle, January 17, 1906: 5.

28 “Hickey Leaves Brewers,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, June 9, 1906: 13.

29 “Hickey Hurdles Milwaukee Club,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, June 6, 1906: 11.

30 “Tacoma 1; Vancouver 0,” Seattle Daily Times, April 26, 1909: 11.

31 “Star Pitcher Is Signed,” Portland Oregonian, March 31, 1907: 3.

32 “Jack Hickey Signs Roll,” Spokane Press, March 3, 1910: 9.

33 “Jack Hickey Was Released,” Wenatchee (Washington) Daily World, June 9, 1910: 6.

34 “Veteran Baseball Men Helping Keep Ice Hockey Going,” Seattle Daily Times, November 4, 1923: 24

35 “Loyal Pals,” Seattle Daily Times, April 11, 1940: 32.

Full Name

John William Hickey

Born

November 3, 1881 at Minneapolis, MN (USA)

Died

December 28, 1941 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.