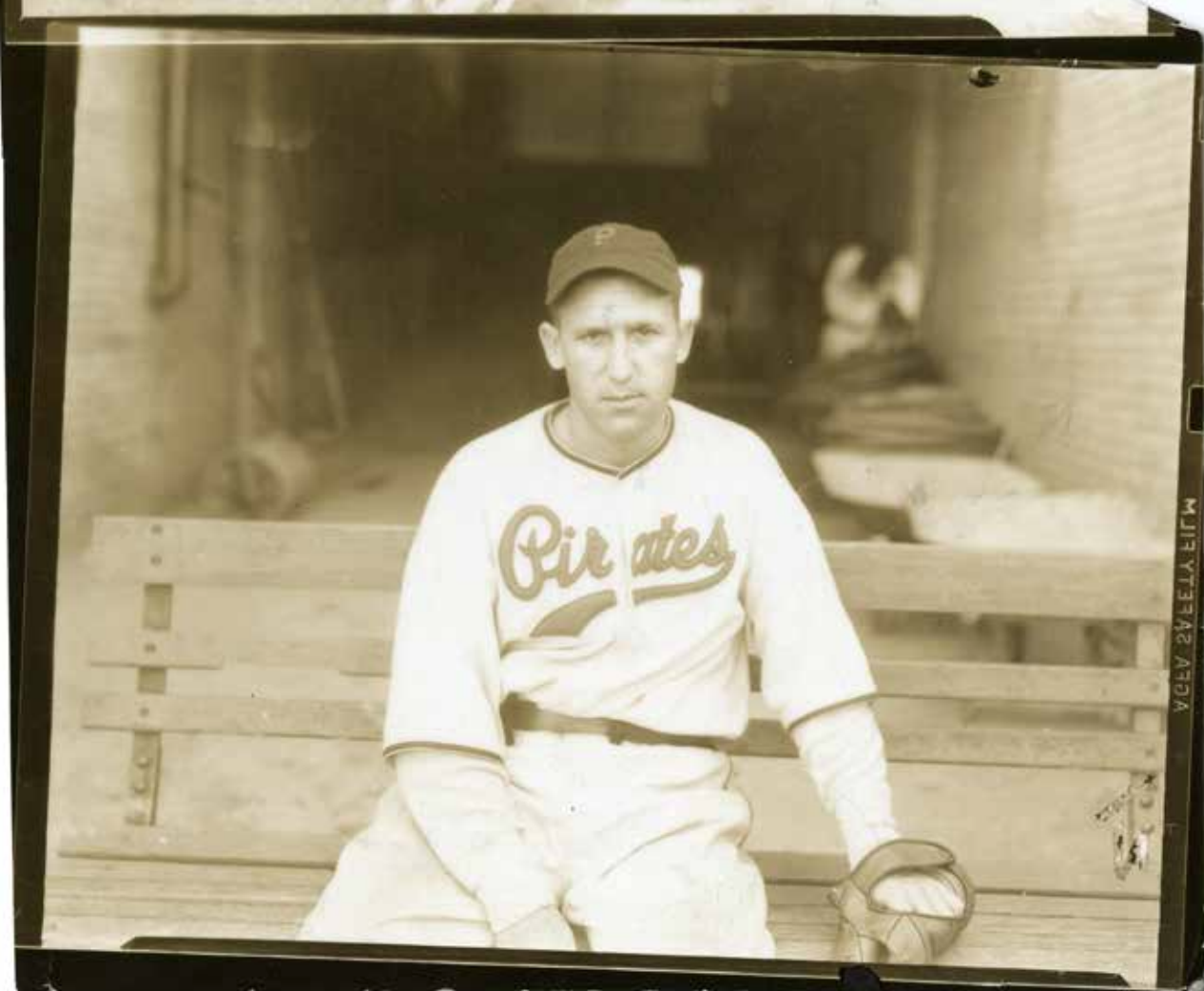

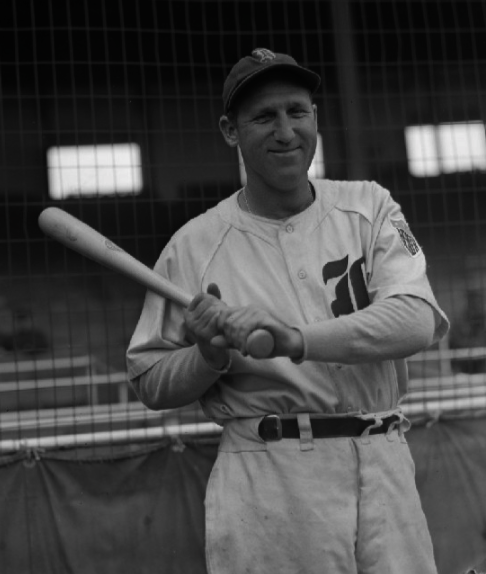

Jim Tobin

No one confused portly right-hander Jim Tobin with hard-throwing contemporaries like Bob Feller, Johnny Vander Meer, or Hal Newhouser. “Tobin’s fast ball could not break a pane of glass,” opined sportswriter Arthur Daley in the New York Times. “He has two pitches — slow and slower. … He is the most tantalizing gent on the mound in all baseball.”1 But that wasn’t always the case. Tobin suffered a severe shoulder injury in 1939 that jeopardized his career. Cast off by the Pittsburgh Pirates, “Old Ironsides” emerged with the lowly Boston Braves as one of the era’s best knuckleballers. Over a four-year stretch (1941-44) he completed 100 of 125 starts, posted a misleading 56-66 record, and tossed a no-hitter. He was also a threat at the plate. In 1942 he belted three homers in one game, the only hurler in modern history to accomplish the feat. Known for his prickly personality, Tobin was out of the major leagues after the 1945 campaign even though he was seemingly at the height of his career.

No one confused portly right-hander Jim Tobin with hard-throwing contemporaries like Bob Feller, Johnny Vander Meer, or Hal Newhouser. “Tobin’s fast ball could not break a pane of glass,” opined sportswriter Arthur Daley in the New York Times. “He has two pitches — slow and slower. … He is the most tantalizing gent on the mound in all baseball.”1 But that wasn’t always the case. Tobin suffered a severe shoulder injury in 1939 that jeopardized his career. Cast off by the Pittsburgh Pirates, “Old Ironsides” emerged with the lowly Boston Braves as one of the era’s best knuckleballers. Over a four-year stretch (1941-44) he completed 100 of 125 starts, posted a misleading 56-66 record, and tossed a no-hitter. He was also a threat at the plate. In 1942 he belted three homers in one game, the only hurler in modern history to accomplish the feat. Known for his prickly personality, Tobin was out of the major leagues after the 1945 campaign even though he was seemingly at the height of his career.

James Anthony Tobin was born on December 27, 1912, in Oakland, California, the second of three sons born to Richard John and Hannah “Annie” (O’Leary) Tobin. Both of his parents were born in Ireland, immigrated to the United States in the first decade of the twentieth century, and married around 1910. Richard found work in Oakland street-car system, moving up from trackman to foreman. The Tobins resided in the eastern part of city, where Richard Jr., Jim, and youngest son Jackie were introduced to baseball on local sandlots. (Jackie also had a long career in Organized Baseball, spending 1945 with the Boston Red Sox as an infielder.)

Given his short, stocky size as a youth, Tobin often played catcher. He eventually shed the tools of ignorance as a member of the baseball team at Roosevelt High School and began concentrating on pitching. A growth spurt added seven inches onto his frame by the time he graduated in 1931, transforming Tobin into a rugged 6-foot, 175-pounder with an intimidating presence on the mound.

Tobin’s trek to the big leagues started in 1931 at a baseball school and tryout camp sponsored by the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. The 18-year-old impressed the brass enough to earn a contract and assignment to the Bisbee Bees in the Class-D Arizona-Texas League the following year. Tobin won nine of 11 decisions before the league disbanded in late July. Unclaimed by the Oaks, Tobin returned to Oakland and hurled in semipro circles, where he caught the attention of Bill Essick, a superscout for the New York Yankees whose signees included Lefty Gomez and Joe DiMaggio.2 On Essick’s recommendation, the Yankees signed Tobin.

Tobin’s four seasons in the Yankees’ farm system were marked by success and increased frustration as he moved up the ladder. He spent most of the 1933 campaign with the Wheeling Stogies in the Class-C Mid-Atlantic League and earned a late-season promotion to the Binghamton Triplets in the Class-A New York-Penn League. A 15-10 slate for Binghamton in 1934 moved Tobin up another notch to Oakland, where he began the next season with the Oaks, just a step removed from his dream. The Sporting News described the hurler as a “lively, young, all-around prospect [who] gains as much praise for his batting and utility work as for his hitting.”3 The paper also noted Tobin’s free-for-all spirit, which would eventually characterize his relationship with all the big-league teams he played for. “[Tobin’s] lack of seriousness was regarded as a defect and he was constantly warned that he never would succeed.”4

A knee injury limited Tobin to just 23 appearances and an 11-8 record in 1935 with the Oaks, but the Yankees thought enough of him to add him to their 40-man roster. Had Tobin not required an appendectomy, he would have been at the Yankees’ spring training in 1936. The now 23-year-old, who proudly called himself the “Mighty Tobin,” responded with his best season in Organized Baseball in 1936 (16-8 and 230 innings) with the Oaks.5 He also regularly pinch-hit and occasionally played first base, producing a .261 batting average in 153 at-bats.

Tobin arrived at the Yankees’ spring camp in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1937 with a chip on his shoulder. Rooming with former Bay Area prodigy and budding superstar DiMaggio, Tobin clashed with George Weiss, the director of the Yankees farm system, and especially manager Joe McCarthy, who, according to sportswriter Dan Daniel, considered Tobin “more clown than pitcher.”6 “The Yankees had a lot of fine pitching in 1937,” said Tobin, “and I did not get, maybe did not warrant, great attention.”7 But when the Yankees optioned him to the Newark Bears in the International League, Tobin balked, returned home to Oakland, and threatened to quit baseball altogether. The Yankees blinked first and sold him to the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 14, less than a week before the regular season started. “If you keep trying, fighting, it all comes out in the wash,” said Tobin in what could pass as his personal motto.8

If Tobin was frustrated with McCarthy, he must have been livid with Pirates manager Pie Traynor, who installed the hurler at the far end of the bench. Tobin tossed a scoreless inning of relief in his debut on April 30, then did not pitch again until May 31, when he picked up the win in a sloppy four-inning relief outing (three runs and five walks) in the second game of a doubleheader against Cincinnati. By the end of August, Tobin, sporting a miserable 6.10 ERA in only 31 innings, seemed destined for the minors before emerging in what Pittsburgh sportswriter Charles J. Doyle called a “blaze of victories.”9 Beginning with a four-hitter against the Reds in the second game of a twin bill on September 8, Tobin tossed six consecutive complete games, winning five of them and yielding just eight earned runs in 54 innings (1.33 ERA) to conclude his rookie season as the hottest pitcher in baseball.

In 1938 Tobin arrived at the Pirates’ spring training in San Bernardino, California, brimming with confidence, which swelled following complete-game victories in his first two starts in the season. Pittsburgh sportswriter Les Biederman reported that Tobin worked closely with pitching coach Johnny Gooch, who changed his motion to a more overhand delivery in order to conceal his pitches.10 The Pirates would “sink or swim,” opined Doyle, with a core of young and relatively inexperienced hurlers, including Bob Klinger, a rookie; Tobin and Ross Bauers, beginning their second full seasons; and third-year speedballer Cy Blanton.11 After treading water through May, the Pirates began swimming a 4×100 relay. On June 15 Tobin tossed the first of his 12 career shutouts by blanking the league-leading New York Giants on five hits at the Polo Grounds. A month later, on July 14, he relieved Blanton to start the ninth and hurled three hitless innings to earn the victory against the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field and push the Bucs into first place. In what the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette called a “sensational” performance, Tobin gave the Pirates yet another emotional lift by tossing 11 scoreless innings of relief to beat the Boston Braves in the first game of a doubleheader on July 24.12

The surprise team of baseball, the Pirates seemed primed to capture their first pennant since 1927. Tobin’s shutout on September 22 as part of a doubleheader sweep at Ebbets Field maintained the Pirates’ 3½-game lead in a fierce race with the Chicago Cubs. “My mother could manage the Yankees and win a pennant,” said an indignant Tobin, his sights already set on facing his former tormenter McCarthy in the World Series.13 And then the bottom fell out. The Pirates lost seven of their final 10 games, and the Cubs won 11 of 13, punctuated by Gabby Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’” against the Bucs at Wrigley Field on September 28. Tobin lost his last three starts, but was hardly to blame. They took place in a six-day stretch, the final two coming on one and two days’ rest, to end a disappointing season with a team-high 14 victories and a sturdy 3.47 ERA in 241⅓ innings.

Tobin’s 1939 campaign started with a holdout during spring training and got worse as the season commenced. The stubborn hurler clashed with skipper Traynor about staying in games, and their relationship turned toxic. While the Pirates struggled to play .500 ball, Tobin suffered a wrenched back and injured his shoulder in a wild head-first slide trying to stretch a single into a double against the St. Louis Cardinals on July 9.14 The injury proved much more debilitating than expected, and was indeed career-altering. Tobin, who had hurled inconsistently even before the mishap, made only seven more appearances and landed on the disabled list twice, finishing with a disappointing 9-9 slate and a 4.52 ERA in 145⅓ innings. The Pirates won just 23 of their final 69 games, a noteworthy collapse that Smoky City sportswriter Havey Boyle attributed to the “crumbling pitching staff.”15 Injuries to Tobin, moundmates Bauers and Bryant, and outfielder Johnny Rizzo, coming off a productive rookie season (111 RBIs), as well as down seasons by All-Stars Arky Vaughn and Lloyd Waner, contributed to the Pirates’ worst season since 1917. The clubhouse was rife with tension, with players openly questioning Traynor, who was fired at season’s end. Tobin was widely seen as one of the instigators of the unrest. His days as a Pirate seemed numbered when hard-nosed Frankie Frisch was named manager and promised a more disciplined club. On December 6 the Pirates sent Tobin along with cash to the Boston Braves for starter/reliever Johnny Lanning.16

Tobin joined the Braves, a perennial second-division team, at their spring training facility in Bradenton, Florida, but noticed that something was horribly wrong. “I found that my arm hurt every time I tried to put something on a pitch.”17 He abandoned his fastball, curve, and occasional screwball and transformed himself into a soft-tossing knuckleballer. “I had been fooling around with the pitch for years,” said Tobin, “[but] did not use it in competition.”18 Now it became a necessity to salvage his career. Less than a week before the season commenced, Tobin slipped while fielding a bunt on a wet infield during an exhibition game against the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium on April 11 and tore ligaments in his knee.19 Sidelined for 3½ months, Tobin debuted for skipper Casey Stengel’s club on July 27, tossing two hitless innings of relief against the Pirates at Braves Field. After getting rocked in his first start, a week later (seven runs in three innings), in a loss to the Reds, Tobin completed nine of 10 starts, winning six of them. He concluded the season by holding the Giants to two hits over seven scoreless innings of relief to earn his seventh victory and lowered his ERA to 3.83 in 96⅓ innings for the seventh-place Tribe.

Tobin’s late-season success raised the ante in 1941. Once called the “Rock of Gibraltar” by Boston sportswriter Howell Stevens as much for his husky frame as for his unflappable presence on the mound, Tobin unexpectedly struggled while opponents teed off on his flat knuckler.20 With a 2-4 record and 5.27 ERA, Tobin was relegated to mop-up duty in June and fared no better. “Jim was pitching for his job,” suggested beat reporter Jack Malaney when he took the mound in the second contest of a July 4 twin bill against the Philadelphia Phillies in Boston.21 Ignoring rumors of his imminent trade or demotion to the minors, Tobin responded with a gem, a two-hit shutout, to commence what Howell Stevens described as “one of the most astounding” pitching stretches in recent Braves history.22 Tobin, whom the Boston press playfully called Abba Dabba and Shamus (a nod to his Irish descent), as well as Old Ironsides, completed 17 of 18 starts with a stellar 2.27 ERA in 174⅓ innings. In the only start he didn’t complete, Tobin hurled 12 innings of one-run ball against Cincinnati at Crosley Field; it was also the fourth time he tossed at least 10 innings during that stretch. While Malaney gushed that Tobin’s performance “placed him on a footing with any pitcher in the league,”23 Howell noted that his knuckleball was the “deadly poison” that killed batters in their tracks.24 The Braves finished in seventh place, but Tobin, who completed 20 of 26 starts and finished with a 12-12 record, was a beacon of hope on an otherwise dismal staff.

After some initial tribulation, Tobin’s mastery of the knuckler in 1941 drew comparisons to other knuckleballers, such as longtime Giant Freddy Fitzsimmons, then with the Dodgers, the Senators’ Dutch Leonard, and the White Sox’ Ted Lyons. “My knuckler … floats,” Tobin, who did not go into a full windup, said a few years later. “It breaks a couple of ways certain days better than others. To be at its best, the knuckleball should be pitched into the wind. Then it does strange pranks. To make a knuckleball effective, you have to pitch it low; get it high and hanging, and you are murdered.”25 Abba Dabba wasn’t exaggerating: On 23 occasions in his last five seasons, he gave up at least 12 hits in a game.

Tobin captured the hearts of the Braves faithful with his knuckler. “It’s not only a tough pitch to hit but also to describe,” noted catcher Ray Berres, Tobin’s teammate on the Pirates and Braves. “From the stands it looks like Tobin can’t get away with that kind of slow stuff for more than three innings. But when you’re up there hitting, you see it wave and dance like a butterfly or a piece of cardboard in the wind.”26

Even umpires were impressed with the tricks Tobin’s knucklers performed. Veteran umpire Bill Stewart recounted an embarrassing situation one time when he was certain a Tobin knuckler would be high and inside. “I’ve never in my life seen a ball break and dart downward over the plate as that one did,” said Stewart. “I yelled ‘Ball — Strike,’ then blushed,” confusing both the batter and Tobin.27

Tobin overcame a nagging strain to his Achilles tendon in 1942 spring training to fashion a complete-game victory against the Phillies in his debut on April 15. He added another chapter to his growing list of accomplishments by socking a two-run homer, his first as a Brave, and only the third in his career. Though he had been used as a pinch-hitter in his big-league career thus far, he was not yet known as one of the best hitting pitchers in baseball. But that quickly changed. On April 22 he whacked three more hits and mesmerized the Dodgers for 11 scoreless innings with knuckleballs described poetically by sportswriter Arthur E. Patterson as looking like a “cross between a grapefruit and a bean bag, with a bit of dead cod thrown in,” only to yield four tallies in the 12th and lose, 4-0.28

Three days after defeating the Phillies in a route-going outing on May 9 and collecting two more hits, Tobin walloped a pinch-hit home run in a loss to the Chicago Cubs at Braves Field. The next day, May 13, featured what Howell Stevens of the Boston Post considered “one of the most astounding feats of baseball history.”29 En route to a complete-game five-hitter against the Cubs, Tobin belted three consecutive home runs and drove in four runs in a 6-5 victory. While Fred Knight of the Boston Traveler described it as an “adjective-exhausting feat,”30 Jerry Nason of the Boston Globe wrote that Tobin “went absolutely berserk with the bat and with piledriving power” to become the first big-league pitcher to clout three round-trippers in one game since Guy Hecker of the Louisville Colonels in the American Association in 1886.31 Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune was impressed, too, musing, “[Tobin’s] bat was nothing short of terrifying.”32

Three days after defeating the Phillies in a route-going outing on May 9 and collecting two more hits, Tobin walloped a pinch-hit home run in a loss to the Chicago Cubs at Braves Field. The next day, May 13, featured what Howell Stevens of the Boston Post considered “one of the most astounding feats of baseball history.”29 En route to a complete-game five-hitter against the Cubs, Tobin belted three consecutive home runs and drove in four runs in a 6-5 victory. While Fred Knight of the Boston Traveler described it as an “adjective-exhausting feat,”30 Jerry Nason of the Boston Globe wrote that Tobin “went absolutely berserk with the bat and with piledriving power” to become the first big-league pitcher to clout three round-trippers in one game since Guy Hecker of the Louisville Colonels in the American Association in 1886.31 Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune was impressed, too, musing, “[Tobin’s] bat was nothing short of terrifying.”32

Despite Tobin’s exploits on the mound and at the plate, the Braves were a terrible team and finished in seventh place for the fourth consecutive season. Old Ironsides was a workhorse, leading the majors with 28 complete games (in 33 starts) and 287⅔ innings, with 12 victories but also 21 losses. When his knuckleball was fluttering, he seemed unbeatable, posting a 2.06 ERA in his victories compared with 4.76 in his losses. Then again, the Braves provided little support, scoring three runs or fewer in 19 of his 21 defeats, leading Stevens to lament that Tobin had been dogged by “cruel luck” all season long.33

Braves fans were buzzing when interim skipper Bob Coleman, who had replaced Casey Stengel (sidelined for two months with a broken leg), guided the club to a 14-8 start in 1943. That early-season success, however, was an aberration as the Braves “proved utterly lacking in offense,” wrote Malaney about the lowest scoring team in baseball.34 The pitching, on the other hand, Malaney suggested, was “one of the reasons why Boston’s fans [didn’t] entirely give up.”35 In his most consistent season, Tobin completed 24 of 30 starts en route to a 14-14 record while missing several turns in July with a leg injury. On June 26 he baffled the Giants with a knuckler that Gotham sportswriter Harry Cross described as “travel[ing] so slowly that it looked as big as a balloon when he reached the plate.”36 Tobin tossed a six-hitter to defeat aging Carl Hubbell, off whom he whacked a monstrous home run over the grandstand roof in the Polo Grounds.

On July 4 Tobin took revenge against Pirates manager Frankie Frisch, whom he held responsible for his banishment from the Pittsburgh club, by shutting out the Bucs, 13-0, collecting three hits, including a home run, and scoring three times. Tobin, described as “more of a home run threat … than any other member of the team,” even had a one-game tryout at first base to inject some pop into an anemic offense that hit only 39 round-trippers that season, including Tobin’s pair.37 But Abba Dabba’s floaters were more important to the club than his long balls. Reflecting on Tobin’s season, sportswriter Ken Smith quipped that the rotund hurler “drives managers to distraction with his slow knuckler.”38 Tobin (250 innings and a career-low 2.66 ERA) formed with Al Javery (17-16 with a big-league-most 303 innings), Nate Andrews (14-20 and a staff-best 2.57 ERA in 283⅔ innings), and Red Barrett (12-18, 255 innings) the most durable mound quartet in baseball.

Tobin’s future with the Braves appeared murky as the 1944 season got underway while World War II claimed the services of more and more ballplayers. Recently reclassified 1-A, Tobin was expected to report to Army basic training at any point, but that call never came. Tobin was almost unhittable in his first three starts, which took place over a nine-day span. After a tough-luck three-hit, 2-1 loss to the Giants, Tobin held the Phillies hitless for 5⅓ innings, settling for a one-hit shutout.

Against the Dodgers at Braves Field, Tobin needed only 98 pitches and 90 minutes to pitch the big leagues’ first no-hitter since St. Louis Cardinal Lon Warneke’s in 1941, and he also smacked a home run.39 Sportswriter Jerry Nason of the Boston Globe gushed that Tobin sent a “torrent of ‘butterfly’ pitches dipping, fluttering, and staggering across the plate” to mesmerize Dodgers hitters.40 Braves president and part-owner Bob Quinn was as excited as his players were. “It was one of the most intelligent games I ever saw pitched,” he told sportswriter Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor.41 “[Tobin] had good hitters like Dixie Walker, Augie Galan, and Mickey Owen looking foolish, waving their bats wildly and missing by two feet.”42 Tobin claimed his success was the result of throwing his knuckler side-arm to righties instead of overhand.43

Another no-hitter followed on June 22, albeit an abbreviated five-inning no-no against the Phillies that was called for darkness, but it was nonetheless Tobin’s fourth shutout in just over two months. Playing for the lowly Braves, second-class citizens even in Red Sox-crazy Boston, hardly afforded Tobin the kind of national notoriety he might have gotten had he played for a contender. But when St. Louis Cardinals hurler George Munger was summoned to the Army just days before the All-Star Game, Tobin was chosen to take his place, and joined teammates Andrews and Javery on the National League staff. Back at Forbes Field, but now on a national stage, Tobin tossed a 1-2-3 ninth in the NL’s 7-1 victory. Tobin fired complete-game victories in his first two starts after the midsummer classic, including tying his career longest game with a 14-inning outing against the Cubs in the first game of a twin bill on July 22 to improve his record to 11-10 and lower his ERA to 2.24. The Braves limped to another second-division finish in Coleman’s first full season as skipper, and Tobin was much less effective in the final 2½ months, during which his ERA almost doubled. He finished with a career-best 18 wins, with 19 losses, and once again led the majors with 28 complete games, and a sturdy 3.01 ERA in 299⅓ innings.

After an acrimonious contract dispute and late arrival at spring training, Tobin tossed a complete game and knocked in two runs in a 13-5 trouncing of the Giants in his 1945 season debut. The burly 32-year-old took his turn, often on two and three days’ rest, but was the last man standing of the pitching staff’s big four. Javery and Andrews were sidelined with injuries and Barrett had been traded to the Cardinals for three-time 20-game winner Mort Cooper, who went down with arm problems. While the Braves played .500 ball as late as July 21, the clubhouse was racked with tension and dissent. Tobin’s frustration mounted after he tossed six consecutive complete games in a 24-day stretch in July, winning just one despite a 2.15 ERA in 50⅓ innings. Tobin, whom sportswriter Jack Malaney considered “too outspoken” in his critique of the team and management, was finally seen as expendable and was sold to the Detroit Tigers in a waiver transaction on August 9.44

Suddenly on a team with pennant aspirations, Tobin let loose with a tirade against the Braves. “I was never happy in Boston,” he claimed. “You fought yourself dizzy … and you finished down in the dumps. [Losing] beats your brains out.”45 He saved his sharpest words for Braves president John Quinn, who saw Tobin as the root of the clubhouse problems: “Imagine accusing a man who has given what I had to the Boston ball club, of being the chief of a lot of jakes, the big bad wolf.”46

Tobin’s debut with the Tigers was “spectacular,” gushed Motor City sportswriter Sam Greene.47 In the first game of a doubleheader against the Yankees on August 12, Tobin hurled three innings of relief and blasted a three-run walk-off round-tripper in the 11th inning to emerge as a hero in front of more than 50,000 fans at Briggs Stadium. Cast in the role of swingman, Tobin posted a 4-5 slate (3.55 ERA in 58⅓ innings) as the Tigers, on the last day of the season, secured their first pennant since 1940 and their fourth in 12 years. Led by 25-game winner Hal Newhouser, the Tigers overcame a two-games-to-one deficit to win the 1945 World Series against the Chicago Cubs. Tobin made just one appearance in the fall classic, yielding two runs in three innings of relief in a 9-0 Game One drubbing in Detroit.

Tobin’s career in the big leagues came to an abrupt conclusion when the Tigers released him before spring training in 1946 after failing to find a trading partner. In parts of nine seasons, Abba Dabba posted a 105-112 record, completed 156 of 227 starts, and compiled a 3.44 ERA in 1,900 innings. He walloped 17 home runs and drove in 102 runs while batting .230.

After dividing the 1946 season with the Seattle Rainiers and the San Francisco Seals in the PCL, splitting 20 decisions as a swingman, Tobin hung up his spikes. “I never had the urge to stick around baseball after I was through as a player,” said Tobin, who almost held true to those words. He retired to Oakland, where he had spent the offseasons throughout his baseball career. He and his wife, Agnes (Caslin) Tobin, whom he met in Pittsburgh and married in September 1937, raised two daughters, Connie and Patricia.48 Tobin was coaxed out of retirement briefly to pitch for the Oaks in 1948 and 1949 (12 total appearances) and then again in 1950 by former batterymate Al Todd, who managed the Memphis Chickasaws. But it was obvious that Old Ironsides was no longer emotionally invested in the game. Tobin spent the remainder of his life working primarily as a barkeep and owned a tavern for six years.

Suffering from heart problems in his 50s, Tobin died at the age of 56 on May 19, 1969, at Providence Hospital in Oakland. He had suffered a heart attack following vascular surgery and was buried at the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Hayward, California.49

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Tobin’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record. Special thanks to Bill Mortell for his assistance with genealogical research.

Notes

1 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times. Tobin the Tantalizer,” New York Times, September 1, 1943: 31

2 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1936: 2.

3 “Minors Worth Watching,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1935: 5.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Dan Daniel, “Over the Fence,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1938: 4.

7 Dan Daniel, “From Second Flight to Flag Contender,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1945: 4.

8 Ibid.

9 Charles J. Doyle, “Traynor Calls for Pitch-Out on Number of Hurlers,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1937: 1.

10 Les Biederman, “Gooch’s Handling Real Story,” Pittsburgh Press, May 1, 1938: III, 1.

11 Charles J. Doyle, “Bucs Bids to Cards and Phils Revealed,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1938: 3.

12 “Tobin’s Hard Luck Ends in Brilliant Exhibition,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 25, 1938: 21.

13 United Press, “ ‘I’ll Show That McCarthy’ Tobin’s War Cry for Series,” Pittsburgh Press, September 22, 1938: 23.

14 Les Biederman, “Bucs Outlook Bright as Club Goes on Road,” Pittsburgh Press, July 10, 1939: 20.

15 Havey Boyle, “Mirrors of Sport,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 8, 1939: 16.

16 Though many fans were dismayed about the trade of Tobin, a bona-fide starting pitcher, for a swingman with a 20-25 record in parts of three seasons, Pittsburgh papers reported after the transaction that the Pirates had tried to move Tobin earlier. It had appeared that he would be demoted to Syracuse in the International League in partial payment for pitcher Johnny Gee before the deal for Lanning came through.

17 United Press, “‘I’ll Show That McCarthy.’”

18 Dan Daniel, “From Second Flight to Flag Contender.”

19 Associated Press, “Tobin Hurt as Nats Top Bees, 5 to 4,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 12, 1940: 18.

20 Howell Stevens, “Bees Looking More Like Ready Honey,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1940: 10.

21 Jack Malaney, “Braves Get Braver on Tobin’s Twirling,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1941: 5.

22 Howell Stevens, “Jim Tobin on Verge of Release Last Summer, Soared Back as Winning Moundster for Braves on His Butterfly Ball,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1941: 3.

23 Jack Malaney, “Braves Get Braver on Tobin’s Twirling.”

24 Howell Stevens, “Jim Tobin on Verge Of Release Last Summer.”

25 Daniel, “From Second Flight to Flag Contender.”

26 Herbert Goren (The Old Scout), “Tobin Defies Hitters With Knuckler,” New York Sun, May 15, 1942.

27 Frank C. True, “Freak Plays, Foolers for Fans, Toughest to Tag by Men in Blue,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1944: 9.

28 Arthur E. Patterson, “Tobin Limits Brooklyn to 4 Hits In 11 Innings, Then Errs Afield,” New York Herald-Tribune, April 23, 1942.

29 Howell Stevens, “Jim Tobin Slams Three Home Runs,” Boston Post, May 14, 1942: 16.

30 Fred Knight, “Probing Reveals Tobin, Lombardi on Home Run Diet,” Boston Traveler, May 14, 1945: 24.

31 Jerry Nason, “Tobin Hits 3 Homers, New Pitchers’ Mark,” Boston Globe, May 14, 1942: 1.

32 Irving Vaughan, “Tobin Blasts 3 Circuit Drives,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1942: 23.

33 Howell Stevens, “Al Javery Big Jive Man of Braves,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1942: 18.

34 Jack Malaney, “Junked Junket Just Another Jolt for Joe,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1943: 14.

35 Jack Malaney, “Jave Puts Jive Into Hub Fans With 1-Hitter,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1943: 14.

36 Harry Cross, “Boston Hands Hubbell First Loss of Year,” New York Herald-Tribune, June 27, 1943.

37 Jack Malaney, “Hurling Helps Braves When Batting Caves,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1943: 14.

38 Ken Smith, “ ‘Get Some Slowball Slickers,’ Ott’s Highball to Giants’ Scouts,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1944: 3.

39 Ed Rumill, “Tobin Great Pitcher for 90 Minutes,” Christian Science Monitor, April 28, 1944: 9.

40 Jerry Nason, “Tobin Hurls No-Hitter, Homers Against Brooklyn,” Boston Globe, April 28, 1944: 1.

41 Rumill, “Tobin Great Pitcher for 90 Minutes.”

42 Ibid.

43 Stan Baumgartner, “What’s Tobe Got That’s New? Merely Sidearm Knack of Slinging Knuckler,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 4, 1944.

44 Jack Malaney, “Sale of Tobin Shocks Boston,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1945: 14.

45 Dan Daniel, “From Second Flight to Flag Contender.”

46 Ibid.

47 Sam Greene, “Basement Boys Give Steve Two Big Dividends,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1945: 6.

48 Daily Courier (Connellsville, Pennsylvania), January 18, 1938: 15.

49 Jim Tobin’s Certificate of Death. Player’s file, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

James Anthony Tobin

Born

December 27, 1912 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

May 19, 1969 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.