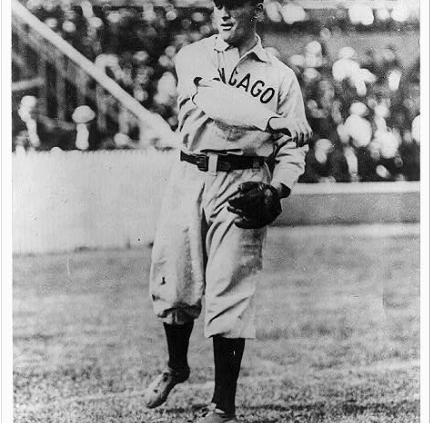

Jimmy Sheckard

In 1962 sportswriter Joe Reichler named Jimmy Sheckard as the left fielder on the All-Time Chicago Cubs team. Sheckard was a left-handed slugger who batted in the middle of the order during his early years with Brooklyn, then became a leadoff man and master at getting on base in his later years with the Cubs. In various seasons he led the National League in triples, home runs, slugging, runs, on-base percentage, walks, and stolen bases. Sheckard also was an outstanding defensive outfielder—both SABR and STATS, Inc., selected him to their retroactive Gold Glove teams for the first decade of the Deadball Era—and the right-handed thrower’s career assist total is one of the highest in history for an outfielder. One sportswriter described Sheckard as “a marvelous workman in his pasture and one of the surest, most deadly outfielders on fly balls that ever choked a near-triple to death by fleetness of foot and steadiness of eye and grip.” Another noted that he “did clever things in the outfield in nearly every game and was in a class by himself at trapping a ball.”

In 1962 sportswriter Joe Reichler named Jimmy Sheckard as the left fielder on the All-Time Chicago Cubs team. Sheckard was a left-handed slugger who batted in the middle of the order during his early years with Brooklyn, then became a leadoff man and master at getting on base in his later years with the Cubs. In various seasons he led the National League in triples, home runs, slugging, runs, on-base percentage, walks, and stolen bases. Sheckard also was an outstanding defensive outfielder—both SABR and STATS, Inc., selected him to their retroactive Gold Glove teams for the first decade of the Deadball Era—and the right-handed thrower’s career assist total is one of the highest in history for an outfielder. One sportswriter described Sheckard as “a marvelous workman in his pasture and one of the surest, most deadly outfielders on fly balls that ever choked a near-triple to death by fleetness of foot and steadiness of eye and grip.” Another noted that he “did clever things in the outfield in nearly every game and was in a class by himself at trapping a ball.”

“Sheckard was one of the brightest ball players in the business,” proclaimed teammate Johnny Evers, “and he was a bigger cog in the old invincible Cub machine than he ever received credit for being.” Many agreed. “Sheckard knows ‘inside baseball’ as well as the next man,” wrote one sportswriter, “and should be credited with some of the Chicagoisms that have heretofore been attributed to more famous members of the Cubs.” One reason he is less remembered than some Cub teammates is that, while he did many things brilliantly, he didn’t always do them consistently or at the same time. Sheckard’s highest batting average was .354 in 1901, but he also batted .239 in 1904 and .231 in 1908. He led the NL in 1903 with nine home runs, the same number he hit over the next six seasons combined. And his 147 bases on balls in 1911 were an NL record that stood until Eddie Stanky broke it in 1945, but in many other years his walk totals were about half that number.

One of the few men of Pennsylvania Dutch heritage to play in the major leagues, Samuel James Tilden Sheckard was born on November 23, 1878, in Upper Chanceford, York County, Pennsylvania. His full name reflected his father’s admiration for New York’s anticorruption governor Samuel Tilden, who lost one of the most controversial elections in American history two years before Jimmy was born. In 1888 the Sheckards moved across the Susquehanna River to Columbia in Lancaster County, where young Jimmy learned to play baseball. Six years later he got his first break when he filled in for an injured player on his hometown team and swatted a triple in a game against the Cuban Giants. In 1896 Sheckard pitched and played the outfield for four minor-league clubs, appearing in a combined 76 games and batting .310. With Brockton the following year he played mostly shortstop–against his wishes—and led the New England League with a .373 batting average and 53 stolen bases. The Brooklyn Bridegrooms acquired Sheckard toward the end of 1897, hoping that he would replace the aging Germany Smith, but he demonstrated that he was no shortstop by committing 19 errors in 11 games at the position.

As a left fielder in 1898, Sheckard hit .277 in 105 games for Brooklyn but was sent to the Baltimore Orioles after the season when new Bridegrooms manager Ned Hanlon brought outfielders Willie Keeler and Joe Kelley with him from Baltimore. The shuffling of the two clubs’ personnel benefited Sheckard. Given an opportunity to play nearly every day by Baltimore’s rookie manager, John McGraw, Jimmy batted .295, scored 104 runs, and led the NL with 77 steals. In the outfield he was second in the league in assists (33) and set the NL record for double plays by an outfielder (14). In 1900 Sheckard returned to Brooklyn and hit .300 as a backup to Keeler, Kelley, and Fielder Jones. When Jones jumped to the American League in 1901, Sheckard replaced him and became a star of the first order, leading the NL in slugging (.534) and triples (19), placing second in home runs (11) and total bases (296), and finishing third in hits (196) and RBIs (104) and fourth in batting average (.354). That September he became the first player of the 20th century to slug two grand slams in one season, hitting them in consecutive games.

But just as he appeared to be on the verge of greatness, Sheckard showed the first signs of the inconsistency that plagued him for most of his career. After jumping to the American League’s Baltimore Orioles for four games at the start of 1902, he changed his mind and returned to Brooklyn where his batting average dropped to .265. Sheckard bounced back with a .332 average in 1903, when he also led the league with nine home runs and tied Chicago’s Frank Chance for the stolen-base crown with 67, but the following season his hitting plummeted again, this time to a dismal .239. Even though Jimmy batted a respectable .292 in 1905, reports circulated that he wasn’t playing up to his potential or, worse yet, that he might even be washed up. Despite Sheckard’s popularity with the fans, on December 30, 1905, Brooklyn traded him to the Chicago Cubs for outfielders Jack McCarthy and Billy Maloney, third-baseman Doc Casey, pitcher Buttons Briggs, and $2,000. Initially Jimmy balked at the deal—the press speculated that he would have preferred a move to McGraw’s Giants—but eventually he had a change of heart and reported to the Cubs.

That transaction, along with the subsequent trade that brought Harry Steinfeldt to the Cubs, played an important part in tilting the balance of power in the National League from New York, where the Giants had won the two previous championships, westward to Chicago. Manager Frank Chance installed Sheckard in left field, moving Jimmy Slagle to center and shifting Frank Schulte to his natural position in right to complete the famous “S” outfield. Though he batted just .262, Jimmy established himself as a team leader who excelled at irritating the opposition—he had a “quiet way of getting a rival’s goat that has never been eclipsed,” noted one sportswriter. One example: Prior to the 1906 World Series he bragged that he would hit .400 against White Sox pitching. Sheckard then went 0 for 21 and failed to hit a ball out of the infield. McGraw blamed Jimmy’s embarrassing performance on Chance for playing the left-handed hitter against left-handed hurlers, against whom he sometimes struggled.

On June 2, 1908, Sheckard nearly lost the use of his left eye as a result of a fistfight with teammate Heinie Zimmerman. During the melee Jimmy threw something at the young infielder. Infuriated, Zimmerman picked up a bottle of ammonia and hurled it at his assailant. The bottle broke as it hit Sheckard between the eyes, spilling ammonia all over his face. Chance ran to Sheckard’s assistance but Zimmerman had the best of the manager, too, until the rest of the team intervened. The Cubs originally tried to cover up the incident, but Sheckard was sidelined for several weeks and the story eventually leaked. Jimmy batted a career-low .231 in just 115 games that season (his fewest since 1900) but returned in time to participate in the famous 1908 pennant race. With regard to the Fred Merkle incident, Sheck always claimed that his good friend Artie Hofman, the center fielder, should receive as much credit as second-baseman Johnny Evers because it was Hofman who alertly made the throw to Evers for the crucial forceout.

Thanks in large part to the writings of Ring Lardner, who was then a beat reporter covering the Cubs, Sheckard became well-known for his horseplay with Hofman and pitcher Lew Richie, with whom he formed three-quarters of a barbershop quartet (Jimmy sang baritone). The most famous example of his flakiness occurred in a game against Pittsburgh. After Pirate hitters had been spraying the ball all around him, a frustrated Sheckard stopped in the middle of left field, whirled several times, threw his glove up in the air, and went over to the spot where it landed. Orval Overall, pitching for the Cubs that day, couldn’t figure out why Sheckard was standing only a few feet from the left-field foul line and motioned for his outfielder to reposition himself. Sheckard refused. The next batter, Fred Clarke, hit a screaming line drive that went straight into Sheckard’s glove. Jimmy told teammates that the scheme changed his luck in the field from that day forward.

When there was talk after the 1910 season that the Cubs might trade Frank Schulte to the Phillies for John Titus, Schulte quipped that “they’d better pull it off quick if they want to keep me sane. It’s no cinch to play in that Cub outfield and stay in your right mind.” The trade never came off and both Schulte and Sheckard enjoyed banner seasons in 1911. As the Cubs leadoff hitter, Sheckard led the NL in runs (121) and bases on balls (a record 147). “Sheckard is not built according to approved models of men hard to pitch to,” wrote one reporter. Officially (though inaccurately) listed at 5’9″ and 175 lbs., Jimmy was “no midget,” according to the reporter, “but when it comes to judging a ball to a hair line and outguessing pitchers, he is there, as his base on balls record shows.” The reporter described Sheckard at this stage of his career as “positively fat,” but his girth was no handicap “to a man who walks to base in preference to doing the Cobb stunt.”

Against Cincinnati on April 20, 1912, Sheckard almost pulled a “Merkle” himself after hitting a 10th-inning home run off George Suggs. As he hit the ball, Jimmy said later, he remembered he had dropped his glove in left field after the Reds made the third out in the top half of the inning. During his home-run trot, Sheckard cut across the field after touching second, retrieved his glove, and suddenly remembered that his run wouldn’t count unless he completed the circuit. With his teammates screaming, he went back to touch third and home. As Sheck tallied the winning run, plate-umpire Bill Brennan said, “I was waiting for you, Jimmy.” (Coincidently, the Cincinnati manager that day was Hank O’Day, who was the umpire when Fred Merkle failed to touch second base in 1908.) Though he led the NL in walks again with 122, and his .392 on-base percentage was 52 points above the NL average, Sheckard batted just .245 in 1912. In an era obsessed with batting average, that made him expendable.

In April 1913 the Cubs sold the 34-year-old Sheckard to the St. Louis Cardinals. He batted just .199 in 52 games, so the Cardinals placed him on waivers in July and he spent the rest of the season with the Cincinnati Reds, for whom he batted .190 in 47 games. It was the final stop in his 17-year career in the major leagues. Despite an offer to join the Federal League in 1914, Sheckard remained in Organized Baseball with Cleveland of the American Association. In the spring of 1917 Sheckard played with independent teams in Brooklyn before returning to Chicago and serving as a coach for the Cubs. During World War I he served as athletic director at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, which sponsored 48 baseball teams with more than 2,000 players.

After the war Sheckard went home to Columbia, Pennsylvania, where he managed semipro ball. He discovered shortstop Les Bell, a Harrisburg native who later played for the Cardinals, Braves, and Cubs. “Jimmy was a fine man,” Bell told researcher Greg Dubbs. “Very fundamental. Bunt, hit and run, stolen base, defense—the way he played the game from, what I’ve been told.” Sheckard remained a character. “As a manager he wore white socks and a white shirt and was always chewing tobacco,” Bell remembered. “He’d hitch his pants at the knees, sit himself down and spit away. Funniest damn thing I ever saw—by the end of a game those white socks were always a very distinctly brownish color.”

Sheckard eventually became the baseball coach at Franklin & Marshall College and managed the Lancaster Red Roses during their one season in the Class D Interstate League in 1932. In the mid-’30s he declined an offer from Connie Mack to manage Federalsburg of the Eastern Shore League, a decision he later regretted. By the end of the decade Sheckard was down on his luck. Having lost his modest savings in the 1929 stock-market crash, he rose each morning to drive a truck on a four-hour trip collecting 10-gallon, 100-lb. milk cans from farmers in the Lancaster area.

On a cold Sunday in January 1947, Jimmy Sheckard walked to his attendant’s job at a gas station directly across from Stumpf Field, the home of the Red Roses. As he limped toward the station (he suffered from arthritis in his left foot, which doctors believed was the result of an old baseball injury), a car struck him from behind and knocked him to the ground. Sheckard died of head injuries three days later. Umpire Bill Klem, who had called the balls and strikes in many of Jimmy’s games in the National League, presided over a ceremony in his honor at Stumpf Field, and the city of Lancaster erected a monument to his memory in Buchanan Park.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Samuel James Tilden Sheckard

Born

November 23, 1878 at Upper Chanceford, PA (USA)

Died

January 15, 1947 at Lancaster, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.